52 Reading Poetry

But let’s put you in this very concrete situation: You’re sitting down in front of a poem you’ve been asked to write about for this class. What do you do?

Learning to read a new poem is like learning to play a new song on a guitar. So try this: Decide before you begin that you are going to read every poem at least three times. It’s important no matter how long the poem is.

Reading poems out loud is best. Read the poem the first time straight through, pronouncing each word. You’re not looking for meaning or sounds. You’re just familiarizing yourself with the words, allowing them to bend back the grass in your brain so that they’ll be easier to walk through the next time.

Read the second time for sound. Concentrate on how the sounds fall. Hit the rhymes, pick up on the rhythms, notice (but don’t dwell on) any interesting use of sounds in the poem.

Read slowly and smoothly. If you stumble through the poem the second time, read it again and again until you get to the point where you no longer stumble over sound.

Read the poem the third time for meaning. When you are reading for meaning, keep in mind two things.

- First (we say it again), the vast majority of poems are written in grammatically correct sentences. It will help you a lot if you know how to recognize a verb, a noun, and how to find them. And, if you know how to distinguish a subject from an object, you’re well on your way. If you go through the sentence from beginning to end and don’t understand it, look for the verb, find its subject and its object. Don’t confuse line ends with sentence ends or even with natural pauses. You’ll be tempted to pause at line endings. Realize that the pause may not come where it would come if the same sentence were presented as prose. Often the sense keeps going past the end of lines. It’s good practice to try to paraphrase the sentences of the poem one at a time.

- Second, it’s nearly always possible to see the poem as a story. So look for it. Even poems not generally considered to be narrative poems tell or suggest a story. Most poems have at least some of the basic elements of a story: characters, dramatic situation, setting, action. Ask yourself what story the poem seems to tell. As with most stories, a poem is likely to come to us in two distinct voices: the voice of the poet and the voice of the speaker of the poem (when we are talking about fiction, we use the terms “author” and “narrator”). Most students do not realize that the speaker of the poem is not the same as the author of the poem. And sometimes it’s true that this distinction does not matter. But in most cases, a poem is spoken by an unnamed “voice” created by the author for the particular purpose of the poem. The easiest way to show this is with an example.

Look at these stanzas from a poem about discovering a snake in the grass:

A narrow fellow in the grass

Occasionally rides;

You may have met him—did you not

His notice sudden is,

He likes a boggy acre,

A floor too cool for corn,

But when a boy and barefoot,

I more than once at noon

Have passed, I thought, a whiplash,

Unbraiding in the sun,

When stooping to secure it,

It wrinkled and was gone.

I’ve never met this fellow,

Attended or alone,

Without a tighter breathing,

And zero at the bone.[1]

This poem, by Emily Dickinson, relays the experience of a boy who was scared when he stooped down to pick up what he thought was the lash of a whip only to see it slither away. Dickinson was never a boy and may never have had the experience she writes about. Why she decided to narrate the poem from a boy’s point of view is something we can discuss. When we discuss the poem, we typically refer to the poet or voice(s) as the speaker or narrator in the poem.

However, what she does shows us is that we should not automatically assume that a poem or the facts it contains are autobiographical. If there is more than one speaker or voice in a poem then it’s important to hear all the voices.

- If you think the poem is a story and recognize the speaker (or narrator), and if you can paraphrase each of the sentences, you’ll have a very good handle on the verbal meaning of a poem.

- Don’t panic if this doesn’t work. Perhaps you’ve missed something—like an obscure meaning of a word, and the issue may not be yours at all. It may be that the poem resists this approach. This is when you need a guide.

- Poems were originally intended as communal, not individual, objects. And they are still best read in a community. If you don’t understand something, chances are your classmates don’t either. Speak up or write a discussion post!

Remember, while meaning (in the ordinary sense) is hardly ever the primary element in strong poetry, it’s always there. Any poem that simply puts the music at the service of the meaning is likely to be inferior for that reason. Language in which meaning is primary is plentiful enough. It’s simply not the case with poetry. In poetry the music itself is inseparable from the meaning.

