20 Portfolio Reflection: Your Growth as a Writer

Portfolio Reflection: Your Growth as a Writer

Introduction

Reflecting on your work is an important step in your growth as a writer. Reflection allows you to recognize the ways in which you have mastered some skills and have addressed instances when your intention and execution fail to match. By recognizing previous challenges and applying learned strategies for addressing them, you demonstrate improvement and progress as a writer. This kind of reflection is an example of recursive. At this point in the semester, you know that writing is a recursive process: you prewrite, you write, you revise, you edit, you reflect, you revise, and so on. In working through a writing assignment, you learn and understand more about particular sections of your draft, and you can go back and revise them. The ability to return to your writing and exercise objectivity and honesty about it is one of skills you have practiced during this journey. You are now able to evaluate your own work, accept another’s critique of your writing, and make meaningful revisions.

In this chapter, you will review your work from earlier chapters and write a reflection that captures your growth, feelings, and challenges as a writer. In your reflection, you will apply many of the writing, reasoning, and evidentiary strategies you have already used in other papers—for example, analysis, evaluation, comparison and contrast, problem and solution, cause and effect, examples, and anecdotes.

When looking at your earlier work, you may find that you cringe at those papers and wonder what you were thinking when you wrote them. If given that same assignment, you now would know how to produce a more polished paper. This response is common and is evidence that you have learned quite a bit about writing.

14.1 Thinking Critically about Your Semester

Learning Outcomes

By the end of this section, you will be able to:

- Reflect on and write about the development of composing processes and how those processes affect your work.

- Demonstrate honesty and objectivity in reflecting on written work.

You have written your way through a long semester, and the journey is nearly complete. Now is the time to step back and reflect on what you have written, what you have mastered, what skill gaps remain, and what you will do to continue growing and improving as a communicator. This reflection will be based on the work you have done and what you have learned during the semester. Because the subject of this reflection is you and your work, no further research is required. The information you need is in the work you have done in this course and in your head. Now, you will work to organize and transfer this information to an organized written text. Every assignment you have completed provides you with insight into your writing process as you think about the assignment’s purpose, its execution, and your learning along the way. The skill of reflection requires you to be critical and honest about your habits, feelings, skills, and writing. In the end, you will discover that you have made progress as a writer, perhaps in ways not yet obvious.

14.2 Glance at Genre: Purpose and Structure

Learning Outcomes

By the end of this section, you will be able to:

- Identify conventions of reflection regarding structure, paragraphing, and tone.

- Articulate how genre conventions are shaped by purpose, culture, and expectation.

- Adapt composing processes for a variety of technologies and modalities.

Reflective writing is the practice of thinking about an event, an experience, a memory, or something imagined and expressing its larger meaning in written form. Reflective writing comes from the author’s specific perspective and often contemplates the way an event (or something else) has affected or even changed the author’s life.

