2.2 Categorizing Sources

[1]Once you have your research question, you’ll need information sources to answer it and meet the other information needs of your research project.

This section about categorizing sources will increase your sophistication about them and save you time in the long run because you’ll understand the “big picture.” That big picture will be useful as you plan your own sources for a specific research project.

Typically, you will have many sources[2] available to meet the information needs of your projects. In today’s complex information landscape, just about anything that contains information can be considered a potential source.

Here is a more detailed list of potential source types

- Books and encyclopedias

- Websites, web pages, and blogs

- Magazine, journal, and newspaper articles

- Research reports and conference papers

- Field notes and diaries

- Photographs, paintings, cartoons, and other art works

- TV and radio programs, podcasts, movies, and videos

- Illuminated manuscripts and artifacts

- Bones, minerals, and fossils

- Preserved tissues and organs

- Architectural plans and maps

- Pamphlets and government documents

- Music scores and recorded performances

- Dance notation and theater set models

With so many sources available, the question usually is not whether sources exist for your project, but rather which ones will best meet your information needs.

Being able to categorize a source helps you understand the kind of information it contains, which is a big clue to (1) whether it might meet one or more of your information needs and (2) where to look for it and similar sources.

A source can be categorized by:

- Whether it contains quantitative or qualitative information or both

- Whether the source is objective (factual) or persuasive (opinion) and may be biased

- Whether the source is a scholarly, professional, or popular publication

- Whether the material is a primary, secondary, or tertiary source

- What format the source is in

As you may already be able to tell, sources can be in more than one category at the same time because the categories are not mutually exclusive.

Quantitative or Qualitative

One of the most obvious ways to categorize information is by whether it is quantitative or qualitative. Some sources contain either quantitative information or qualitative information, but sources often contain both.

Many people first think of information as something like what’s in a table or spreadsheet of numbers and words. But information can be conveyed in more ways than just textually or numerically.

Quantitative Information – Involves a measurable quantity—numbers are used. Some examples are length, mass, temperature, and time. Quantitative information is often called data, but can also be things other than numbers.

Qualitative Information – Involves a descriptive judgment using concept words instead of numbers. Gender, country name, animal species, and emotional state are examples of qualitative information.

