2 A Review of Essays and Paragraphs

Learning Objectives

- Write a clear thesis statement that unifies your essay

- Organize sentences around a topic sentence in a body paragraph

- Create smooth transitions in a paragraph

Download and/or print this chapter: Reading, Thinking, and Writing for College – Ch. 2

Basic Essay Structure

Most likely, if you’re a first-semester college student, the last time you had to write an essay was in high school. High school essay writing typically emphasizes the five-paragraph essay: introduction, three body paragraphs, and a conclusion. If you’ve been out of high school for a while or if you struggled with essay writing in high school, this chapter will help you review this basic structure, which can serve as a foundation for your college-level essays.

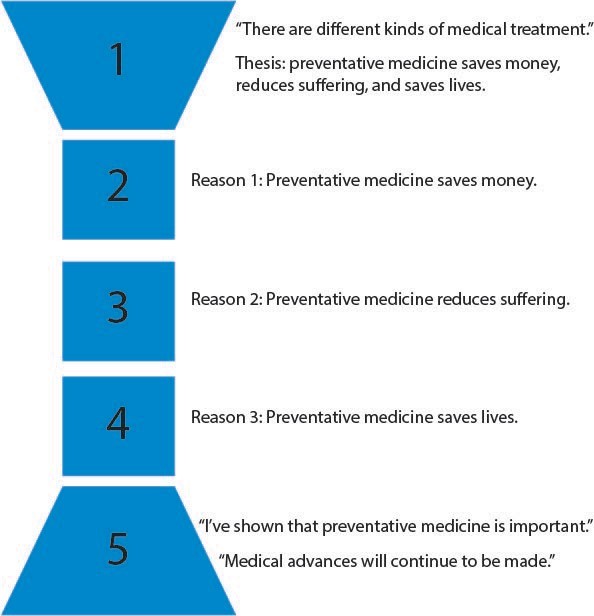

The skills that go into the five-paragraph essay are indispensable. The outline below in Figure 3.1 is probably what you’ve been taught about essay structure. The introduction starts general and gradually narrows to a thesis, which readers expect to find at the very end of that paragraph. In this format, the thesis uses that magic number of three: three reasons why a statement is true. Each of those reasons is explained and justified in the three body paragraphs, and then the conclusion restates the thesis before gradually getting broader. This format is easy for readers to follow, and it helps writers to organize their points and the evidence that goes with them. That’s why you learned this format.

Figure 3.1 The traditional five-paragraph essay structure

All that time you spent mastering the five-paragraph form in Figure 3.1 was not wasted. In a college-level writing class, though, you’ll be expected to move beyond this basic formula. The video below explains the basic five-paragraph essay structure and how you will be expected to develop a more sophisticated approach to writing for your college classes.

The Thesis

As the video explained, the body paragraphs in your essays are supposed to develop your thesis, and the thesis, as you may recall, is the “main idea” or “main claim” of your essay. For college-level writing, though, the thesis usually does more than simply announce the main idea of your essay. A good thesis is an original idea or opinion that you’ve developed by studying, reading, and thinking critically about your topic. A good thesis statement conveys your purpose for writing and previews what’s coming in your essay. In addition, a college-level thesis meets these criteria:

- A good thesis is non-obvious. High school teachers needed to make sure that you and all your classmates mastered the basic form of the academic essay. Thus, they were mostly concerned that you had a clear and consistent thesis, even if it was something obvious like “sustainability is important.” A thesis statement like that has a wide-enough scope to incorporate several supporting points and concurring evidence, enabling the writer to demonstrate his or her mastery of the five-paragraph form. Good enough for high school! When they can, high school teachers nudge students to develop arguments that are less obvious, more original, and more engaging. College instructors, on the other hand, always expect you to produce something more sophisticated and specific. They also want you to go beyond the obvious and offer your original thinking about a topic. To write a good thesis, therefore, most writers revise their thesis statements as they work on their essays. Writing about a topic helps them discover more interesting, specific points to make about the topic. A good thesis reflects good critical thinking and an original perspective.

- A good thesis is arguable. In everyday life, “arguable” is often used as a synonym for “controversial.” For a thesis, though, “arguable” doesn’t mean highly opinionated, and the goal of an academic essay isn’t necessarily to convert every reader to your way of thinking. Rather, a good thesis offers readers a new idea, a new perspective, or an opinion about a topic. The need to be arguable dovetails with the need to be specific: only when we have deeply explored a problem can we arrive at an original and specific argument that legitimately needs 3, 5, 10, or 20 pages to explain and justify. In that way, a good thesis sets an ambitious agenda for a paper.

