7 Reading and Notetaking

About this Chapter

In this chapter we will explore two skills you probably think you already understand—reading and notetaking. But the goal is to make sure you’ve honed these skills well enough to lead you to success in college. By the time you finish this chapter, you should be able to do the following:

Discuss the way reading differs in college and how to successfully adapt to that change.

Demonstrate the usefulness of strong notetaking for college students.

Reading and consuming information are increasingly important today because of the amount of information we encounter. Not only do we need to read critically and carefully, but we also need to read with an eye to distinguishing fact from opinion and identifying solid sources. Reading helps us make sense of the world—from simple reminders to pick up milk to complex treatises on global concerns, we read to comprehend, and in so doing, our brains expand. An interesting study from Emory University in Atlanta, Georgia, used MRI scans to track the brain conductivity while participants were reading. The researchers assert that a biological change to your brain actually happens when you read, and it lingers. If you want to read the study, published in the journal Brain Connectivity, you can find it online at https://openstax.org/l/brainconnectivity.

In academic settings, as we deliberately work to become stronger readers and better notetakers, we are both helping our current situation and enhancing our abilities to be successful in the future. Seems like a win-win. Take advantage of all the study aids you have at hand, including human, electronic, and physical resources, to increase your performance in these crucial skill sets.

Why? You need to read. It improves your thinking, your vocabulary, and your ability to make connections between disparate parts, which are all parts of critical thinking. Educational researchers Anne Cunningham and Keith Stanovich discovered after extensive study with college students that “reading volume [how much you read] made a significant contribution to multiple measures of vocabulary, general knowledge, spelling, and verbal fluency.”

Research continues to assess and support the fact that one of the most significant learning skills necessary for success in any field is reading. You may have performed this skill for decades already, but learning to do it more effectively and practicing the skill consistently is critical to how well you do in all subjects. If reading isn’t your thing, strive to make that your challenge. Your academic journey, your personal well-being, and your professional endeavors will all benefit from your reading. Put forth the effort and make it your thing. The long-term benefits will far outweigh the sacrifices you make now.

7.1 The Nature and Types of Reading

Questions to consider:

- What are the pros and cons of online reading?

- How can distinguishing between reading types help you academically and personally?

- How can you best prepare to read for college?

Research supports the idea that reading is good for you. Students who read at or above reading level throughout elementary and secondary school have a higher chance of starting—and more importantly, finishing—college. Educational researchers convincingly claim that reading improves everything from grades to vocabulary (Cunningham 2).

If you don’t particularly enjoy reading, don’t despair. We read for a variety of reasons, and you may just have to step back and take a bigger picture of your reading habits to understand why you avoid engaging in this important skill. The myriad distractions we now face as well as the intense information overload we can suffer on a daily basis in all aspects of our lives can combine to make it difficult to slow down to read, an activity that demands at least a modicum of attention in a way that most television and music do not. You may need to adjust your schedule for more reading time, especially in college, because every class you take will expect you to read more pages than you probably have in the past.

Types of Reading

We may read small items purely for immediate information, such as notes, e-mails, or directions to an unfamiliar location. You can find all sorts of information online about how to fix a faucet or tie a secure knot. You won’t have to spend too much time reading these sorts of texts because you have a specific goal in mind for them, and once you have accomplished that goal, you do not need to prolong the reading experience. These encounters with texts may not be memorable or stunning, but they don’t need to be. When we consider why we read longer pieces—outside of reading for pleasure—we can usually categorize the reasons into about two categories: 1) reading to introduce ourselves to new content, and 2) reading to more fully comprehend familiar content.

Figure 7.2 A bookstore or library can be a great place to explore. Aside from books and resources you need, you may find something that interests you or helps with your course work.

Reading to Introduce New Content

Glenn felt uncomfortable talking with his new roommates because he realized very quickly that he didn’t know anything about their major—architecture. Of course he knew that it had something to do with buildings and construction sites, but the field was so different from his discipline of biology that he decided he needed to find out more so he could at least engage in friendly conversation with his roommates. Since he would likely not go into their field, he didn’t need to go into full research mode. When we read to introduce new content, we can start off small and increase to better and more sophisticated sources. Much of our further study and reading depends on the sources we originally read, our purpose for finding out about this new topic, and our interest level.

Chances are, you have done this sort of exploratory reading before. You may read reviews of a new restaurant or look at what people say about a movie you aren’t sure you want to spend the money to see at the theater. This reading helps you decide. In academic settings, much of what you read in your courses may be relatively new content to you. You may have heard the word volcano and have a general notion of what it means, but until you study geology and other sciences in depth, you may not have a full understanding of the environmental origins, ecological impacts, and societal and historic responses to volcanoes. These perspectives will come from reading and digesting various material. When you are working with new content, you may need to schedule more time for reading and comprehending the information because you may need to look up unfamiliar terminology and you may have to stop more frequently to make sure you are truly grasping what the material means. When you have few ways to connect new material to your own prior knowledge, you have to work more diligently to comprehend it.

