2.5 Ethical Use and Citing Sources

[1]You likely know that research projects always need a reference or works cited page (also called a bibliography). But have you ever wondered why?

There are some “big picture” reasons that don’t often get articulated that might help you get better at meeting the citation needs of research projects. It’s helpful to understand both the theory behind citing, as well as the mechanics of it, to really become a pro.

In everyday life, we often have conversations where we share new insights with each other. Sometimes these are insights we’ve developed on our own through the course of our own everyday experiences, thinking, and reflection. Sometimes these insights come after talking to other people and learning from additional perspectives. When we relate the new things we have learned to our family, friends, or co-workers, we may or may not fill them in on how these thoughts came to us.

for arguments is often not provided. (Image source: XKDC)

Academic research leads us to the insight that comes from gaining perspectives and understandings from other people through what we read, watch, and hear. In academic work, we must tell our readers who and what led us to our conclusions. Documenting our research is important because people rely on academic research to be authoritative, so it is essential for academic conversations to be as clear as possible.

It is hard to talk about citation practices without considering some related concepts. Here are some definitions of those concepts that are often mentioned in assignments when citation is required.

What Is Academic Integrity?

The International Center for Academic Integrity defines academic integrity as a commitment, even in the face of adversity, to six fundamental values: honesty, trust, fairness, respect, responsibility, and courage. From these values flow principles of behavior that enable academic communities to translate ideals into action. The Fundamental Values of Academic Integrity describes these core values in detail and provides examples of how to put them into practice on campuses, in classrooms, and in daily life.[2]

In other words, you must take full responsibility for your work, acknowledge your own efforts, and acknowledge the contributions of others’ efforts. Working/Writing with integrity requires accurately representing what you contributed, as well as acknowledging how others have influenced your work. When you are a student, an accurate representation of your knowledge is important because it will allow both you and your professors to know the extent to which you have developed as a scholar. Part of that development is evidenced by how you apply the rules for acknowledging the work of others.

What Is Academic Misconduct?

As you might imagine, academic misconduct is when you do not use integrity in your academic work. Academic misconduct includes many different unacceptable behaviors, but the one most relevant to what we are discussing here are in bold below.

The absence of academic integrity is described as cheating, often defined as “the deceptions of others about one’s work.” Such acts may include but are not limited to the following list compiled by the Oklahoma State Regents for Higher Educations Advisory Council:

- Submitting another’s work as one’s own or allowing another to submit one’s work as though it were his or hers;

- Several people completing an assignment and turning in multiple copies all represented either implicitly or explicitly as individual work;

- Failing to contribute an equal share in group assignments or projects while claiming equal credit for the work;

- Using a textbook, notes, or technology tools during an examination without the permission of the instructor;

- Receiving or giving unauthorized help on assignment(s) or examinations(s);

- Stealing a problem solution or assessment answers from an instructor, a student, or other sources;

- Tampering with experimental data to obtain “desired” results, or creating results for experiments not done;

- Creating results for observations or interviews that were not done;

- Obtaining an unfair advantage by gaining or providing access to examination materials

- Tampering with or destroying the work of others;

- Submitting substantial portions of the same academic work for credit or honors more than once without permission of the present professor;

- Lying about these or other academic matters;

- Accessing computer systems or files without authorization;

- Plagiarizing (Plagiarism is generally defined as the use in one’s writing of specific words, phrases, and/or ideas of another without giving proper credit );

- Self-plagiarism is generally defined as a type of plagiarism in which the writer republished a work in its entirety or reuses portions of previously written text while authoring a new work;

- Falsifying college records, forms, or other documents.[3]

What Is Plagiarism?

As noted above, plagiarism can be intentional (knowingly using someone else’s work and presenting it as your own) or unintentional (inaccurately or inadequately citing ideas and words from a source). In either case, plagiarism puts both you and your professor in a compromising position.