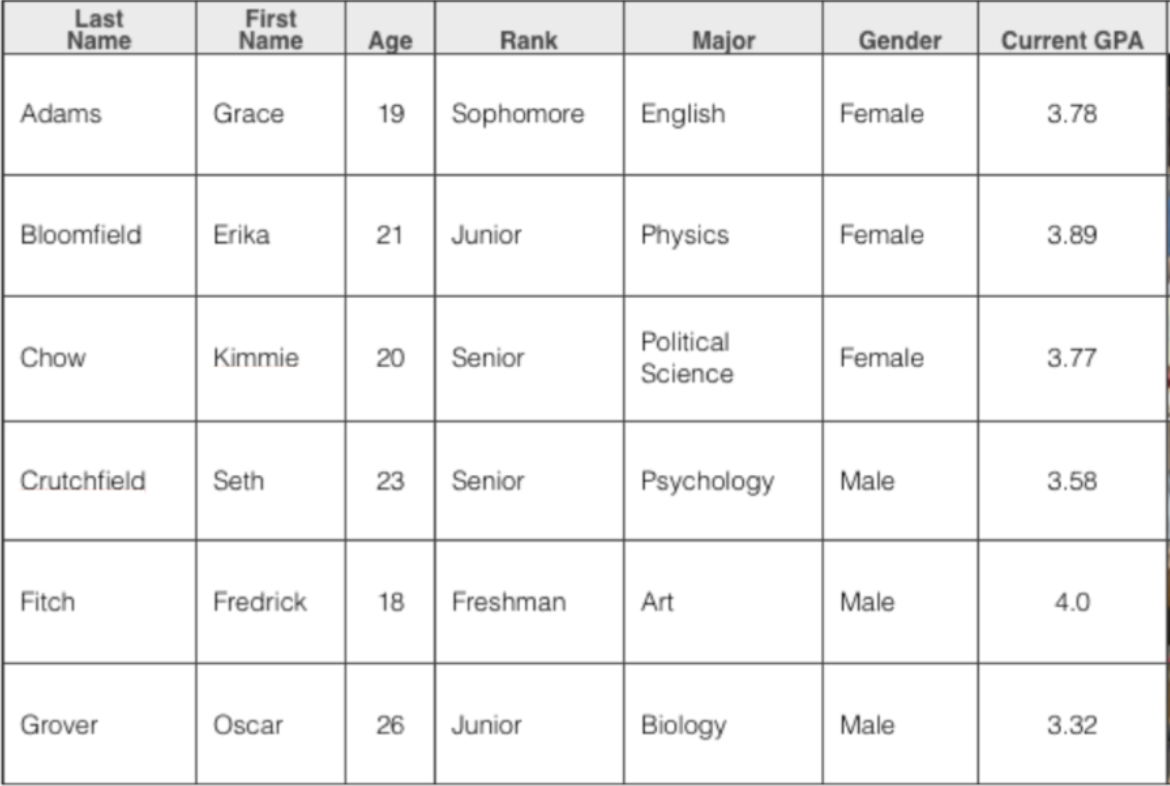

Take a quick look at the example table below. Another way we could display the table’s numerical information is in a graphic format —listing the students’ ages or GPAs on a bar chart, for example, rather than in a list of numbers. Or, all the information in the table could be displayed instead as a video of each student giving those details about themselves.

Example: Data Table with Quantitative and Qualitative Data

Increasingly, other formats (such as images, sound, and video) may be used as information or used to convey information.

Examples

- A video of someone watching scenes from horror movies, with information about their heart rate and blood pressure embedded in the video. Instead of getting a description of the person’s reactions to the scenes, you can see their reactions.

- A database of information about birds, which includes a sound file for each bird singing. Would you prefer a verbal description of a bird’s song or an audio clip?

- A list of colours, which include an image of the actual colour. Such a list is extremely helpful, especially when there are A LOT of colour names.

- A friend orally tells you that a new pizza place is 3 blocks away, charges $2 a slice, and that the pizza is delicious. This may never be recorded, but it may be very valuable information if you’re hungry!

- A map of Canada with provinces shaded different intensities of red according to the median household income of inhabitants.

Activities: Quantitative, Qualitative, and Data

- Activity: Quantitative vs. Qualitative[3]

- What quantitative and qualitative data components might you use to describe yourself?

- Activity: Multiple Data Displays[4]

- Take a look at the Wikipedia article about UN Secretaries-General. Scroll down and view the table of people who served as Secretary-General. In what ways is information conveyed in ways other than text or numbers?

See footnotes for possible answers

Fact or Opinion

Thinking about the reason an author produced a source can be helpful to you because that reason was what dictated the kind of information they chose to include. Depending on that purpose, the author may have chosen to include factual, analytical, and objective information. Or, instead, it may have suited their purpose to include information that was subjective and, therefore, less factual and analytical. The author’s reason for producing the source also determined whether they included more than one perspective or just their own.

Authors typically want to do at least one of the following:

- Inform and educate;

- Persuade;

- Sell services or products or;

- Entertain.

Combined Purposes

Sometimes authors have a combination of purposes, as when a marketer decides she can sell more smartphones with an informative sales video that also entertains us. The same is true when a singer writes and performs a song that entertains us but that she intends to make available for sale. Academic authors also produce work with multiple purposes.

In those cases, authors certainly want to inform and educate their audiences. But they also want to persuade their audiences that what they are reporting and/or postulating is a true description of a situation, event, or phenomenon, or a valid argument. In this blend of scholarly authors’ purposes, the intent to educate and inform is considered to trump the intent to persuade.

Why Intent Matters

Authors’ intent usually matters in how useful their information can be to your research project, depending on which information need you are trying to meet. For instance, when you’re looking for sources that will help you actually decide your answer to your research question or evidence for your answer that you will share with your audience, you will want the author’s main purpose to have been to inform or educate his/her audience. That’s because, with that intent, they are likely to have used:

- Facts where possible.

- Multiple perspectives instead of just their own.

- Little subjective information.

