1.2 The Logic Behind Doing Research and Writing Research Projects

[1]Research always begins with the goal of answering a question. In your quest to answer basic research questions, you turn to a variety of different sources for evidence: reference resources, people, evaluative and opinionated articles, and other sources. All along the way, you continually evaluate and re-evaluate the credibility of your sources.

Applying Research Skills

How did you decide to come to Connors State College? That decision was probably based on research. For example, you might have started with an internet search of “colleges near me,” or maybe you reviewed your high school’s concurrent student program. You probably talked to people and read about other schools. You may have spoken to admissions counselors or representatives from various schools. Whose advice did you trust more? On the one hand, the admissions counselors and representatives from a school have a lot of expertise, but they might also have some bias. On the other hand, your friends and family may have their own set of biases (e.g., maybe they want you to stay close to home). You had to navigate all of these claims and positions in order to decide on CSC. You’ll do much the same thing as an academic researcher: you will gather sources, both primary and secondary; analyze and evaluate them in relation to each other; and determine how they contribute to your project.

The reasons academics and scholars conduct research are essentially the same as the reasons someone does research on which university or college to attend: to find information and answers to questions with a method that has a greater chance of being accurate than a guess or a “gut feeling.” College professors in a history department, physicians at a medical school, graduate students studying physics, college juniors in a literature class, students in an introductory research writing class—all of these people are members of the academic community, and they all use research to find answers to their questions that have a greater chance of being “right” than making guesses or betting on feelings.

Students in an introductory research writing course are “academics,” the same as college professors. You might not think of yourself as being a part of the same group as college professors or graduate students, but when you enter a college classroom, you are joining the academic community in the sense that you are expected to use your research to support your ideas and you are agreeing to the conventions of research within your discipline. Another way of looking at it: first-year college students and college professors more or less follow the same “rules” when it comes to making points supported by research and evidence.

[2]Why Write Research Projects?

A lot of times, instructors and students tend to separate “thinking,” “researching,” and “writing” into different categories that aren’t necessarily very well connected. First, you think, then you research, and then you write. The reality is though that the possibilities and process of research writing are more complicated and much richer than that. We think about what it is we want to research and write about, but at the same time, we learn what to think based on our research and our writing. The goal of this book is to guide you through this process of research writing by emphasizing a series of exercises that touch on different and related parts of the research process.

But before going any further, you need to be aware of two important points about this book:

- This book is an introduction to academic writing and research, and chances are you will keep learning about academic writing and research after this class is over. You may have to take other writing classes where you will learn different approaches to the writing process, perhaps one where you will learn more about research writing in your discipline. However, even if this is your one and only “writing class” in your college career, you will have to learn more about academic writing for every class and every new academic writing project. Learning how to write well is not something that ends when the class ends. Learning how to write is an ongoing, life-long process.

- Academic writing is not the only kind of writing worth learning about, and it is not the only potential use for this book or this class. The focus of this book is the important, common, and challenging sort of writing students in a variety of disciplines tend to do, projects that use research to inform an audience and make some sort of point; specifically, academic research writing projects. But clearly, this is not the only kind of writing writers do.

Sometimes, students think introductory college writing courses are merely an extension of the writing courses they took in high school, and while this is true for some, the sort of writing required in college is different from the sort of writing required in high school. College writing tends to be based more on research than high school writing. Further, college-level instructors generally expect a more sophisticated and thoughtful interpretation of research from student writers which you looked at and studied in Composition 1. However, it is not enough to merely use more research in your writing than you did in high school or Composition 1; you also have to be able to think and write about the research you’ve done and are going to do.

Besides helping you write different kinds of projects where you use research to support a point, the concepts about research you will learn from this course will help you become better consumers of information and research. And make no mistake about it: information that is (supposedly) backed up by research is everywhere in our day-to-day lives. News stories we see on television or read in magazines or newspapers are based on research. Legislators use research to argue for or against the passage of the laws that govern our society. Scientists use research to make progress in their work.