While academic integrity calls for work resulting from your own effort, scholarship requires that you learn from others. So, in the world of academic scholarship, you are actually expected to learn new things from others AND come to new insights on your own. There is an implicit understanding that as a student you will be both using others’ knowledge as well as your own insights to create new scholarship. To do this in a way that meets academic integrity standards, you must acknowledge the part of your work that develops from others’ efforts. You do this by citing the work of others. You plagiarize when you fail to acknowledge the work of others and/or do not follow appropriate citation guidelines.

What Is Citing?

Citing, or citation, is a practice of documenting specific influences on your academic work.

In other words, you must cite all the sources you quote directly, paraphrase, or summarize as you:

- Answer your research question

- Convince your audience

- Describe the situation around your research question and why the question is important

- Report what others have said about your question

Why Cite Sources?

As a student, citing is important because it shows your reader (or professor) that you have invested time in learning what has already been learned and thought about the topic before offering your own perspective. It is the practice of giving credit to the sources that inform your work.

Our definitions of academic integrity, academic misconduct, and plagiarism give us important reasons for citing the sources we use to accomplish academic research. Here are several reasons for citing.

- To Avoid Plagiarism & Maintain Academic Integrity: Misrepresenting your academic achievements by not giving credit to others indicates a lack of academic integrity. This is not only looked down upon by the scholarly community, but it is also punished. When you are a student this could mean a failing grade on the assignment, a failing grade in that class for the semester, or even expulsion from the college.

- To Acknowledge the Work of Others: One major purpose of citations is to simply provide credit where it is due. When you provide accurate citations, you are acknowledging both the hard work that has gone into producing research and the person(s) who performed that research. Think about the effort you put into your work (whether essays, reports, or even non-academic jobs): if someone else took credit for your ideas or words, would that seem fair, or would you expect to have your efforts recognized?

- To Provide Credibility to Your Work & to Place Your Work in Context: Providing accurate citations puts your work and ideas into an academic context. They tell your reader that you’ve done your research and know what others have said about your topic. Not only do citations provide context for your work but they also lend credibility and authority to your claims.

Example

If you’re researching and writing about sustainability and construction, you should cite experts in sustainability, construction, and sustainable construction in order to demonstrate that you are well-versed in the most common ideas in the fields. Although you can make a claim about sustainable construction after doing research only in that particular field, your claim will carry more weight if you can demonstrate that your claim can be supported by the research of experts in closely related fields as well. Citing sources about sustainability and construction as well as sustainable construction demonstrates the diversity of views and approaches to the topic.

In addition, proper citation also demonstrates the ways in which research is social: no one researches in a vacuum—we all rely on the work of others to help us during the research process. - To Help Your Future Researching Self & Other Researchers Easily Locate Sources: Having accurate citations will help you as a researcher and writer keep track of the sources and information you find so that you can easily find the source again. Accurate citations may take some effort to produce, but they will save you time in the long run. So, think of proper citation as a gift to your future researching self!

Challenges in Citing Sources

Here are some challenges that might make knowing when and how to cite difficult for you. Our best advice for how to overcome these challenges is in the first item.

- Running Out of Time: When you are a student taking many classes simultaneously and facing many deadlines, it may be hard to devote the time needed to doing good scholarship and accurately representing the sources you have used. Research takes time. The sooner you can start and the more time you can devote to it, the better your work will be. From the beginning, be sure to include in your notes where you found the information you could quote, paraphrase, and summarize in your final product.

- Having to Use Different Styles: Different disciplines require that your citations be in different styles: which publication information is included and in what order. So your citations for different courses could look different, particularly for courses outside your major.

- Not Really Understanding the Material You’re Using: If you are working in a new field or subject area, you might have difficulty understanding the information from other scholars, thus making it difficult to know how to paraphrase or summarize that work properly.

