Chapter 11: Toward the Present

Chapter Introduction & Learning Objectives

One of the definitive transformations in global politics after World War II was the shift in the locus of power from Europe to the United States and the Soviet Union. It was American aid or Soviet power that guided the reconstruction of Europe after the war, and both superpowers proved themselves more than capable of making policy decisions for the countries within their respective spheres of influence. The Soviets directly controlled Eastern Europe and had an enormous amount of influence in the other communist countries, while the United States exercised considerable influence on the member nations of NATO.

In 1991 the Soviet Union collapsed. Like the proverbial sorcerer’s apprentice who unleashed an enchantment he cannot control, the (last, as it turned out) Soviet premier Mikhail Gorbachev had begun a series of reforms in 1986 that ultimately resulted in the dismantling of the Soviet state. In 1989, the communist regimes of the Eastern Bloc crumbled as it became clear that the USSR would not intervene militarily to prop them up as it had in the past. Nationalist independence movements exploded across the USSR and, finally, the entire system fell apart to be replaced by sovereign nations. In 1991, Russia itself reemerged as a distinct country in the process rather than just the most powerful part of a larger union.

In 1992, following the Soviet collapse, the American political theorist Francis Fukuyama published a book entitled The End of History and the Last Man. Put briefly,The End of History’s central argument is that humanity was entering into a new stage in which the essential political and economic questions of the past had been resolved. Henceforth, market capitalism and liberal democracy would be conjoined in a symbiotic relationship. Human rights would be guaranteed by the political system that also provided the legal framework for a prosperous capitalist economy. All of the alternatives had already been tried and failed, after all, from the old order of monarchy and nobility to modern fascism and, as of 1991, Soviet communism. Thus, former dictatorships would (if they had not already) join the fold of American-style democracy and capitalism soon enough.

As it turned out, Fukuyama’s predictions were true for some of the former members of the Eastern Bloc: East and West Germany were reunited, and the countries of Eastern Europe in general, from Romania to newly-independent and separate Slovakia and the Czech Republic, elected democratic governments and sought to join the capitalist western economies. So, too, did Russia initially, although almost immediately its economy foundered in the face of the “shock therapy” led by western advisors: the rapid imposition of a market economy and the dismantling of the social safety net that had been the one meaningful benefit of the former Soviet system for ordinary citizens.

In the long run, however, countries all over the globe in the post-Soviet era were as likely to embrace an economic and political system unanticipated by Fukuyama in 1992: authoritarian capitalism. To the surprise of many at the time, there is nothing about market economics that requires a democratic government. So long as an authoritarian state was willing to oversee the legal framework, and occasional economic interventions, necessary for capitalism to function, a capitalist economy could thrive despite the absence of civil and political rights. This pattern was (and remains) true even of those states that remain nominally “communist,” the People’s Republic of China most importantly. Likewise, starting with the election of Vladimir Putin in 2000, Russia would soon adopt the model of authoritarian capitalism, with a single political party controlling the state and exercising enormous influence, if not outright control, of the press. Meanwhile, in the countries of Central and Western Europe in which battles over economics and politics had finally been resolved in favor of the democracy/capitalism hybrid in the postwar era, social and cultural problems developed by the 1970s that remain largely unresolved in the present.

The End of the Postwar Compromise

Contemporary Europe struggles with the legacies of the postwar era. The incredible economic boom of the postwar decades came to a screeching halt in the early 1970s, when OPEC, the international consortium of oil-producing nations, instituted an embargo of oil in protest of western support of Israel in the Yom Kippur War of 1973. Gas prices skyrocketed, and the incredible economic growth of the postwar era simply stopped, never to regain the momentum it had from 1945 – 1973. Those critical decades of the baby boom and economic boom had left their mark in several ways, however, resulting in social democracy, large immigrant populations, and high standards of living. Contemporary European politics have grappled with each of those factors in turn.

