17 Find the Good Argument

Learning Objectives

- Distinguish between academic arguments and popular arguments

- Explain deductive and inductive reasoning

- Apply models of argumentation to original arguments

Download and/or print this chapter: Reading, Thinking, and Writing for College Classes – Ch. 17 Find the Good Argument

Argument as Dance

The word argument often means something negative. In Nina Paley’s cartoon (see figure 9.1), the argument is literally a catfight. Rather than envisioning argument as something productive and useful, we imagine intractable sides and use descriptors such as “bad,” “heated,” and “violent.” We rarely say, “Great argument. Thanks!” Even when we write an academic “argument paper,” we imagine our own ideas battling others.

Linguists George Lakoff and Mark Johnson explain that the controlling metaphor we use for argument in Western culture is war:

It is important to see that we don’t just talk about arguments in terms of war. We actually win or lose arguments. We see the person we are arguing with as an opponent. We attack his positions and we defend our own. We gain and lose ground. We plan and use strategies. If we find a position indefensible, we can abandon it and take a new line of attack. Many of the things we do in arguing are partially structured by the concept of war. (4)

The war metaphor offers many limiting assumptions: there are only two sides, someone must win decisively, and compromise means losing. The metaphor also creates a false opposition where argument (war) is action and its opposite is peace or inaction. Finding better arguments is not about finding peace—the opposite of antagonism. Quite frankly, getting mad can be productive. Ardent peace advocates, such as Jane Addams, Mahatma Gandhi, and Martin Luther King Jr., offer some of the most compelling arguments of our time through concepts that are hardly inactive, like civil disobedience.

While “argument is war” may be the default mode for Americans, it is not the only way to argue. Lakoff and Johnson ask their readers to imagine something like “argument is dance” rather than “argument is war” (5). While we can imagine many alternatives to the war metaphor, concepts like argument as collaboration are more common in an academic setting, even if they are not commonly used in our everyday lives. In an academic argument, the goal is to show other educated readers why a conclusion is sound and worth considering. Academic arguments attempt to move us toward a better understanding of the world, to improve the ways we do things, to make our lives better.

In presenting an academic argument, then, you are not simply arguing your opinion. You are showing readers that you have good reasons for the opinions you hold. Your goal is not necessarily to get readers to change their positions or to accept wholeheartedly your opinion; instead, you may want to help readers understand a perspective or point of view, to increase their understanding of an issue, or to get them to shift their thinking on an issue–all legitimate reasons to write an argument. Whatever your goal, you’re attempting to engage with readers not attack anyone or “prove” your point beyond a shadow of a doubt. When writing a good academic argument, you’re imagining what readers think and helping them see how you think. Argument as a conversation or as a dance is a more accurate metaphor for academic arguments.

Argument in the Media

Of course, argument as conversation is not the prevailing metaphor for public argumentation we see/hear in the mainstream media. One can hardly fault the average American for not being able to imagine argument beyond the war metaphor. Think back to the coverage of major elections in recent years. Both sides (Democrat/Republican) dig in their heels and defend every position, lambasting the opposition and stirring up voters’ emotions. Our political landscape is divided into two sides with no alternatives, and we learn from websites such as FactCheck.org that politicians from all parties present inaccurate information and employ fallacies rather than good reasoning. The so-called “debates” politicians engage in are more like speeches given to a camera than actual arguments. News outlets, social media, and other venues exacerbate the problem.

Unfortunately, these shallow public models can influence argumentation in the classroom. One of the ways we learn about argument is to think in terms of pro and con arguments. This replicates the liberal/conservative dynamic we often see in the papers or on television, as if there are only two sides to health care, the economy, war, the deficit. You are either for or against gun control, for or against abortion, for or against the environment, for or against everything. Put this way, the absurdity is more obvious. For example, we assume that someone who claims to be an “environmentalist” agrees with every part of the green movement. However, it is quite possible to develop an environmentally sensitive argument that argues against a particular recycling program.

While many pro and con arguments are valid, they can erase nuance and shut down the very purpose of having an argument: the possibility that you might change your mind, learn something new, or solve a problem. When all angles are not explored or when bad reasoning is used, we are left with ethically suspect public discussions that cannot possibly get at the roots of an issue or work toward solutions. Controversial issues are complicated, and the either/or fallacy of public argument has no place in an academic argument.