- Shifting Cultural Expectations of Citation: Because of new technologies that make finding, using, and sharing information easier, many of our cultural expectations around how to do that are changing as well. For example, blog posts often “reference” other articles or works by simply linking to them. It makes it easy for the reader to see where the author’s ideas have come from and to view the source very quickly. But in these more informal writings, blog authors do not have a list of citations (bibliographic entries). The links do the work for them. This is a great strategy for online digital mediums, but this method fails over time when links break and there are no hints (like an author, title, and date) to know how else to find the reference, which might have moved. This example of a cultural change of expectations in the non-academic world might make it seem that there has been a change in academic scholarship as well, or might make people new to academic scholarship even less familiar with citation. But in fact, the expectations around citing sources in academic research remain formal.

Citation and Citation Styles

Citing sources is an academic convention for keeping track of which sources influenced your own thinking and research.

Most citations require two parts:

- The full bibliographic citation on the Bibliography page, References page, or Works Cited page of your final product.

- An indication within your text (usually author and publication date and maybe the page number[4] from which you are quoting) that tells your reader where you have used something that needs a citation.

With your in-text citation, your reader will be able to tell which full bibliographic citation you are referring to by paying attention to the author’s name and publication date.

Example: Citations in Academic Writing

Here’s a citation in the text of an academic paper:

Studies have shown that compared to passive learning, which occurs when students observe a lecture, students will learn more and will retain that learning longer if more active methods of teaching and learning are used (Bonwell &Eison, 1991; Fink, 2003).

The information in parentheses coordinates with a list of full citations at the end of the paper.

At the end of the paper, these bibliographic entries appear in a reference list[5]

Bonwell, C. C., & Eison, J. A. (1991). Active learning: Creating excitement in the classroom. 1991 ASHE-ERIC Higher Education Reports. ERIC Clearinghouse on Higher Education. https://eric.ed.gov/?id=ED336049

Fink, L. D. (2003). Creating significant learning experiences. Wiley.

Citation Styles

Style guides set the specific rules for how to create both in-text citations and their full bibliographic citations.

There are over a dozen kinds of citation styles. While each style requires much of the same publication information to be included in a citation, the styles differ from each other in formatting details such as capitalization, punctuation, order of publication information, and whether the author’s name is given in full or abbreviated.

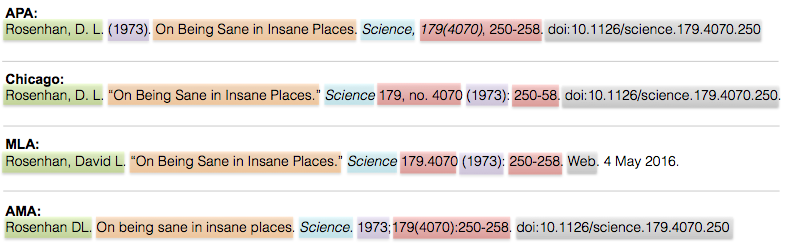

Example: Differences in Citation Styles

The image below shows bibliographic citations in four common styles. Notice that they contain information about who the author is, article title, journal title, publication year, and information about volume, issue, and pages. Notice also the small differences in punctuation, order of the elements, and formatting that do make a difference.

Compare citation elements (including the punctuation and spacing) in the same color to see how each style handles their information.

Steps for Citing

To write a proper citation we recommend following these steps, which will help you maintain accuracy and clarity in acknowledging sources.

Step 1: Choose Your Citation Style

Find out the name of the citation style you must use from your instructor, the directions for an assignment, or what you know your audience or publisher expects. Then search for your style at the Purdue Online Writing Lab (OWL) or use Google or Bing to find your style’s stylebook/handbook and then purchase it or ask for it at a library. You also have access to an OER APA Citation Manual

Step 2: Create In-Text Citations

Find and read your style’s rules about in-text citations, which are usually very thorough. Luckily, there are usually examples provided that make it a lot easier to learn the rules.

EXAMPLE: Style Guides Are Usually Very Thorough

For instance, your style guide may have different rules for when you are citing:

- Quotations rather than summaries rather than paraphrases

- Long, as opposed to short, quotations.

- Sources with one or multiple authors.

- Books, journal articles, interviews and email, or electronic sources.

