Chapter 7: American Expansion in the West

Chapter Introduction & Learning Objectives

While a small number of settlers had pushed westward before the mid-nineteenth century, the land west of the Mississippi was largely unexplored by the United States. Most Americans, if they thought of it at all, viewed this territory as an arid wasteland suitable only for American Indians. The reflections of early explorers who conducted scientific treks throughout the West tended to confirm this belief. Major Stephen Harriman Long, who commanded an expedition through Missouri and into the Yellowstone region in 1819–1820, frequently described the Great Plains as an arid and useless region, suitable as nothing more than a “great American desert.” But, beginning in the 1840s, a combination of economic opportunity and ideological encouragement changed the way Americans thought of the West. The federal government offered a number of incentives, making it viable for Americans to take on the challenge of seizing these rough lands from their Native American and Hispanic owners. Still, most Americans who went west needed some financial security at the outset of their journey; even with government aid, the truly poor could not make the trip. The cost of moving an entire family westward, combined with the risks as well as the questionable chances of success, made the move prohibitive for most. While the economic Panic of 1837 led many to question the promise of urban America, and thus turn their focus to the promise of commercial farming in the West, the Panic also resulted in many lacking the financial resources to make such a commitment. For most, the dream to “Go west, young man” remained unfulfilled.

While much of the basis for westward expansion was economic, there was also a more philosophical reason, which was bound up in the American belief that the country—and the Indigenous peoples who populated it—were destined to come under the civilizing rule of Euro-American settlers and their superior technology, most notably railroads and the telegraph. While the extent to which that belief was a heartfelt motivation held by most Americans, or simply a rationalization of the conquests that followed, remains debatable, the clashes—both physical and cultural—that followed this western migration left scars on the country that are still felt today.

At the completion of reading the chapter, the student will be able to:

- Explain the evolution of American views about westward migration in the mid-nineteenth century

- Analyze the ways in which the federal government facilitated Americans’ westward migration in the mid-nineteenth century

MANIFEST DESTINY

The concept of Manifest Destiny found its roots in the long-standing traditions of territorial expansion upon which the nation itself was founded. This phrase, which implies divine encouragement for territorial expansion, was coined by magazine editor John O’Sullivan in 1845, when he wrote in the United States Magazine and Democratic Review that “it was our manifest destiny to overspread the continent allotted byProvidence for the free development of our multiplying millions.” Although the context of O’Sullivan’s original article was to encourage expansion into the newly acquired Texas territory, the spirit it invoked would subsequently be used to encourage westward settlement throughout the rest of the nineteenth century. Land developers, railroad magnates, and other investors capitalized on the notion to encourage westward settlement for their own financial benefit. Soon thereafter, the federal government encouraged this inclination as a means to further develop the West during the Civil War, especially at its outset, when concerns over the possible expansion of slavery deeper into western territories was a legitimate fear.

The idea was simple: Americans were destined—and indeed divinely ordained—to expand democratic institutions throughout the continent. As they spread their culture, thoughts, and customs, they would, in the process, expose the native inhabitants to Protestant institutions and, more importantly, new ways to develop the land. O’Sullivan may have coined the phrase, but the concept had preceded him: Throughout the 1800s, politicians and writers had stated the belief that the United States was destined to rule the continent.

O’Sullivan’s words, which resonated in the popular press, matched the economic and political goals of a federal government increasingly committed to expansion.

Manifest Destiny justified in Americans’ minds their right and duty to govern any other groups they encountered during their expansion, as well as absolved them of any questionable tactics they employed in the process. While the commonly held view of the day was of a relatively empty frontier, waiting for the arrival of the settlers who could properly exploit the vast resources for economic gain, the reality was quite different. Hispanic communities in the Southwest, diverse tribes throughout the western states, as well as other settlers from Asia and Western Europe already lived in many parts of the country. American expansion would necessitate a far more complex and involved exchange than simply filling empty space.

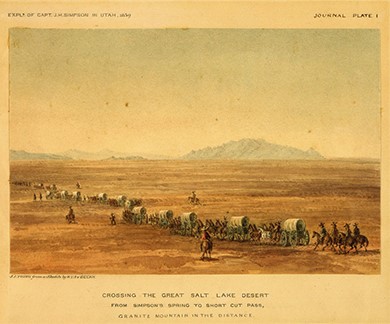

Still, in part as a result of the spark lit by O’Sullivan and others, waves of Americans and recently arrived immigrants began to move west in wagon trains. They travelled along several identifiable trails: first the Oregon Trail, then later the Santa Fe and California Trails, among others. The Oregon Trail is the most famous of these western routes. Two thousand miles long and barely passable on foot in the early nineteenth century, by the 1840s, wagon trains were a common sight. Between 1845 and 1870, considered to be the height of migration along the trail, over 400,000 settlers followed this path west from Missouri (Figure 17.3). Despite emphasis on conflict with Native Americans in movies, tribe members often served as guides or traded with the emigrants.