Areas of Exploration

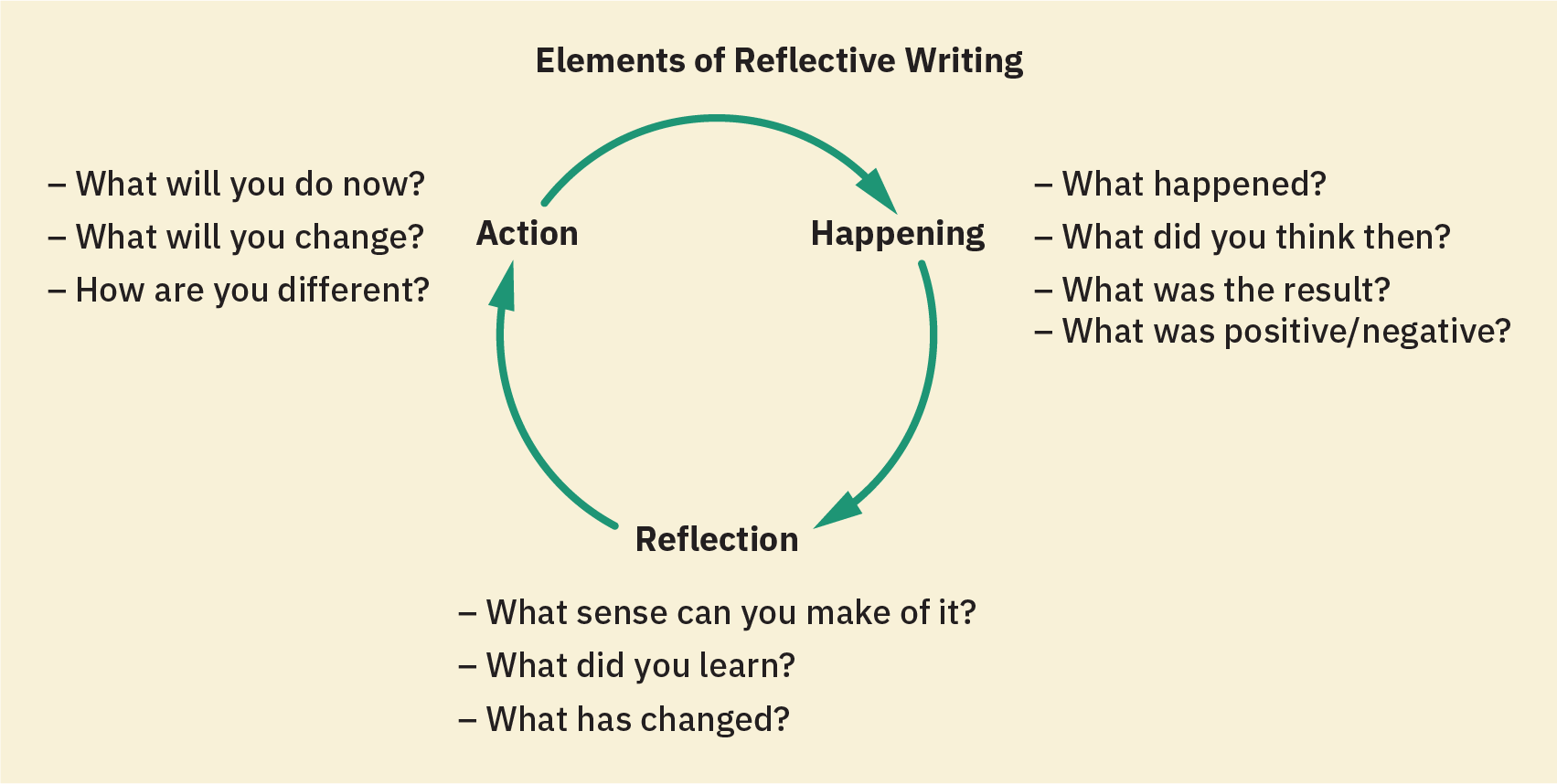

When you write a reflective piece, consider three main areas of exploration as shown in Figure 14.3. The first is the happening. This area consists of the events included in the reflection. For example, you will be examining writing assignments from this course. As you describe the assignments, you also establish context for the reflection so that readers can understand the circumstances involved. For each assignment, ask yourself these questions: What was the assignment? How did I approach the assignment? What did I do to start this assignment? What did I think about the assignment? If you think of other questions, use them. Record your answers because they will prove useful in the second area.

The second area is reflection. When you reflect on the happening, you go beyond simply writing about the specific details of the assignment; you move into the writing process and an explanation of what you learned from doing the work. In addition, you might recognize—and note—a change in your skills or way of thinking. Ask yourself these questions: What works effectively in this text? What did I learn from this assignment? How is this assignment useful? How did I feel when I was working on this assignment? Again, you can create other questions, and note your responses because you will use them to write a reflection.

The third area is action. Here, you decide what to do next and plan the steps needed to reach that goal. Ask yourself: What does (and does not) work effectively in this text? How can I continue to improve in this area? What should I do now? What has changed in my thinking? How would I change my approach to this assignment if I had to do another one like it? Base your responses to these questions on what you have learned, and implement these elements in your writing.

