About Annotation

Introduction*

Annotation, the act of adding additional information as a note attached to a specific part of a published work (or simply highlighting key passages), is a familiar academic but also everyday practice.

As described in Remi Kalir and Antero Garcia’s book, Annotation

Annotation provides information, making knowledge more accessible. Annotation shares commentary, making both expert opinion and everyday perspective more transparent. Annotation sparks conversation, making our dialogue – about art, religion, culture, politics, and research – more interactive. Annotation expresses power, making civic life more robust and participatory. And annotation aids learning, augmenting our intellect, cognition, and collaboration. This is why annotation matters.

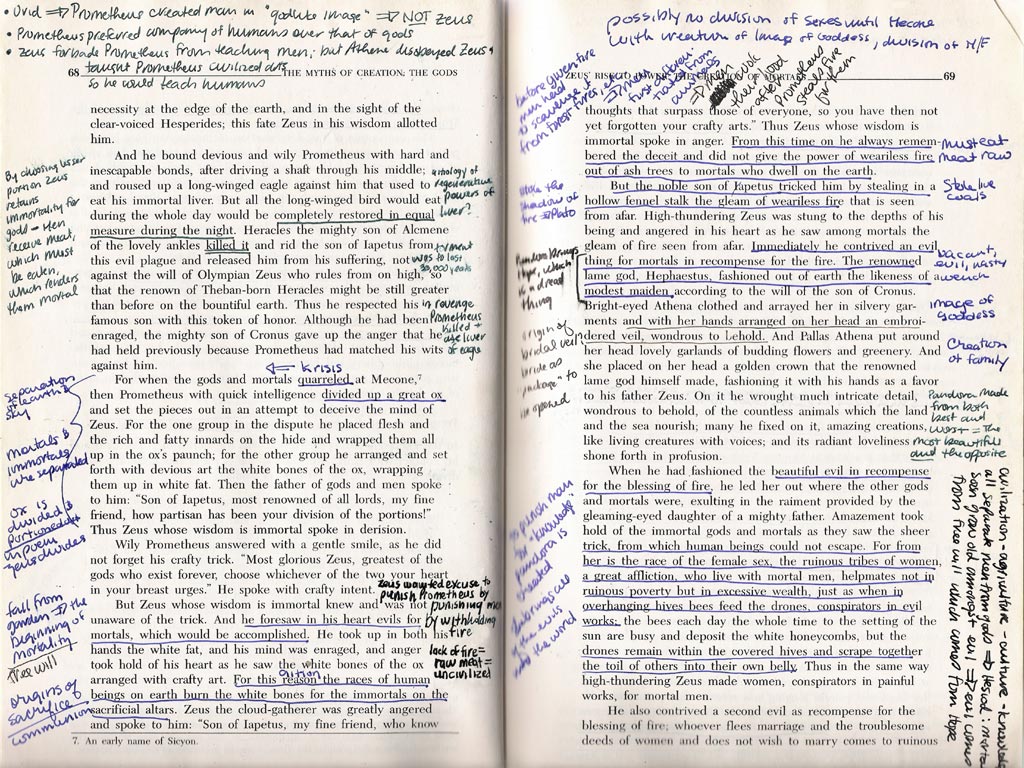

Making notes in printed works is a centuries-old practice, the authors share some historical examples.

Marginalia thrived in England during the sixteenth century, as studies of book culture during the rule of Elizabeth I and James I demonstrate.Annotated books were routinely exchanged among scholars and friends as “social activity” throughout the Victorian era. Some of the most significant commentary about the Talmud, first written in the eleventh century, has been featured prominently as annotation in print editions since the early 1500s. Today, scientists’ annotation of the human genome and proteome for large-scale biomedical research relies upon techniques that are both similar to and also very different from linguists and historians who have translated, annotated, and digitally archived Babylonian and Assyrian clay tablets. From the annotatio of Roman imperial law to the medieval gloss, annotation nowadays helps people to write computer code, evaluate chess games, and interpret rap lyrics.

