14: Shadows of the Bat: Constructions of Good and Evil in the Batman Movies of Tim Burton and Christopher Nolan (Born)

Sarah Wangler and Tina Ulrich

By Simon Philipp Born

Abstract

The superhero narrative is typically premised on the conflict between the hero and the villain, the mythical struggle between good and evil. It therefore promotes Manichaean worldview where good and evil are clearly distinguishable quantities . This bipolar model is questioned in the Batman movies of Tim Burton and Christopher Nolan. Since his creation in 1939, Batman has blurred the line between black and white unlike any other classic comic book superhero . As a “floating signifier”, he symbolizes the permeability of boundaries, for his liminal character inhabits a world between light and darkness, order and anarchy, hero and villain. Drawing on the complex ambiguity of the character, Tim Burton and Christopher Nolan deconstruct the traditional dichotomy of good and evil in the superhero narrative by reversing its polarity and emphasizing the fictionality of it all. Although they differ in style and method , both filmmakers invite us to overcome the Manichaean belief in favor of a more ambivalent and sophisticated viewpoint.

Keywords

Batman, good and evil, Manichaeism, duality, superhero, mythology theatricality

The 21st century is proving to be the Golden Age of superhero movies. Comic book stories about superhuman beings fighting evil, which have circulated in popular culture since the 1930s, are now being recognized and consumed by an even broader audience. the omnipresence of the superhero transforms him from pop-cultural icon into modern-day myth. Drawing on Joseph Campbell’s works, David Reynolds remarks that modern myths like the superhero narratives are not confined to religious ideologies, but rather “develop from ethical perspectives as they relate to a political and economic world”.2 Indeed, their stories about heroism, justice, virtue and villainy not only entertain us, but also function as a moral educator, reinforcing Western values and mediating norms of social behavior: “Superhero stories bill themselves as tales of courage and friendship, representing American ideals at their best while attempting to pass on a strong moral code to the impressionable children who read comic books, play superhero video games, and watch superhero films.”3 In order to explain these stories’ widespread popularity, scholars like Richard J. Gray and Betty Kaklamanidou have argued that superhero narratives respond to the general longing for “true heroism” and a clear distinction between right and wrong in an uncertain and morally ambiguous globalized world: “Superhero films promote the ideas of peace, safety and freedom and seek to restore the planet to a nostalgic harmony.”4

To promote these ideals, the superhero narrative is typically premised on the conflict between hero and villain, the mythical struggle between good and evil. In the superhero genre, good and evil mainly fulfill narrative functions. The struggle between hero and villain produces suspense and drives the plot, where, ironically, the roles of protagonist and antagonist are switched: the villain, and not the hero, plays the active part, as his evil actions initiate the story and call upon the hero to act. According to Richard Reynolds, “The common outcome, as far as the structure of the plot is concerned, is that the villains are concerned with change and the heroes with the maintenance of the status quo.”5 The evil antagonist is a necessary counterforce who challenges the pro- tagonist and allows him to be good. the rise and fall of the villain is a socially required evaluation that crime does not pay, while the certain triumph of the hero reminds the audience of the superiority of the values he represents. As far as the narrative structure of the superhero story and the ideology it conveys are concerned, good and evil are mutually dependent, one cannot exist without the other. The threat from the villain forces the hero to act, his malignity enabling the hero to show off his goodness. Superhero mythologies therefore seem to promote a Manichaean worldview. Recalling the dualistic cosmology of the late-antique prophet Mani, life is conceived as a constant struggle between two external forces – the spiritual realm of light and the material realm of darkness. In a yin-and-yang balance of opposites, the existence of one is defined through the existence of the other.

This bipolar explanation of the world is questioned by the more ambivalent take of contemporary superhero films, as Johannes Schlegel and Frank Habermann remark. Postmodern films like Unbreakable (M. Night Shyamalan, US 2000) or Hellboy (Guillermo del Toro, US 2004) display in their “metanarrative”6 deep distrust of the absolute distinction between good and evil, which they expose as constructions rather than natural quantities: “The dichotomy of good and evil in contemporary superhero films is first and foremost negotiated, performatively generated and constantly debated, rendering it an unstable phenomenon of produced and ascribed meaning that has to be reaffirmed perpetually”.7 This essay argues that good and evil are socially constructed categories that regulate the world and explain human behavior. Their order-obtaining duality is culturally mediated in narratives and visual texts such as superhero stories. Ultimately, some of these texts not only reflect but also disclose and willingly subvert the clear-cut dichotomy in favor of a more complex and sophisticated viewpoint, as is the case with the Batman movies of Tim Burton and Christopher Nolan. Their visions of the Caped Crusader are unique, yet not completely out of line with the character. Instead, they ingeniously condense Batman’s conflicting history into a multi-layered psychologization. In his many incarnations, Batman blurs the line between black and white, and unlike any other classic comic book superhero he constructs a world of multitudinous grey. Long before the postmodern hero deconstructions found in graphic novels like Alan Moore’s Watchmen (U.S. 1986–87), he had already been conceived in his original draft as an alteration and revision to the superhero myth. The Dark Knight is driven by his dual nature. in order to defend the light, he utilizes his darkness to fight evil (see fig. 1). Additionally, his fragmented textual existence self-consciously reflects his symbolic nature, unveiling the fictionality and theatricality of his character.

The floating signifier

Since his debut in Issue 27 of Detective Comics, from May 1939, Batman has become one of the most popular and most iconic comic book superheroes of all time, spawning a gigantic media franchise that includes major blockbuster films, TV shows, video games, direct-to-video animations, comic books, novels and a massive range of licensed merchandise. All these simultaneously existing Batmen challenge our traditional notion of a fictional character as coherent, semantic figure. Who is the “real” Batman? The original comic book vigilante from the 1940s, Adam West’s colorful “Camped Crusader” from the infamous Batman TV show (ABC, US 1966–1968), the dark and gritty incarnation of the 1980s, Christian Bale’s post–9/11 Dark Knight or even the Lego Batman? The answer is that he is all of them. Batman is the sum of all his iterations, a hypertext that connects conflicting identities, media texts and storyworlds in an interacting matrix. According to Roberta Pearson and William Uricchio, Batman is a “floating signifier”, not defined by any sort of author, medium, time period or primary text, but held together by a small number of essential character traits such as his iconographically specific costume, his secret identity as billionaire Bruce Wayne, the murder of his parents, his setting (Gotham City) and a recurring cast of friends and foes.8 For Will Brooker, even these core components can be reduced to one essential element as the minimal marker for a Batman story – the Bat logo, Batman’s symbol of his crime-fighting idea, which also functions as his unique brand both inside and outside the narrative (see fig. 2).9