- A good thesis is specific. You don’t want to set too ambitious an agenda, though! Some student writers fear that they won’t have enough to write about if they present a specific thesis, so they attempt to cover too much. A thesis like “sustainability is important” may seem like a great thesis because one could write all of the reasons for why it’s important, but the vague language invites a superficial discussion of a complicated topic. A thesis like “sustainability policies will inevitably fail if they do not incorporate social justice” limits the scope of the discussion, which in turn means that the essay itself will provide a more in-depth discussion of sustainability policies. It could even be more specific: which sustainability policies?

How do you produce a thesis that meets these criteria? Many instructors and writers find useful a metaphor based on this passage by Oliver Wendell Holmes, Sr.[1]

There are one-story intellects, two-story intellects, and three-story intellects with skylights. All fact collectors who have no aim beyond their facts are one-story men. Two-story men compare, reason, generalize using the labor of fact collectors as their own. Three-story men idealize, imagine, predict—their best illumination comes from above the skylight.

One-story theses state inarguable facts. Two-story theses bring in an arguable (interpretive or analytical) point. Three-story theses nest that point within its larger, compelling implications.[2]

One-story theses state inarguable facts. Two-story theses bring in an arguable (interpretive or analytical) point. Three-story theses nest that point within its larger, compelling implications.[2]

The biggest benefit of the three-story metaphor is that it describes a process for building a thesis. To build the first story, you first have to get familiar with the complex, relevant facts surrounding the problem or question. You have to be able to describe the situation thoroughly and accurately. Then, with that first story built, you can layer on the second story by formulating the insightful, arguable point that animates the analysis. That’s often the most effortful part: brainstorming, elaborating and comparing alternative ideas, finalizing your point. With that specified, you can frame up the third story by articulating why the point you make matters beyond its particular topic or case.

For example, imagine you have been assigned a paper about the impact of online learning in higher education. You would first construct an account of the origins and multiple forms of online learning and assess research findings about its use and effectiveness. If you’ve done that well, you’ll probably come up with a well considered opinion that wouldn’t be obvious to readers who haven’t looked at the issue in depth. Maybe you’ll want to argue that online learning is a threat to the academic community. Or perhaps you’ll want to make the case that online learning opens up pathways to college degrees that traditional campus-based learning does not. In the course of developing your central, argumentative point, you’ll come to recognize its larger context; in this example, you may claim that online learning can serve to better integrate higher education with the rest of society, as online learners bring their educational and career experiences together.

EXAMPLE 1

To outline this example:

- First story: Online learning is becoming more prevalent and takes many different forms.

- Second story: While most observers see it as a transformation of higher education, online learning is better thought of an extension of higher education in that it reaches learners who aren’t disposed to participate in traditional campus-based education.

- Third story: Online learning appears to be a promising way to better integrate higher education with other institutions in society, as online learners integrate their educational experiences with the other realms of their life, promoting the freer flow of ideas between the academy and the rest of society.

EXAMPLE 2

Here’s another example of a three-story thesis:[3]

- First story: Edith Wharton did not consider herself a modernist writer, and she didn’t write like her modernist contemporaries.

- Second story: However, in her work we can see her grappling with both the questions and literary forms that fascinated modernist writers of her era. While not an avowed modernist, she did engage with modernist themes and questions.

- Third story: Thus, it is more revealing to think of modernism as a conversation rather than a category or practice.

EXAMPLE 3

Here’s one more example:

- First story: Scientists disagree about the likely impact in the U.S. of the light brown apple moth (LBAM), an agricultural pest native to Australia.

- Second story: Research findings to date suggest that the decision to spray pheromones over the skies of several southern Californian counties to combat the LBAM was poorly thought out.

- Third story: Together, the scientific ambiguities and the controversial response strengthen the claim that industrial-style approaches to pest management are inherently unsustainable.

A thesis statement that stops at the first story isn’t usually considered a thesis. A two-story thesis is usually considered competent, though some two-story theses are more intriguing and ambitious than others. A thoughtfully crafted and well informed three-story thesis puts the author on a smooth path toward an excellent paper.