Application

Try an experiment with a group of classmates. Without looking on the Internet, try to brainstorm a list of 10 topics about which all of you may be interested but for which you know very little or nothing at all. Try to make the topics somewhat obscure rather than ordinary—for example, the possibility of the non-planet Pluto being reclassified again as opposed to something like why we need to drink water.

After you have this random list, think of ways you could find information to read about these weird topics. Our short answer is always: Google. But think of other ways as well. How else could you read about these topics if you don’t know anything about them? You may well be in a similar circumstance in some of your college classes, so you should listen carefully to your classmates on this one. Think beyond pat answers such as “I’d go to the library,” and press for what that researcher would do once at the library. What types of articles or books would you try to find? One reason that you should not always ignore the idea of doing research at the physical library is because once you are there and looking for information, you have a vast number of other sources readily available to you in a highly organized location. You also can tap into the human resources represented by the research librarians who likely can redirect you if you cannot find appropriate sources.

Reading to Comprehend Familiar Content

Reading about unfamiliar content is one thing, but what if you do know something about a topic already? Do you really still need to keep reading about it? Probably. For example, what if during the brainstorming activity in the previous section, you secretly felt rather smug because you know about the demotion of the one-time planet Pluto and that there is currently quite the scientific debate going on about that whole de-planet-ation thing. Of course, you didn’t say anything during the study session, mostly to spare your classmates any embarrassment, but you are pretty familiar with Pluto-gate. So now what? Can you learn anything new?

Again—probably. When did Pluto’s qualifications to be considered a planet come into question? What are the qualifications for being considered a planet? Why? Who even gets to decide these things? Why was it called Pluto in the first place? On Amazon alone, you can find hundreds of books about the once-planet Pluto (not to be confused with the Disney dog also named Pluto). A Google search brings up over 34 million options for your reading pleasure. You’ll have plenty to read, even if you do know something or quite a bit about a topic, but you’ll approach reading about a familiar topic and an unfamiliar one differently.

With familiar content, you can do some initial skimming to determine what you already know in the book or article, and mark what may be new information or a different perspective. You may not have to give your full attention to the information you know, but you will spend more time on the new viewpoints so you can determine how this new data meshes with what you already know. Is this writer claiming a radical new definition for the topic or an entirely opposite way to consider the subject matter, connecting it to other topics or disciplines in ways you have never considered?

When college students encounter material in a discipline-specific context and have some familiarity with the topic, they sometimes can allow themselves to become a bit overconfident about their knowledge level. Just because a student may have read an article or two or may have seen a TV documentary on a subject such as the criminal mind, that does not make them an expert. What makes an expert is a person who thoroughly studies a subject, usually for years, and understands all the possible perspectives of a subject as well as the potential for misunderstanding due to personal biases and the availability of false information about the topic.

7.2 Effective Reading Strategies

Questions to consider:

- What methods can you incorporate into your routine to allow adequate time for reading?

- What are the benefits and approaches to active reading?

- Do your courses or major have specific reading requirements?

Allowing Adequate Time for Reading

You should determine the reading requirements and expectations for every class very early in the semester. You also need to understand why you are reading the particular text you are assigned. Do you need to read closely for minute details that determine cause and effect? Or is your instructor asking you to skim several sources so you become more familiar with the topic? Knowing this reasoning will help you decide your timing, what notes to take, and how best to undertake the reading assignment.

Figure 7.3 If you plan to make time for reading while you commute, remember that unexpected events like delays and cancellations could impact your concentration.

Depending on the makeup of your schedule, you may end up reading both primary sources—such as legal documents, historic letters, or diaries—as well as textbooks, articles, and secondary sources, such as summaries or argumentative essays that use primary sources to stake a claim. You may also need to read current journalistic texts to stay current in local or global affairs. A realistic approach to scheduling your time to allow you to read and review all the reading you have for the semester will help you accomplish what can sometimes seem like an overwhelming task.

When you allow adequate time in your hectic schedule for reading, you are investing in your own success. Reading isn’t a magic pill, but it may seem like it when you consider all the benefits people reap from this ordinary practice. Famous successful people throughout history have been voracious readers. In fact, former U.S. president Harry Truman once said, “Not all readers are leaders, but all leaders are readers.” Writer of the U.S. Declaration of Independence, inventor, and also former U.S. president Thomas Jefferson claimed “I cannot live without books” at a time when keeping and reading books was an expensive pastime. Knowing what it meant to be kept from the joys of reading, 19th-century abolitionist Frederick Douglass said, “Once you learn to read, you will be forever free.” And finally, George R. R. Martin, the prolific author of the wildly successful Game of Thrones empire, declared, “A reader lives a thousand lives before he dies . . . The man who never reads lives only one.”