Rather than an either/or proposition, in an academic setting, argument is complex. An academic argument can be logical, rational, emotional, fruitful, useful, and even enjoyable. As a matter of fact, the idea that argument is necessary (and therefore not always about war or even about winning) is an important notion in a culture that values democracy and equity. In America, where nearly everyone you encounter has a different background and/or political or social view, skill in arguing seems to be paramount, whether you are inventing an argument or recognizing a good one when you see it.

The remainder of this chapter presents three models of argumentation that go beyond pro and con. Each model can help you pay more attention to the details of an argument and can offer strategies for developing sound, ethically aware arguments.

Inductive and Deductive Reasoning

A key feature in all good arguments is the use of good inductive and deductive reasoning. These two terms describe the two ways we come to conclusions: we either build upon examples and generalize (inductive) or we draw connections between what we already know and/or discover (deductive). Knowing the differences between these two types of reasoning is not crucial to writing a good argument, but if you understand how reasoning works, you’re likely to examine your own reasoning more carefully.

When we discuss logical appeals or logos, we’re discussing how well an argument employs inductive and deductive reasoning. If our readers question our conclusions, it’s likely because we have not carefully considered the way we reached those conclusions. We might even have logical fallacies if evidence is presented illogically. In an academic setting, logic is key to making good arguments. Logic is not synonymous with fact or truth–you can be logical without being truthful–but logical appeals are necessary to go beyond the simplistic pro/con arguments that we see so often in the media. Moreover, a strong argument based on logic demonstrates your ability to think critically, and thinking critically means thinking deductively and inductively.

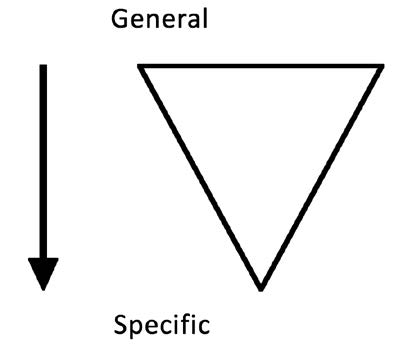

Deductive reasoning (see figure 9.3) starts from a premise that is a generalization about a large class of ideas, people, and so on and moves to a specific conclusion about a smaller category of ideas or things (e.g., “All cats hate water; therefore, my neighbor’s cat will not jump in our pool”). While the first premise is the most general, the second premise is a more particular observation. So the argument is created through common beliefs/observations that are compared to create an argument. For example,

Major Premise: People who burn flags are unpatriotic.

Minor Premise: Sara burned a flag.

Conclusion: Sara is unpatriotic.

The above is called a syllogism. As we can see in the example, the major premise offers a general belief held by some groups and the minor premise is a particular observation. The conclusion is drawn by comparing or adding up the premises and developing a conclusion. If you work hard enough, you can often take a complex argument and boil it down to several syllogisms or arguments within an argument. This can reveal a great deal about the argument that is not apparent in the longer, more complex version.

For example, Stanley Fish, professor and New York Times columnist, offers a syllogism in his July 22, 2007, blog entry titled “Democracy and Education”: “The syllogism underlying the argument is (1) America is a democracy (2) Schools and universities are situated within that democracy (3) Therefore schools and universities should be ordered and administered according to democratic principles.”

Fish offered the syllogism as a way to summarize the responses to his argument that students do not, in fact, have the right to free speech in a university classroom. The responses to Fish’s standpoint were vehemently opposed to his understanding of free speech rights and democracy. In short, they didn’t agree with his deductive reasoning. To those readers, the proposal to order schools and universities as a democracy–his thesis or main argument–was not a logical conclusion to the two premises. Yes, America is a democracy (premise 1), and yes, schools are universities are situated within that democracy (premise 2), but so are grocery stores and art museums and many other organizations or companies. Simply being situated within a democracy does not necessarily mean the principles of democracy are required. Readers, therefore, might question his deductive reasoning.

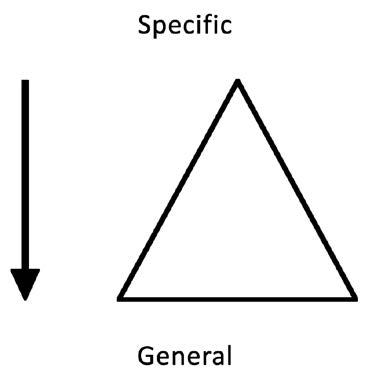

Inductive reasoning moves in a different direction than deductive reasoning (see figure 9.4). Inductive reasoning starts with a particular or local statement and moves to a more general conclusion. Think of inductive reasoning as a stacking of evidence. The more particular examples you give, the more it seems that your conclusion is correct.