Similarly to Brooker, Paul Levitz ponders the idea that Batman’s protean nature is “built on a purely visual icon, which has proved to be remarkably reinterpretable”.10 He refers to the fact that Batman’s character originated as loose sketch of a bat-man figure inspired by Leonardo da Vinci’s drawings of a flying machine. When comic artist Bob Kane and author Bill Finger introduced the Caped Crusader in 1939, he was conceived as a quick-fire response that would capture the huge success of Superman, who had debuted just a year before. His character was not yet fully drawn, as demonstrated by the fact that his defining origin story was only told six months later. Kane and Finger combined various tropes and figures of popular culture of the 1930s present in movies, pulp fiction, comic strips and newspaper headlines and formed them into one,11 but Batman is primarily influenced by the detective stories of his time, like most of the comic book superheroes. Drawing on their roots in crime and mystery fiction, detective stories also contain a Manichaean philosophy. According to Marcel Danesi, they transfer the medieval struggle between angels and demons into the secular contexts of investigators and perpetrators: “The detective story is, in a sense, a modern-day morality play. Evil must be exposed and conquered. In the medieval period the evil monster or demon was vanquished by spiritual forces, such as Goodness; today, he is vanquished by a detective or a superhero crime fighter.”12 Batman varies the tradition of the detective story, as he is both angel and demon in one person. In terms of mythology, he combines two major mythical archetypes, namely the Hero and the Shadow.13

Batman is a superhero, but a very human one. He has no special powers; he was not born on an alien planet and bitten by a radioactive insect. He relies purely on his limitless resources: a multi-billion dollar heritage, outstanding combat skills, an inventive mind and, of course, his qualities as “world’s greatest detective”, which relate him to other famous crime-solving characters from literature like Sherlock Holmes or pulp hero Doc Savage. Batman accords perfectly with Joseph Campbell’s famous definition of the hero as “someone who has given his or her life to something bigger than oneself”.14 Batman is not driven, however, by a noble impulse to altruism like Superman, but rather by the experience of loss and a need for vengeance.15 Having been unable to prevent the murder of his parents, he finds the only way to halt injustice is through his second life, as masked vigilante. But even when as new and empowered Caped Crusader he becomes painfully aware of the limits of his might, he cannot prevent either himself or those entrusted to him from getting hurt. In his masquerade, Batman does not overcome his trauma, but instead relives it anew night by night. There is an inherent darkness to the character and his setting. Newer comic books like Frank Miller’s The Dark Knight Returns (1986) psychologize Batman as broken justice fanatic, a dark reflection of the bright Superman, the American Dream degenerated into a nightmare. He shares similarities with the Jungian archetype of the shadow, the presentation of the psyche’s dark, hidden side, which is not necessarily evil, but rather everything the self wants to conceal and keep out of the light.16 Batman is not a savior, but an avenger. A creature of the night, a mystery figure dressed in black who employs his darkness to mercilessly fight crime like his pulp predecessor the Shadow. His blackness condenses in the image of a bat, a central symbol in the American Gothic tradition of the late 19th and early 20th centuries that conjured up “images of darkness, terror, animal savagery, and soul-sapping vampirism, all of which were often linked to notions of ethnic infiltration”.17 Like the infamous title character of Bram Stoker’s Dracula (1897), Batman operates in the shadows, flies through the night and radiates an intriguing aura of awe and terror. Bela Lugosi’s iconic portrayal of the prince of darkness in Tod Browning’s Dracula (US 1931) may even have inspired Batman’s cape – just as the mystery film The Bat Whispers (Roland West, US 1930), where a masked murderer named “the Bat” terrorizes America’s upper class, features a prototype of the Bat logo.

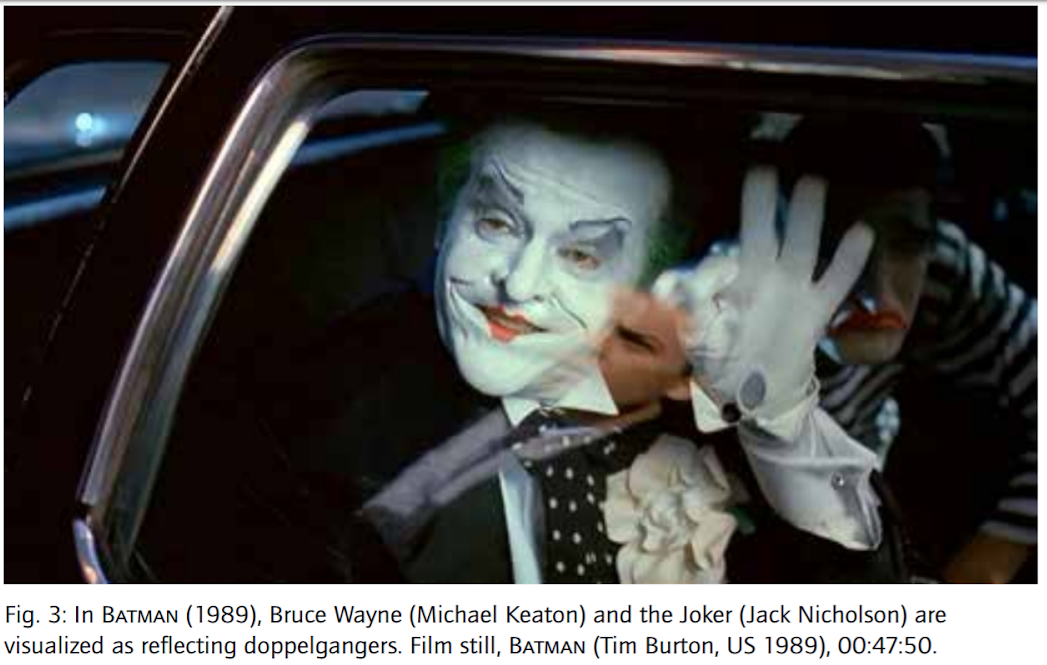

In conclusion, Batman’s character has origins not only in heroic figures like Sherlock Holmes, but also in famous incarnations of evil like Dracula. This vital duality is also evident in Batman’s relationship with his enemies, who function as his doppelgangers: “Understanding Batman requires us to look hardest at him and his foes. The villains mirror and warp his darkness, his fears, his needs for puzzles to solve and criminals to hurt, and his hopes too.”18 Batman’s antagonists play a part for the narrative that is as important as the part played by the protagonist himself. Just as the Dark Knight is not solely good, his opponents are not solely evil. Batman’s rogues’ gallery unfolds as a panorama of tragic existences that were shattered by reality. In a dystopian hell like Gotham City, “All it takes is one bad day to reduce the sanest man alive to lunacy”, as the Joker explains in Alan Moore’s graphic novel The Killing Joke (1988).19 The comic also raises the question whether Gotham’s villains created Batman as their own nemesis, or if the self-appointed avenger attracted these troubled spirits by his presence, thus being himself responsible for their making. “I made you, you made me first”, Batman growls at his eternal adversary, the Joker, at the end of Batman (1989).20 “You complete me” is the clown’s answer 19 years later in The Dark Knight (Christopher Nolan, US 2008).21 Batman and his villains are “locked into a ritualized dance” with each other (see fig. 3), justifying each other’s existence.22 Both sides adopt costumed identities in attempts to make sense of life.23 The carnivalesque world of Batman is a stage where the Manichean struggle between good and evil is nothing but a role-play acted out by the Dark Knight and his foes.

