Stephen Toulmin

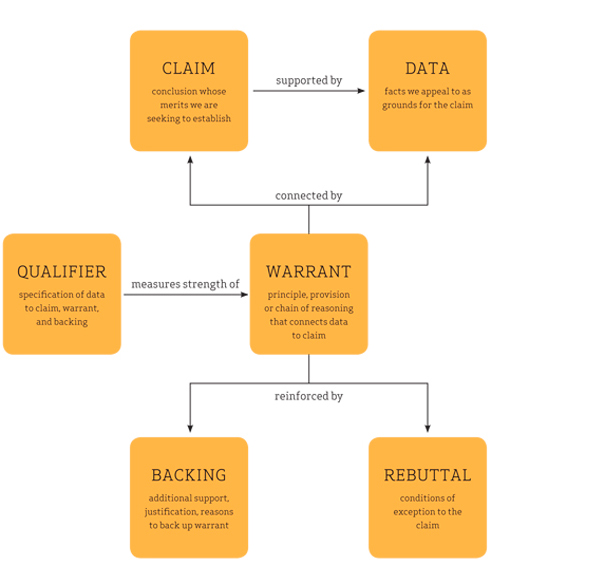

Stephen Toulmin was a British philosopher, author, and educator. Influenced by Ludwig Wittgenstein, Toulmin devoted his works to the analysis of moral reasoning. Throughout his writings, he sought to develop practical arguments which can be used effectively in evaluating the ethics behind moral issues. His works were later found useful in the field of rhetoric for analyzing arguments. The Toulmin Model of Argumentation, a diagram containing six interrelated components used for analyzing arguments, was considered his most influential work, particularly in the field of rhetoric and communication, and computer science.

The Toulmin Model

- Claim: the position or claim being argued for; the conclusion of the argument.

- Grounds/Data: reasons or supporting evidence that bolster the claim.

- Warrant: the principle, provision, or chain of reasoning that connects the grounds/reason to the claim.

- Backing: support, justification, reasons to back up the warrant.

- Rebuttal/Reservation: exceptions to the claim; description and rebuttal of counter-examples and counter-arguments.

- Qualification: specification of limits to the claim, warrant, and backing. The degree of conditionality asserted

Claim

A claim is a statement that you are asking the other person to accept. This includes information you are asking them to accept as true or actions you want them to accept and enact.

The six most common types of claims are fact, definition, value, cause, comparison, and policy.

- A claim of fact takes a position on questions like: What happened? Is it true? Does it exist? Example: “Though student demonstrations may be less evident than they were in the 1960s, students are more politically active than ever.”

- A claim of definition takes a position on questions like: What is it? How should it be classified or interpreted? How does its usual meaning change in a particular context? Example: “By examining what it means to ‘network,’ it’s clear that social networking sites encourage not networking but something else entirely.”

- A claim of value takes a position on questions like: Is it good or bad? Of what worth is it? Is it moral or immoral? Who thinks so? What do those people value? What values or criteria should I use to determine how good or bad? Example: “Video games are a valuable addition to modern education.”

- A claim of cause takes a position on questions like: What caused it? Why did it happen? Where did it come from? What are the effects? What probably will be the results on a short-term and long-term basis? Example: “By seeking to replicate the experience of reading physical books, new hardware and software actually will lead to an appreciation of printed and bound texts for years to come.”

- A claim of comparison takes a position on questions like: What can be learned by comparing one subject to another? What is the worth of one thing compared to another? How can we better understand one thing by looking at another? Example: “The varied policies of the US and British education systems reveal a difference in values.”

- A claim of policy takes a position on questions like: What should we do? How should we act? What should be future policy? How can we solve this problem? What course of action should we pursue? Example: “Sex education should be part of the public school curriculum.”[3]

Many people start with a claim, but then find that it is challenged. If you just ask me to do something, I will not simply agree with what you want. I will ask why I should agree with you. I will ask you to prove your claim. This is where grounds become important.

Grounds/Data

The grounds (or data) is the basis of real persuasion and is made up of data and hard facts, plus the reasoning behind the claim. It is the ‘truth’ on which the claim is based. Grounds may also include proof of expertise and the basic premises on which the rest of the argument is built.

The actual truth of the data may be less than 100%, as much data are ultimately based on perception. We assume what we measure is true, but there may be problems in this measurement, ranging from a faulty measurement instrument to biased sampling.

It is critical to the argument that the grounds are not challenged because, if they are, they may become a claim, which you will need to prove with even deeper information and further argument.

Information is usually a very powerful element of persuasion, although it does affect people differently. Those who are dogmatic, logical, or rational are more likely to be persuaded by factual data. Those who argue emotionally and who are highly invested in their own position will challenge it or otherwise try to ignore it. It is often a useful test to give something factual to the other person that disproves their argument and watch how they handle it. Some will accept it without question. Some will dismiss it out of hand. Others will dig deeper, requiring more explanation. This is where the warrant comes into its own.

Warrant

A warrant links data and other grounds to a claim, legitimizing the claim by showing the grounds to be relevant. The warrant may be explicit or unspoken and implicit. It answers the question ‘Why does that data mean your claim is true?’

The warrant may be simple and it may also be a longer argument, with additional sub-elements including those described below.

In many arguments, warrants are often implicit and hence unstated. This gives space for the other person to question and expose the warrant, perhaps to show it is weak or unfounded.

Backing

The backing (or support) for an argument gives additional support to the warrant by answering different questions.

Qualifier

The qualifier (or modal qualifier) indicates the strength of the leap from the data to the warrant and may limit how universally the claim applies. They include words such as ‘most’, ‘usually’, ‘always’ or ‘sometimes’. Arguments may hence range from strong assertions to generally quite floppy with vague and often rather uncertain kinds of statements.

Another variant is the reservation, which may give the possibility of the claim being incorrect.

Rebuttal

Despite the careful construction of the argument, there may still be counter-arguments that can be used. These may be rebutted either through continued dialogue or by pre-empting the counter-argument by giving the rebuttal during the initial presentation of the argument.

Any rebuttal is an argument in itself and thus may include a claim, warrant, backing, and so on. It also, of course, can have a rebuttal. Thus if you are presenting an argument, you can seek to understand both possible rebuttals and also rebuttals to the rebuttals.