You can make time for reading in a number of ways that include determining your usual reading pace and speed, scheduling active reading sessions, and practicing recursive reading strategies.

Determining Reading Speed and Pacing

To determine your reading speed, select a section of text—passages in a textbook or pages in a novel. Time yourself reading that material for exactly 5 minutes, and note how much reading you accomplished in those 5 minutes. Multiply the amount of reading you accomplished in 5 minutes by 12 to determine your average reading pace (5 times 12 equals the 60 minutes of an hour). Of course, your reading pace will be different and take longer if you are taking notes while you read, but this calculation of reading pace gives you a good way to estimate your reading speed that you can adapt to other forms of reading.

|

Example Reading Times |

|

|

|

|

Reader |

Pages Read in 5 Minutes |

Pages per Hour |

Approximate Hours to Read 500 Pages |

|

Marta |

4 |

48 |

10 hours, 30 minutes |

|

Jordi |

3 |

36 |

13 hours |

|

Estevan |

5 |

60 |

8 hours, 20 minutes |

So, for instance, if Marta was able to read 4 pages of a dense novel for her English class in 5 minutes, she should be able to read about 48 pages in one hour. Knowing this, Marta can accurately determine how much time she needs to devote to finishing the novel within a set amount of time, instead of just guessing. If the novel Marta is reading is 497 pages, then Marta would take the total page count (497) and divide that by her hourly reading rate (48 pages/hour) to determine that she needs about 10 to 11 hours overall. To finish the novel spread out over two weeks, Marta needs to read a little under an hour a day to accomplish this goal.

Calculating your reading rate in this manner does not take into account days where you’re too distracted and you have to reread passages or days when you just aren’t in the mood to read. And your reading rate will likely vary depending on how dense the content you’re reading is (e.g., a complex textbook vs. a comic book). Your pace may slow down somewhat if you are not very interested in what the text is about. What this method will help you do is be realistic about your reading time as opposed to waging a guess based on nothing and then becoming worried when you have far more reading to finish than the time available.

Scheduling Set Times for Active Reading

Active reading takes longer than reading through passages without stopping. You may not need to read your latest sci-fi series actively while you’re lounging on the beach, but many other reading situations demand more attention from you. Active reading is particularly important for college courses. You are a scholar actively engaging with the text by posing questions, seeking answers, and clarifying any confusing elements. Plan to spend at least twice as long to read actively than to read passages without taking notes or otherwise marking select elements of the text.

To determine the time you need for active reading, use the same calculations you use to determine your traditional reading speed and double it. Remember that you need to determine your reading pace for all the classes you have in a particular semester and multiply your speed by the number of classes you have that require different types of reading.

|

Example Active Reading Times |

|

|

|

|

|

Reader |

Pages Read in 5 Minutes |

Pages per Hour |

Approximate Hours to Read 500 Pages |

Approximate Hours to Actively Read 500 Pages |

|

Marta |

4 |

48 |

10 hours, 30 minutes |

21 hours |

|

Jordi |

3 |

36 |

13 hours |

26 hours |

|

Estevan |

5 |

60 |

8 hours, 20 minutes |

16 hours, 40 minutes |

Practicing Recursive Reading Strategies

One fact about reading for college courses that may become frustrating is that, in a way, it never ends. For all the reading you do, you end up doing even more rereading. It may be the same content, but you may be reading the passage more than once to detect the emphasis the writer places on one aspect of the topic or how frequently the writer dismisses a significant counterargument. This rereading is called recursive reading.

For most of what you read at the college level, you are trying to make sense of the text for a specific purpose—not just because the topic interests or entertains you. You need your full attention to decipher everything that’s going on in complex reading material—and you even need to be considering what the writer of the piece may not be including and why. This is why reading for comprehension is recursive.

Specifically, this boils down to seeing reading not as a formula but as a process that is far more circular than linear. You may read a selection from beginning to end, which is an excellent starting point, but for comprehension, you’ll need to go back and reread passages to determine meaning and make connections between the reading and the bigger learning environment that led you to the selection—that may be a single course or a program in your college, or it may be the larger discipline, such as all biologists or the community of scholars studying beach erosion.

People often say writing is rewriting. For college courses, reading is rereading.