This celebration of theatricality where the mask is of the utmost importance can be seen most notably in the movie adaptations of Tim Burton and Christopher Nolan. With the examples of Batman Returns (1992) and The Dark Knight (2008), I shall demonstrate that Burton and Nolan can be seen as opposing poles on the same scale. Both are heavily influenced by film noir, but while Burton experiments with the fantastic-melodramatic component of the epochal film style on the edge to expressive gothic horror, Nolan courts a contemporary update in the tradition of the neo noir. Above all, Batman Returns (1992) and The Dark Knight (2008) deconstruct the dichotomy of good and evil in the superhero narrative by reversing its polarity and emphasizing the artificiality of it all.

Batman Returns or the insurrection of signs

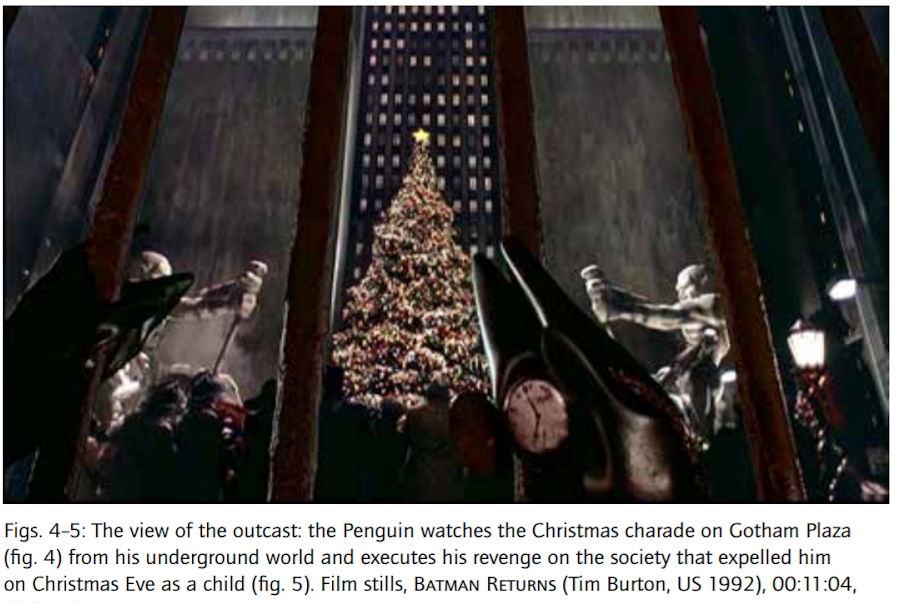

Christmas in Gotham City – a never-ending nightmare. Flanked by two absurdly large muscular statues, a gigantic Christmas tree lights the overcrowded Gotham Plaza. An allegory of power. The Christmas tree sits between the sign codes of fascist architecture as a central image of mass slavery, the tyranny of department stores and advertised dreams. The city is run by tycoon Max Shreck (Christopher Walken), whose very name hints at his bloodsucking nature – actor Max Schreck played the title character of the silent horror film Nosferatu, Eine Symphonie des Grauens (Nosferatu – A Symphony of Horror, Friedrich Wilhelm Murnau, De 1922). The ubiquitous symbol of Shreck’s store empire is the face of a grinning cartoon cat reminiscent of Felix the Cat. Through the im- age of a powerful corporation hiding behind the friendly face of a cartoon animal, Burton processes his time as a subordinate at the Walt Disney Company, which has always dominated the American popular culture with its many images, conservative ideologies and merchandise products. Suddenly, a big present box arrives at the Plaza and unleashes a cascade of maniac circus clowns with machine guns. The scenery descends into chaos as bikers with enormous skulls trash hot-dog stands, a devilish fire breather incinerates teddy bears and a maniac ringleader shoots the Christmas tree to pieces with his barrel-organ Gatling gun. An insurrection of signs, released by the bizarre Penguin (Danny DeVito) who lives in Gotham’s sewers. Flushed away as a deformed baby of rich parents on Christmas Eve twenty years ago, Penguin takes revenge on the affluent consumer society that rejected him as a monster (see fig. 4–5). He kidnaps Shreck and blackmails him into assisting his ascent into the world above, recycling Shreck’s dirty secrets that have washed up in his underground kingdom and using them against him. from toxic waste to body parts – the by-products of a ruthless capitalism.

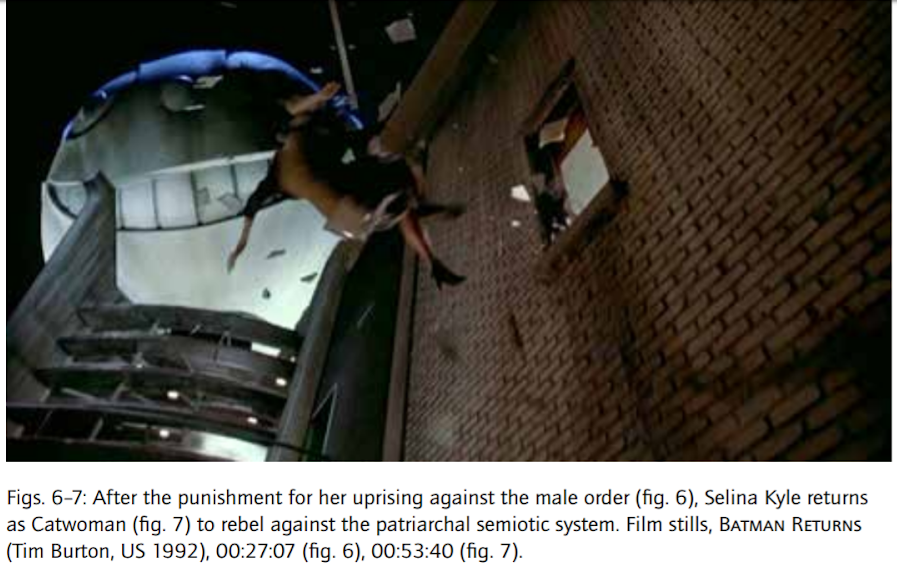

Society creates its own demons. Even the whip-wielding Catwoman is a product of a sexist macho society that keeps its women small as tamed pussycats. And, if an unruly female does not obey the male order, she is pushed out of the window, as happens to secretary Selina Kyle (Michelle Pfeiffer), who is killed by her boss, Max Shreck, for her curiosity (see fig. 6). Down in the gutter, however, Selina is resurrected with the help of wild stray cats. The tables are turned: from being a helpless mouse that had to be

rescued by Batman from bad guys in an earlier scene, Selina transforms into a black beast and now has claws of her own: “I am Catwoman. hear me roar!”24 For her empowerment against a chauvinistic busiuness world she adapts the symbol of her oppression – the cat – and reframes it (see fig. 7). The grinning cat turns into a furious panther that lives out its sexual autonomy in its animalistic ferocity in the spirit of Jacques Tourneur’s Cat People (US 1942).25 Selina destroys her stuffy apartment, which is filled with the slavish insignia of her old life, and tailors the skin of her new identity – a skintight, black-leather outfit whose seams remain all too visible. The emphasis on the fragmented self refers to the construction and performance of gender roles; as a pop-cultural condensation of post-feminist theories, Catwoman reveals the correlation between sexuality, power and identity. Her rebellion against masculine rule is doomed to failure, however, as Catwoman is killed again and again throughout the movie by every male protagonist. Even though she exposes on the screen the uneven power relationship between men and women, she cannot change it. Located between the poles of fetishized male fantasy and a feminist avenger model, Selina’s self-search reaches an impasse. Objectified by the male’s gaze, her riot is smashed by Hollywood’s patriarchal semiotic system.26