Inductive reasoning is a common method for arguing, especially when the conclusion is an obvious probability. Inductive reasoning is the most common way that we move around in the world. If we experience something habitually, we reason that it will happen again. For example, if we walk down a city street and every person smiles, we might reason that this is a “nice town.” This seems logical. We have taken many similar, particular experiences (smiles) and used them to make a general conclusion (the people in the town are nice).

Most of the time, this reasoning works. However, we know that it can also lead us in the wrong direction. Perhaps the people were smiling because we were wearing inappropriate clothing (country togs in a metropolitan city), or perhaps only the people living on that particular street are “nice” and the rest of the town is unfriendly. Research papers sometimes rely too heavily on this logical method. Writers assume that finding ten versions of the same argument somehow proves that the point is true.

Here is another example: In Ann Coulter’s book Guilty: Liberal “Victims” and Their Assault on America, she makes her (in)famous argument that single motherhood is the cause of many of America’s ills. She creates this argument through a piling of evidence. She lists statistics by sociologists; she lists all the single moms who killed their children; she lists stories of single mothers who say outrageous things about their lives, children, or marriages in general; and she ends with a list of celebrity single moms that most would agree are not good examples of motherhood. This list leads her to conclude, “Look at almost any societal problem and you will find it is really a problem of single mothers” (36). But some readers might question her conclusion by arguing that her generalization, single motherhood is the root of social ills in America, takes the inductive reasoning too far. We could point to many, many examples of single mothers who raise well adjusted and successful children who contribute to society in positive ways. Similarly, we could find many mothers who remain married to the same person but are terrible mothers who raise troublemakers. Moreover, readers might question whether being single is the reason a mother does outrageous things, and whether people inflict social ills on America solely because they had a bad mother. In either instance, couldn’t other factors be at play?

Despite this example, we need inductive reasoning because it is how we reach many conclusions in our everyday life. If we didn’t use inductive reasoning, we would make the same mistakes again and again. Inductive reasoning is at the heart of the scientific method, which demands that we create or observe specific examples to reach conclusions; it’s how we discover theories and reach conclusions about how the world works. Scientists are always ready to revise a theory or a conclusion if new evidence comes along to call the theory or discussion into question. They also subject their conclusions to others who can view the logical critically and point out weaknesses that need to be addressed.

In your own arguments, you, too, will reach conclusions using both inductive and deductive. These are the only ways we come to conclusions, so in looking at your own arguments, you need to determine how you arrived at the conclusions you’re presenting. What makes you think that your claims are valid or true? Your argument should present the specific reasoning you used to come to the conclusions you present.

When observing or making inductive arguments, it is important to get your evidence from many different areas, judge it carefully, and acknowledge the flaws. Inductive arguments must be judged by the quality of the evidence, since the conclusions are drawn directly from a body of compiled work. When making deductive arguments, you need to identify the premises on which your argument rests and determine whether your conclusions truly grow out of those premises. Does your audience share your unstated assumptions? Do you need to be more explicit about your premises?

The Aristotelian Appeals

Another way to think about making strong arguments is to understand the Aristotelian Appeals. The Greek philosopher Aristotle lived from 384–322 BC, but we still apply his theories on how arguments work. “The appeals” offer a lesson in rhetoric that sticks with most students long after their class has ended. Perhaps it is the rhythmic quality of the words (ethos, logos, pathos) or simply the usefulness of the concept. Aristotle imagined logos, ethos, and pathos as three kinds of “artistic proof.” Essentially, they highlight three ways to appeal to or persuade an audience: “(1) to reason logically, (2) to understand human character and goodness in its various forms, (3) to understand emotions” (Honeycutt 1356a I i).

While Aristotle and others did not explicitly dismiss emotional and character appeals, they found the most value in logic. Contemporary rhetoricians and argumentation scholars, however, recognize the power of emotions to sway us. Even the most stoic individuals have some emotional threshold over which no logic can pass. For example, we can seldom be reasonable when faced with a crime against a loved one, a betrayal, or the face of an adorable baby.