FIGURE Hundreds of thousands of people travelled west on the Oregon, California, and Santa Fe Trails, but their numbers did not ensure their safety. Illness, starvation, and other dangers—both real and imagined— made survival hard. But despite popular images of wagons circled to defend against Native American attacks, more Native people than emigrants died from the violence associated with the overland routes.(credit: U.S. National Archives and Records Administration)

|

DEFINING AMERICAN |

|

Who Will Set Limits to Our Onward March? “America is destined for better deeds. It is our unparalleled glory that we have no reminiscences of battle fields, but in defense [sic] of humanity, of the oppressed of all nations, of the rights of conscience, the rights of personal enfranchisement. Our annals describe no scenes of horrid carnage, where men were led on by hundreds of thousands to slay one another, dupes and victims to emperors, kings, nobles, demons in the human form called heroes. We have had patriots to defend our homes, our liberties, but no aspirants to crowns or thrones; nor have the American people ever suffered themselves to be led on by wicked ambition to depopulate the land, to spread desolation far and wide, that a human being might be placed on a seat of supremacy. . . .” “The expansive future is our arena, and for our history. We are entering on its untrodden space, with the truths of God in our minds, beneficent objects in our hearts, and with a clear conscience unsullied by the past. We are the nation of human progress, and who will, what can, set limits to our onward march? Providence is with us, and no earthly power can.” “—John O’Sullivan, 1839” Think about how this quotation resonated with different groups of Americans at the time. When looked at through today’s lens, the actions of the westward-moving settlers were fraught with brutality and racism. At the time, however, many settlers felt they were at the pinnacle of democracy, and that with no aristocracy or ancient history, America was a new world where anyone could succeed. Even then, consider how the phrase “anyone” was restricted by race, gender, and nationality. Also consider how the idea of “untrodden space” ignores specific groups of people. |

FEDERAL GOVERNMENT ASSISTANCE

To assist the settlers in their move westward and transform the migration from a trickle into a steady flow, Congress passed two significant pieces of legislation in 1862: the Homestead Act and the Pacific Railway Act. Born largely out of President Abraham Lincoln’s growing concern that a potential Union defeat in the early stages of the Civil War might result in the expansion of slavery westward, Lincoln hoped that such laws would encourage the expansion of a “free soil” mentality across the West.

The Homestead Act allowed any head of household, or individual over the age of twenty-one—including unmarried women—to receive a parcel of 160 acres for only a nominal filing fee. All that recipients were required to do in exchange was to “improve the land” within a period of five years of taking possession. The standards for improvement were minimal: Owners could clear a few acres, build small houses or barns, or maintain livestock. Under this act, the government transferred over 270 million acres of public domain land to private citizens.

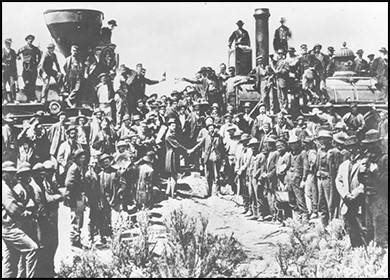

The Pacific Railway Act was pivotal in helping settlers move west more quickly, as well as move their farm products, and later cattle and mining deposits, back east. The first of many railway initiatives, this act commissioned the Union Pacific Railroad to build new track west from Omaha, Nebraska, while the Central Pacific Railroad moved east from Sacramento, California. The law provided each company with ownership of all public lands within two hundred feet on either side of the track laid, as well as additional land grants and payment through load bonds, prorated on the difficulty of the terrain it crossed. Because of these provisions, both companies made a significant profit, whether they were crossing hundreds of miles of open plains, or working their way through the Sierra Nevada Mountains of California. As a result, the nation’s first transcontinental railroad was completed when the two companies connected their tracks at Promontory, Utah, in the spring of 1869. Other tracks, including lines radiating from this original one, subsequently created a network that linked all corners of the nation (Figure 17.4).

FIGURE The “Golden Spike” connecting the country by rail was driven into the ground in Promontory, Utah, in 1869. The completion of the first transcontinental railroad dramatically changed the tenor of travel in the country, as people were able to complete in a week a route that had previously taken months.

In addition to legislation designed to facilitate western settlement, the U.S. government assumed an active role on the ground, building numerous forts throughout the West to aid settlers during their migration. Forts such as Fort Laramie in Wyoming (built in 1834) and Fort Apache in Arizona (1870) aimed to facilitate trade and limit conflict between migrants and local American Indian tribes. Others located throughout Colorado and Wyoming became important trading posts for miners and fur trappers. Those built in Kansas, Nebraska, and the Dakotas served primarily to provide relief for farmers during times of drought or related hardships. Forts constructed along the California coastline provided protection in the wake of the Mexican-American War as well as during the American Civil War. These locations subsequently serviced the U.S. Navy and provided important support for growing Pacific trade routes. Whether as army posts constructed to aid American migration, or as trading posts to further facilitate the development of the region, such forts proved to be vital contributions to westward migration.

WHO WERE THE SETTLERS?

In the nineteenth century, as today, it took money to relocate and start a new life. Due to the initial cost of relocation, land, and supplies, as well as months of preparing the soil, planting, and subsequent harvesting before any produce was ready for market, the original wave of western settlers along the Oregon Trail in the 1840s and 1850s consisted of moderately prosperous, White, native-born farming families of the East. But the passage of the Homestead Act and completion of the first transcontinental railroad meant that, by 1870, the possibility of western migration was opened to Americans of more modest means. What started as a trickle became a steady flow of migration that would last until the end of the century.