Politically and socially, one of the most difficult legacies of the postwar years has been immigration. While racism was always a factor in Europe, during the boom years immigrants were generally regarded as at the very least “useful” for European countries and their economies. They did the jobs that Europeans did not want and formed a vital part of the economy of Western Europe as a whole. When the economic boom ended, however, they were rapidly castigated for their supposed laziness, penchant for criminality, and failure to assimilate – in a word, they were the scapegoats for everything going wrong with economics and social issues in the post-boom era. Thus, the far right in Europe was reborn, a generation after the defeat of fascism, in the form of harshly anti-immigrant political parties, often with a smattering of fascistic and anti-Semitic rhetoric mixed in (France’s National Front was the first, and remains a powerful force in French politics).

The new European far right called for extremely limited quotas for immigration, laws banning the expression of non-Christian religious traditions (most importantly, those associated with Islam), and a broader cultural shift rejecting the tolerance and cosmopolitanism of mainstream European culture after the war. They also attacked non-white citizens of European countries, citizens born in Europe to immigrant parents. In other words, citizens of immigrant ancestry were legally the same as any other citizen, but the far right capitalized on a latent racist definition of British or French or Swiss or German, as white. This racially-based definition and understanding of European identity was simply factually wrong by the 1960s and 1970s: there were hundreds of thousands of Europeans of color who had been born and raised in the countries to which their parents or grandparents had immigrated, but it remained the basis of the appeal of far right politics to millions of white Europeans.

While the far right has gained strength in many European countries over time, of greater overall impact was the changed identity of mainstream center-right conservatism. This form of conservatism is often called “neoconservatism” to differentiate it from the earlier form of postwar center-right politics. By far the most important change within neo-conservatism was that the center-right belatedly came to reject the welfare state. The compromise between left and right that had seen a broad endorsement of nationalized industry, free health care and education, subsidies for housing, and strong unions definitively collapsed starting in the mid-1970s. Neoconservatives blamed the welfare state and unions for exacerbating the economic crisis of the 1970s, arguing that the state was always inefficient and bloated compared to private industry, and they promised to do away with unneeded and counterproductive regulation in favor of unchecked market exchange.

The iconic neo-conservative politician was the British Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher, who held office from 1979 to 1990. Thatcher acquired the nickname “the Iron Lady” for her blunt manner of speaking and her refusal to compromise. While prime minister, Thatcher privatized a number of industries in Britain, most importantly the railways. She took a hard line with unions, shutting down northern English coal mines rather than giving in to the demands of the coal miners’ union (the English mining industry simply shut down as a result – it has never recovered). She slashed government subsidies for various industries, resulting in an explosion of unemployment in manufacturing areas.

The sectors of the British economy that benefited from Thatcherite policies were financial in nature: banks in particular thrived as regulations were dropped and banks were legally allowed to pursue vast profits through financial speculation. Britain began its transition toward what it is in the present: the dynamic, wealthy financial and commercial center that is London surrounded by an economically stagnant and often politically resentful nation. Thatcher herself was a polarizing figure in British society – while she was reviled by her opponents, millions of Britons adored her for her British pride, her hard-nosed refusal to compromise, and her unapologetic, Social Darwinist contempt for the poor – she once advised the English that they ought to “glory in inequality” because it was symptomatic of the strong and smart succeeding.

The British economy began to recover as a whole in the early 1980s, but the major reason that Thatcher stayed in power was her success in selling an image of strength and trenchant opposition to British unions, which had reached the height of their influence in the mid-1970s. A brief war over the (strategically and economically unimportant) Falkland Islands in the Pacific between Argentina and Britain in 1982 also buoyed her popularity with patriotic citizens. Finally, the British Labour party was in disarray, split between its still genuinely socialist left wing and a new more moderate reform movement that wanted to abandon socialist rhetoric in favor of straightforward liberalism. Thus, Thatcher remained in power until 1990, when her own party decided she was no longer palatable to the electorate and replaced her with a somewhat forgettable English politician named John Major.