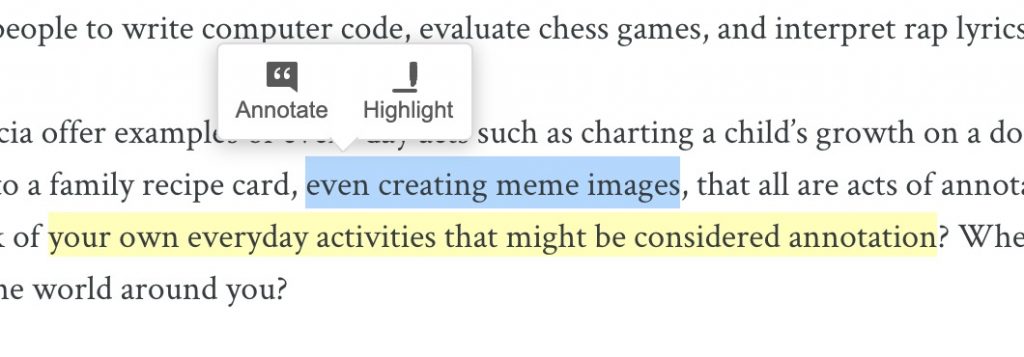

Kalir and Garcia offer examples of everyday acts such as charting a child’s growth on a doorway, adding notes to a family recipe card, and even creating meme images, which all are acts of annotation. Can you think of your everyday activities that might be considered annotation? Where do you see it in the world around you?

Web annotation not only provides similar functionality but expands its capabilities by having it take place in an open, common space making it a social process. With the open source platform Hypothesis, we all can add commentary, questions, and additional resources to any public content on the web. Including this textbook.

If this is new to you, we can start right here with some practice annotation.