Figure 14.3 Elements of reflective writing (attribution: Copyright Rice University, OpenStax, under CC BY 4.0 license)

Format of Reflective Writing

Unlike thesis statements, which often come at the beginning of an essay, the main point of a piece of reflective writing may be conveyed only indirectly and nearly always emerges at the end, almost like an epiphany, or sudden realization. With this structure, readers are drawn into the act of reflecting and become more curious about what the writer is thinking and feeling. ln other words, reflective writers are musing, exploring, or wondering rather than arguing. In fact, reflective essays are most enlightening when they are not obviously instructive or assertive. However, even though reflective writing does not present an explicit argument, it still includes evidence and cohesion and provides lessons to be learned. As such, elements of persuasion or argument often appear in reflective essays.

Discovery through Writing

Keep in mind, too, that when you start to reflect on your growth as a writer, you may not realize what caused you to explore a particular memory. In other words, writers may choose to explore an idea, such as why something got their attention, and only by recalling the details of that event do they discover the reason it first drew their attention.

When you tell the story of your writing journey this semester, you may find that more was on your mind than you realized. The writing itself is one thing, but the meaning of what you learned becomes something else, and you may deliberately share how that second level, or deeper meaning or feeling, emerged through the act of storytelling. For example, in narrating a writing experience, you may step back, pause, and let readers know, “Wait a minute, something else is going on here.” An explanation of the new understanding, for both you and your readers, can follow this statement. Such pauses are a sign that connections are being made—between the present and the past, the concrete and the abstract, the literal and the symbolic. They signal to readers that the essay or story is about to move in a new and less predictable direction. Yet each idea remains connected through the structure of happenings, reflections, and actions.

Sometimes, slight shifts in voice or tone accompany reflective pauses as a writer moves closer to what is really on their mind. The exact nature of these shifts will, of course, be determined by the writer’s viewpoint. Perhaps one idea that you, as the writer, come up with is the realization that writing a position argument was useful in your history class. You were able to focus more on the material than on how to write the paper because you already knew how to craft a position argument. As you work through this process, continue to note these important little discoveries.

Your Writing Portfolio

As you recall, each chapter in this book has included one or more assignments for a writing portfolio. In simplest terms, a writing portfolio is a collection of your writing contained within a single binder or folder. A portfolio may contain printed copy, or it may be completely digital. Its contents may have been created over a number of weeks, months, or even years, and it may be organized chronologically, thematically, or qualitatively. A portfolio assigned for a class will contain written work to be shared with an audience to demonstrate your writing, learning, and skill progression. This kind of writing portfolio, accumulated during a college course, presents a record of your work over a semester and may be used to assign a grade. Many instructors now offer the option of, or even require, digital multimodal portfolios, which include visuals, audio, and/or video in addition to written texts. Your instructor will provide guidelines on how to create a multimodal portfolio, if applicable. You can also learn more about creating a multimodal portfolio and view one by a first-year student.

Key Terms

As you begin crafting your reflection, consider these elements of reflective writing.

Analysis: When you analyze your own writing, you explain your reasoning or writing choices, thus showing that you understand your progress as a writer.

Context: The context is the circumstances or situation in which the happening occurred. A description of the assignment, an explanation of why it was given, and any other relevant conditions surrounding it would be its context.

Description: Providing specific details, using figurative language and imagery, and even quoting from your papers helps readers visualize and thus share your reflection. When describing, writers may include visuals if applicable.

Evaluation: An effective evaluation points out where you faltered and where you did well. With that understanding, you have a basis to return to your thoughts and speculate about progress you will continue to make in the future.

Observation: Observation is a close look at the writing choices you made and the way you managed the rhetorical situations you encountered. When observing, be objective, and pay attention to the more and less effective parts of your writing.

Purpose: By considering the goals of these previous assignments, you will be better equipped to look at them critically and objectively to understand their larger use in academia.

Speculation: Speculation encourages you to think about your next steps: where you need to improve and where you need to stay sharp to avoid recurring mistakes.

Thoughts: Your thoughts (and feelings) before, during, and after an assignment can provide you with descriptive material. In a reflective essay, writers may choose to indicate their thoughts in a different tense from the one in which they write the essay itself.

When you put these elements together, you will be able to reflect objectively on your own writing. This reflection might include identifying areas of significant improvement and areas that still need more work. In either case, focus on describing, analyzing, and evaluating how and why you did or did not improve. This is not an easy task for any writer, but it proves valuable for those who aim to improve their skills as communicators.