- Seemingly unbiased, objective language that cites where they got the information.

The reason you want that kind of resource when trying to answer your research question or explaining that answer is because all of those characteristics will lend credibility to the argument you are making with your project. Both you and your audience will simply find it easier to believe—will have more confidence in the argument being made—when you include those types of sources.

Sources whose authors intend only to persuade others won’t meet your information need for an answer to your research question or evidence with which to convince your audience. That’s because they don’t always confine themselves to facts. Instead, they tell us their opinions without backing them up with evidence. If you used those sources, your readers will notice and not believe your argument.[5]

Difference Between Fact, Opinion, Objective, and Subjective Information

Fact – Facts are useful to inform or make an argument.

Examples:

- The country of Canada was established in 1867.

- The pH levels in acids are lower than pH levels in alkalines.

- Beethoven was a composer and pianist.

Opinion – Opinions are useful to persuade, but careful readers and listeners will notice and demand evidence to back them up.

Examples:

- That was a good movie.

- Strawberries taste better blueberries.

- Beethoven’s reputation as a virtuoso pianist is overrated.

Objective – Objective information reflects a research finding or multiple perspectives that are not biased.

Examples:

- “Several studies show that an active lifestyle reduces the risk of heart disease and diabetes.”

- “Studies from the Brown University Medical School show that twenty-somethings eat 25 percent more fast-food meals at this age than they did as teenagers.”

Subjective – Subjective information presents one person or organization’s perspective or interpretation. Subjective information can be meant to distort, or it can reflect educated and informed thinking. All opinions are subjective, but some are backed up with facts more than others.

Examples:

- “The simple truth is this: as human beings, we were meant to move.”

- “In their thirties, women should stock up on calcium to ensure strong, dense bones and to ward off osteoporosis later in life.”*

*In this quote, it’s mostly the “should” that makes it subjective. The objective version of the last quote would read: “Studies have shown that women who begin taking calcium in their 30s show stronger bone density and fewer repercussions of osteoporosis than women who did not take calcium at all.” But perhaps there are other data showing complications from taking calcium. That’s why drawing the conclusion that requires a “should” makes the statement subjective.

Primary, Secondary, and Tertiary Sources

Another information category is called publication mode and has to do with whether the information is:

- Firsthand information: information in its original form, not translated or published in another form.

- Secondhand information: a restatement, analysis, or interpretation of original information.

- Third-hand information: a summary or repackaging of original information, often based on secondary information that has been published.

The three labels for information sources in this category are, respectively, primary sources, secondary sources, and tertiary sources. Here are examples to illustrate the first- handedness, second-handedness, and third-handedness of information:

| Primary Source

(Original, Firsthand Information) |

J.D. Salinger’s novel Catcher in the Rye. |

| Secondary Source

(Secondhand Information) |

A book review of Catcher in the Rye. Even if the reviewer has a different opinion than anyone else has ever published about the book, he or she is still just reviewing the original work and all the information about the book here is secondary. |

| Tertiary Source

(Third-hand Information) |

Wikipedia page about J.D. Salinger. |

When you make distinctions between primary, secondary, and tertiary sources, you are relating the information itself to the context in which it was created. Understanding that relationship is an important skill that you’ll need in college, as well as in the workplace. Noting the relationship between creation and context helps us understand the “big picture” in which information operates and helps us figure out which information we can depend on. That’s a big part of thinking critically.

Primary Sources – Because it is in its original form, the information in primary sources has reached us from its creators without going through any filter. We get it firsthand.

Examples

- Any literary work, including novels, plays, and poems.

- Breaking news.

- Diaries.

- Advertisements.

- Music and dance performances.

- Eyewitness accounts, including photographs and recorded interviews.

- Artworks.

- Data.

- Blog entries that are autobiographical.

- Scholarly blogs that provide data or are highly theoretical, even though they contain no autobiography.

- Artifacts such as tools, clothing, or other objects.

- Original documents such as tax returns, marriage licenses, and transcripts of trials.

- Websites, although many are secondary.

- Buildings.

- Correspondence, including email.

- Records of organizations and government agencies.