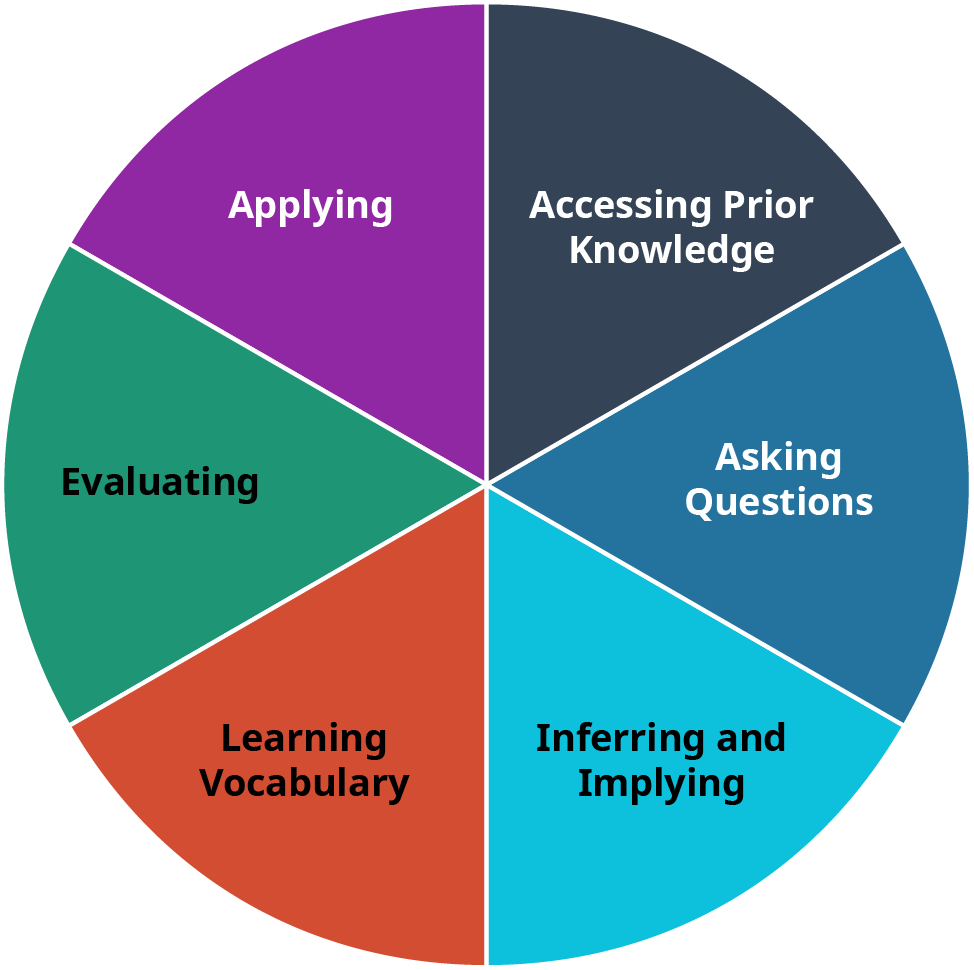

Strong readers engage in numerous steps, sometimes combining more than one step simultaneously, but knowing the steps nonetheless. They include, not always in this order:

- bringing any prior knowledge about the topic to the reading session,

- asking yourself pertinent questions, both orally and in writing, about the content you are reading,

- inferring and/or implying information from what you read,

- learning unfamiliar discipline-specific terms,

- evaluating what you are reading, and eventually,

- applying what you’re reading to other learning and life situations you encounter.

Let’s break these steps into manageable chunks, because you are actually doing quite a lot when you read.