Verbal meaning is important, and often is necessary for a reader to be able to paraphrase a poem. But verbal meaning is never the whole. In good poems, musical meaning is not secondary. And poems exist that cannot be paraphrased. So when we think about what a poem is doing, we need to think about the music in addition to (or as part of) the meaning of a poem.

This really is not a strange concept. If I scream “I love you” through gritted teeth, the words won’t mean the same thing they mean if I say them softly on my knees handing you flowers. The meaning is not in the words alone.

Poetic Structure

Learning Objectives

Identify characteristic structuring principles in poetry

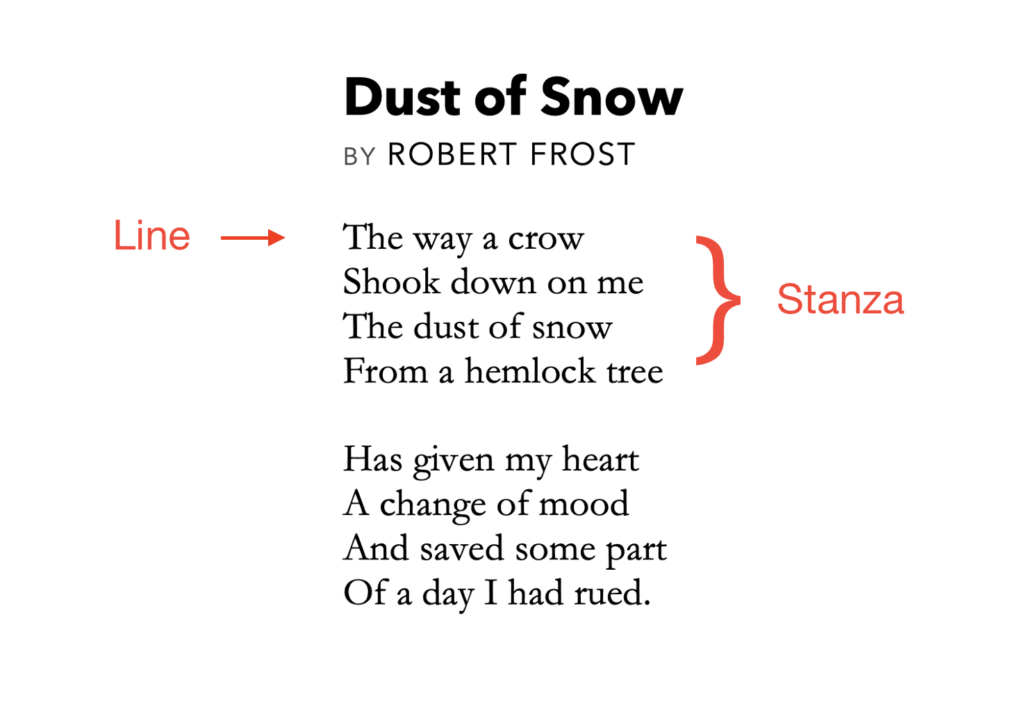

In the figure above, you will find eight lines and two stanzas. A line is a single row of words in a poem. A group of lines builds a stanza, which typically focuses on one thought, concept, or portion of a story. Stanzas are typically separated by extra space or a blank line. To draw a parallel to prose, one might think of poetry’s lines as sentences, and of its stanzas as paragraphs.

The words and syllables in a poem also play a key role in forming its structure. Poets frequently use rhyme, meaning that they choose words that contain corresponding sounds (ex: cat, hat, bat), which often appear at the ends of lines. Rhyming can add to the beauty of a poem by creating a pleasurable echo among lines. It also helps build the poem’s structure by unifying the lines so that they sound right together. A common misconception, however, is that all poems rhyme. Many do not follow a rhyme scheme, as we can see in examples like Maya Angelou’s “Caged Bird” and T.S. Eliot’s “Aunt Helen.” Rhyme is just one tool that poets might use to create their art, but it is not a required element.

Poets can also use meter to create aesthetic and structure in their work. “Meter” refers to the rhythm of a line, which depends on the number of syllables, and on the pattern of stressed and unstressed syllables in the line.