Nearly 400,000 settlers had made the trek westward by the height of the movement in 1870. The vast majority were men, although families also migrated, despite incredible hardships for women with young children. More recent immigrants also migrated west, with the largest numbers coming from Northern Europe and Canada. Germans, Scandinavians, and Irish were among the most common. These ethnic groups tended to settle close together, creating strong rural communities that mirrored the way of life they had left behind. According to U.S. Census Bureau records, the number of Scandinavians living in the United States during the second half of the nineteenth century exploded, from barely 18,000 in 1850 to over 1.1 million in 1900. During that same time period, the German-born population in the United States grew from 584,000 to nearly 2.7 million and the Irish-born population grew from 961,000 to 1.6 million. As they moved westward, several thousand immigrants established homesteads in the Midwest, primarily in Minnesota and Wisconsin, where, as of 1900, over one-third of the population was foreign-born, and in North Dakota, whose immigrant population stood at 45 percent at the turn of the century. Compared to European immigrants, those from China were much less numerous, but still significant. More than 200,000 Chinese arrived in California between 1876 and 1890, albeit for entirely different reasons related to the Gold Rush.

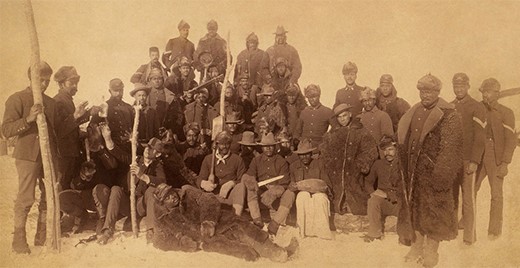

In addition to a significant European migration westward, several thousand African Americans migrated west following the Civil War, as much to escape the racism and violence of the Old South as to find new economic opportunities. They were known as exodusters, referencing the biblical flight from Egypt, because they fled the racism of the South, with most of them headed to Kansas from Kentucky, Tennessee, Louisiana, Mississippi, and Texas. Over twenty-five thousand exodusters arrived in Kansas in 1879–1880 alone. By 1890, over 500,000 Black people lived west of the Mississippi River. Although the majority of Black migrants became farmers, approximately twelve thousand worked as cowboys during the Texas cattle drives. Some also became “Buffalo Soldiers” in the wars against Native Americans. “Buffalo Soldiers” were African Americans allegedly so-named by various Native tribes who equated their black, curly hair with that of the buffalo. Many had served in the Union army in the Civil War and were now organized into six, all-Black cavalry and infantry units whose primary duties were to protect settlers during the westward migration and to assist in building the infrastructure required to support western settlement (Figure 17.5).

FIGURE “Buffalo Soldiers,” the first peacetime all-Black regiments in the U.S. Army, aided settlers, fought in the Indian Wars, and served as some of the country’s first national park rangers.

While White easterners, immigrants, and African Americans were moving west, several hundred thousand Hispanics had already settled in the American Southwest prior to the U.S. government seizing the land during its war with Mexico (1846–1848). The Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo, which ended the war in 1848, granted American citizenship to those who chose to stay in the United States, as the land switched from Mexican to U.S. ownership. Under the conditions of the treaty, Mexicans retained the right to their language, religion, and culture, as well as the property they held. As for citizenship, they could choose one of three options: 1) declare their intent to live in the United States but retain Mexican citizenship; 2) become U.S. citizens with all rights under the constitution; or 3) leave for Mexico. Despite such guarantees, within one generation, these new Hispanic American citizens found their culture under attack, and legal protection of their property all but non-existent.

VIOLENCE IN THE WILD WEST: MYTH AND REALITY

The popular image of the Wild West portrayed in books, television, and film has been one of violence and mayhem. The lure of quick riches through mining or driving cattle meant that much of the West did indeed consist of rough men living a rough life, although the violence was exaggerated and even glorified in the dime store novels of the day. The exploits of Wyatt Earp, Doc Holiday, and others made for good stories, but the reality was that western violence was more isolated than the stories might suggest. These clashes often occurred as people struggled for the scarce resources that could make or break their chance at riches, or as they dealt with the sudden wealth or poverty that prospecting provided.

Where sporadic violence did erupt, it was concentrated largely in mining towns or during range wars among large and small cattle ranchers. Some mining towns were indeed as rough as the popular stereotype. Men, money, liquor, and disappointment were a recipe for violence. Fights were frequent, deaths were commonplace, and frontier justice reigned. The notorious mining town of Bodie, California, had twenty-nine murders between 1877 and 1883, which translated to a murder rate higher than any other city at that time, and only one person was ever convicted of a crime. The most prolific gunman of the day was John Wesley Hardin, who allegedly killed over twenty men in Texas in various gunfights, including one victim he killed in a hotel for snoring too loudly.

FIGURE The towns that sprouted up around gold strikes existed first and foremost as places for the men who struck it rich to spend their money. Stores, saloons, and brothels were among the first businesses to arrive. The combination of lawlessness, vice, and money often made for a dangerous mix.