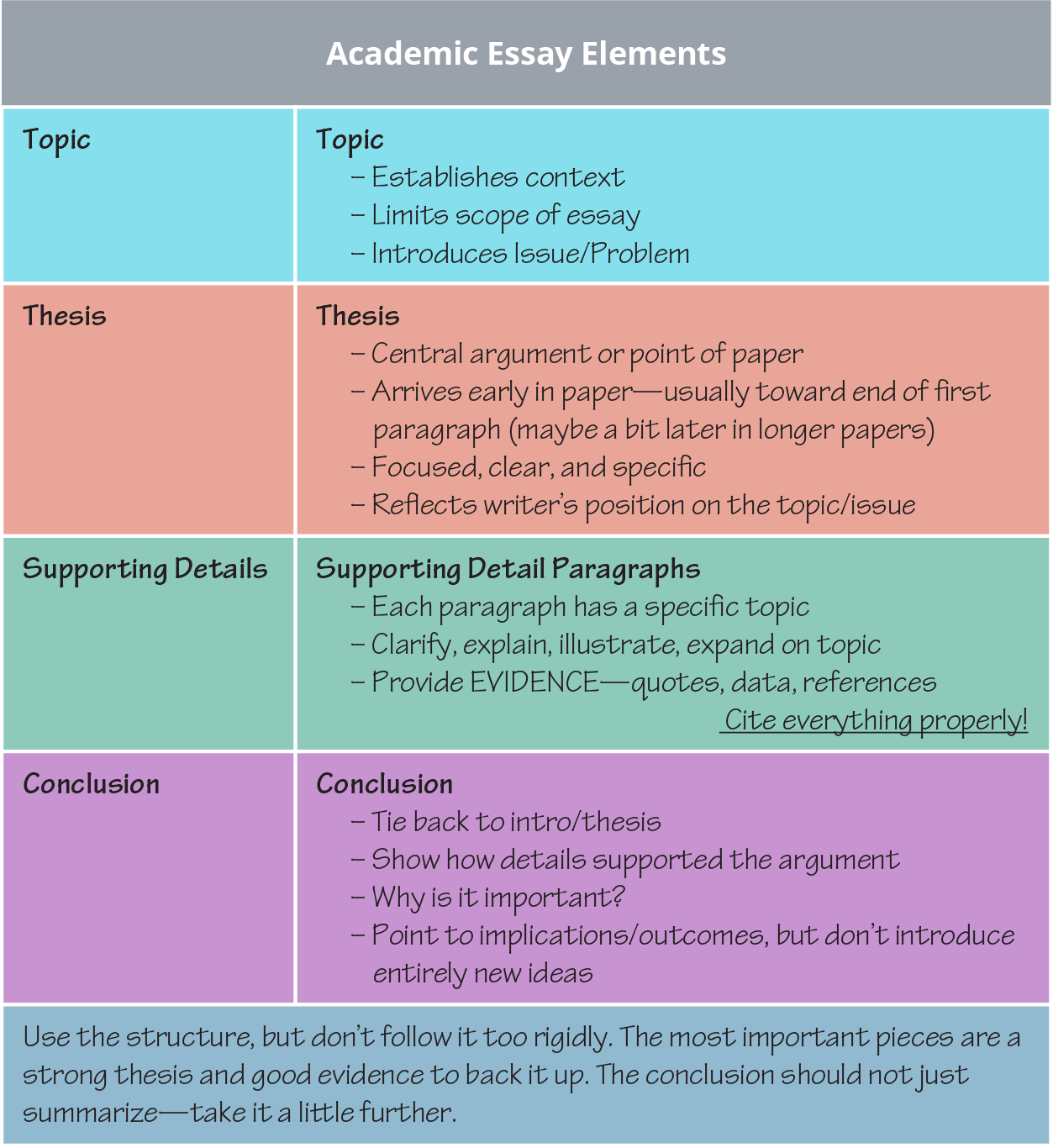

Figure 7.4 The six elements of recursive reading should be considered as a circular, not linear, process.

Accessing Prior Knowledge

When you read, you naturally think of anything else you may know about the topic, but when you read deliberately and actively, you make yourself more aware of accessing this prior knowledge. Have you ever watched a documentary about this topic? Did you study some aspect of it in another class? Do you have a hobby that is somehow connected to this material? All of this thinking will help you make sense of what you are reading.