In following video from Oregon State University, pay attention to the difference between stressed and unstressed syllables:

As we can see, syllabic stress plays a major role in how we understand words in English. Consider the word “present.” You may have read that word as gift one receives for an occasion, or as current moment in time, in relation to “past” and “future.” If so, you placed the stress on the first syllable (PREH-zent). You may, however, have read the word as a verb that refers to the act of giving an award to someone. If so, you placed the stress on the second syllable (pre-ZENT). If you’re familiar with languages like Spanish, it may be helpful to think about the letters over which we place accent marks (habló vs. hablo). These accent marks indicate that a syllable should be stressed.

The pattern of stressed and unstressed syllables in a poem helps create a rhythm that readers can follow, much like the beat in a song. One can determine the meter by analyzing this pattern of syllables, which can be broken into “feet.” A foot refers to a group of syllables in a poem. A foot usually contains one stressed syllable and at least one unstressed syllable. The five most common types of feet are as follows, with “U” representing unstressed syllables, and “S” representing stressed syllables:

- trochee (S+U)

- iamb (U+S)

- dactyl (S+U+U)

- anapest (U+U+S)

- spondee (S+S)

Edgar Allen Poe’s “The Raven” is an example of trochaic meter (using trochees). The first line is highlighted to reflect the syllables in each trochee. The syllables that are highlighted in green are stressed, while those in blue are unstressed:

Once upon a midnight dreary, while I pondered, weak and weary,

Over many a quaint and curious volume of forgotten lore—

While I nodded, nearly napping, suddenly there came a tapping,

As of some one gently rapping, rapping at my chamber door.

“’Tis some visitor,” I muttered, “tapping at my chamber door—

Only this and nothing more.”

Lord Byron’s “She Walks in Beauty” is an example of iambic meter (using iambs). Like the previous example, syllables that are highlighted in green are stressed, while those in blue are unstressed:

She walks in beauty, like the night

Of cloudless climes and starry skies;

And all that’s best of dark and bright

Meet in her aspect and her eyes;

Thus mellowed to that tender light

Which heaven to gaudy day denies.

Both trochaic and iambic meters alternate between stressed and unstressed syllables, but the difference is the order in which they appear. In the examples above, Poe’s lines begin with stressed syllables, while Byron’s begin with unstressed ones.

The number of feet in a line also contributes to how we identify meter. If you have heard of “iambic pentameter” before, you have already encountered this type of identification. The first word refers to the stress patterns in the poem’s feet, while the second word refers to how many feet are in each line.

- one foot = monometer

- two feet = dimeter

- three feet = trimeter

- four feet = tetrameter

- five feet = pentameter

- six feet = hexameter

- seven feet = heptameter

- eight feet = octameter

So, if we look again at iambic pentameter, which is quite common in Shakespeare’s work, we know that the poem’s feet are iambs (U+S), and that there are five feet per line.

Just like rhyme, meter is a common tool that poets use to create structure, but some poems do not use it. When a poet writes without rhyme or meter, the poem is written in free verse. Langston Hughes’s “The Negro Speaks of Rivers” is an example of a free verse poem.

Poetic Devices

Learning Objectives

Identify poetic devices

In addition to structure, there are many devices that are hallmarks of poetry. Other writers sometimes use these devices in their prose, but they are much more common in poetry. There are many poetic devices, but the most common ones are:

- Imagery is illustration through language. The poet creates a mental image using words that appeal to the five senses.

- Alliteration is the repetition of a sound or letter in multiple words. The repeated sound or letter appears at the beginning of each word, and it is frequently a consonant.

- Assonance, on the other hand, is the repetition of vowel sounds in multiple words. These vowel sounds appear within or at the end of each word.

- Personification is when a writer describes an inanimate object using anthropomorphic (human-like) terms. The object cannot literally perform or possess these human actions and traits, but personification allows readers to more closely imagine what the writer is describing.

- Metaphor is a comparison between two things that are unrelated to one another.

- Simile is a metaphor that uses the words “like” or “as.”