- Journal articles that report research for the first time (at least the sections of articles about the new research, plus their data).

Secondary Source – These sources are translated, repackaged, restated, analyzed, or interpreted original information that is a primary source. Thus, the information comes to us secondhand, or through at least one filter.

Examples

- All nonfiction books and magazine articles except autobiography.

- An article or website that critiques a novel, play, painting, or piece of music.

- An article or web site that synthesizes expert opinion and several eyewitness accounts for a new understanding of an event.

- The literature review portion of a journal article.

Tertiary Source – These sources further repackage the original information because they index, condense, or summarize the original.

Typically by the time tertiary sources are developed, there have been many secondary sources prepared on their subjects, and you can think of tertiary sources as information that comes to us “third-hand.” Tertiary sources are usually publications that you are not intended to read from cover to cover but to dip in and out of for the information you need. You can think of them as a good place for background information to start your research but a bad place to end up.

Examples

- Almanacs.

- Dictionaries.

- Guide books.

- Survey articles.

- Timelines.

- Bibliographies.

- Encyclopedias, including Wikipedia.

- Most textbooks.

Tertiary sources are usually not acceptable as cited sources in college research projects, as highlighted in 2.1, because they are so far from firsthand information. That’s why most professors don’t want you to use Wikipedia as a citable source: the information in Wikipedia is far from original information. Other people have considered it, decided what they think about it, rearranged it, and summarized it–all of which is actually what your professors want you, not another author, to do with information in your research projects.

Activity: Which Kind of Source?

Instructions: Assume that each of the sources below is relevant to research being done by a university student. Examine their titles and other information carefully to judge whether each is a primary, secondary, or tertiary source.[6]

- A field guide to snowy owls

- 29/2/2016 New York Times article headline “Otto Warmbier, Detained U.S. Student, Apologizes in North Korea”

- Stern’s Introductory Plant Biology (a textbook)

- Oxford Dictionary of Engineering

- “Health Functionality of Organo-sulfides: A Review” (a journal article)

- “Adolescent Cooking Abilites and Behaviors: Associations With Nutrition and Emotional Well-Being” (a journal article announcing new research findings)

- Wikipedia articles

See footnote for answers

The Details Are Tricky— A few things about primary or secondary sources might surprise you:

- Sources become primary rather than always exiting as primary sources.

It’s easy to think that it is the format of primary sources that makes them primary. But that’s not all that matters. So when you see lists like the one above of sources that are often used as primary sources, it’s wise to remember that the ones listed are not automatically already primary sources. Firsthand sources get that designation only when researchers actually find their information relevant and use it.

Example

- Primary sources, even eyewitness accounts, are not necessarily accurate. Their accuracy has to be evaluated, just like that of all sources.

- Something that is usually considered a secondary source can be considered a primary source, depending on the research project.

Example

- Deciding whether to consider a journal article a primary or a secondary source can be complicated for at least two reasons.

First, journal articles that report new research for the first time are usually based on data. So some disciplines consider the data to be the primary source, and the journal article that describes and analyzes them is considered a secondary source.

However, particularly in the sciences, the original researcher might find it difficult or impossible (he or she might not be allowed) to share the data. So sometimes you have nothing more firsthand than the journal article, which argues for calling it the relevant primary source because it’s the closest thing that exists to the data.

Second, even journal articles that announce new research for the first time usually contain more than data. They also typically contain secondary source elements, such as a literature review, bibliography, and sections on data analysis and interpretation. So they can actually be a mix of primary and secondary elements. Even so, in some disciplines, a journal article that announces new research findings for the first time is considered to be, as a whole, a primary source for the researchers using it.

Activity: Under What Circumstances?

Instructions: Look at each of the sources listed below and think of circumstances under which each could become a primary source. (There are probably many potential circumstances for each.) So, just imagine you are a researcher with projects that would make each item firsthand information that is relevant to your work. What could a project be about that would make each source relevant firsthand information?[7]

- A marriage license.

- Poet W.H. Auden’s elegy for Y.S. Yeats.

- An arrowhead made by (Floriday) Seminole Native Americans but found at Flint Ridge outside Columbus, Ohio.