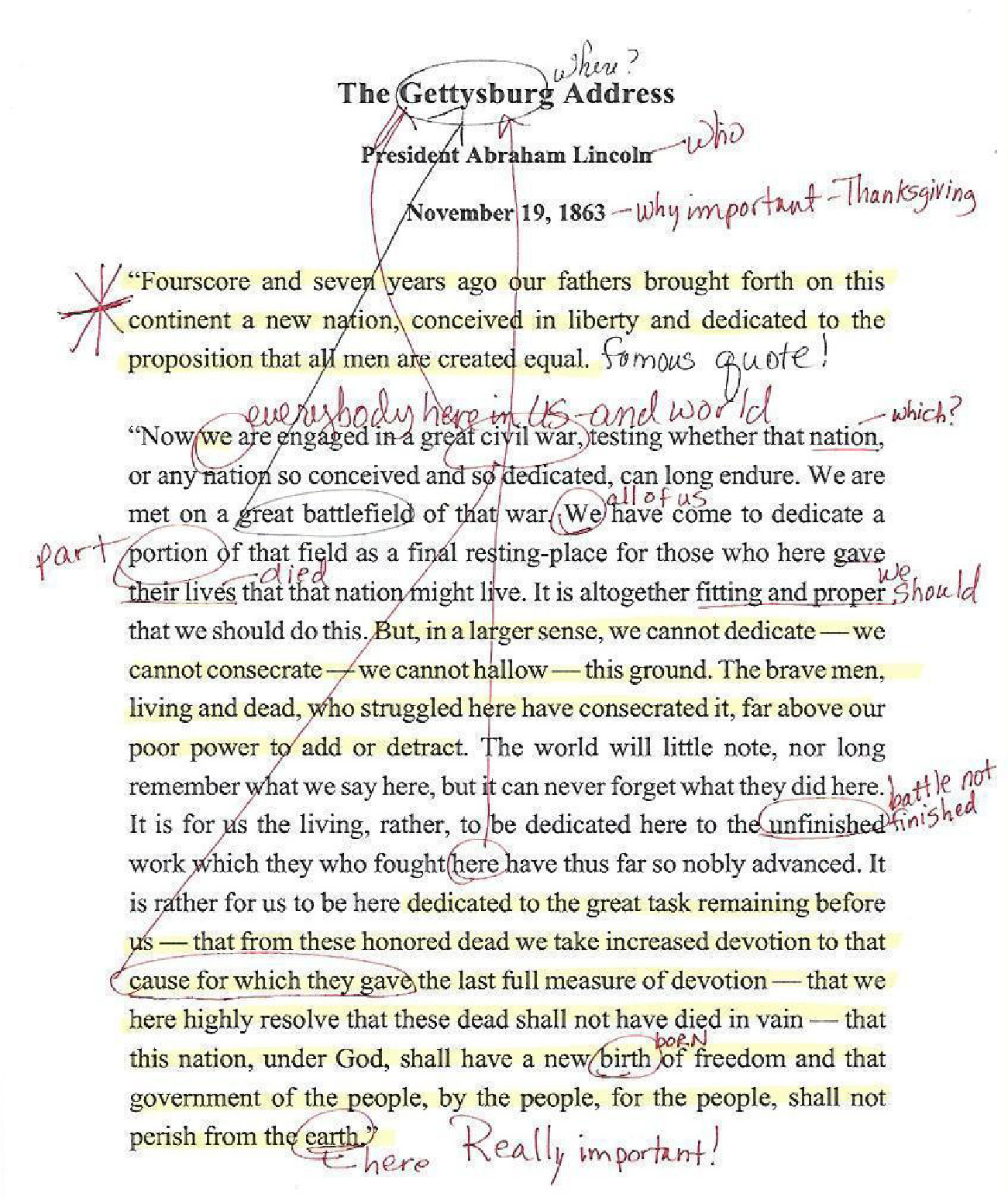

Application

Imagining that you were given a chapter to read in your American history class about the Gettysburg Address, write down what you already know about this historic document. How might thinking through this prior knowledge help you better understand the text?

Asking Questions

Humans are naturally curious beings. As you read actively, you should be asking questions about the topic you are reading. Don’t just say the questions in your mind; write them down. You may ask: Why is this topic important? What is the relevance of this topic currently? Was this topic important a long time ago but irrelevant now? Why did my professor assign this reading?

You need a place where you can actually write down these questions; a separate page in your notes is a good place to begin. If you are taking notes on your computer, start a new document and write down the questions. Leave some room to answer the questions when you begin and again after you read.

Inferring and Implying

When you read, you can take the information on the page and infer, or conclude responses to related challenges from evidence or from your own reasoning. A student will likely be able to infer what material the professor will include on an exam by taking good notes throughout the classes leading up to the test.

Writers may imply information without directly stating a fact for a variety of reasons. Sometimes a writer may not want to come out explicitly and state a bias, but may imply or hint at his or her preference for one political party or another. You have to read carefully to find implications because they are indirect, but watching for them will help you comprehend the whole meaning of a passage.

Learning Vocabulary

Vocabulary specific to certain disciplines helps practitioners in that field engage and communicate with each other. Few people beyond undertakers and archeologists likely use the term sarcophagus in everyday communications, but for those disciplines, it is a meaningful distinction. Looking at the example, you can use context clues to figure out the meaning of the term sarcophagus because it is something undertakers and/or archeologists would recognize. At the very least, you can guess that it has something to do with death. As a potential professional in the field you’re studying, you need to know the lingo. You may already have a system in place to learn discipline-specific vocabulary, so use what you know works for you. Two strong strategies are to look up words in a dictionary (online or hard copy) to ensure you have the exact meaning for your discipline and to keep a dedicated list of words you see often in your reading. You can list the words with a short definition so you have a quick reference guide to help you learn the vocabulary.

Evaluating

Intelligent people always question and evaluate. This doesn’t mean they don’t trust others; they just need verification of facts to understand a topic well. It doesn’t make sense to learn incomplete or incorrect information about a subject just because you didn’t take the time to evaluate all the sources at your disposal. When early explorers were afraid to sail the world for fear of falling off the edge, they weren’t stupid; they just didn’t have all the necessary data to evaluate the situation.

When you evaluate a text, you are seeking to understand the presented topic. Depending on how long the text is, you will perform a number of steps and repeat many of these steps to evaluate all the elements the author presents. When you evaluate a text, you need to do the following:

- Scan the title and all headings.

- Read through the entire passage fully.

- Question what main point the author is making.

- Decide who the audience is.

- Identify what evidence/support the author uses.

- Consider if the author presents a balanced perspective on the main point.

- Recognize if the author introduced any biases in the text.

When you go through a text looking for each of these elements, you need to go beyond just answering the surface question; for instance, the audience may be a specific field of scientists, but could anyone else understand the text with some explanation? Why would that be important?

Analysis Question

Think of an article you need to read for a class. Take the steps above on how to evaluate a text, and apply the steps to the article. When you accomplish the task in each step, ask yourself and take notes to answer the question: Why is this important? For example, when you read the title, does that give you any additional information that will help you comprehend the text? If the text were written for a different audience, what might the author need to change to accommodate that group? How does an author’s bias distort an argument? This deep evaluation allows you to fully understand the main ideas and place the text in context with other material on the same subject, with current events, and within the discipline.