- Onomatopoeia is when a word reflects the sound to which it refers. The word “buzz” mimics the “bzzz” sound of a bee as you say it aloud.

- Repetition is the use of the same word many times in a poem or other text. The author emphasizes the importance of the word by repeating it.

Let’s see these terms in action in the following excerpts:

Then from the moorland, by misty crags,

with God’s wrath laden, Grendel came.

The monster was minded of mankind now

sundry to seize in the stately house.

Under welkin he walked, till the wine-palace there, gold-hall of men, he gladly discerned,

flashing with fretwork.–Beowulf trans. by Frances B. Grummere

This translation of Beowulf uses alliteration. The first line repeats “M” sounds, the second repeats “G” sounds, and so on. Try reading it aloud to hear how alliteration contributes to the rhythm of the poem. Stress the syllables that contain the repeated sounds, and you might be able to hear a beat something like the heavy footsteps of the monster, Grendel.

When day comes we ask ourselves,

where can we find light in this never-ending shade?

The loss we carry,

a sea we must wade.

We’ve braved the belly of the beast,

We’ve learned that quiet isn’t always peace,

and the norms and notions

of what just is

isn’t always just-ice.

And yet the dawn is ours

before we knew it.

Somehow we do it.“The Hill We Climb” by Amanda Gorman

Gorman’s poem uses assonance. Pay close attention to the vowel sounds, and you will notice that many of them mimix one another. Examples include “never” and “ending”; “shade” and “wade”; “beast” and “peace”; and “norms” and “notions.”

Alliteration and assonance can help set a mood depending on which sounds they accentuate. The Bouba-Kiki effect speaks to this possibility in an intriguing way. Studies related to this phenomenon have revealed that people frequently associate certain sounds with types of images and features. Take a look at the two shapes below, and guess which one is named Bouba, and which is named Kiki.

Most often, people associate the shape on the right with the word “Bouba,” and the one on the left with “Kiki.” It appears that some sounds feel sharp and jagged, while others feel round and smooth. How do you think these associations might impact the mood of an alliterated poem?

I wandered lonely as a cloud

That floats on high o’er vales and hills,

When all at once I saw a crowd,

A host, of golden daffodils;

Beside the lake, beneath the trees,

Fluttering and dancing in the breeze.-“I Wandered Lonely as a Cloud” by William Wordsworth

The excerpt above uses simile, imagery, and personification. The narrator’s comparison between himself and a cloud in the first line appears as a simile: “lonely as a cloud.” The presence of the word “as” assures readers that the phrase is a simile, rather than a metaphor. The imagery appeals to readers’ senses of sight. One can picture the golden color and vast expanse of the daffodils based on Wordsworth’s words. Personification contributes to this image by making the daffodils “dance.” This action carries a happy, carefree type of movement that would not have been present had Wordworth used a verb like “shuddered” or “jerked.”

How they tinkle, tinkle, tinkle,

In the icy air of night!

While the stars that oversprinkle

All the heavens, seem to twinkle

With a crystalline delight;

Keeping time, time, time,

In a sort of Runic rhyme,

To the tintinabulation that so musically wells

From the bells, bells, bells, bells,

Bells, bells, bells—

From the jingling and the tinkling of the bells.– “The Bells” by Edgar Allen Poe

Poe uses plenty of onomatopoeia and repetition in this poem. Words like “tinkle” and “jingling” mimic the sounds a bell might make. Through the words themselves, we hear the bells. The repetition of the words “time” and “bells” contribute to the rhythm of the poem, perhaps reflecting the repeating sounds of the bells. What else might these poetic devices contribute to “The Bells”?

As we can see, poetic devices are just like the other “tools” we discussed in our last section; poets can use them to alter the aesthetic of their work, but they are not required in order for a text to qualify as a poem. This often means that poets will use different combinations of poetic devices to create beauty, mood, and complex meaning in their writing.

- We’ve cut out about half the poem to make the point more obvious. If you want to read the whole poem, you can find it here: http://www.poetryfoundation.org/poem/180204 ↵