ANNOTATE NOW WITH HYPOTHESIS!*

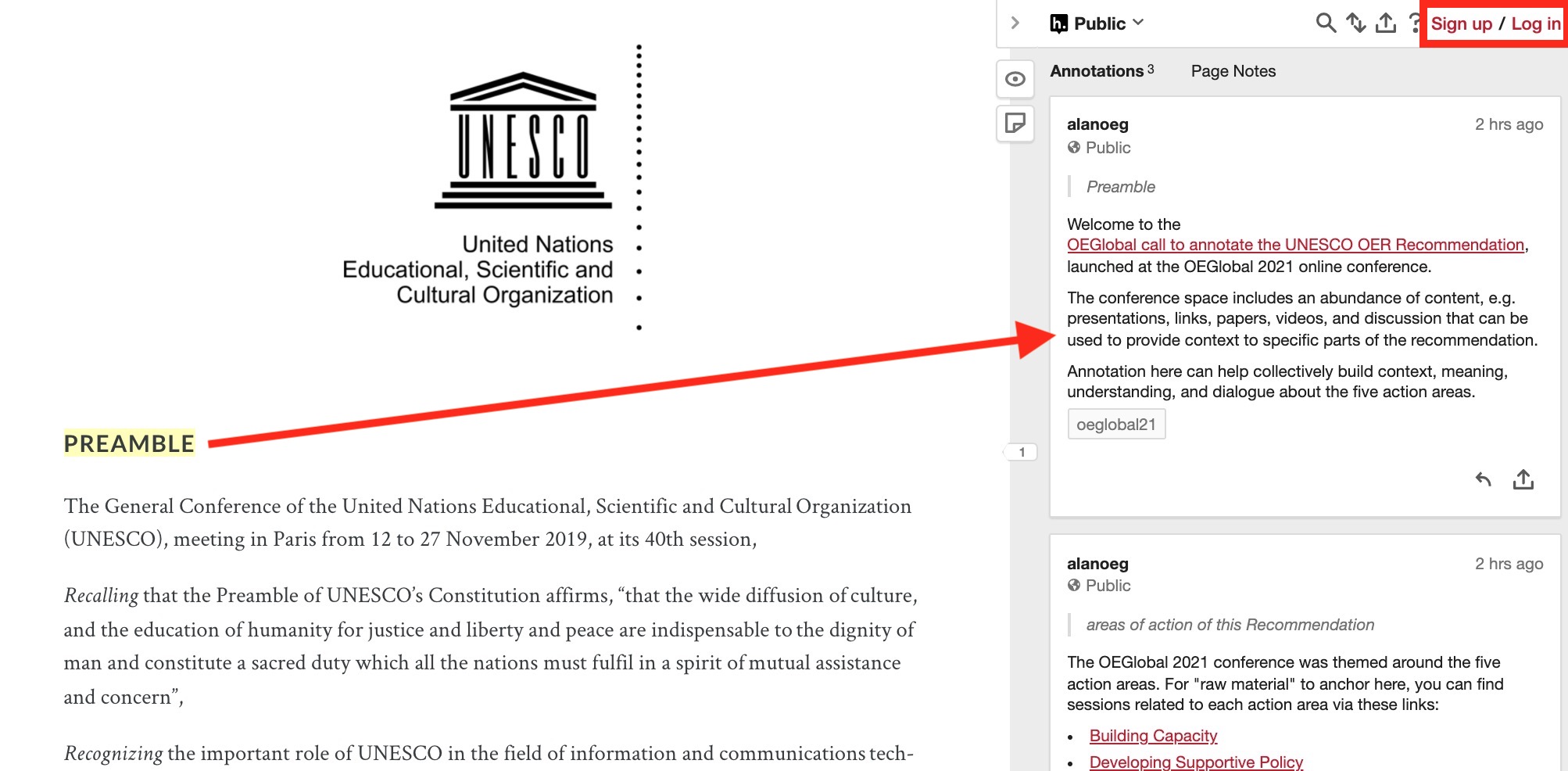

Hypothes.is is a free, open-source social annotation technology regularly used by educators. It adds an annotation layer to any public web page or document. To participate in social annotation conversations, start by creating a free Hypothesis account.

The entire sign-up process will take less than one minute. In fact, you will be able to log in or create an account directly from within this Pressbook.

Please note that Hypothesis is not a social network and does not collect any personally identified information except for an email address. Additionally, all public annotations, by default, are licensed Creative Commons CC0.