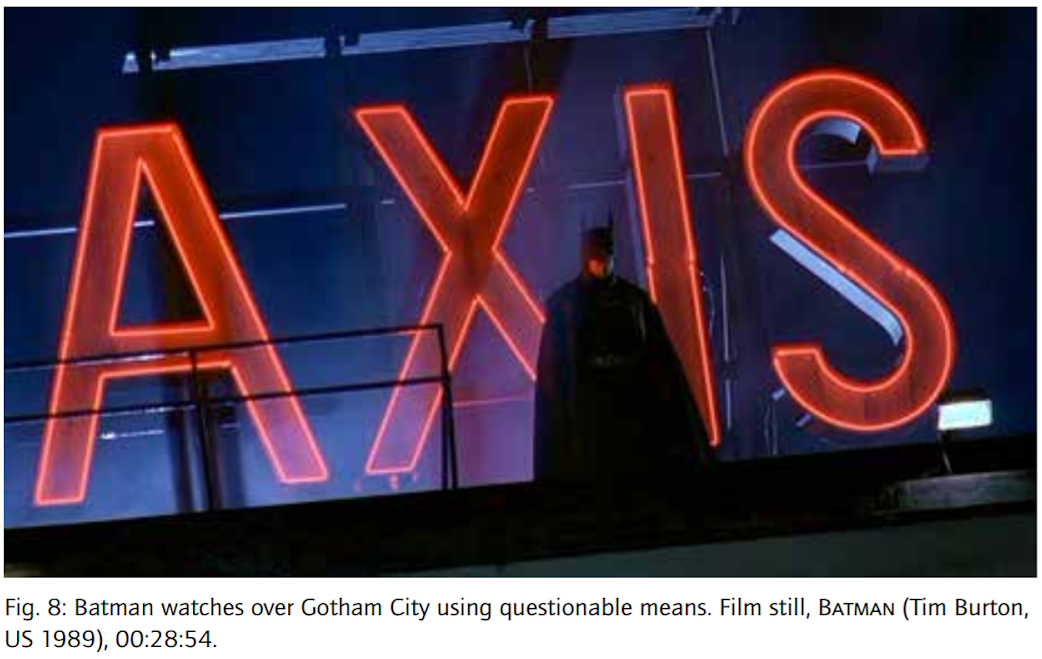

While the Penguin and Catwoman reign over Gotham’s streets with terror, another beast man is fielded to restore the order: Batman (Michael Keaton). Batman, too, has been maimed by the outside world and left with emotional scars, but his revenge is directed not at the causes of his pain, but at its symptoms – the criminals. He fights the freaks and monsters of the town, with whom he has more in common than with the sane citizens he swore to protect. Burton draws the disrupted psyche of the Dark Knight as a hopeless case of a traumatized individual who has lost his own identity within the whole superhero masquerade. Batman is no longer the mask of Bruce Wayne; Bruce Wayne is the mask of Batman. Burton’s Batman is a deeply introverted character, trapped within his inner trauma. He puts on the mask of the monstrous in order to shield himself from the outside world. He does not even flinch from killing, but takes lives with a casualness and malice that make you shudder. First he scorches the fire breather with his Batmobile, then he slips a strong thug a bomb and sends him to hell with a diabolical smile. Is Batman a gruesome sadist? There is a revealing shot in Burton’s first Batman movie where the protagonist looks down from the roof of the Axis Chemicals factory, with “Axis” in big letters shining above his dark figure (see fig. 8). While Batman fought bravely against the Axis powers in a propagandistic movie serial from 1943, he now

seems to adapt their relentless methods to control Gotham City as in a fascist

surveillance state.27 This sinister interpretation does not move far from Frank Miller’s version of the Dark Knight.

“I guess I am tired of wearing masks.”28 In Batman Returns (1992), good and evil appear not as fixed, moral quantities, but as narrative constructs whose compositions are freely variable. They are attributions, masks, in which one appears before others and which others attach to one. They mean protection (Batman), but also freedom (Catwoman). The perpetual role-play goes on until the mask becomes the skin and the skin a mask. After a short liaison, Bruce Wayne and Selina Kyle meet again at a

masquerade ball, no disguises needed. In a dance of mask and identity, they recognize each other’s second face by means of a line of dialogue they had shared as their alter egos (see fig. 9–10). They see the mask behind the face and ask, “Does this mean we have to start fighting?”29 The advanced schizophrenia of their dual identities prevents

the reconciliation of their personalities both with themselves and with the other. The masquerade theme in Batman Returns (1992) becomes a game of signs. As in his other movies, Burton reinterprets established sign codes: black becomes white, and ugly is beautiful. Christmas, a leitmotif of the movie, is unmasked as commercial mass deception.30 The perversion of Christmas suggests the protagonist’s lost innocence: too often the violence is aimed at tokens of infantility and cuteness or stems directly from

them – as in the case of Batman’s gadget toys and Penguin’s obscure weaponry. The destruction of anything “that appears benign, cute or cuddly” even led bewildered Batman-chronicler Mark S. Reinhart to the conclusion that Burton hatches a distaste for “just about anything that society at large would perceive as ‘good.’”31

In the end, the concepts of good and evil or normal and abnormal are just a matter of perception. Arguably the only purely evil character in the movie is the human Max Shreck, who behind a façade of normalcy manipulates, corrupts and kills. As for the other freaks and monsters, Burton sees them not as villains, but as victimized individuals.32 He breaks through the common association of disability with evil in fiction,33

As his variation on the Obsessive Avenger–stereotype, a character who relentlessly pursues those he holds responsible for his disablement, is rendered as a misunderstood monster and applied to villains and heroes alike. As in most of Burton’s work, in a Burton movie you fear not the Other but the “ordinary”. In the end, Batman Returns (1992) is sheer gothic, modeled after the cinematic re-imaginings of classic gothic tales. Burton eagerly draws on the vast symbolic-image stock of the horror movie, influenced by German expressionism (see fig. 11–16). In the tradition of films like Das Cabinet des Dr. Caligari (The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari, Robert Wiene, DE 1920), he uses stylized settings to illustrate the dark and twisted world of his film. Burton externalizes the protagonist’s ambivalent psychic states in an opulent pictorial design. the repressed subconscious of the characters turns outward in the bizarre exaggerations and expressive color contrasts of the set design, the gloomy lighting, the costumes, the make-up and the sinister score by composer Danny Elfman. The characters’ environments are framed as psychological dioramas that strung together would evoke the image of a multi-faceted theme park. Burton’s Gotham is a world of décors in which no neutral space exists, no outside, no escape. A postmodern no man’s land in which the signs of light and darkness, reason and madness, reality and fiction are perverted into their eerie opposites.