Outside of Britain, the essential characteristics of Western European politics were in place by the 1980s that remain to this day. Center-right parties from Italy to Germany and from France to Britain correspond to the Thatcherite neo-conservative model, embracing the free market and trying to limit the extent of the welfare state (although none of these parties advocate getting rid of the welfare state entirely; generations of Europeans, including people who vote for center right parties, expect free health care, education, and social benefits). Most center-right parties outside of Britain have been less willing to truly gut the welfare state than was Thatcher and her conservatives, but the general focus on the market remains their defining characteristic overall.

On the other side of the political spectrum, the major change within left-wing parties was the final and definitive abandonment of Marxist ideology. Again, Britain provides the iconic example: the triumph within the Labour Party of a centrist faction that created “New Labour,” a political philosophy that supports the welfare state but also accepts the position that the free market is the essential motor of economic growth. The iconic figure of New Labour was the prime minister Tony Blair, who held office from 1997 – 2007. Even in countries whose major leftist parties had the word “socialist” in their titles – France’s Socialist Party, for example – the whole notion of revolution was gone by the 1990s. Instead, the center-left parties came to be the custodians of the welfare state while belatedly joining the center-right in favoring market economics in the private sector.

Broadly speaking, the defining argument between mainstream leftist and mainstream rightist parties leading up to the present is about how much free market deregulation to embrace. Many Europeans have become attracted to the far-right parties mentioned above as much because the two sides of mainstream politics are almost indistinguishable; to many Europeans, the far-right seems like the only “real” alternative. In turn, with revolution off the agenda, the far left in Europe is represented now by the Green parties. Green parties (the strongest of which is Germany’s) are very strong supporters of environmental legislation and are the most hostile to free market deregulation of any political faction, but they remain limited in their electoral impact.

Eastern Europe

While the politics and economics of Western Europe underwent a number of changes in the decades following World War II, they nevertheless represent an essential continuity (i.e. market economies, welfare states, democratic politics) in many ways right up to the present. The opposite is true of Eastern Europe: while the postwar order of command economy communism and single-party, authoritarian rule held true almost through the 1980s, that entire system imploded in the end, with lasting consequences for the region and for the world.

As of the 1970s, the economic stagnation of the east was far worse than that of the west. Real growth rates were lost in a haze of fudged statistics, and technology had failed to keep up with western standards. By the 1980s the only profitable industries in Russia were oil and vodka, and then oil prices began a decade-long decline. Politically, Eastern European governments were so corrupt that it was basically pointless to distinguish between normal “politics” and “corruption” – every political decision was governed by personal networks of corrupt politicians who traded political favors and controlled access to creature comforts (like the coveted

dachas – vacation cottages – in the USSR). The USSR’s politburo, the apex of political power in which decisions of real consequence were made, was staffed by aging apparatchiks who had spent their entire lives working within this system.

Then, the old men of the order simply started dying off. Brezhnev died in 1982, then the next two leaders of the Soviet communist party died one after the other in 1984 and 1985. Mikhail Gorbachev, who took power in 1985, was a full generation younger, and he brought with him a profoundly different outlook on the best path forward for the USSR and its “allies.” Unlike the men of the older generation, Gorbachev was convinced that the status quo was increasingly untenable – the Soviet economy staggered along with meager or no growth, the entire educational system was predicated on propaganda masquerading as fact, and the state could barely keep up its spending on the arms race with the United States (especially after the American president Ronald Reagan came to office in 1980 and poured resources into the American military).

