3.3 The Rhetorical Triangle

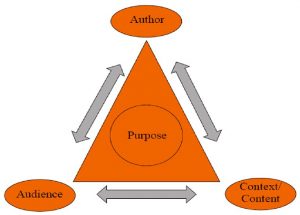

[1]As discussed throughout this chapter, any piece of writing is shaped by external and internal factors. These factors are referred to as the rhetorical situation, or rhetorical context, and are often presented in the form of a triangle.

The four key factors– author, audience, context, and content –all work together to influence the text’s purpose and how successful the author is in conveying that purpose to his or her audience. In order to successfully rhetorically analyze any medium, you have to understand each of these aspects and how they not only affect the other aspects but how they are affected by the other aspects as well.

Tip

These aspects also have to be understood, analyzed, and applied to your own writing in order to create highly successful papers, projects, speeches, etc.

Purpose

Any time you are preparing to write, you should first ask yourself, “Why am I writing?” All writing, no matter the type, has a purpose. The purpose will sometimes be given to you (by a teacher, for example), while other times, you will decide for yourself. As the author, it’s up to you to make sure that the purpose is clear not only for yourself but also for your audience. If your purpose is not clear, your audience is not likely to receive your intended message.

There are, of course, many different reasons to write (e.g., to inform, to entertain, to persuade, to ask questions), and you may find that some writing has more than one purpose. When this happens, be sure to consider any conflict between purposes, and remember that you will focus on one main purpose as the primary reason why you are engaging with that audience.

Bottom line: Thinking about your purpose before you begin to write can help you create a more effective piece of writing.

Why Purpose Matters

- If you’ve ever listened to a lecture or read an essay and wondered “so what” or “what is this person talking about,” then you know how frustrating it can be when an author’s purpose is not clear. By clearly defining your purpose before you begin writing, it’s less likely you’ll be that author who leaves the audience wondering.

- If readers can’t identify the purpose of a text, they usually quit reading. You can’t deliver a message to an audience who quits reading.

- If a teacher can’t identify the purpose in your text, they will likely assume you didn’t understand the assignment and, chances are, you won’t receive a good grade.

Useful Questions

Consider how the answers to the following questions may affect your writing:

- What is my primary purpose for writing? How do I want my audience to think, feel, or respond after they read my writing?

- Do my audience’s expectations affect my purpose? Should they?

- How can I best get my point across (e.g., tell a story, argue, cite other sources)?

- Do I have any secondary or tertiary purposes? Do any of these purposes conflict with one another or with my primary purpose?

Using Rhetorical Analysis outside of your own work

While this section was about how to think of purpose before begining your own work, the same ideas apply in reverse. If you are engaging with a medium that you did not write, the first step in determining if the author(s) was successful is to determine what the purpose of that medium was. If you are unable to locate or succinctly explain what the purpose of a piece was, it is likely that the author(s) was not successful in conveying his or her intended purpose to the audience or that you were not the intended audience and therefore are unable to find the purpsoe. The second of these comes into play if you are reading or engaging with a conversation that was written for an audience that are experts in the field.

Rhetorical Analysis Practice

Once you locate the purpose, the next step is to determine which other parts of the rhetorical situation affected that purpose. What decisions did the author have to make in order to ensure that they were able to successfully convey that purpose to their intendened audience?

Audience

In order for your writing to be maximally effective, you have to think about the audience you’re writing for and adapt your writing approach to their needs, expectations, backgrounds, and interests. Being aware of your audience helps you make better decisions about what to say and how to say it. For example, you have a better idea if you will need to define or explain any terms, and you can make a more conscious effort not to say or do anything that would offend your audience.

Sometimes you know who will read your writing – for example, if you are writing an email to your boss. Other times you will have to guess who is likely to read your writing – for example, if you are writing a newspaper editorial. You will often write with a primary audience in mind, but there may be secondary and tertiary audiences to consider as well.

What to Think About

When analyzing your audience, consider these points. Doing this should make it easier to create a profile of your audience, which can help guide your writing choices.

Background-knowledge or Experience — In general, you don’t want to merely repeat what your audience already knows about the topic you’re writing about; you want to build on it. On the other hand, you don’t want to talk over their heads. Anticipate their amount of previous knowledge or experience based on elements like their age, profession, or level of education.

Expectations and Interests — Your audience may expect to find specific points or writing approaches, especially if you are writing for a teacher or a boss. Consider not only what they do want to read about, but also what they do not want to read about.