A taste of theatricality: The Dark Knight

Burton’s Batman vision is dark, fatalistic, oppressive. the Dark Knight loves his shadowy existence so much that he refuses to stand in the light of attention. the proactive villains take over and marginalize the hero in his own movie. By contrast, in Batman Begins (2005) Christopher Nolan resets the Caped Crusader as the main protagonist of the story and explores the beginnings of the character. After Joel Schumacher’s gaudy and flamboyant take in Batman Forever (US 1995) and Batman & Robin (US 1997), which did not resonate well with fans and critics, Nolan seeks to wipe the slate clean with his elaborate reboot of the character. Basically he brings the superhero “down to earth” and connects him with the contemporary American zeitgeist (see fig. 17). For that, he stepped outside the studio and shot on-location in major cities like Chicago and London (Batman Begins, 2005; The Dark Knight, 2008) and Los Angeles, New York and Pittsburgh (The Dark Knight Rises, US 2012) in order to compose a hyper-real cityscape of Gotham City. Following the films’ courted authenticity and realism, Batman’s world is purged of any supernatural, fantastic and whimsical elements that could expose its comic book source material. Instead, Nolan focuses in his first Batman movie on the Dark Knight’s character development as he struggles to adopt a moral position in a corrupted society. The battle between good and evil is portrayed as a dispute between opposing principles, ideas and philosophies. Batman’s ethical code, which requires him to work outside the law but never to kill, stems from the dialectic juxtaposition of his father figures: from the thesis of empathetic understanding embodied by his murdered father Thomas Wayne (Linus Roache) and carried further by his butler Alfred (Michael Caine) and the antithesis of absolute and revengeful justice claimed by his fundamentalist mentor Ducard/Ra’s al Ghul (Liam Neeson) comes the synthesis of the principled avenger Batman (Christian Bale).

After 135 minutes of soul-searching in Batman Begins (2005), the masked vigilante is finally ready to face his equal – the Joker (Heath Ledger). At the end of the film, Lieutenant Gordon (Gary Oldman) has already established a connection between the two on the basis of their staged appearance. Gordon talks about escalation and how Batman’s advent might encourage a new type of criminal. He hands the Dark Knight a joker card with the words, “You’re wearing a mask, jumping off rooftops. Now, take this guy. Armed robbery, double homicide. Has a taste for the theatrical, like you.”34 Consequently, The Dark Knight (2008) opens with the introduction of the Joker. the prologue of the film shows a group of clown-masked gangsters robbing a mob bank while talking about their anonymous boss, the Joker. their heist successful, they start to kill each other off in order to increase the share each will receive, until only one robber is left. Before he leaves with all the money, this last robber lifts his clown mask in an extreme close-up, revealing not his hidden identity, but another mask: the scarred and painted face of the Joker. the ambiguous masquerade of the prologue confirms Gordon’s fears – the Joker is established as a direct consequence of Batman’s theatricality. The Joker’s “mask” dissolves the analogy between face and identity, for his “makeup does not hide his true identity, but instead attests to the absence of one”,35 making him a being of pure theatricality, a displayed sign of a sign (see fig. 18).36

In keeping with the film’s main preoccupation with duality, the Joker is depicted not only as Batman’s criminal equivalent but also as the ultimate counterforce who answers Batman’s desire for order with chaos.37 Their combat represents the constant struggle Batman has to face as outlaw vigilante: “Batman emerges as a hero positioned in the darkness between extremes, mediating between the oppressive power of modern systems and the chaos of postmodern anarchy”.38 In view of the increasing number of victims and the experience of powerlessness in his staged no-win scenarios, the battle against the Joker becomes a crucial test for the good. How can such boundless evil be countered? Nolan’s Dark Knight trilogy is heavily influenced by the terror attacks of 9/11 and their aftermath. His Gotham City becomes a stage for America’s current anxieties, with the audience compelled to connect their own experiences of 11 September with the experiences of the film,39 above all in the confrontation with a faceless evil with which there can be no negotiation and which cannot be dealt with: “You have nothing, nothing to threaten me with. Nothing to do with all your strength”, the Joker replies to the hard and desperate blows of the Dark Knight.40 The interrogation scene between the two in Gordon’s Police Department is a key scene of the film: under the eye of the law, Batman temporarily oversteps his limits and tortures the Joker in order to get information about the whereabouts of his two hostages in a literal ticking-bomb scenario (see fig. 19). In order to beat the Joker, Batman creates an emergency situation, mirroring the extreme measures taken by the Bush administration in the War on terror, with his pure intentions for justice and freedom irrevocably compromised and perverted. By crossing “a line beyond heroic exceptionality”,41 Batman blurs the line between good and evil.

“Why so serious?”42 While Burton and Nicholson contrive the Joker in Batman (1989)

as a postmodern homicidal artist celebrating insanity as freedom, Nolan retraces the archetype of the clown to his anarchistic roots. With twisted bodies, grotesque faces and nonsensical tirades, jesters in the Middle Ages offered criticism of the social status quo from the perspective of an outsider, inverting courtly and ecclesiastical norms with their devilish antics and exposing in their masquerades the duplicity of society. The jester was the ambassador of a netherworld from which humans could find their way back to the chaotic origins of life. Heath Ledger’s Joker joins this tradition. As an agent of chaos he creates disorder and rocks the “schemers” to demonstrate the fragility of ideologically shaped worldviews. He inverts everything there is into its opposite. In his last encounter with Batman, the Joker dangles upside down on the Dark Knight’s rope. While he explains his twisted worldview, the camera slowly rotates 180 degrees, until he is upright again and Gotham’s night sky upside down. The Joker is a master of deception – with or without make-up, as corpse or as nurse. the fact that he has no secret identity, that his entire appearance functions as a whole-body mask links him directly to medieval fools who, according to Mikhail Bakhtin, “were not actors playing parts on stage … but remained fools and clowns always and wherever they made their appearance”.43 With his disconcerting speech patterns, gestures and way of walking, the Joker does not seem to be of this world, but rather has stepped out of the liminal world of carnival. He repeatedly calls attention to his mouth, highlighting his scars with red lipstick, smacking his lips, grinning and holding it directly into the camera (see fig. 20). In the subversive theatricality of the carnival, the concept of the grotesque body concentrates in the gaping mouth, for Bakhtin the symbol of a “wide-open bodily abyss”.44 The Joker’s mouth gapes like a large wound in his face; by conjuring a smile onto his victim’s face with a knife, he lets that victim share his own limitless blackness.