Gorbachev was convinced that the only way for the Soviet system to survive was through real, meaningful reforms – the kinds flirted with by Khrushchev in the 1950s but swiftly abandoned. To that end, Gorbachev introduced two reformist state policies: Glasnost and Perestroika. Glasnost means “openness” or “transparency” in information. It represented the relaxation of censorship within the Soviet system, one that was most dramatically demonstrated in 1986 when Gorbachev allowed an accurate appraisal in the press of a horrific nuclear accident at the Chernobyl nuclear plant. The idea behind Glasnost was to allow frank and honest discussion, to end the ban on truth, in an effort to win back the hearts and minds of Soviet people to their own government and social system.

Simultaneously, Gorbachev introduced Perestroika, meaning “restructuring.” This program was meant to reform the economy, mostly by modernizing industry and allowing limited market exchange. The two policies – openness and restructuring – were meant to work in tandem to improve the economy and create a dynamic, truthful political and social system. What Gorbachev had not anticipated, however, was that once Soviet citizens realized that they could publish views critical of the state, an explosion of pent-up anger and resentment swept across Soviet society. From merely reforming the structures of Soviet society, Glasnost in particular led to open calls to move away from Marxism-Leninism as the state’s official doctrine, for truly free and democratic elections, and for the national minorities to be able to assert their independence.

Meanwhile, the Soviet economy continued to spiral downwards. Soviet finances were in such disarray by the second half of the 1980s that Gorbachev simply ended the arms race with the United States, conceding the USSR could not match the US’s gigantic arsenal. Starting cautiously in 1988, he also announced to the governments of Eastern Europe that they would be “allowed to go their own way” without Soviet interference. Never again would columns of tanks respond to protests against communism. This development caused considerable dismay to hard-line Communist leaders in countries like East Germany, where the threat of Soviet intervention had always been the bulwark against the threat of reform. When Gorbachev made good on his promises and protest movements against the communist states started to grow, it was the beginning of the end for the entire Soviet Bloc.

The result was a landslide of change across Eastern Europe. Over the course of 1989, one country after another held free elections and communists were expelled from governments. Rapidly, new constitutions were drawn up. The Berlin Wall fell in November of 1989 and Germany was reunified less than a year later. Likewise, the USSR itself fell apart by 1991, torn apart by nationalist movements within its borders as Latvians, Lithuanians, Ukrainians, Kazakhs, and other national minorities of the USSR demanded their independence from Russian dominance. An attempted counter-revolution led by Soviet hardliners failed in the face of mass protest in Moscow, and the first free elections since the February Revolution of 1917 were held in Russia.

Since the collapse of the USSR, some Eastern European countries (e.g. the Czech Republic, Poland) have enjoyed at least some success in modernizing their economies and keeping political corruption at bay. In Russia itself, the 1990s were an unmitigated economic and social disaster as the entire country tried to lurch into a market economy without the slightest bit of planning or oversight. Western consultants, generally associated with international banking firms, convinced Russian politicians in the infancy of its new democracy to institute “shock therapy,” dismantling social programs and government services. While foreign loans accompanied these steps, new industries did not suddenly materialize to fill the enormous gaps in the Russian economy that had been played by state agencies. Unemployment skyrocketed and the distinctions between legitimate business and illegal or extra-legal trade all but vanished.

The result was an economy that was often synonymous with the black market, gigantic and powerful organized crime syndicates, and the rise of a small number of “oligarchs” to stratospheric levels of wealth and power. One shocking statistic is that fewer than forty individuals controlled about 25% of the Russian economy by the late 1990s. Just as networks of contacts among the Soviet apparatchiks had once been the means of securing a job or accessing state resources, it now became imperative for regular Russian citizens to make connections with either the oligarch-controlled companies or organized crime organizations.

Stability only began to return because of a new political strongman. Vladimir Putin, a former agent of the Soviet secret police force (the KGB), was elected president of Russia in 2000. Since that time, Putin has proved a brilliant political strategist, playing on anti-western resentment and Russian nationalism to buoy popular support for his regime, run by “his” political party, United Russia. While opposition political parties are not illegal, and indeed consistently try to make headway in elections, United Russia has been in firm control of the entire Russian political apparatus since shortly after Putin’s election. Opposition figures are regularly harassed or imprisoned, and many opposition figures have also been murdered (although the state itself maintains a plausible deniability in cases of outright assassination). Some of the most egregious excesses of the oligarchs of the 1990s were also reined in, while some oligarchs were instead incorporated into the United Russia power structure.