Step 3: Determine the Kind of Source

After creating your in-text citation, now begin creating the full bibliographic citation that will appear on the References or Bibliography page by deciding what kind of source you have to cite (book, film, journal article, webpage, etc.).

Imagine that you’re using APA style and have your OER Handbook as a guide. In your psychogeography paper, you want to quote the authors of the book The Experience of Nature, Rachel Kaplan and Stephen Kaplan, which was published in 1989. What you want to quote is from page 38 of the book.

Here’s what you want to quote:

“The way space is organized provides information about what one might want to do in that space. A relatively brief glance at a scene communicates whether there is room to roam, whether one’s path is clear or blocked.”

- Skim the headings in the style guide to remind yourself of what its rules concern.

Since it has rules about the length of quotations, you count the number of words in what you want to quote and find that your quote has 38, which is within the range for short quotations (less than 40), according to the APA style guide. According to the rule for short quotations, you see that you’re supposed to introduce the quote by attributing the quote to the author (last name only) and adding the publication date in parentheses. You write:According to the Kaplans (1989), “The way space is organized provides information about what one might want to do in that space. A relatively brief glance at a scene communicates whether there is room to roam, whether one’s path is clear or blocked.”

- Then you notice that the example in the style guide includes the page number on which you found the quotation. It appears at the end of the quote (in parentheses and outside the quote marks but before the period ending the quotation). So you add that:

According to the Kaplans (1989), “The way space is organized provides information about what one might want to do in that space. A relatively brief glance at a scene communicates whether there is room to roam, whether one’s path is clear or blocked” (p. 38).

- You’re feeling pretty good, but then you realize that you have overlooked the rule about having multiple authors. You have two and their last names are both Kaplan. So you change your sentence to:

According to Kaplan and Kaplan (1989), “The way space is organized provides information about what one might want to do in that space. A relatively brief glance at a scene communicates whether there is room to roam, whether one’s path is clear or blocked” (p. 38).

So you have your first in-text citation for your final product:

According to Kaplan and Kaplan (1989), “The way space is organized provides information about what one might want to do in that space. A relatively brief glance at a scene communicates whether there is room to roam, whether one’s path is clear or blocked” (p. 38).

Step 4: Study Your Style’s Rules for Bibliographic Citations

Next, you’ll need a full bibliographic citation for the same source. This citation will appear on the References page. Bibliographic citations usually contain more publication facts than you used for your in-text citation, and the formatting for all of them is very specific.

EXAMPLE: Bibliographic Citation Rules Are Very Specific

- Rules vary for sources, depending, for instance, on whether they are books, journal articles, or online sources.

- Sometimes lines of the citation must be indented.

- Authors’ names usually appear last name first.

- Authors’ first names may be initials instead.

- Names of sources may or may not have to be in full.

- Names of some kinds of sources may have to be italicized.

- Names of some sources may have to be in quotes.

- Dates of publication appear in different places, depending on the style.

- Some styles require Digital Object Identifiers (DOIs ) in the citations for online sources.

Step 5: Identify Citation Elements

Figure out which bibliographic citation rules apply to the source you’ve just created an in-text citation for. Then apply them to create your first bibliographic citation.

Imagine that you’re using APA style and have your OER Handbook as a guide. Your citation will be for the book called The Experience of Nature, written by Rachel Kaplan and Stephen Kaplan and published in 1989.

- You start by trying to apply the basic rules of APA style, which tell you your citation will start with the last name of your author followed by his or her first initial, and that the second line of the citation will be indented. So you write: Kaplan, R. and Kaplan, S. and remind yourself to indent the second line when you get there.

- Since you have two authors, you look for a rule regarding that situation, which requires a comma between the authors and an ampersand between the names. So you write: Kaplan, R., & Kaplan, S.

- Because you know your source is a book, you look for style guide rules and examples about books. For instance, the rules for APA style say that the publication date goes in parentheses, followed by a period after the last author’s name. And that the title of the book is italicized. You apply the rules and examples and write the publication information you know about your source: Kaplan, R., & Kaplan, S. (1989). The Experience of Nature.