Attitudes and Biases — Your audience may have predetermined feelings about you or your topic, which can affect how hard you have to work to win them over or appeal to them. The audience’s attitudes and biases also affect their expectations – for example, if they expect to disagree with you, they will likely look for evidence that you have considered their side as well as your own.

Demographics — Consider what else you know about your audience, such as their age, gender, ethnic and cultural backgrounds, political preferences, religious affiliations, job or professional background, and area of residence. Think about how these demographics may affect how much background your audience has about your topic, what types of expectations or interests they have, and what attitudes or biases they may have.

Using Rhetorical Analysis outside of your own work

While this section was about how to think of audience before begining your own work, the same ideas apply in reverse. If you are engaging with a medium that you did not write, the first step in determining if the author(s) was successful in conveying his or her purpose to the intended audience is to determine who that audience was/is. To do this, you have to understand context/content and who the author was/is (see sections below). Answering the questions that come from those aspects of the rhetorical situation will help you pin down a specific audience and, usually, secondary and tertiary audiences as well. Once you determine what audience your author was writing/speaking to, you can then look at which tools/appeals (see 3.2) he or she used and decide rather or not they used those tools effectively.

Rhetorical Analysis Practice

Once you determine the audience, the next step is to determine how the other parts of the rhetorical situation affected how the author conveyed his/her purpose to that audience. How did who the author was/is professionally and personally affect they way they conveyed the message? What time were they writing/speaking in? Was somthing happening that caused that message to be particulalry effective? What did they say? Which appeals did they use and why?

Answering questions like with each part of the rhetorcial situation will help you begin to form connections between each part and between the parts and the purpose.

Author

The next unique aspect of anything written down is who it is, exactly, that does the writing. In some sense when you write, this is the part you have the most control over. You can harness the aspects of yourself that will make the text most effective to its audience, for its purpose.

Analyzing yourself as an author allows you to make explicit why your audience should pay attention to what you have to say, and why they should listen to you on the particular subject at hand.

Questions for Consideration

- What personal motivations do you have for writing about this topic?

- What background knowledge do you have on this subject matter?

- What personal experiences directly relate to this subject? How do those personal experiences influence your perspectives on the issue?

- What formal training or professional experience do you have related to this subject?

- What skills do you have as a communicator? How can you harness those in this project?

- What should audience members know about you, in order to trust what you have to tell them? How will you convey that in your writing?

Using Rhetorical Analysis outside of your own work

While this section was about how to think of the author before begining your own work, the same ideas apply in reverse. If you are engaging with a medium that you did not write, you have to look at how who the author is/was affected what he or she was presenting. To do this, you oftentimes have to look at the context (see section below). Answering the questions that come from that aspect of the rhetorical situation as well as filling in what you know about the author professionally and personally will help you pin down how he or she effected the medium. Once you analyze who the author was/is, you can then look at how those aspecs affected the way he or she used the rhetorical appeals (see 3.2).

Context and Content

These words are easy for students to get confused as they are one letter away from being the same word; however, they could not be further from one another in meaning. Context refers to what is happening outside of the speech/article/medium that caused the need for the thing to exist or affected what was said/presented in the medium. For example, in Dr. Martin Luther King Jr.’s speech “I Have a Dream,” he spoke during what some consider to be the peak of the Civil Rights Movement. This context not only affected what he said in his speech but how effective the examples he used were and who his audience was when he gave the speech. On the other hand, Content is what is contained within the medium. Continuing to use “I Have a Dream” as an example, while the context was the Civil Right Movement, the content was the words that MLK Jr. spoke at the Lincoln Memorial in 1963. The content might feel simple and as though it doesn’t play that large of a role in the rhetorical situation as a whole because it feels automatic or obvious; however, as you analyze the other aspects of the rhetorical situation, you will find that each of the other aspects directly impacts what was said, how it was said, in what order, etc.

Exercise

One of the best tricks to figuring out how the author, audience, context, and purpose affect a medium is to pretend something else happened or someone else was involved. Using “I Have a Dream” as an example, answer the following questions and discuss if these things would have changed the successfulness of or what was said in the speech.

- What if the President of the United States, JFK, gave the speech instead?

- What if MLK Jr. gave the speech 15 years earlier?

- What if the Civil Right Movement had already ended when he gave his speech?

- What if MLK Jr. gave the speech at his church in Alabama instead of the Lincoln Memorial?

Answering questions like these will help you see how the aspects of the rhetorical situation can determine if something is successful or not.

Media Attributions

- The rhetorical triangle created by Brittany Seay

- 3.3 (except where otherwise noted) was borrowed with edits and several additions from Academic Writing I by Lumen Learning which is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License ↵