Unlike many of the authoritarian rulers of Russia in the past, Putin was (and remains) hugely popular among Russians. Media control has played a large part in that popularity, of course, but much of Putin’s popularity is also tied to the wealth that flooded into Russia after 2000 as oil prices rose. While most of that wealth went to enrich the existing Russian elites (along with some of Putin’s personal friends, who made fortunes in businesses tied to the state), it also served as a source of pride for many Russians who saw little direct benefit. Further boosts to his popularity came from Russia’s invasion of the small republic of Georgia in 2008 and, especially, its invasion and subsequent annexation of the Crimean Peninsula from the Ukraine in 2014. While the latter prompted western sanctions and protests, it was successful in supporting Putin’s power in Russia itself.

The European Union

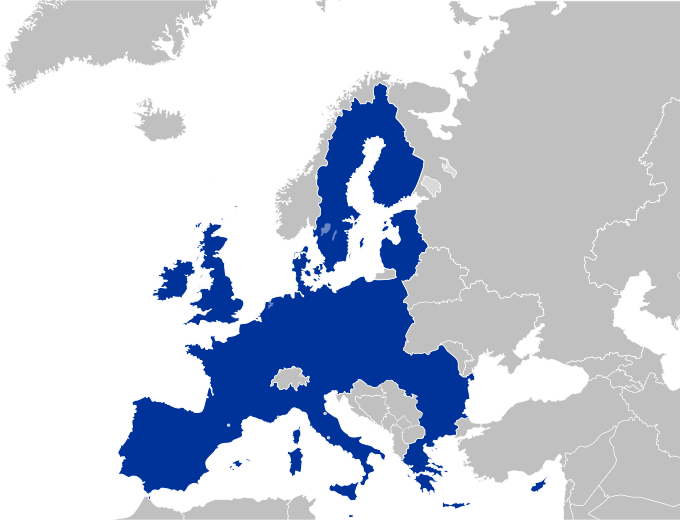

At the start of the postwar boom, most of the nations of western Europe entered into various international groups that sought to improve economic relations and trade between the member nations. Those culminated in the creation of the European Community (EC) in 1967, essentially an economic alliance and trade zone between most of the nations of non-communist Europe. Despite various setbacks, not the least the enmity between French and British politicians that achieved almost comic levels at times, the EC steadily added new members into the 1980s. Its leadership also began to discuss the possibility of moving toward an even more inclusive model for Europe, one in which not just trade but currency, law, and policy might be more closely aligned between countries. That vision of a united Europe was originally conceived in large part in hopes of creating a power-bloc to rival the two superpowers of the Cold War, but it also encompassed a moral vision of an advanced, rational economic and political system, in contrast to the conflicts that had so often characterized Europe in the past.

The EC officially became the European Union in 1993, and various member nations of the former EC voted (sometimes barely) to join in the following years. Over time, passport controls at borders between the member states of the EU were eliminated entirely. The member nations agreed to policies meant to ensure civil rights throughout the Union, as well as economic stipulations (e.g. limitations on national debt) meant to foster overall prosperity. Most spectacularly, at the start of 2002, the Euro became the official currency of the entire EU except for Great Britain, which clung tenaciously to the venerable British Pound.

The period between 2002 and 2008 was one of relative success for the architects of the EU. The economies of Eastern European countries in particular accelerated, along with a few unexpected western countries like Ireland (called the “Celtic Tiger” at the time for its success in bringing in outside investment by slashing corporate tax rates). Loans from wealthier members to poorer ones, the latter generally clustered along the Mediterranean, meant that none of the countries of the “Eurozone” lagged too far behind. While the end of passport controls at borders worried some, there was no general immigration crisis to speak of.