Ranching brought with it its own dangers and violence. In the Texas cattle lands, owners of large ranches took advantage of their wealth and the new invention of barbed wire to claim the prime grazing lands and few significant watering holes for their herds. Those seeking only to move their few head of cattle to market grew increasingly frustrated at their inability to find even a blade of grass for their meager herds. Eventually, frustration turned to violence, as several ranchers resorted to vandalizing the barbed wire fences to gain access to grass and water for their steers. Such vandalism quickly led to cattle rustling, as these cowboys were not averse to leading a few of the rancher’s steers into their own herds as they left.

One example of the violence that bubbled up was the infamous Fence Cutting War in Clay County, Texas (1883–1884). There, cowboys began destroying fences that several ranchers erected along public lands: land they had no right to enclose. Confrontations between the cowboys and armed guards hired by the ranchers resulted in three deaths—hardly a “war,” but enough of a problem to get the governor’s attention. Eventually, a special session of the Texas legislature addressed the problem by passing laws to outlaw fence cutting, but also forced ranchers to remove fences illegally erected along public lands, as well as to place gates for passage where public areas adjoined private lands.

An even more violent confrontation occurred between large ranchers and small farmers in Johnson County, Wyoming, where cattle ranchers organized a “lynching bee” in 1891–1892 to make examples of cattle rustlers. Hiring twenty-two “invaders” from Texas to serve as hired guns, the ranch owners and their foremen hunted and subsequently killed the two rustlers best known for organizing the owners of the smaller Wyoming farms. Only the intervention of federal troops, who arrested and then later released the invaders, allowing them to return to Texas, prevented a greater massacre.

While there is much talk—both real and mythical—of the rough men who lived this life, relatively few women experienced it. While homesteaders were often families, gold speculators and cowboys tended to be single men in pursuit of fortune. The few women who went to these wild outposts were typically prostitutes, and even their numbers were limited. In 1860, in the Comstock Lode region of Nevada, for example, there were reportedly only thirty women total in a town of twenty-five hundred men. Some of the “painted ladies” who began as prostitutes eventually owned brothels and emerged as businesswomen in their own right; however, life for these young women remained a challenging one as western settlement progressed. A handful of women, numbering no more than six hundred, braved both the elements and male-dominated culture to become teachers in several of the more established cities in the West. Even fewer arrived to support husbands or operate stores in these mining towns.

As wealthy men brought their families west, the lawless landscape began to change slowly. Abilene, Kansas, is one example of a lawless town, replete with prostitutes, gambling, and other vices, transformed when middleclass women arrived in the 1880s with their cattle baron husbands. These women began to organize churches, school, civic clubs, and other community programs to promote family values. They fought to remove opportunities for prostitution and all the other vices that they felt threatened the values that they held dear. Protestant missionaries eventually joined the women in their efforts, and, while they were not widely successful, they did bring greater attention to the problems. As a response, the U.S. Congress passed both the Comstock Law (named after its chief proponent, anti-obscenity crusader Anthony Comstock) in 1873 to ban the spread of “lewd and lascivious literature” through the mail and the subsequent Page Act of 1875 to prohibit the transportation of women into the United States for employment as prostitutes. However, the “houses of ill repute” continued to operate and remained popular throughout the West despite the efforts of reformers.

The Assault on American Indian Life and Culture

LEARNING OBJECTIVES

As American settlers pushed westward, they inevitably came into conflict with Native tribes that had long been living on the land. Although the threat of attacks was quite slim and nowhere proportionate to the number of

U.S. Army actions directed against them, the occasional attack—often one of retaliation—was enough to fuel popular fear of Native peoples. The clashes, when they happened, were indeed brutal, although most of the brutality occurred at the hands of the settlers. Ultimately, the settlers, with the support of local militias and, later, with the federal government behind them, sought to eliminate the tribes from the lands they desired. This effort ultimately succeeded despite some Native military victories, and fundamentally changed the American Indian way of life.

CLAIMING LAND, RELOCATING LANDOWNERS

Back east, the popular vision of the West was of a vast and empty land. But of course this was an inaccurate depiction. On the eve of westward expansion, as many as 250,000 Native Americans, representing a variety of tribes, populated the Great Plains. Previous wars against tribes in the East in the early nineteenth century, as well as the failure of earlier treaties, led to a general policy of removal of these tribes west of the Mississippi. The Indian Removal Act of 1830 resulted in multiple forced removals, including the infamous “Trail of Tears,” which saw nearly fifty thousand Cherokee, Seminole, Choctaw, Chickasaw, and Creek people relocated to what is now Oklahoma between 1831 and 1838. Building upon such a history, the U.S. government was prepared, during the era of western settlement, to deal with tribes that settlers viewed as obstacles to expansion.