Basic Paragraph Structure

Think back to when you first learned to write paragraphs. Maybe you learned that paragraphs are supposed to have a certain number of sentences, or maybe you learned an acronym for what a paragraph is, such as the P. I. E. paragraph format (P=point, I=information, E=explanation). Some students learn to write paragraphs that follow certain patterns, such as narrative or compare/contrast. Whatever you learned about paragraphs, you probably remember that paragraphs need to include a topic sentence, supporting information, smooth transitions from one sentence to the next, and a concluding sentence. Take a moment to review these elements of all paragraphs.

Topic Sentences

The main idea of the paragraph is stated in the topic sentence. A good topic sentence does the following:

- introduces the rest of the paragraph

- contains both a topic and an idea or opinion about that topic

- is clear and easy to follow

- does not include supporting details

- engages the reader

For example:

Development of the Alaska oil fields threaten the already-endangered Northern Sea Otters.

This sentence introduces the topic and the writer’s opinion. After reading this sentence, a reader might reasonably expect the writer to go on to provide supporting details and facts about what the threat is. The sentence is clear and the word choice is interesting.

Here is another example:

Many major league baseball players have cheated by “corking” their bats.

Again, the topic and opinion are clear and specific, the details (what is corking? which players?) are saved for later, and the word choice is powerful.

Now look at this example:

I think everyone should be able to take a pet, especially service pets, to work because they provide comfort, and the potential problems they might cause can be eliminated if companies develop good policies.

Even though the topic and opinion are evident, the sentence is not focused or specific. It’s not likely that the writer could provide enough support to argue that every place of employment, from McDonald’s to a law office, should allow any kind of pets, from service dogs to parakeets. Furthermore, the writer is also offering two points that need to be discussed: pets provide comfort and pets don’t cause problems. Most likely, each of these points needs to be addressed in a separate paragraph.

The writer could revise the topic sentence into two topic sentences:

- Being able to bring a dog or cat to the office can be comforting to people who work at a desk from 9:00-5:00.

- Specific policies and practices can eliminate some of the problems that might occur if employees are allowed to bring pets to the office.

These two paragraphs might appear in an essay arguing that people should be able to take their pets in public more often. The topic sentence would clearly support such a thesis, which would need many more paragraphs of support.

Typically, you should place the topic sentence at the beginning of the paragraph. In college and business writing, readers often lose patience if they are unable to quickly grasp what the writer is trying to say. Topic sentences make the writer’s basic point easy to locate and understand.

Developing the Topic Sentence

The body of a paragraph contains supporting details to help explain, prove, or expand the topic sentence. Often, in attempting to support a topic sentence with plenty of supporting details, writers discover that they need two paragraphs to support one point. For example, consider the following topic sentence, which might appear in an essay about reforming social security.

For many older Americans, retiring at 65 is not option.

Supporting sentences could include a few of the following details:

- Fact: Many families now rely on older relatives for financial support.

- Reason: The life expectancy for an average American is continuing to increase.

- Statistic: More than 20 percent of adults over age 65 are currently working or looking for work in the United States.

- Quotation: Senator Ted Kennedy once said, “Stabilizing Social Security will help seniors enjoy a well-deserved retirement.”

- Example: Last year, my grandpa took a job with Walmart because he was forced to retire early.

The personal example might be something the writer wants to expand upon in a separate paragraph, one that tells a short story about the grandfather’s decision to go back to work after retiring. The point, however, would be expressed in the topic sentence from the previous paragraph.

Sometimes, though, the topic sentence presents one idea but in presenting the supporting details, the writer gets off topic. A topic sentence guides the reader by signposting what the paragraph is about, so the rest of the paragraph should relate to the topic sentence. Can you spot the sentence in the following paragraph that does not relate to the topic sentence?

Health policy experts note that opposition to wearing a face mask during the COVID-19 pandemic is similar to opposition to the laws governing alcohol use. For example, some people believe drinking is an individual’s choice, not something the government should regulate. However, when an individual’s behavior impacts others–as when a drunk driver is involved in a fatal car accident–the dynamic changes. Seat belts are a good way to reduce the potential for physical injury in car accidents. Opposition to wearing a face mask during this pandemic is not simply an individual choice; it is a responsibility to others.

If you guessed the sentence that begins “Seat belts are” doesn’t belong, you are correct. It does not support the paragraph’s topic: opposition to regulations. If a point isn’t connected to the topic sentence, the writer should tie it in or take it out. Sometimes, the point needs to be included in another paragraph, one with a different topic sentence.

Concluding Sentences

A strong concluding sentences draws together the ideas raised in the paragraph and can set the readers up for a good transition into the next paragraph. A concluding sentence reminds readers of the main point without repeating the same words.