Unfortunately, especially since the financial crisis of 2008, the EU has been fraught with economic problems. The major issue is that the member nations cannot control their own economies past a certain point – they cannot devalue currency to deal with inflation, they are nominally prevented from allowing their own national debts to exceed a certain level of their Gross Domestic Product (3%, at least in theory), and so on. The result is that it is terrifically difficult for countries with weaker economies such as Spain, Italy, or Greece, to maintain or restore economic stability. Instead, Germany ended up serving as the EU’s banker and also its inadvertent political overlord, issuing loan after loan to other EU states while dictating economic and even political policy to them. This led to the surprising success of far-left political parties like Greece’s Syriza, which rose to power by promising to buck German demands for austerity and by threatening to leave the Eurozone altogether (it later backpedaled, however).

In the most shocking development to undermine the coherence and stability of the EU as a whole, Great Britain narrowly voted to leave the Union entirely in 2016. In what analysts largely interpreted as a protest vote against not just the EU itself, but of complacent British politicians whose interests seemed squarely focused on London’s welfare over that of the rest of the country, a slim majority of Britons voted to end their country’s membership in the Union. Years of bitter political struggle ensued, but the country finally left in early 2020. The political and economic consequences remain unclear: the British economy has been deeply enmeshed with that of the EU nations since the end of World War II, and it is simply unknown what effect its “Brexit” will have in the long run.

The Middle East

The Middle East has been one of the most conflicted regions in the world in the last century, following the collapse of the Ottoman Empire in World War I. In the recent past, much of that instability has revolved around three interrelated factors: the Middle East’s role in global politics, the Israeli-Palestinian conflict, and the vast oil reserves of the region. In turn, the United States played an outsize role in shaping the region’s politics and conflicts.

During the Cold War the Middle East was constantly implicated in American policies directed to curtail the (often imaginary) threat of Soviet expansion. The US government tended to support political regimes that could serve as reliable clients regardless of the political orientation of the regime in question or that regime’s relationship with its neighbors. First and foremost, the US drew close to Israel because of Israel’s antipathy to the Soviet Union and its own powerful military. Israel’s crushing victory in the 1967 Six-Day War demonstrated to American politicians that it was a powerhouse worth cultivating, and in the decades that followed the governing assumption of American – Israeli relations was that Israel was the most reliable powerful partner supporting American interests. Part of that sympathy was also born out of respect for the fact that Israel’s government is democratic and that it has a thriving civil society.

Simultaneously, however, the US supported Arab and Persian regimes that were anything but democratic. The Iranian regime under the Pahlavi dynasty was restored to power through an American-sponsored coup in 1953, with the democratically-elected prime minister Muhammad Mosaddegh expelled from office. The Iranian Shah Muhammad Reza Pahlavi ruled Iran as a loyal American client for the next 26 years while suppressing dissent through a brutal secret police force. The Iranian regime purchased enormous quantities of American arms (50% of American arms sales were to Iran in the mid-1970s) and kept the oil flowing to the global market. Iranian society was highly educated and its economy thrived, but its government was an oppressive autocracy.

Likewise, the equally autocratic monarchy of Saudi Arabia emerged as the third “pillar” in the US’s Middle Eastern clientage system. Despite its religious policy being based on Wahhabism, the most puritanical and rigid interpretation of Islam in the Sunni world, Saudi Arabia was welcomed by American policitians as another useful foothold in the region that happened to produce a vast quantity of oil. Clearly, opposition to Soviet communism and access to oil proved far more important from a US policy perspective than did the lack of representative government or civil rights among its clients.