The face is the leitmotif of the film. Recalling Béla Balázs’ early film theory of the visualization of man through his physiognomy on screen,45 the faces in The Dark Knight (2008) become an important carrier of meaning (see fig. 21). Looking into the painted visage of the Joker, one gets caught up in the maelstrom of his infinite malignity. In contrast, Batman’s masked face becomes a symbol of resistance and hope, an immortal ideal that inspires people to follow his lead in the fight against crime. Unfortunately, his freely interpretable face also allows people to misconceive his ideal, as militant copycats take up arms and act against his intentions. Finally, there is the face of district attorney Harvey Dent (Aaron Eckhart), whose all-American look becomes a surface for projected hopes and optimism: “Look at this face. This is the face of Gotham’s bright

future”, Bruce Wayne declares at his fundraising party.46 Dent is Gotham’s shining white knight, a hero with a face that eventually could suspend the need for a masked Dark Knight. Behind this façade, however, lies a second face – two-face. Dent’s flaw is his moral intransigency. In his monochrome worldview, good and evil are so widely separated that the self-righteous attorney cannot connect to his darker side, which erupts in occasional outbursts and acts of desperation. Dent’s case alludes to the Strange Case of Dr Jekyll and Mr Hyde (1886), Robert Louis Stevenson’s famous examination of human nature’s duality. Like Jekyll, Dent tries at all costs to hide his evil other, because he does not recognize it as part of his own self. Therefore, all it takes is a “little push” from the Joker and Harvey’s world is turned upside down. Deprived of the love of his life and left with serious physical and mental injuries, his moral bigotry is gruesomely written in his face in the figure of the Janus-like Two-Face. After his departure from good, the only consistent option left to him is to join with evil: “Either you die a hero or you live long enough to see yourself become the villain.”47 The motif of the face turns into the image of a coin where everything has a reverse side (see fig. 22–27). Two-Face lost his faith in the right decision and his decision-making ability. instead of being the master of his own destiny, he despairs of the cruel arbitrariness of human existence. This shift is symbolized by his lucky coin. At the beginning, the coin had two identical sides, thus negating the possibility of loss and highlighting his full control over life: “I make my own luck.”48 In the explosion that kills his fiancée, Rachel (Maggie Gyllenhaal), the coin, like he himself is burned on one side. incapable of accepting the tension of duality and of being at one with himself, he now leaves all life and death

decisions to chance, his new god of justice: “The only morality in a cruel world is chance. Unbiased. Unprejudiced. Fair.”49 Harvey’s lapse provides the backbone of the film’s narrative. Evil has won. The Joker brought down the best and turned him into an insane cop killer. But the good must not lose, heroic stories are supposed to have a happy ending. So the result is marked: Batman takes on responsibility for two-face’s crimes and is hunted by the police, while Harvey Dent died a hero’s death and becomes the legend that Batman always wanted to be. Gotham’s peace is restored, but on the basis of a lie: “Sometimes the truth is not good enough. Sometimes people deserve more.”50 This outcome is a clear reference to John Ford’s late Western The Man Who Shot Liberty Valance (US 1962), in which the forged legend of a town’s hero becomes a constitutive social truth. For Vincent M. Gaine, this compromise “problematizes the ‘natural, unquestionable justice’ favored by superhero narratives”.51 The ending of The Dark Knight (2008) evidently demonstrates that good and evil have no individual ontological status but are reciprocally constructed and conceptualized via storytelling. Thus Batman really is a floating signifier, for he can take on any role the city needs him to fulfill, enabled by the public: “Batman can convincingly play the dark knight only because his role was perceived as (potentially) evil from the outset – at least by a few. While Batman is the one who theatrically produces signs, those few represent the constitutive counterpart.”52

Shadows of the bat

The dual cosmology of Manichaeism, which underlines the superhero narrative of the hero’s fight against the villain, eventually serves as an explanation for the origin and essence of evil itself. Mani’s belief system is based on the fundamental question, “Why does evil exist?”53 In his view, evil does not exist as a lack of good, but as a real, powerful force that actively intervenes with the world. Evil opposes and negates everything that is good and pure; it seduces man to commit sin. Although corresponding with the notion of Satan in Christianity, Mani’s binary belief contradicts the Christian dictates of monotheism, as the existence of an equally powerful counterforce denies the omnipotence of God. Nevertheless, the ideas of Manichaeism have influenced Western thinking until today. The image of a metaphysical evil as the ultimate adversary, as the devil who has to be fought with all means, can be found, for example, in the rhetoric

of enemy stereotypes. Invoked bogeymen whose very existence threatens the Western value system, like the Germans during the World Wars, the Soviets in the Cold War or the Islamist terrorist of present day, carry a clear political function. Exploiting the fears, insecurities and prejudices of a community, enemy images help to simplify things in a complicated, globalized world by pinpointing a scapegoat. They strengthen a weakened group identity via exclusion and serve as a means of justification for a political agenda.54 The United States, in particular, has a long tradition of enemy images. In times of war and conflict, American politicians constantly evoke the Manichaean rhetoric of good versus evil, posing God’s chosen people against foreign enemies of freedom and democracy. Considering the terrorist attacks of 11 September 2001, George W. Bush declared that the United States were “at war” and famously labeled enemy states like North Korea, Iran and Iraq, which seek weapons of mass destruction and allegedly support terrorism, an “axis of evil”.55 Throughout his presidency, he constituted a bipolar world of “freedom” and “fear”, “us” and “them”.56

In their Batman movies, Tim Burton and Christopher Nolan visualize the dynamics of enemy images; they deconstruct the Manichaean worldview by illustrating its flipside and highlighting its fragility. In place of the dualistic belief system, their movies propose an alternative discourse about the nature and origin of evil. In the case of Batman Returns (1992), Burton tells a modern fairytale about good and evil from the perspective of the rejected other. He lets us partake in the “personal catharsis” he gains from identification with “characters who are both mentally and physically different”:57 He renders Batman, Penguin and Catwoman non-conformists who use their alleged otherness to express their independency and are therefore sanctioned by a hostile collective. For that, Burton utilizes the gothic imagery of horror movies he grew up with, but reverses it. Originally, the monster in classic U.S. horror films was depicted as an inhuman, external force of evil that invades the idyllic harmony of everyday American life. Thereby it has often functioned as a coded sign for contemporary images of the enemy58 and a social panic that the traditional order within the sexes, races and classes could collapse.59 In Batman Returns (1992), monstrosity is a sign not of evil, but of isolating individuality, while the so-called normalcy conceals true viciousness. Like the pitiable creature (Boris Karloff) in James Whale’s Frankenstein (US 1931), Burton’s monsters are inherently innocent; it is the confrontation with a xenophobic society that makes them evil.