- You notice while following the format for the title of the book that the title of the book is in italics BUT every word is not capitalized and it doesn’t follow title case; it follows sentence case rules. So, you change your title to look like: Kaplan, R., & Kaplan, S. (1989). The experience of nature.[6]

- Next, you look at the rules and examples of book citations and notice that they show the publisher. So you find that information about your source (in a book, usually on the title page or its back) and write: Kaplan, R., & Kaplan, S. (1989). The experience of nature.

Cambridge University Press. - Congratulations, especially about remembering to add the hanging indent to that line! You have created the first bibliographic citation for your final product.

Step 6: Repeat the steps for creating an in-text citation and a bibliographic citation for each of your sources.

Create your bibliographic citation by arranging publication information to match the example you chose in Step 4. Pay particular attention to what is and is not capitalized and to what punctuation and spaces separate each part that the example illustrates.

Tip: Citation Software

It may seem like a great idea to quickly copy and paste the citation information that is generated for you using online citation software (like Citation Machine or Easy Bib) because you may be thinking “what is a few points lost after all”. However, it will actually cost you more and cause use you more issues in the long run. All online citation generators create incorrect reference entries[7] (some are worse than others). While the sheer volume of errors are the main issue with this plan, you are also limiting your ability to develop the skill needed to cite sources correctly and quickly.

We get it; citations are hard and the rules are overwhelming and seemingly pointless, but the more practice you put into this skill the larger the reward is. Grant your professors a little bit of trust and give citing a solid effort; it gets easier, and, sooner than you think possible, creating your own will be a thousand times easier than “losing points” or spending time editing the generated citations.[8]

When to Cite

Citing sources is often described as a straightforward, rule-based practice. But in fact, there are many gray areas around citation[9], and learning how to apply citation guidelines takes practice and education. If you are confused by it, you are not alone – in fact, you might be doing some good thinking.

Here are some guidelines to help you navigate citation practices.

Cite when you are directly quoting. This is the easiest rule to understand. If you are stating word-for-word what someone else has already written, you must put quotes around those words and you must give credit to the original author. Not doing so would mean that you are letting your reader believe these words are your own and represent your own effort.

Cite when you are summarizing and paraphrasing. This is a trickier area to understand. First of all, summarizing and paraphrasing are two related practices but they are not the same. Summarizing is when you read a text, consider the main points, and provide a shorter version of what you learned. Paraphrasing is when you restate what the original author said in a specific passage or phrase in your own words and in your own tone[10]. Both summarizing and paraphrasing require good writing skills and an accurate understanding of the material you are trying to convey. Summarizing and paraphrasing are difficult to do when you are a beginning academic researcher, but these skills become easier to perform over time with practice.

Cite when you are citing something that is highly debatable. For example, if you want to claim that the Patriot Act has been an important tool for national security, you should be prepared to give examples of how it has helped and how experts have claimed that it has helped. Many U.S. citizens concerned that it violates privacy rights won’t agree with you, and they will be able to find commentary that the Patriot Act has been more harmful to the nation than helpful. You need to be prepared to show such skeptics that you have experts on your side, too.

When Don’t You Cite?

Don’t cite when what you are saying is your own insight. As you learned, research involves forming opinions and insights around what you learn. You may be citing several sources that have helped you learn, but at some point, you must integrate your own opinion, conclusion, or insight into the work. The fact that you are not citing it helps the reader understand that this portion of the work is your unique contribution developed through your own research efforts.

Don’t cite when you are stating common knowledge. What is common knowledge is sometimes difficult to discern. In general, quick facts like historical dates or events are not cited because they are common knowledge.

Examples

- The Declaration of Independence was signed in 1776.

- Barack Obama became the 44th president of the United States in January, 2009.

Some quick facts, such as statistics, are trickier. For example, the number of gun-related deaths per year probably should be cited, because there are a lot of ways this number could be determined (does the number include murder only, or suicides and accidents, as well?) and there might be different numbers provided by different organizations, each with an agenda about gun laws.