This status quo was torn apart in 1979 by the Iranian Revolution. What began as a coalition of intellectuals, students, workers, and clerics opposed to the oppressive regime of the Shah was overtaken by the most fanatical branch of the Iranian Shia clergy under the leadership of the Ayatollah (“eye of God”) Ruhollah Khomeini. When the dust settled from the revolution, the Ayatollah had become the official head of state and Iran had become a hybrid democratic-theological nation: the Islamic Republic of Iran. The new government featured an elected parliament and equality before the law (significantly, women enjoy full political rights in Iran, unlike in some other Middle Eastern nations like Saudi Arabia), but the Ayatollah had final say in directing politics, intervening when he felt that Shia principles were threatened. Deep-seated resentment among Iranians toward the US for the latter’s long support of the Shah’s regime became official policy in the new state, and in turn the US was swift to vilify the new regime.

The 1980s and 1990s saw a botched Israeli invasion of Lebanon, an ongoing military debacle for the Sovet Union in Afghanistan, and a full-scale war between the new Islamic Republic of Iran and its neighbor, Iraq. Ruled by a secular nationalist faction, the Ba’ath Party, since 1968, Iraq represented yet another form of autocracy in the region. Saddam Hussein, The military leader at the head of the Ba’ath Party, launched the Iran-Iraq War as a straightforward territorial grab. The United States supported

both sides during the war at different points despite its avowed opposition to the Iranian regime. In the end, the war sputtered to a bloody stalemate in 1988 after over a million people had lost their lives.

Just two years later, Iraq invaded the neighboring country of Kuwait and the United States (fearing the threat to oil supplies and now regarding Hussein’s regime as dangerously unpredictable) led a coalition of United Nations forces to expel it. The subsequent Gulf War was an easy victory for the US and its allies, even as the USSR spiralled toward its messy demise as communism collapsed in Eastern Europe. The early 1990s thus saw the United States in a position of unparalleled power and influence in the Middle East, with every country either its client and ally (e.g. Saudi Arabia, Israel) or hostile but impotent to threaten US interests (e.g. Iran, Iraq). American elites subscribed to what President George Bush described as the “New World Order”: America would henceforth be the world’s policeman, overseeing a global market economy and holding rogue states in check with the vast strength of American military power.

Instead, the world was shocked when fundamentalist Muslim terrorists, not agents of a nation, hijacked and crashed airliners into the World Trade Center towers in New York City and into the Pentagon (the headquarters of the American military) on September 11, 2001. Fueled by hatred toward the US for its ongoing support of Israel against the Palestinian demand for sovereignty and for the decades of US meddling in Middle Eastern politics, the terrorist group Al Qaeda succeeded in the most audacious and destructive terrorist attacks in modern history. President George W. Bush (son of the first President Bush) vowed a global “War on Terror” that has, almost two decades later, no apparent end in sight. The American military swiftly invaded Afghanistan, ruled by an extremist Sunni Muslim faction known as the Taliban, for sheltering Al Qaeda. American forces easily toppled the Taliban but failed to destroy it or Al Qaeda.

In a fateful decision with continuing reverberations in the present, the W. Bush presidency used the War on Terror as an excuse to settle “unfinished business” in Iraq as well. Despite the complete lack of ties between Hussein’s regime and Al Qaeda, and despite the absence of the “weapons of mass destruction” used as the official excuse for war, the US launched a full scale invasion in 2002 to topple Hussein. That much was easily accomplished, as once again the Iraqi military proved completely unable to hold back American forces. Within months, however, Iraq devolved into a state of murderous anarchy as former leaders of the Ba’ath Party (thrown out of office by American forces), local Islamic clerics, and members of different tribal or ethnic groups led rival insurgencies against both the occupying American military and their own Iraqi rivals. The Iraq War thus became a costly military occupation rather than an easy regime change, and in the following years the internecine violence and American attempts to suppress Iraqi insurgents led to well over a million deaths (estimates are notoriously difficult to verify, but the death toll might actually be over two million). A 2018 US Army analysis of the war glumly concluded that the closest thing to a winner to emerge from the Iraq War was, ironically, Iran, which used the anarchic aftermath of the invasion to exert tremendous influence in the region.