The easiest way to differentiate the appeals is to imagine selling a product based on them. Until recently, car commercials offered a prolific source of logical, ethical, and emotional appeals.

| Aristotelian Appeal |

Definition | The Car Commercial |

|---|---|---|

| Logos | Using logic as proof for an argument. For many students, this takes the form of numerical evidence. But as we have discussed above, logical reasoning is a kind of argumentation. | (Syllogism) Americans love adventure—Ford Escape allows for off-road adventure—Americans should buy a Ford Escape, or: The Ford Escape offers the best financial deal. |

| Ethos | Calling on particular shared values (patriotism), respected figures of authority (Martin Luther King Jr.), or one’s own character as a method for appealing to an audience. | Eco-conscious Americans drive a Ford Escape, or: [Insert favorite celebrity] drives a Ford Escape. |

| Pathos | Using emotionally driven images or language to sway your audience. | Images of a pregnant woman being safely rushed to a hospital. Flash to two car seats in the back seat. Flash to family hopping out of their Ford Escape and witnessing the majesty of the Grand Canyon, or: After an image of a worried mother watching her sixteen-year-old daughter drive away: “Ford Escape takes the fear out of driving.” |

The appeals are part of everyday conversation, even if we do not use the Greek terminology. Understanding the appeals helps us make better rhetorical choices in designing our arguments. If you think about the appeals as a choice, their value is clear.

Toulmin: Dissecting the Everyday Argument

A more contemporary philosopher, Stephen Toulmin, studied the arguments we make in our everyday lives. He developed his method out of frustration with logicians (philosophers of argumentation) who studied argument in a vacuum or through mathematical formulations:

All A are B. All B are C.

Therefore, all A are C. (van Eemeren et al. 131)

Instead, Toulmin views argument as it appears in a conversation, in a letter, or in some other context because real arguments are much more complex than the syllogisms that make up the bulk of Aristotle’s logical program. Toulmin offers the contemporary writer/reader a way to map an argument. The result is a visualization of the argument process. This map comes complete with vocabulary for describing the parts of an argument. The vocabulary allows us to see the contours of the landscape—the winding rivers and gaping caverns. One way to think about a “good” argument is that it is a discussion that hangs together, a landscape that is cohesive (we can’t have glaciers in our desert valley). Sometimes we miss the faults of an argument because it sounds good or appears to have clear connections between the statement and the evidence when in truth the only thing holding the argument together is a lovely sentence or an artistic flourish.

For Toulmin, argumentation is an attempt to justify a statement or a set of statements. The better the demand is met, the higher the audience’s appreciation. Toulmin’s vocabulary for the study of argument offers labels for the parts of the argument to help us create our map.

| Terms | Definition |

|---|---|

| Claim | The basic standpoint presented by a writer/speaker. |

| Data | The evidence that supports the claim. |

| Warrant | The justification for connecting particular data to a particular claim. The warrant also makes clear the assumptions underlying the argument. |

| Backing | Additional information is required if the warrant is not clearly supported. |

| Rebuttal | Conditions or standpoints that point out flaws in the claim or alternative positions. |

| Qualifiers | Terminology that limits a standpoint. Examples include applying the following terms to any part of an argument: sometimes, seems, occasionally, none, always, never, and so on. |

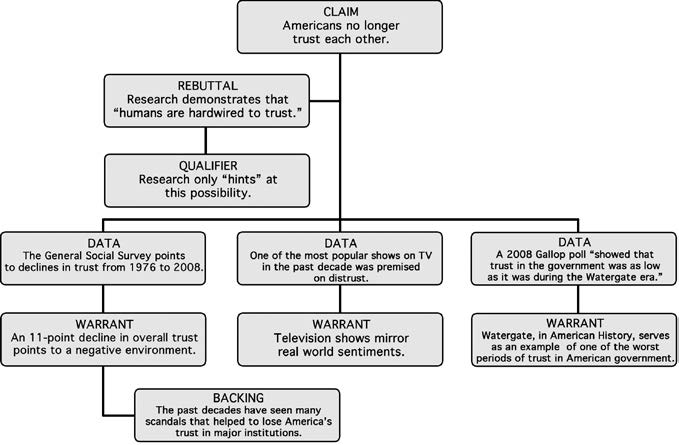

The following paragraphs come from an article reprinted in Utne Reader by Pamela Paxton and Jeremy Adam Smith titled “Not Everyone Is Out to Get You.” Charting this excerpt helps us understand some of the underlying assumptions found in the article.