A guideline that can help with deciding whether or not to cite facts is to determine whether the same data is repeated in multiple sources. If it is not, it is best to cite.

The other thing that makes this determination difficult might be that what seems new and insightful to you might be common knowledge to an expert in the field. You have to use your best judgment, and probably err on the side of over-citing, as you are learning to do academic research. You can also seek the advice of your instructor, a writing tutor, or a librarian. Knowing what is and is not common knowledge is a practiced skill that gets easier with time and with your own increased knowledge.

The answer to the ever-present question: Why Can’t I Cite Wikipedia?

You’ve likely been told at some point that you can’t cite Wikipedia, or any encyclopedia for that matter when you are creating an academic argument, in your scholarly work.

The reason is that such entries are meant to prepare you to do research, not be evidence of your having done it. Wikipedia entries, which are tertiary sources, are already a summary of what is known about the topic. Someone else has already done the labor of synthesizing lots of information into a concise and quick way of learning about the topic.

So, while Wikipedia is a great shortcut for getting context, background, and a quick lesson on topics that might not be familiar to you, don’t quote, paraphrase, or summarize from it. Just use it to educate yourself.

Activity: To Cite or Not to Cite?[11]

-

The fact that drunk driving is a major cause of auto fatalities.

-

a. To Cite

- b. Not to Site

-

-

The exact number of people who died in drunk-driving accidents between 2006 and 2008.

-

a. To Cite

-

b. Not to Cite

-

-

The idea that President Obama was a community organizer before he became a senator

-

a. To Cite

-

b. Not to Cite

-

-

A dollar amount representing President Obama’s financial imapct on Chicago’s south side.

-

a. To Cite.

-

b. Not to Cite.

-

-

The idea that the 21st century in the United States began with the 43rd president, George W. Bush.

-

a. To Cite

-

b. Not to Cite

-

-

The idea that human evolution is about the emergence of modern humans (homo sapiens) as a distinct species of hominids.

-

a. To Cite

-

b. Not to Cite

-

See footnotes for answers

In the next section, we are going to look at moving from research to categorizing and synthesizing the information you discover in your sources as you prepare to make your argument. There are varying ways that this is done and presented; however, for the sake of this book and time, we are only going to look at Annotated Bibliographies and Literature Reviews.

Media Attributions

- Lindsey MacCallum and Teaching & Learning Ohio State University Libraries

- “Wikipedian Protester” This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 2.5 License.

- Lindsey MacCallum and Teaching & Learning Ohio State University Libraries

- Ibid.

- Ibid.

- 2.5 (except where otherwise noted) was borrowed with minor edits and additions from Choosing & Using Sources: A Guide to Academic Research, 1st Canadian Edition by Lindsey MacCallum and Teaching & Learning Ohio State University Libraries which is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License ↵

- International Center for Academic Integrity [ICAI]. (2021). The Fundamental Values of Academic Integrity. (3rd ed.). www.academicintegrity.org/the-fundamental-values- of-academic-integrity. The Fundamental Values of Academic Integrity, Third Edition, from the International Center for Academic Integrity is available under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercialShareAlike 4.0 International license. ↵

- Make sure to check in your syllabus for the full CSC Academic Integrity policy. ↵

- Somtimes, you will even use a paragraph number if your source is completely online and does not use pagination. ↵

- The following entries are in APA style. ↵

- OER APA Handbook Rule ↵

- After all, it is a computer doing it based off of exactly what you type in and how you type it in. ↵

- "Tip: Citation Software" was written by Brittany Seay ↵

- While citation and the formatting rules are the most 'math-like' thing about writing, it still has some gray areas. For example, you are sure to encounter this firsthand when you watch your professor dig through a Citation Handbook trying to decide which source category your source is closest to. ↵

- Because paraphrasing is pulled from a specific section, the in-text citations typically include page numbers; however, summaries do not because you are referring to an entire work, not a single section. ↵

- 1. a; 2. a.; 3. b; 4. a; 5. b; 6. b ↵