As settlers sought more land for farming, mining, and cattle ranching, the first strategy employed to deal with the perceived “Indian problem” was to negotiate treaties to move tribes out of the path of White settlers. In 1851, the chiefs of most of the Great Plains tribes agreed to the First Treaty of Fort Laramie. This agreement established distinct tribal borders, essentially codifying the reservation system. In return for annual payments of $50,000 to the tribes (originally guaranteed for fifty years, but later revised to last for only ten) as well as the hollow promise of noninterference from westward settlers, the participating tribes agreed to stay clear of the path of settlement. Due to government corruption, many annuity payments never reached the tribes, and some reservations were left destitute and near starving. In addition, within a decade, as the pace and number of western settlers increased, even designated reservations became prime locations for farms and mining. Rather than waiting for new treaties, settlers—oftentimes backed by local or state militia units—simply attacked the tribes out of fear or to force them from the land. Some American Indians resisted, only to then face massacres.

In 1862, frustrated and angered by the lack of annuity payments, increasing hunger among their people, and the continuous encroachment on their reservation lands, Dakotas in Minnesota rebelled in what became known as the Dakota War or the War of 1862, killing the White settlers who moved onto their tribal lands. Over one thousand White settlers were captured or killed in the attack, before an armed militia regained control. Of the four hundred Sioux captured by U.S. troops, 303 were sentenced to death, but President Lincoln intervened, releasing all but thirty-eight of the men. Lincoln’s government hanged the remaining thirty-eight Dakota men in the largest mass execution in the country’s history. The government imprisoned other Dakota participants in the uprising, and banished their families from Minnesota. Settlers in other regions responded to news of this raid with fear and aggression. In Colorado, Arapahoe and Cheyenne tribes fought back against land encroachment; White militias then formed, decimating even some of the tribes that were willing to cooperate. One of the more vicious examples was near Sand Creek, Colorado, where Colonel John Chivington led a militia raid upon a camp in which the Cheyenne leader Black Kettle had already negotiated a peaceful settlement. The camp was flying both the American flag and the white flag of surrender when Chivington’s troops murdered close to one hundred people, the majority of them women and children, and mutilated the bodies in what became known as the Sand Creek Massacre. For the rest of his life, Chivington would proudly display his collection of nearly one hundred Native American scalps from that day. Subsequent investigations by the U.S. Army condemned Chivington’s tactics and their results; however, the raid served as a model for some settlers who sought any means by which to eradicate the perceived Indian threat. The incident highlighted growing disagreement between Americans in the eastern and western parts of the nation about how best to handle Indian affairs.

Hoping to forestall similar uprisings and all-out wars, the U.S. Congress commissioned a committee to investigate the causes of such incidents. The subsequent report of their findings led to the passage of two additional treaties: the Second Treaty of Fort Laramie and the Treaty of Medicine Lodge Creek, both designed to move the remaining tribes to even more remote reservations. The Second Treaty of Fort Laramie moved the remaining Lakota people to the Black Hills in the Dakota Territory and the Treaty of Medicine Lodge Creek moved the Cheyenne, Arapaho, Kiowa, and Comanche people to Indian Territory, later to become the State of Oklahoma.

The agreements were short-lived, however. With the subsequent discovery of gold in the Black Hills, settlers seeking their fortune began to move upon the newly granted Sioux lands with support from U.S. cavalry troops. By the middle of 1875, thousands of White prospectors were illegally digging and panning in the area. The Lakota people protested the invasion of their territory and the violation of sacred ground. The government offered to lease the Black Hills or to pay $6 million if the Indians were willing to sell the land. When the tribes refused, the government imposed what it considered a fair price for the land, ordered the Indians to move, and in the spring of 1876, made ready to force them onto the reservation.

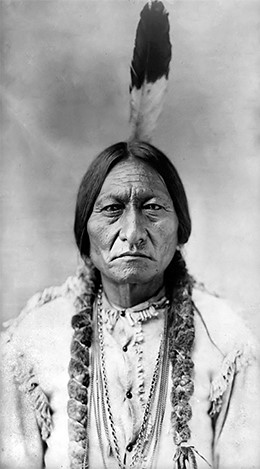

In the Battle of Little Bighorn, perhaps the most famous battle of the American West, a Hunkpapa Lakota chief,

Sitting Bull, urged Native Americans from all neighboring tribes to join his men in defense of their lands (Figure 17.13). At the Little Bighorn River, the U.S. Army’s Seventh Cavalry, led by Colonel George Custer, sought a showdown. Driven by his own personal ambition, on June 25, 1876, Custer foolishly attacked what he thought was a minor encampment. Instead, it turned out to be a large group of Lakotas, Cheyennes, and Arapahos. The warriors—nearly three thousand in strength—surrounded and killed Custer and 262 of his men and support units, in the single greatest loss of U.S. troops to a Native American force in the era of westward expansion.

FIGURE The iconic Sitting Bull led Lakota, Cheyenne, and Arapaho warriors in what was the largest victory against American troops during Westward expansion. While the Battle of the Little Big Horn was a rout by the Lakotas and their allies over Custer’s troops, Native American resistance in the American West ultimately failed to halt American expansion.