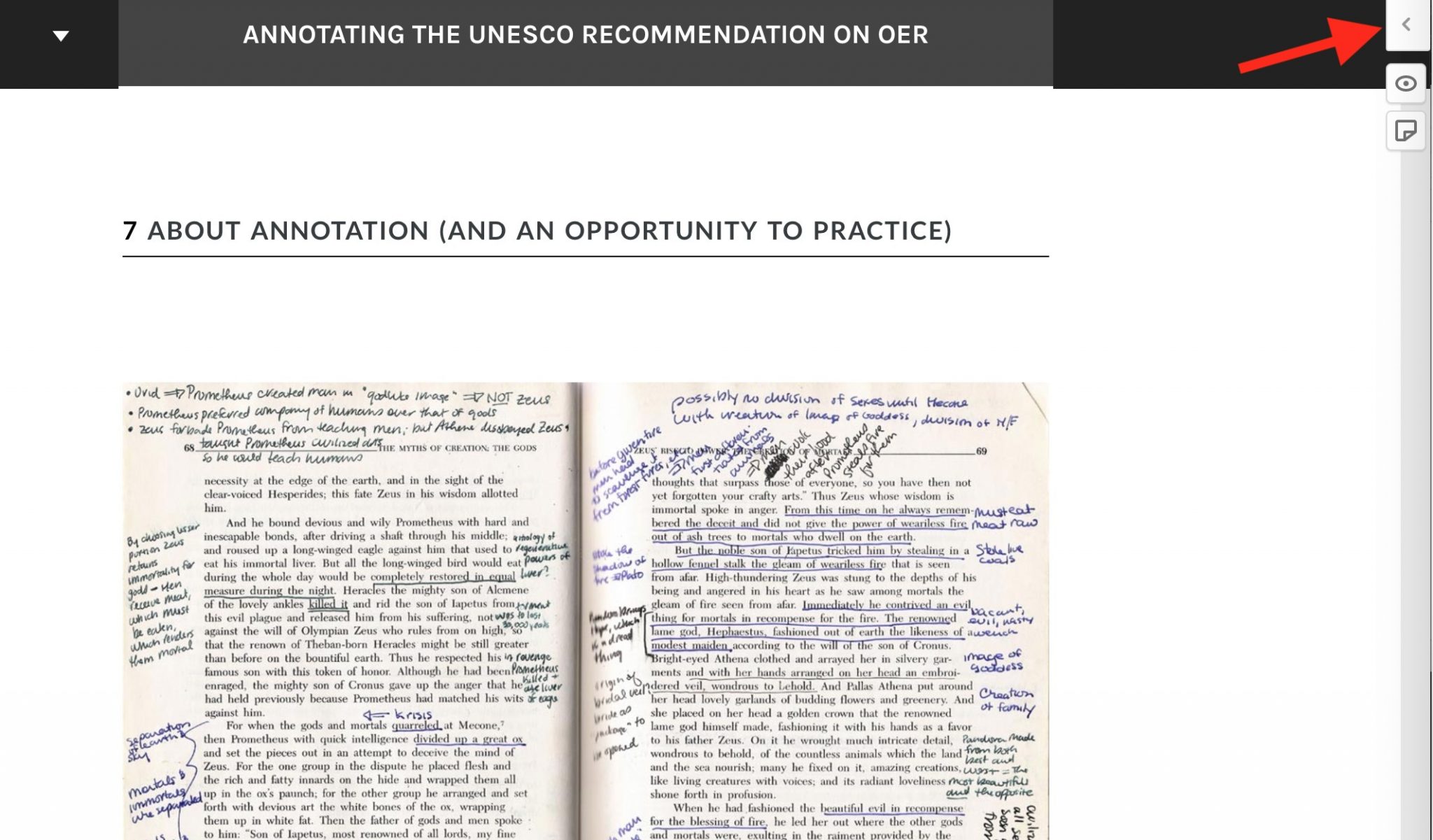

The pages of this book are already set up to be annotated with Hypothesis. How do you know? Look in the upper right corner a gray button with a < symbol.

Upon opening the Hypothesis tools via the < button, you see the notes previously added. If you are not logged in to Hypothesis, you can do it here or create a new account. Once logged in, you can even reply to an existing annotation.

A yellow highlight color will indicate all annotations available on this page. Click any annotation to read it in the Hypothesis sidebar.

How do we create a new note? Let’s annotate this page, maybe in the area that mentions everyday acts of annotation or where we see it in the real world. How does one annotate? Just select a phrase or word that you would like to add information to (shorter selections of text work better). Hypothesis offers right there a choice to add a note as an annotation.

Choosing Annotate opens a small composition window in the Hypothesis sidebar. You can add text, create hyperlinks, and insert images or media. You will have the option to “Post to Public” for anyone who has access to the textbook to see. Another option is “Post to Private,” which provides highlights and notes for your viewing, or you may join a specific group where you can collaboratively annotate a document with select peers.

Use this page as a place to practice writing annotations. Once you understand the process, continue to the next chapter, where you may begin annotating the text.

Expectations for Annotation

In the EDUC 4353 Secondary Teaching Methods & Practices course that this textbook was originally designed, there is an expectation that students will participate in actively annotating throughout the semester. The work of Professor Brian Watkins inspires the expectations outlined below to encourage students to engage with each other’s thoughts, questions, opinions, and experiences while interacting with the content. Your instructor will send you an invite to join the private EDUC 4353 group specifically set up for collaborative annotation during the course.

The basic requirement is that you take three actions per reading assignment. Any annotation is an action, with some caveats.

An action is:

-

- Many things: a question, a comment, an answer, some context you looked up and wanted to add – each of these is an annotation and, therefore, an action in the basic sense.

- Constructive – It’s made in good faith to build up and add value to the people reading the text. It can be a question, answer, or informative comment. Good questions cannot be answered in a few words and might help someone else with a similar question or another student looking to comment. Good answers are thoughtful. Good arguments are productive, allowing for the possibility of misunderstanding on all sides and creating spaces for further understanding.

- Considerate – At no point will a student be the target of a dismissive or otherwise negative comment. Doing so will result in a student receiving an unsatisfactory score for participation in that reading assignment.

- Substantive – It is more than a very short reply. “I agree” or “Why?” will not count toward your three actions, though you can post any number of smaller annotations as you would like. They just won’t count for your “three actions.”

References & Attribution

Attribution: “Introduction” and “Annotate with Hypothesis” sections were adapted in part from Annotating the UNESCO Recommendation on OER by UNESCO, licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 4.0 International License