Toward the Present

While Europe has suffered from economic and, to a lesser extent, political instability since the 1980s, that instability pales in comparison to the instability of other world regions. In particular, the Middle East entered into a period of outright bloodshed and chaos as the twenty-first century began. In turn, the shock waves of Middle Eastern conflict have reverberated around the globe, inspiring the growth of international terrorist groups on the one hand and racist and Islamophobic political parties on the other.

To cite just the most important examples, the US invasion of Iraq in 2002 inadvertently prompted a massive increase in recruitment for anti-western terrorist organizations (many of which drew from disaffected EU citizens of Middle Eastern and North African ancestry). The Arab Spring of 2010 led to a brief moment of hope that new democracies might take the place of military dictatorships in countries like Libya, Egypt, and Syria, only to see authoritarian regimes or parties reassert control. Syria in particular spiraled into a horrendously bloody civil war in 2010, prompting millions of Syrian civilians to flee the country. Turkey, one of the most venerable democracies in the region since its foundation as a modern state in the aftermath of World War I, has seen its president Recep Tayyip Erdoğan steadily assert greater authority over the press and the judiciary. The two other regional powers, Iran and Saudi Arabia, carry on a proxy war in Yemen and fund rival paramilitary (often considered terrorist) groups across the region. Israel, meanwhile, continues to face both regional hostility and internal threats from desperate Palestinian insurgents, responding by tightening its control over the nominally autonomous Palestinian regions of the West Bank and Gaza Strip.

In Europe, fleeing Middle Eastern (and to a lesser extent, African) refugees seeking the infinitely greater stability and opportunity available to them abroad have brought about a resurgence of far-right and, in many cases, openly neo-fascist politics. While fascistic parties like France’s National Front have existed since the 1960s, they remained basically marginal and demonized for most of their history. Since 2010, far right parties have grown steadily in importance, seeing their share of each country’s electorate increase as worries about the impact of immigration drives voters to embrace nativist, crypto-racist political messages. Even some citizens who do not harbor openly racist views have come to be attracted to the new right, since mainstream political parties often seem to represent only the interests of out-of-touch social elites (again, Brexit serves as the starkest demonstration of voter resentment translating into a shocking political result).

While interpretations of events since the start of the twenty-first century will necessarily vary, what seems clear is that both the postwar consensus between center-left and center-right politics is all but a dead letter. Likewise, fascism can no longer be considered a terrible historical error that is, fortunately, now dead and gone; it has lurched back onto the world stage. A widespread sense of anger, disillusionment, and resentment haunts politics not just in Europe, but in much of the world.

That being noted, there are also indications that the center still holds. In France, the National Front’s presidential candidate in 2017, Marine Le Pen, was decisively defeated by the resolutely centrist Emmanuel Macron. Contemporary far-right parties have yet to enjoy the kind of electoral breakthrough that set the stage for (to cite one obvious example) the Nazi seizure of power in 1933. Even those countries that have proved most willing to use military force in the name of their ideological and economic agendas, namely Russia and the United States, have not launched further wars on the scale of the disastrous American invasion of Iraq in 2002.

Predicting the future is a fool’s errand, and one that historians in particular are generally loathe to engage in. That said, if nothing else, history provides both examples and counterexamples of things that have happened in the past that can, and should, serve as warnings for the present. As this text has demonstrated, much of history has been governed by greed, indifference to human suffering, and the lust for power. It can be hoped that studying the consequences of those factors and the actions inspired by them might prove to be an antidote to their appeal, and hopefully to their purported legitimacy as political motivations.

Image Citations (Wikimedia Commons):

Margaret Thatcher – Public Domain

Mikhail Gorbachev – Creative Commons, RIA Novosti

EU Map – Creative Commons, CrazyPhunk