AMERICAN INDIAN SUBMISSION

Despite their success at Little Bighorn, neither the Lakota people nor any other Plains tribes followed this battle with any other armed encounter. Rather, they either returned to tribal life or fled out of fear of remaining troops, until the U.S. Army arrived in greater numbers and began to exterminate Indian encampments and force others to accept payment for forcible removal from their lands. Sitting Bull himself fled to Canada, although he later returned in 1881 and subsequently worked in Buffalo Bill’s Wild West show. In Montana, the Blackfoot and Crow were forced to leave their tribal lands. In Colorado, the Utes gave up their lands after a brief period of resistance. In Idaho, most of the Nez Perce gave up their lands peacefully, although in an incredible episode, a band of some eight hundred Indians sought to evade U.S. troops and escape into Canada.

|

MY STORY |

|

I Will Fight No More: Chief Joseph’s Capitulation Chief Joseph, known to his people as “Thunder Traveling to the Loftier Mountain Heights,” was the chief of the Nez Perce tribe, and he had realized that they could not win against the White people. In order to avoid a war that would undoubtedly lead to the extermination of his people, he hoped to lead his tribe to Canada, where they could live freely. He led a full retreat of his people over fifteen hundred miles of mountains and harsh terrain, only to be caught within fifty miles of the Canadian border in late 1877. His speech has remained a poignant and vivid reminder of what the tribe had lost. “Tell General Howard I know his heart. What he told me before, I have it in my heart. I am tired of fighting. Our Chiefs are killed; Looking Glass is dead, Ta Hool Hool Shute is dead. The old men are all dead. It is the young men who say yes or no. He who led on the young men is dead. It is cold, and we have no blankets; the little children are freezing to death. My people, some of them, have run away to the hills, and have no blankets, no food. No one knows where they are—perhaps freezing to death. I want to have time to look for my children, and see how many of them I can find. Maybe I shall find them among the dead. Hear me, my Chiefs! I am tired; my heart is sick and sad. From where the sun now stands I will fight no more forever.” “—Chief Joseph, 1877” |

The final episode in the so-called Indian Wars occurred in 1890, at the Wounded Knee Massacre in South Dakota. On their reservation, the Lakota people had begun to perform the “Ghost Dance,” which told of a Messiah who would deliver the tribe from its hardship, with such frequency that White settlers began to worry that another uprising would occur. The 7th Calvary prepared to round up the people performing the Ghost Dance. Frightened after the death of Sitting Bull at the hands of tribal police, a group of Lakota Ghost Dancers led by Bigfoot fled. When the 7th Cavalry caught up to them at Wounded Knee, South Dakota on December 29, 1890, the Lakotas prepared to surrender. Although the accounts are unclear, an apparent accidental rifle discharge by a young Lakota man preparing to lay down his weapon led the U.S. soldiers to begin firing indiscriminately upon the Native Americans. What little resistance the Lakotas mounted with a handful of concealed rifles at the outset of the fight diminished quickly, with the troops eventually massacring between 150 and 300 men, women, and children. The U.S. troops suffered twenty-five fatalities, some of which were the result of their own crossfire. Captain Edward Godfrey of the Seventh Cavalry later commented, “I know the men did not aim deliberately and they were greatly excited. I don’t believe they saw their sights. They fired rapidly but it seemed to me only a few seconds till there was not a living thing before us; warriors, squaws, children, ponies, and dogs . . . went down before that unaimed fire.” The United States awarded twenty of these soldiers the Congressional Medal of Honor, the nation’s highest military honor. With this last show of brutality, the Indian Wars came to a close. U.S. government officials had already begun the process of seeking an alternative to the meaningless treaties and costly battles. A more effective means with which to address the public perception of the “Indian problem” was needed. Americanization provided the answer.

AMERICANIZATION

Through the years of the Indian Wars of the 1870s and early 1880s, opinion back east was mixed. There were many who felt, as General Philip Sheridan (appointed in 1867 to pacify the Plains Indians) allegedly said, that “the only good Indian was a dead Indian.” But increasingly, several American reformers who would later form the backbone of the Progressive Era had begun to criticize the violence, arguing that the government should help the Native Americans through an Americanization policy aimed at assimilating them into American society. Individual land ownership, Christian worship, and education for children became the cornerstones of this new assault on Native life and culture.

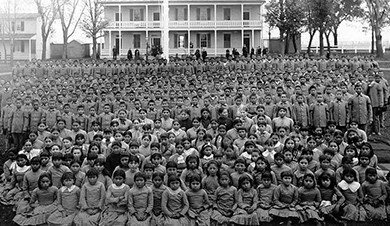

Beginning in the 1880s, clergymen, government officials, and social workers all worked to assimilate Native peoples into American life. The government helped reformers remove Native American children from their homes and the cultural influence of their families and place them in boarding schools, such as the Carlisle Indian School, where they were forced to abandon their tribal traditions and embrace Euro-American social and cultural practices. Such schools acculturated Native American boys and girls and provided vocational training for males and domestic science classes for females. Boarding schools sought to convince Native children to abandon their language, clothing, and social customs for a more Euro-American lifestyle (Figure 17.14).

FIGURE 17.14 The federal government’s policy towards Native Americans shifted in the late 1880s from the reservation system to assimilating them into the American ideal.