In The Dark Knight (2008), Nolan demonstrates his deep passion for fictionality and storytelling as he exposes the duality of good and evil as a key rhetoric in the narrative of a society that uses these terms to justify its actions. On the surface, the Joker incarnates the enemy image of a terrorist, as he is represented as a resourceful force of destruction that cannot be negotiated with, a mad man determined to watch the world burn. His real intentions, however, are to face Gotham’s inhabitants with their own viciousness, which primarily resides in their utilitarian ethics of “scheming”. For him, cops and criminals behave the same, for they are enslaved to the selfish object of their plan. In his sadistic games of life and death, he confronts the people of Gotham with the “logic of their scheming taken to its end point”, but also “provides an opportunity for them to break out of calculation”.60 So the Joker’s evil is actually the basis for the hero’s ethics. Ultimately, The Dark Knight (2008) is not about the nature of evil, but about the way it is fought by the good. Does Batman make the right decision? Are his means just? Reflecting America’s ongoing War on Terror, the movie refuses to give an unequivocal answer. Instead, the movie implies a shifting, fluid moral universe where the characters embody contradictory, unstable positions.61 Because of this complexity, some interpreted the movie as praise for Bush’s conservative policies, where the boundaries of civil rights were pushed in order to “deal with an emergency”.62 Others, however, saw Batman’s use of torture and a problematic surveillance technology as critique of the Bush regime.63 from reactionary to subversive, the movie’s political message above all lies in “the blurring of boundaries” and “instability of oppositions”,64 favoring ambiguity over simplistic duality. Tim Burton and Christopher Nolan persuasively question the clear separation of good and evil as well as their ontological statuses. They unmask them as ideological attributions often misused for propaganda, as makeshift explanatory patterns for complex human behavior. Consequently, their Batman movies exhibit that the struggle between good and evil is fought not externally, but internally. Moving from the subject of morality to a broader scale, the dispute between contrary principles articulates the antagonistic tendencies in the individual, which are constantly fighting.65 There the fictional representations of good and evil function as interchangeable metaphors for the many dichotomies that define human nature, whether in the conflict

between individuality and conformity, inside and outside, normal and abnormal (Batman Returns, 1992) or the fight between order and chaos, justice and vengeance, rule and exception (The Dark Knight, 2008). What image could be more suitable, then, to illustrate these antagonisms than the shadowy figure of Batman, the very representation of duality itself? His whole nature as Batman, as semi-entity, symbolizes the permeability of boundaries as he unites hero and villain, light and darkness, man and beast, idea and matter (see fig. 28). Among his clownish foes and circus counterparts, Batman is the true embodiment of the trickster archetype. He shifts between worlds, defies clear categories and signifies ambivalence. His multiplicity attracts artists like Burton and Nolan, who can express their individual vision through the versatility of his image.

Bibliography

Bakhtin, Mikhail, 1984, Rabelais and His World, Bloomington: Indiana University Press. Balázs, Béla, 2011, Early Film Theory. Visible Man and the Spirit of Film, New York/Oxford: Berghahn Books.

Boichel, Bill, 1991, Batman. Commodity as Myth, in: Pearson, Roberta/Uricchio, William (eds.), The Many Lives of Batman. Critical Approaches to a Superhero and His Media, New York: Routledge, 4–17.

Brooker, Will, 2012, Hunting Down the Dark Knight. Twenty-First Century Batman, London: I.B. Tauris.

Bush, George W., 2002, The President’s State of the Union Address, The United states Capitol, Washington, D.C., 29 January 2002. https://georgewbush-whitehouse.archi…020129-11.html [accessed 26 September 2016].

Campbell, Joseph/Moyers, Bill, 1988, The Power of Myth, New york: Doubleday. Coogan, Peter, 2006, Superhero. the secret Origin of a Genre, Austin, TX: MonkeyBrain Books.

Coyle, Kevin J., 2009, Manichaeism and its Legacy, Leiden/Boston: Brill.

Danesi, Marcel, 2016, The “Dexter Syndrome”. The Serial Killer in Popular Fiction, New York: Peter Lang.

DiPaolo, Marc, 2011, War, Politics and Superheroes. Ethics and Propaganda in Comics and Film, Jefferson, NC: Mcfarland.

Doty, Alexandra/Ingham, Patricia Clare, 2004, The “Evil Medieval”. Gender, Sexuality, Miscegenation and Assimilation in Cat People, in: Pomerance, Murray (ed.), Bad. Infamy, Darkness, Evil, and Slime on Screen, Albany: State University of New York Press, 225–238.

fiebig-von hase, ragnhild (ed.), 1997, enemy images in American history, Providence, ri: Berghahn.

fischer-Lichte, erika, 1995, i – theatricality introduction. theatricality. A Key Concept in theatre and Culture studies, in: theatre research international, 20, 2, 85–89.

Gaine, Vincent M., 2011, Genre and super-heroism. Batman in the New Millennium, in: Gray, richard J., ii/Kaklamanidou, Betty (eds.), the 21st Century superhero. essays on Gender, Genre and Glo- balization in Film, Jefferson (NC): McFarland, 111–128.

Gray, richard J., ii/Kaklamanidou, Betty (eds.), 2011, the 21st Century superhero. essays on Gender, Genre and Globalization in Film, Jefferson, NC: McFarland.

hanke, Ken, 2007, tim Burton, in: Woods, Paul A. (ed.), tim Burton. A Child’s Garden of Nightmares, London: Plexus, 81–96.

Heger, Christian, 2010, Mondbeglänzte Zaubernächte. Das filmische Universum von Tim Burton, Marburg: schüren.

hickethier, Knut, 2008, Das narrative Böse – sinn und funktionen medialer Konstruktionen des Bös- en, in: faulstich, Werner (ed.), Das Böse heute. formen und funktionen, Paderborn: Wilhelm fink, 227–244.

Ip, John, 2011, the Dark Knight’s War on terrorism, Ohio state Journal of Criminal Law, september 2011, 209–229. Available at ssrN: http://ssrn.com/abstract=1574539 [accessed 26 september 2016].

Klavan, Andrew, 2008, What Bush and Batman have in Common, in: the Wall street Journal, updat- ed 25 July 2008. http://www.wsj.com/articles/SB121694247343482821 [accessed 26 september 2016].

Langley, travis, 2012, Batman and Psychology. A Dark and stormy Knight, hoboken: John Wiley & sons.

Levitz, Paul, 2015, Man, Myth and Cultural icon, in: Pearson, roberta/Uricchio, William/Brooker, Will (eds.), Many More Lives of the Batman, London: Palgrave, 13–20. Lyotard, Jean-françois, 1997, the Postmodern Condition. A report on Knowledge, Manchester: Manchester University Press.

McGowan, todd, 2012, the fictional Christopher Nolan, Austin, tX: University of texas Press.

Merschmann, helmut, 2000, tim Burton, Berlin: Bertz.

Moore, Alan, 2008, the Killing Joke. the Deluxe edition, New york: DC Comics.

Muller, Christine 2011, Power, Choice, and september 11 in the Dark Knight, in: Gray, richard J., ii/ Kaklamanidou, Betty (eds.), the 21st Century superhero. essays on Gender, Genre and Global- ization in Film, Jefferson, NC: McFarland, 46–60.