Applying

When you learn something new, it always connects to other knowledge you already have. One challenge we have is applying new information. It may be interesting to know the distance to the moon, but how do we apply it to something we need to do? If your biology instructor asked you to list several challenges of colonizing Mars and you do not know much about that planet’s exploration, you may be able to use your knowledge of how far Earth is from the moon to apply it to the new task. You may have to read several other texts in addition to reading graphs and charts to find this information.

That was the challenge the early space explorers faced along with myriad unknowns before space travel was a more regular occurrence. They had to take what they already knew and could study and read about and apply it to an unknown situation. These explorers wrote down their challenges, failures, and successes, and now scientists read those texts as a part of the ever-growing body of text about space travel. Application is a sophisticated level of thinking that helps turn theory into practice and challenges into successes.

Preparing to Read for Specific Disciplines in College

Different disciplines in college may have specific expectations, but you can depend on all subjects asking you to read to some degree. In this college reading requirement, you can succeed by learning to read actively, researching the topic and author, and recognizing how your own preconceived notions affect your reading. Reading for college isn’t the same as reading for pleasure or even just reading to learn something on your own because you are casually interested.

In college courses, your instructor may ask you to read articles, chapters, books, or primary sources (those original documents about which we write and study, such as letters between historic figures or the Declaration of Independence). Your instructor may want you to have a general background on a topic before you dive into that subject in class, so that you know the history of a topic, can start thinking about it, and can engage in a class discussion with more than a passing knowledge of the issue.

If you are about to participate in an in-depth six-week consideration of the U.S. Constitution but have never read it or anything written about it, you will have a hard time looking at anything in detail or understanding how and why it is significant. As you can imagine, a great deal has been written about the Constitution by scholars and citizens since the late 1700s when it was first put to paper (that’s how they did it then). While the actual document isn’t that long (about 12–15 pages depending on how it is presented), learning the details on how it came about, who was involved, and why it was and still is a significant document would take a considerable amount of time to read and digest. So, how do you do it all? Especially when you may have an instructor who drops hints that you may also love to read a historic novel covering the same time period . . . in your spare time, not required, of course! It can be daunting, especially if you are taking more than one course that has time-consuming reading lists. With a few strategic techniques, you can manage it all, but know that you must have a plan and schedule your required reading so you are also able to pick up that recommended historic novel—it may give you an entirely new perspective on the issue.

Strategies for Reading in College Disciplines

No universal law exists for how much reading instructors and institutions expect college students to undertake for various disciplines. Suffice it to say, it’s a LOT.

For most students, it is the volume of reading that catches them most off guard when they begin their college careers. A full course load might require 10–15 hours of reading per week, some of that covering content that will be more difficult than the reading for other courses.

You cannot possibly read word-for-word every single document you need to read for all your classes. That doesn’t mean you give up or decide to only read for your favorite classes or concoct a scheme to read 17 percent for each class and see how that works for you. You need to learn to skim, annotate, and take notes. All of these techniques will help you comprehend more of what you read, which is why we read in the first place. We’ll talk more later about annotating and notetaking, but for now consider what you know about skimming as opposed to active reading.

Skimming

Skimming is not just glancing over the words on a page (or screen) to see if any of it sticks. Effective skimming allows you to take in the major points of a passage without the need for a time-consuming reading session that involves your active use of notations and annotations. Often you will need to engage in that painstaking level of active reading, but skimming is the first step—not an alternative to deep reading. The fact remains that neither do you need to read everything nor could you possibly accomplish that given your limited time. So learn this valuable skill of skimming as an accompaniment to your overall study tool kit, and with practice and experience, you will fully understand how valuable it is.

When you skim, look for guides to your understanding: headings, definitions, pull quotes, tables, and context clues. Textbooks are often helpful for skimming—they may already have made some of these skimming guides in bold or a different color, and chapters often follow a predictable outline. Some even provide an overview and summary for sections or chapters. Use whatever you can get, but don’t stop there. In textbooks that have some reading guides, or especially in text that does not, look for introductory words such as First or The purpose of this article . . . or summary words such as In conclusion . . . or Finally. These guides will help you read only those sentences or paragraphs that will give you the overall meaning or gist of a passage or book.

Now move to the meat of the passage. You want to take in the reading as a whole. For a book, look at the titles of each chapter if available. Read each chapter’s introductory paragraph and determine why the writer chose this particular order. Depending on what you’re reading, the chapters may be only informational, but often you’re looking for a specific argument. What position is the writer claiming? What support, counterarguments, and conclusions is the writer presenting?

Don’t think of skimming as a way to buzz through a boring reading assignment. It is a skill you should master so you can engage, at various levels, with all the reading you need to accomplish in college. End your skimming session with a few notes—terms to look up, questions you still have, and an overall summary. And recognize that you likely will return to that book or article for a more thorough reading if the material is useful.