That was the slogan of The X-Files, the TV drama that followed two FBI agents on a quest to uncover a vast government conspiracy. A defining cultural phenomenon during its run from 1993 to 2002, the show captured a mood of growing distrust in America.

Since then, our trust in one another has declined even further. In fact, it seems that “Trust no one” could easily have been America’s motto for the past 40 years—thanks to, among other things, Vietnam, Watergate, junk bonds, Monica Lewinsky, Enron, sex scandals in the Catholic Church, and the Iraq war.

The General Social Survey, a periodic assessment of Americans’ moods and values, shows an 11-point decline from 1976–2008 in the number of Americans who believe other people can generally be trusted. Institutions haven’t fared any better. Over the same period, trust has declined in the press (from 29 to 9 percent), education (38–29 percent), banks (41 percent to 20 percent), corporations (23–16 percent), and organized religion (33–20 percent). Gallup’s 2008 governance survey showed that trust in the government was as low as it was during the Watergate era.

The news isn’t all doom and gloom, however. A growing body of research hints that humans are hardwired to trust, which is why institutions, through reform and high performance, can still stoke feelings of loyalty, just as disasters and mismanagement can inhibit it. The catch is that while humans want, even need, to trust, they won’t trust blindly and foolishly (44–45).

Fig 9.5 demonstrates one way to chart the argument that Paxton and Smith make in “Not Everyone Is Out to Get You.” The remainder of the article offers additional claims and data, including the final claim that there is hope for overcoming our collective trust issues. The chart helps us see that some of the warrants, in a longer research project, might require additional support. For example, the warrant that TV mirrors real life is an argument and not a fact that would require evidence.

Charting your own arguments and others helps you visualize the meat of your discussion. All the flourishes are gone and the bones revealed. Even if you cannot fit an argument neatly into the boxes, the attempt forces you to ask important questions about your claim, your warrant, and possible rebuttals. By charting your argument, you are forced to write your claim in a succinct manner and admit, for example, what you are using for evidence or what assumption (warrant) undergirds the evidence. Charted, you can see if your evidence is scanty, if it relies too much on one kind of evidence over another, and if it needs additional support. This charting might also reveal a disconnect between your claim and your warrant or cause you to reevaluate your claim altogether.

Conclusion

Even though our current media and political climate do not call for good argumentation, the guidelines for finding and creating it abound. There are many organizations such as America Speaks that are attempting to revive quality, ethical deliberation. On the personal level, each writer can be more deliberate in their argumentation by choosing to follow some of these methodical approaches to ensure the soundness and general quality of their argument. The above models offer the possibility that we can imagine modes of argumentation other than war. These approaches see argument as a conversation that requires constant vigilance and interaction by participants. Argument as conversation, as new metaphor for public deliberation, has possibilities.

Note

Thanks to Nina Paley for giving permission to use her cartoon for figure 9.1 under Creative Commons licensing, free of charge. Please see Paley’s great work at ninapaley.com.

Works Cited

Coulter, Ann. Guilty: Liberal “Victims” and Their Assault on America. Crown Forum, 2009.

Crowley, Sharon, and Debra Hawhee. Ancient Rhetorics for Contemporary Students. 4th ed., Pearson/Longman, 2009.

Fish, Stanley. “Democracy and Education.” New York Times, 22 July 2007, fish.blogs.nytimes.com/2007/07/22/democracy-and-education.

Honeycutt, Lee. Aristotle’s Rhetoric: A Hypertextual Resource Compiled by Lee Honeycutt, 21 June 2004, kairos.technorhetoric.net/stasis/2017/honeycutt/aristotle/index.html.

Lakoff, George, and Mark Johnson. Metaphors We Live By. U of Chicago P, 1980.

Murphy, James. Quintilian on the Teaching and Speaking of Writing. Southern Illinois UP, 1987.

Paxton, Pamela, and Jeremy Adam Smith. “Not Everyone Is Out to Get You.” Utne Reader, Sept.–Oct. 2009, pp. 44–45.

“Plato, The Dialogues of Plato, vol. 1 [387 AD].” Online Library of Liberty, 5 May 2010, oll.libertyfund.org/index.php?option=com_ staticxt&staticfile=show.php%3Ftitle=111&layout=html#chapt er_39482.