Concluding sentences can do any of the following:

- summarize the paragraph

- draw a conclusion based on the information in the paragraph

- make a prediction, suggestion, or recommendation about the information

For example, in the paragraph above about wearing face masks, the concluding sentence summarizes the key point: responsibility to others. The next paragraph in the essay might begin by stating something like, “Not all face masks, however, will protect people to the same degree.” The topic sentence connects the new point (which face masks are best at protecting others) with the point made in the previous paragraph (wearing face masks is a way to protect others).

Transitions

In a series of paragraphs, such as in the body of an essay, concluding sentences are often replaced by transitions. Transitions are words or phrases that help the reader move from one idea to the next, whether within a paragraph or between paragraphs. For example:

I am going to fix breakfast. Later, I will do the laundry.

“Later” transitions us from the first task to the second one. “Later” shows a sequence of events and establishes a connection between the tasks.

Look at this paragraph:

There are numerous advantages to owning a hybrid car. For example, they get up to 35 percent more miles to the gallon than a fuel-efficient, gas-powered vehicle. Also, they produce very few emissions during low speed city driving. Because they do not require gas, hybrid cars reduce dependency on fossil fuels, which helps lower prices at the pump. Given the low costs and environmental benefits of owning a hybrid car, it is likely that many people will buy hybrids in the future.

Each of the bold words is a transition. Transitions organize the writer’s ideas and keep the reader on track. They make the writing flow more smoothly and connect ideas.

Beginning writers tend to rely on ordinary transitions, such as “first” or “in conclusion.” There are more interesting ways to tell a reader what you want them to know. Here are some examples:

| Purpose | Transition Words and Phrases |

|---|---|

| to show a sequence of events | eventually, finally, previously, next, then, later on |

| to show additional information | also, in addition to, for example, for instance |

| to show consequences | therefore, as a result, because, since |

| to show comparison or contrast | however, but, nevertheless, although |

These words have slightly different meanings so don’t just substitute one that sounds better to you. Use your dictionary to be sure you are saying what you mean to say.

Paragraph Length

How long should a paragraph be? The answer is “long enough to explain your point.” A paragraph can be fairly short (two or three sentences) or, in a complex essay, a paragraph can be a page long. Most paragraphs contain three to six supporting sentences, but as long as the writer maintains close focus on the topic and does not ramble, a long paragraph is acceptable in college-level writing. In some cases, even when the writer stays focused on the topic and doesn’t ramble, a long paragraph will not hold the reader’s interest. In such cases, divide the paragraph into two or more shorter paragraphs, adding a transitional word or phrase.

In an essay, a research paper, or a book, paragraphs separate ideas into logical, manageable chunks. Effective writers begin a new paragraph for each new idea they introduce. If paragraphs are still a mystery to you, or if you struggle to determine when to begin a new paragraph or how to organize sentences within a paragraph, you’re not alone. Saying what a paragraph is may not be that difficult, but writing a good paragraph is. When writing a first draft of an essay, it’s highly unlikely that you will write perfect topic sentences, strong support, and excellent concluding sentences for each paragraph or that you will organize all of the information in your essay so that it’s unified around specific topic sentences. That’s why good writers revise. They know that they will need to delete, add, and re-word each of their paragraphs so that they present their ideas in a clear and forceful manner.

Key Takeaways

- Most college writing requires you to go beyond the basic five-paragraph essay structure.

- A thesis statement needs to be sophisticated and focused.

- Topic sentences express the main idea of the paragraph and usually appear at the beginning of a paragraph

- Support for the topic sentences include details, examples, quotes, statistics, and facts.

- Concluding sentences wrap-up the points made in the paragraph.

- Transitional words and phrases show how ideas relate to one another and move the reader on to the next point.

- The thesis and paragraphs in a first draft of an essay will always need to be revised

- Oliver Wendell Holmes Sr., The Poet at the Breakfast Table (New York: Houghton & Mifflin, 1892). ↵

- The metaphor is extraordinarily useful even though the passage is annoying. Beyond the sexist language of the time, it displays condescension toward “fact-collectors” which reflects a general modernist tendency to elevate the abstract and denigrate the concrete. In reality, data-collection is a creative and demanding craft, arguably more important than theorizing ↵

- Drawn from Jennifer Haytock, Edith Wharton and the Conversations of Literary Modernism (New York: Palgrave-MacMillan, 2008). ↵