Mulvey, Laura, 1999, Visual Pleasure and Narrative Cinema, in: Braudy, Leo/Cohen, Marshall, film theory and Criticism. introductory readings, New york: Oxford University Press, 833–844.

Norden, Martin f., 2007, the “Uncanny” relationship of Disability and evil in film and television, in: Norden, Martin f. (ed.), the Changing face of evil in film and television, Amsterdam: rodopi, 125–144.

regalado, Aldo J., 2015, Bending steel. Modernity and the American superhero, Jackson: University Press of Mississippi.

Reinhart, Mark S., 2005, The Batman Filmography. Live-Action Feature, 1943–1997, Jefferson, NC: Mcfarland.

reynolds, David, 2011, superheroes. An Analysis of Popular Culture’s Modern Myths, Kindle edition.

reynolds, richard, 1992, super heroes. A Modern Mythology, Jackson: University Press of Mississippi.

salisbury, Mark (ed.), 2006, Burton on Burton, London: faber and faber.

schlegel, Johannes/habermann, frank, 2011, “you took My Advice about theatricality a Bit … Lit- erally”. theatricality and Cybernetics of Good and evil in Batman Begins, The Dark Knight, Spi- der-Man, and X-Men, in: Gray, richard J., ii/Kaklamanidou, Betty (eds.), the 21st Century super- hero. essays on Gender, Genre and Globalization in film, Jefferson, NC: McFarland, 29–45.

Seeßlen, Georg/Jung, Ferdinand, 2006, Horror. Geschichte und Mythologie des Horrorfilms, Marburg: schüren.

stoker, Bram/Auerbach, Nina/skal, David J. (eds.), 1997, Dracula, Norton Critical edition, New york: Norton.

Uricchio, William/Pearson, roberta, 1991, “i’m Not fooled by that Cheap Disguise”, in: Pearson, roberta/Uricchio, William (eds.), the Many Lives of Batman. Critical Approaches to a superhero and his Media, New york: routledge, 182–213.

Vogler, Christopher, 2007, the Writer’s Journey. Mythic structures for Writers, 3rd ed., studio City: Wiese.

Wagner, Carsten, 2009, sie kommen! Und ihr seid die Nächsten! Politische feindbilder in hollywoods horror- und science-fiction-filmen, Marburg: tectum-Verlag.

Worland, rick, 1997, OWi Meets the Monsters. hollywood horror films and War Propaganda, 1942 to 1945, Cinema Journal, 37, 1, 47–65.

Filmography

Batman (tim Burton, Us 1989). Batman (tV series, Us 1966–1968). Batman & Robin (Joel schumacher, Us 1997). Batman Begins (Christopher Nolan, Us 2005). Batman Forever (Joel schumacher, Us 1995). Batman Returns (tim Burton, Us 1992). Cat People (Jacques tourneur, Us 1942). Das Kabinet des Dr. Caligari (The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari, robert Wiene, De 1920).

Shadows of the Bat | 103 www.jrfm.eu 2017, 3/1, 75–104

Dracula (tod Browning, Us 1931). Frankenstein (James Whale, Us 1931). Hellboy (Guillermo del toro, Us 2004). Nosferatu, eine Symphonie des Grauens (Nosferatu – A Symphony of Horror, friedrich Wilhelm

Murnau, De 1922). The Bat Whispers (roland West, Us 1930). The Dark Knight (Christopher Nolan, Us 2008). The Dark Knight Rises (Christopher Nolan, Us 2012). The Man Who Laughs (Paul Leni, Us 1928). The Man Who Shot Liberty Valance (John ford, Us 1962). Unbreakable (M. Night shyamalan, Us 2000).

Notes

1 The Dark Knight (2008), 02:08:31–02:08:35.

2 Reynolds 2011.

3 DiPaolo 2011, 5.

4 Gray ii/Kaklamanidou 2011, 3.

5 Reynolds 1992, 51.

6 Lyotard 1997, xxiv–xxv.

7 Schlegel/Habermann 2011, 31.

8 Uricchio/Pearson 1991, 186.

9 Brooker 2012, 79–83.

10 Levitz 2015, 15.

11 Boichel 1991, 6.

12 Danesi 2016, 19.

13 see Vogler 2007, 23–80.

14 Campbell/Moyers 1988, 151.

15 Regalado 2015, 120.

16 Langley 2012, 170–171.

17 Regalado 2015, 122.

18 Langley 2012, 268.

19 Moore 2008, 42.

20 Batman (1989), 01:50:50–01:50:52.

21 The Dark Knight (2008), 01:24:32–01:24:34.

22 Brooker 2012, 138.

23 Coogan 2006, 105.

24 Batman Returns (1992), 00:42:13–00:42:17. The line is an obvious reference to Helen Reddy’s hymn of the women’s right movement from 1972: “I am woman. hear me roar!” See Heger 2010, 200.

25 See Dotyingham 2004.

26 See Mulvey 1999.

27 Heger 2010, 174.

28 Batman Returns (1992), 01:32:21–01:32:23.

29 Batman Returns (1992), 01:34:01–01:34:03.

30 Merschmann 2000, 64–65.

31 Reinhart 2005, 175–176.

32 Salisbury 2006, 103.

33 See Norden 2007.

34 Batman Begins (2005), 02:04:50–02:05:04.

35 McGowan 2012, 135.

36 Fischer-Lichte 1995, 88.

37 DiPaolo 2011, 59.

38 regalado 2015, 227.

39 Muller 2011, 58.

40 The Dark Knight (2008), 01:26:32–01:26:39.

41 McGowan 2012, 130.

42 The Dark Knight (2008), 00:29:27–00:29:30.

43 Bakhtin 1984, 8.

44 Bakhtin 1984, 317.

45 See Balázs 2011.

46 The Dark Knight (2008), 00:43:27–00:43:31.

47 The Dark Knight (2008), 00:20:01–00:20:05.

48 The Dark Knight (2008), 00:13:50–00:13:51.

49 The Dark Knight (2008), 02:12:30–02:12:40.

50 The Dark Knight (2008), 02:17:03–02:17:09.

51 Gaine 2011, 128.

52 Schlegel/Habermann 2011, 35.

53 See Coyle 2009, xiv.

54 See Fiebig-Von Hase 1997, 1–40.

55 Bush 2002.

56 See Wagner 2009, 31.

57 Hanke 2007, 95.

58 See Worland 1997.

59 Seeßlen/Jung 2006, 127.

60 McGowan 2012, 141.

61 Brooker 2012, 204–207.

62 Klavan 2008.

63 ip 2011, 229.

64 Brooker 2012, 207.

65 See Hickethier 2008, 238.

____________________

Simon Born studied Media Dramaturgy at the Johannes Gutenberg University of Mainz, Germany, and is currently working on his doctoral thesis at the University of Siegen. This essay was originally published in the Journal for Religion, Film and Media.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License