- E-mail between the Canadian ambassador to the United States, Kirsten Hillman, and her staff about the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA).

See footnote for possible answers

Despite their trickiness, what primary sources usually offer is too good not to consider using because:

- They are original. This unfiltered, firsthand information is not available anywhere else.

- Their creator was a type of person unlike others in your research project, and you want to include that perspective.

- Their creator was present at an event and shares an eyewitness account.

- They are objects that existed at the particular time your project is studying.

Particularly in humanities courses, your professor may require you to use a certain number of primary sources for your project. In other courses, particularly in the sciences, you may be required to use only primary sources.

Popular, Professional, and Scholarly

We can also categorize information by the expertise of its intended audience. Considering the intended audience—how much of an expert one has to be to understand the information—can indicate whether the source has sufficient credibility and thoroughness to meet your need.

There are varying degrees of expertise:

Popular – Popular newspaper and magazine articles (such as articles from The New York Times, Time, and The Washington Post) are meant for a large general audience, are generally affordable, and are easy to purchase or available for free. They are written by staff writers or reporters for the general public.

Additionally, they are:

- About news, opinions, background information, and entertainment.

- More attractive than scholarly journals, with catchy titles, attractive artwork, and many advertisements but no footnotes or references.

- Published by commercial publishers.

- Published after approval from an editor.

- For information on using news articles as sources (from newspapers in print and online, broadcast news outlets, news aggregators, news databases, news feeds, social media, blogs, and citizen journalism).

See 2.3 “Understanding Sources” for more details.

Professional – Professional magazine articles (such as Plastic Surgical Nursing and Music Teacher) are meant for people in a particular profession and are often accessible through a professional organization. Staff writers or other professionals in the targeted field write these articles at a level and with the language to be understood by everyone in the profession.

Additionally, they are:

- About trends and news from the targeted field, book reviews, and case studies.

- Often less than 10 pages, some of which may contain footnotes and references.

- Usually published by professional associations and commercial publishers.

- Published after approval from an editor.

Scholarly – Scholarly journal articles (such as Plant Science and Education and Child Psychology) are meant for scholars, students, and the general public who want a deep understanding of a problem or issue. Researchers and scholars write these articles to present new knowledge and further understanding of their field of study.

Additionally, they are:

- Where findings of research projects, data and analytics, and case studies usually appear first.

- Often long (usually over 10 pages) and always include footnotes and references.

- Usually published by universities, professional associations, and commercial publishers.

- Published after approval by peer review or from the journal’s editor.

See 2.3 “Understanding Sources” for more detail.

Sometimes it is difficult to understand or conceptualize how sources can vary simply depending on what audience they were written for. The following links will connect you with supplemental tools, guides, and explanations that hopefully will help fill in any gaps regarding popular vs. scholarly sources.

Media Attributions

- Lindsey MacCallum and Teaching & Learning Ohio State University Libraries

- Ibid.

- Ibid.

- Ibid.

- Ibid.

- Ibid.

- 2.2 (except where otherwise noted) was borrowed with minor edits and additions from Choosing & Using Sources: A Guide to Academic Research, 1st Canadian Edition by Lindsey MacCallum and Teaching & Learning Ohio State University Libraries which is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License ↵

- In some cases, you will have more options than you are physically able to read in a span of a semester. ↵

- Quantitative: age, weight, GPA, income Qualitative: race, gender, class (freshman, sophomore, etc.), major. Are there others? ↵

- A photo of each secretary-general, The flag of their country of origin, and A world map with their country of origin shaded. Are there others? ↵

- This is especially true if your audience is composed of those who are a part of academia or the subject field you are positing your argument within. ↵

- 1. tertiary; 2. primary; 3. tertiary; 4. tertiary; 5. secondary; 6. primary; 7. tertiary ↵

- a. You are writing about the life of a person who claimed to have married several times, and you need more than just her statements about when those marriages took place and to whom; b. Your research project is about the Auden-Yeats relationship; c. Your research project is about trade among 19th-century Indigenous peoples east of the Mississippi River. d. Your research project is on how Ambassador Hillman conveyed a decision about NAFTA negotiations to her staff. ↵