A vital part of the assimilation effort was land reform. During earlier negotiations, the government had recognized Native American communal ownership of land. Although many tribes recognized individual families’ use rights to specific plots of land, the tribe owned the land. As a part of their plan to Americanize the tribes, reformers sought legislation to replace this concept with the popular Euro-American notion of real estate ownership and self-reliance. One such law was the Dawes Severalty Act of 1887, named after a reformer and senator from Massachusetts. In what was essentially a new version of the original Homestead Act, the Dawes Act permitted the federal government to divide the lands of any tribe and grant 160 acres of farmland or 320 acres of grazing land to each head of family, with lesser amounts to single persons and others. In a nod towards the paternal relationship with which White people viewed Native Americans—similar to the justification of the previous treatment of enslaved African Americans—the Dawes Act permitted the federal government to hold an individual Native American’s newly acquired land in trust for twenty-five years. Only then would they obtain full title and be granted the citizenship rights that land ownership entailed. It would not be until 1924 that formal citizenship was granted to all Native Americans. Under the Dawes Act, Native Americans were assigned the most arid, useless land and “surplus” land went to White settlers. The government sold as much as eighty million acres of Native American land to White American settlers.

As White Americans pushed west, they not only collided with Native American tribes but also with Hispanic Americans and Chinese immigrants. Hispanics in the Southwest had the opportunity to become American citizens at the end of the Mexican-American war, but their status was markedly second-class. Chinese immigrants arrived en masse during the California Gold Rush and numbered in the hundreds of thousands by the late 1800s, with the majority living in California, working menial jobs. These distinct cultural and ethnic groups strove to maintain their rights and way of life in the face of persistent racism and entitlement. But the large number of White settlers and government-sanctioned land acquisitions left them at a profound disadvantage. Ultimately, both groups withdrew into homogenous communities in which their language and culture could survive.

CHINESE IMMIGRANTS IN THE AMERICAN WEST

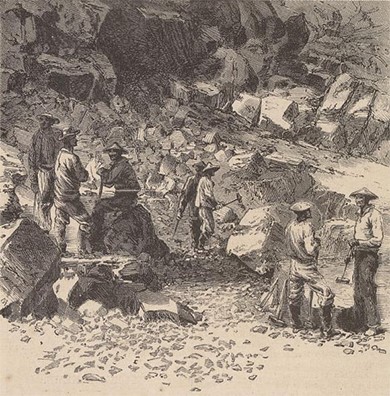

The initial arrival of Chinese immigrants to the United States began as a slow trickle in the 1820s, with barely 650 living in the U.S. by the end of 1849. However, as gold rush fever swept the country, Chinese immigrants, too, were attracted to the notion of quick fortunes. By 1852, over 25,000 Chinese immigrants had arrived, and by 1880, over 300,000 Chinese lived in the United States, most in California. While they had dreams of finding gold, many instead found employment building the first transcontinental railroad (Figure 17.15). Some even traveled as far east as the former cotton plantations of the Old South, which they helped to farm after the Civil War. Several thousand of these immigrants booked their passage to the United States using a “credit-ticket,” in which their passage was paid in advance by American businessmen to whom the immigrants were then indebted for a period of work. Most arrivals were men: Few wives or children ever traveled to the United States. As late as 1890, less than 5 percent of the Chinese population in the U.S. was female. Regardless of gender, few Chinese immigrants intended to stay permanently in the United States, although many were reluctantly forced to do so, as they lacked the financial resources to return home.

FIGURE Building the railroads was dangerous and backbreaking work. On the western railroad line, Chinese migrants, along with other non-White workers, were often given the most difficult and dangerous jobs of all. Prohibited by law since 1790 from obtaining U.S. citizenship through naturalization, Chinese immigrants faced harsh discrimination and violence from American settlers in the West. Despite hardships like the special tax that Chinese miners had to pay to take part in the Gold Rush, or their subsequent forced relocation into Chinese districts, these immigrants continued to arrive in the United States seeking a better life for the families they left behind. Only when the Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882 forbade further immigration from China for a ten-year period did the flow stop.

The Chinese community banded together in an effort to create social and cultural centers in cities such as San Francisco. In a haphazard fashion, they sought to provide services ranging from social aid to education, places of worship, health facilities, and more to their fellow Chinese immigrants. As Chinese workers began competing with White Americans for jobs in California cities, the latter began a system of built-in discrimination. In the 1870s, White Americans formed “anti-coolie clubs” (“coolie” being a racial slur directed towards people of any Asian descent), through which they organized boycotts of Chinese-produced products and lobbied for anti-Chinese laws. Some protests turned violent, as in 1885 in Rock Springs, Wyoming, where tensions between White and Chinese immigrant miners erupted in a riot, resulting in over two dozen Chinese immigrants being murdered and many more injured.