Even the most trivial information we all encounter is likely to be based on something that at least looks like research. Consider advertising: we are all familiar with “research-based” claims in advertising like “four out of five dentists agree” that a particular brand of toothpaste is the best, or that “studies show” that a specific type of deodorant keeps its wearers “fresh” longer. Advertisers use research like this in their advertisements for the same reason that scientists, news broadcasters, magazine writers, and just about anyone else trying to make a point use research: it’s persuasive and convinces consumers to buy a particular brand of toothpaste.

This is not to say that every time we buy toothpaste we carefully mull over the research we’ve heard mentioned in advertisements. However, using research to persuade an audience must work on some level because it is one of the most commonly employed devices in advertising.

One of the best ways to better understand how we are effected by the research we encounter in our lives is to learn more about the process of research by becoming better and more careful critical readers, writers, and researchers. Part of that process will include the research-based writing you do in this course. In other words, this book will be useful in helping you deal with the practical and immediate concern of how to write essays and other writing projects for college classes, particularly ones that use research to support a point. But perhaps more significantly, these same skills can help you write and read research-based texts well beyond college.

Writing That Isn’t “Research Writing”

Not all useful and valuable writing automatically involves research or can be called “academic research writing.”

- While poets, playwrights, and novelists frequently do research and base their writings on that research, what they produce doesn’t constitute academic research writing. The film Shakespeare in Love incorporated facts about Shakespeare’s life and work to tell a touching, entertaining, and interesting story, but it was nonetheless a work of fiction since the writers, director, and actors clearly took liberties with the facts in order to tell their story. If you were writing a research project for a literature class which focuses on Shakespeare, you would not want to use Shakespeare in Love as evidence about how Shakespeare wrote his plays.

- Essay exams are usually not a form of research writing. When an instructor gives an essay exam, she usually is asking students to write about what they learned from the class readings, discussions, and lecturers. While writing essay exams demand an understanding of the material, this isn’t research writing because instructors aren’t expecting students to do additional research on the topic.

- All sorts of other kinds of writing we read and write all the time—letters, emails, journal entries, instructions, etc.—are not research writing. Some writers include research in these and other forms of personal writing, and practicing some of these types of writing—particularly when you are trying to come up with an idea to write and research about in the first place—can be helpful in thinking through a research project. But when we set about to write a research project, most of us don’t have these sorts of personal writing genres in mind.

So, what is “research writing”?

Research writing is writing that uses evidence (from journals, books, magazines, the Internet, experts, etc.) to persuade or inform an audience about a particular point.

Research writing exists in a variety of different forms. For example, academics, journalists, or other researchers write articles for journals or magazines; academics, professional writers, and almost anyone create web pages that both use research to make some sort of point and that show readers how to find more research on a particular topic. All of these types of writing projects can be done by a single writer who seeks advice from others, or by a number of writers who collaborate on the project.

Academic research writing—the specific focus of this textbook and the sort of writing project you will need to write in this class—is a form of research writing. How is academic research writing different from other kinds of writing that involve research? The goal of this textbook is to answer that question, and while academic research projects come in a variety of shapes and forms, in brief, academic research writing projects are a bit different from other kinds of research writing projects in three significant ways:

- Thesis: Academic research projects are organized around a point or a “thesis” that members of the intended audience would not accept as “common sense.” What an audience accepts as “common sense” depends a great deal on the audience, which is one of the many reasons why what “counts” as academic research varies from field to field. But audiences want to learn something new either by being informed about something they knew nothing about before or by reading a unique interpretation on the issue or the evidence.

- Evidence: Academic research projects rely almost exclusively on evidence in order to support this point. Academic research writers use evidence in order to convince their audiences that the point they are making is right. Of course, all writing uses other means of persuasion—appeals to emotion, to logic, to the credibility of the author, and so forth. But the readers of academic research writing projects are likely to be more persuaded by sound, schoarly evidence than by anything else.