Slowly, racism and discrimination became law. The new California constitution of 1879 denied naturalized

Chinese citizens the right to vote or hold state employment. Additionally, in 1882, the U.S. Congress passed the Chinese Exclusion Act, which forbade further Chinese immigration into the United States for ten years. The ban was later extended on multiple occasions until its repeal in 1943. Eventually, some Chinese immigrants returned to China. Those who remained were stuck in the lowest-paying, most menial jobs. Several found assistance through the creation of benevolent associations designed to both support Chinese communities and defend them against political and legal discrimination; however, the history of Chinese immigrants to the United States remained largely one of deprivation and hardship well into the twentieth century.

|

DEFINING AMERICAN |

|

The Backs that Built the Railroad Below is a description of the construction of the railroad in 1867. Note the way it describes the scene, the laborers, and the effort. “The cars now (1867) run nearly to the summit of the Sierras. . . . four thousand laborers were at work—onetenth Irish, the rest Chinese. They were a great army laying siege to Nature in her strongest citadel. The rugged mountains looked like stupendous ant-hills. They swarmed with Celestials, shoveling, wheeling, carting, drilling and blasting rocks and earth, while their dull, moony eyes stared out from under immense basket-hats, like umbrellas. At several dining camps we saw hundreds sitting on the ground, eating soft boiled rice with chopsticks as fast as terrestrials could with soup-ladles. Irish laborers received thirty dollars per month (gold) and board; Chinese, thirty-one dollars, boarding themselves. After a little experience the latter were quite as efficient and far less troublesome.” “—Albert D. Richardson, Beyond the Mississippi” Several great American advancements of the nineteenth century were built with the hands of many other nations. It is interesting to ponder how much these immigrant communities felt they were building their own fortunes and futures, versus the fortunes of others. Is it likely that the Chinese laborers, many of whom died due to the harsh conditions, considered themselves part of “a great army”? Certainly, this account reveals the unwitting racism of the day, where workers were grouped together by their ethnicity, and each ethnic group was labeled monolithically as “good workers” or “troublesome,” with no regard for individual differences among the hundreds of Chinese or Irish workers. |

HISPANIC AMERICANS IN THE AMERICAN WEST

The Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo, which ended the Mexican-American War in 1848, promised U.S. citizenship to the nearly seventy-five thousand Hispanics now living in the American Southwest; approximately 90 percent accepted the offer and chose to stay in the United States despite their immediate relegation to second class citizenship status. Relative to the rest of Mexico, these lands were sparsely populated and had been so ever since the country achieved its freedom from Spain in 1821. In fact, New Mexico—not Texas or California—was the center of settlement in the region in the years immediately preceding the war with the United States, containing nearly fifty thousand Mexicans. However, those who did settle the area were proud of their heritage and ability to develop rancheros of great size and success. Despite promises made in the treaty, these Californios—as they came to be known—quickly lost their land to White settlers who simply displaced the rightful landowners, by force if necessary. Repeated efforts at legal redress mostly fell upon deaf ears. In some instances, judges and lawyers would permit the legal cases to proceed through an expensive legal process only to the point where Hispanic landowners who insisted on holding their ground were rendered penniless for their efforts.

Much like Chinese immigrants, Hispanic citizens were relegated to the worst-paying jobs under the most terrible working conditions. They worked as peóns(manual laborers similar to enslaved people), vaqueros (cattle herders), and cart men (transporting food and supplies) on the cattle ranches that White landowners possessed, or undertook the most hazardous mining tasks (Figure 17.16).

FIGURE Mexican ranchers had worked the land in the American Southwest long before American “cowboys” arrived. In what ways might the Mexican vaquero pictured above have influenced the American cowboy?

In a few instances, frustrated Hispanic citizens fought back against the White settlers who dispossessed them of their belongings. In 1889–1890 in New Mexico, several hundred Mexican Americans formed las Gorras Blancas(the White Caps) to try and reclaim their land and intimidate White Americans, preventing further land seizures. White Caps conducted raids of White farms, burning homes, barns, and crops to express their growing anger and frustration. However, their actions never resulted in any fundamental changes. Several White Caps were captured, beaten, and imprisoned, whereas others eventually gave up, fearing harsh reprisals against their families. Some White Caps adopted a more political strategy, gaining election to local offices throughout New Mexico in the early 1890s, but growing concerns over the potential impact upon the territory’s quest for statehood led several citizens to heighten their repression of the movement. Other laws passed in the United States intended to deprive Mexican Americans of their heritage as much as their lands. “Sunday Laws” prohibited “noisy amusements” such as bullfights, cockfights, and other cultural gatherings common to Hispanic communities at the time. “Greaser Laws” permitted the imprisonment of any unemployed Mexican American on charges of vagrancy. Although Hispanic Americans held tightly to their cultural heritage as their remaining form of self-identity, such laws did take a toll.

In California and throughout the Southwest, the massive influx of Anglo-American settlers simply overran the Hispanic populations that had been living and thriving there, sometimes for generations. Despite being U.S. citizens with full rights, Hispanics quickly found themselves outnumbered, outvoted, and, ultimately, outcast. Corrupt state and local governments favored White people in land disputes, and mining companies and cattle barons discriminated against them, as with the Chinese workers, in terms of pay and working conditions. In growing urban areas such as Los Angeles, barrios, or clusters of working-class homes, grew more isolated from the White American centers. Hispanic Americans, like the Native Americans and Chinese, suffered the fallout of the White settlers’ relentless push west.

Citation & Source Note:

Corbett, P. Scott, Volker Janssen, John M Lund, Todd Pfannestiel, Sylvie Waskiewicz, and Paul Vickery. “Go West Young Man! Westward Expansion, 1840-1900.” In U.S. History. Houston, TX: OpenStax, 2014. https://openstax.org/books/us-history/pages/17-introduction.