- “Evidence,” the information you use to support your point, includes readings you find in the library (journal and magazine articles, books, newspapers, and many other kinds of documents); materials from the Internet (web pages, information from databases, other Internet-based forums); and information you might be able to gather in other ways (interviews, field research, experiments, and so forth).

- Citation: Academic research projects use a detailed citation process in order to demonstrate to their readers where the evidence that supports the writer’s point came from. Unlike most types of “non-academic” research writing, academic research writers provide their readers with a great deal of detail about where they found the evidence they are using to support their point. This process is called citation, or “citing” of evidence. It can sometimes seem intimidating and confusing to writers new to the process of academic research writing, but it is really nothing more than explaining to your reader where your evidence came from.

Writing as a Process: A Brief Explanation and Map

No essay, story, or book (including this one) simply “appeared” one day from the writer’s brain; rather, all writings are made after the writer, with the help of others, works through the process of writing.

Generally speaking, the process of writing involves:

- Coming up with an idea (sometimes called brainstorming, invention or “pre-writing”);

- Writing a rough draft of that idea;

- Showing that rough draft to others to get feedback (peers, instructors, colleagues, etc.);

- Revising the draft (sometimes many times); and

- Proof-reading and editing to correct minor mistakes and errors.

An added component in the writing process of research projects is, obviously, research. Rarely does research begin before at least some initial writing (even if it is nothing more than brainstorming or pre-writing exercises), and research is usually not completed until after the entire writing project is completed. Rather, research comes in to play at all parts of the process and can have a dramatic effect on the other parts of the process. Chances are you will need to do at least some simple research to develop an idea to write about in the first place. You might do the bulk of your research as you write your rough draft, though you will almost certainly have to do more research based on the revisions that you decide to make to your project.

There are two other things to think about within this simplified version of the process of writing. First, the process of writing always takes place for some reason or purpose and within some context that potentially changes the way you do these steps. The process that you will go through in writing for this class will be different from the process you go through in responding to an essay question on a Sociology midterm or from sending an email to a friend. This is true in part because your purposes for writing these different kinds of texts are simply different.

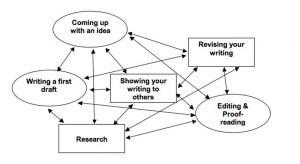

Second, the process of writing isn’t quite as linear and straight-forward as this list might suggest. Writers generally have to start by coming up with an idea, but writers often go back to their original idea and make changes to it after they write several drafts, do research, talk with others, and so on. The writing process might be more accurately represented like this:

Seem complicated? It is, or at least it can be.

So, instead of thinking of the writing process as an ordered list, you should think of it more as a “web” where different points can and do connect with each other in many different ways, and a process that changes according to the demands of each writing project. While you might write an essay where you follow the steps in the writing process in order (from coming up with an idea all the way to proofreading), writers also find themselves following the writing process out of order all the time. That’s okay. The key thing to remember about the writing process is that it is a process made up of many different steps, and writers are rarely successful if they “just write.”

But you should think of this textbook as being similar to a cookbook or an encyclopedia: you don’t have to read or use this book in this particular order, and you and your teacher don’t need to use all of this book in order to write successful research projects. On the other hand, like a cookbook or an encyclopedia, you should feel free to go back to passages you’ve read before. Remember: thinking through your research process should be systematic, but it isn’t necessarily a linear one.

Media Attributions

- Image by Steven D. Krause from The Process of Research Writing

- Borrowed with minor edits and additions from Research and Writing in the Disciplines with the 1CC LICENSED CONTENT of The Process of Research Writing by Steven D. Krause licensed under CC BY-NC-SA: Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike and Why do we research? by Andrew Davis which was provided by University of Mississippi and licensed under CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike ↵

- The rest of 1.2 (except where otherwise noted) was borrowed with minor edits and additions from The Process of Research Writing by Steven D. Krause licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-Share Alike 3.0 License ↵