Active Reading Strategies

Active reading differs significantly from skimming or reading for pleasure. You can think of active reading as a sort of conversation between you and the text (maybe between you and the author, but you don’t want to get the author’s personality too involved in this metaphor because that may skew your engagement with the text).

When you sit down to determine what your different classes expect you to read and you create a reading schedule to ensure you complete all the reading, think about when you should read the material strategically, not just how to get it all done. You should read textbook chapters and other reading assignments before you go into a lecture about that information. Don’t wait to see how the lecture goes before you read the material, or you may not understand the information in the lecture. Reading before class helps you put ideas together between your reading and the information you hear and discuss in class.

Different disciplines naturally have different types of texts, and you need to take this into account when you schedule your time for reading class material. For example, you may look at a poem for your world literature class and assume that it will not take you long to read because it is relatively short compared to the dense textbook you have for your economics class. But reading and understanding a poem can take a considerable amount of time when you realize you may need to stop numerous times to review the separate word meanings and how the words form images and connections throughout the poem.

The SQ3R Reading Strategy

You may have heard of the SQ3R method for active reading in your early education. This valuable technique is perfect for college reading. The title stands for Survey, Question, Read, Recite, Review, and you can use the steps on virtually any assigned passage. Designed by Francis Pleasant Robinson in his 1961 book Effective Study, the active reading strategy gives readers a systematic way to work through any reading material.

Survey is similar to skimming. You look for clues to meaning by reading the titles, headings, introductions, summary, captions for graphics, and keywords. You can survey almost anything connected to the reading selection, including the copyright information, the date of the journal article, or the names and qualifications of the author(s). In this step, you decide what the general meaning is for the reading selection.

Question is your creation of questions to seek the main ideas, support, examples, and conclusions of the reading selection. Ask yourself these questions separately. Try to create valid questions about what you are about to read that have come into your mind as you engaged in the Survey step. Try turning the headings of the sections in the chapter into questions. Next, how does what you’re reading relate to you, your school, your community, and the world?

Read is when you actually read the passage. Try to find the answers to questions you developed in the previous step. Decide how much you are reading in chunks, either by paragraph for more complex readings or by section or even by an entire chapter. When you finish reading the selection, stop to make notes. Answer the questions by writing a note in the margin or other white space of the text.

You may also carefully underline or highlight text in addition to your notes. Use caution here that you don’t try to rush this step by haphazardly circling terms or the other extreme of underlining huge chunks of text. Don’t over-mark. You aren’t likely to remember what these cryptic marks mean later when you come back to use this active reading session to study. The text is the source of information—your marks and notes are just a way to organize and make sense of that information.

Recite means to speak out loud. By reciting, you are engaging other senses to remember the material—you read it (visual) and you said it (auditory). Stop reading momentarily in the step to answer your questions or clarify confusing sentences or paragraphs. You can recite a summary of what the text means to you. If you are not in a place where you can verbalize, such as a library or classroom, you can accomplish this step adequately by saying it in your head; however, to get the biggest bang for your buck, try to find a place where you can speak aloud. You may even want to try explaining the content to a friend.

Review is a recap. Go back over what you read and add more notes, ensuring you have captured the main points of the passage, identified the supporting evidence and examples, and understood the overall meaning. You may need to repeat some or all of the SQR3 steps during your review depending on the length and complexity of the material. Before you end your active reading session, write a short (no more than one page is optimal) summary of the text you read.

Reading Primary and Secondary Sources

Primary sources are original documents we study and from which we glean information; primary sources include letters, first editions of books, legal documents, and a variety of other texts. When scholars look at these documents to understand a period in history or a scientific challenge and then write about their findings, the scholar’s article is considered a secondary source. Readers have to keep several factors in mind when reading both primary and secondary sources.

Primary sources may contain dated material we now know is inaccurate. It may contain personal beliefs and biases the original writer didn’t intent to be openly published, and it may even present fanciful or creative ideas that do not support current knowledge. Readers can still gain great insight from primary sources, but readers need to understand the context from which the writer of the primary source wrote the text.

Likewise, secondary sources are inevitably another person’s perspective on the primary source, so a reader of secondary sources must also be aware of potential biases or preferences the secondary source writer inserts in the writing that may persuade an incautious reader to interpret the primary source in a particular manner.

For example, if you were to read a secondary source that is examining the U.S. Declaration of Independence (the primary source), you would have a much clearer idea of how the secondary source scholar presented the information from the primary source if you also read the Declaration for yourself instead of trusting the other writer’s interpretation. Most scholars are honest in writing secondary sources, but you as a reader of the source are trusting the writer to present a balanced perspective of the primary source. When possible, you should attempt to read a primary source in conjunction with the secondary source. The Internet helps immensely with this practice.

What Students Say

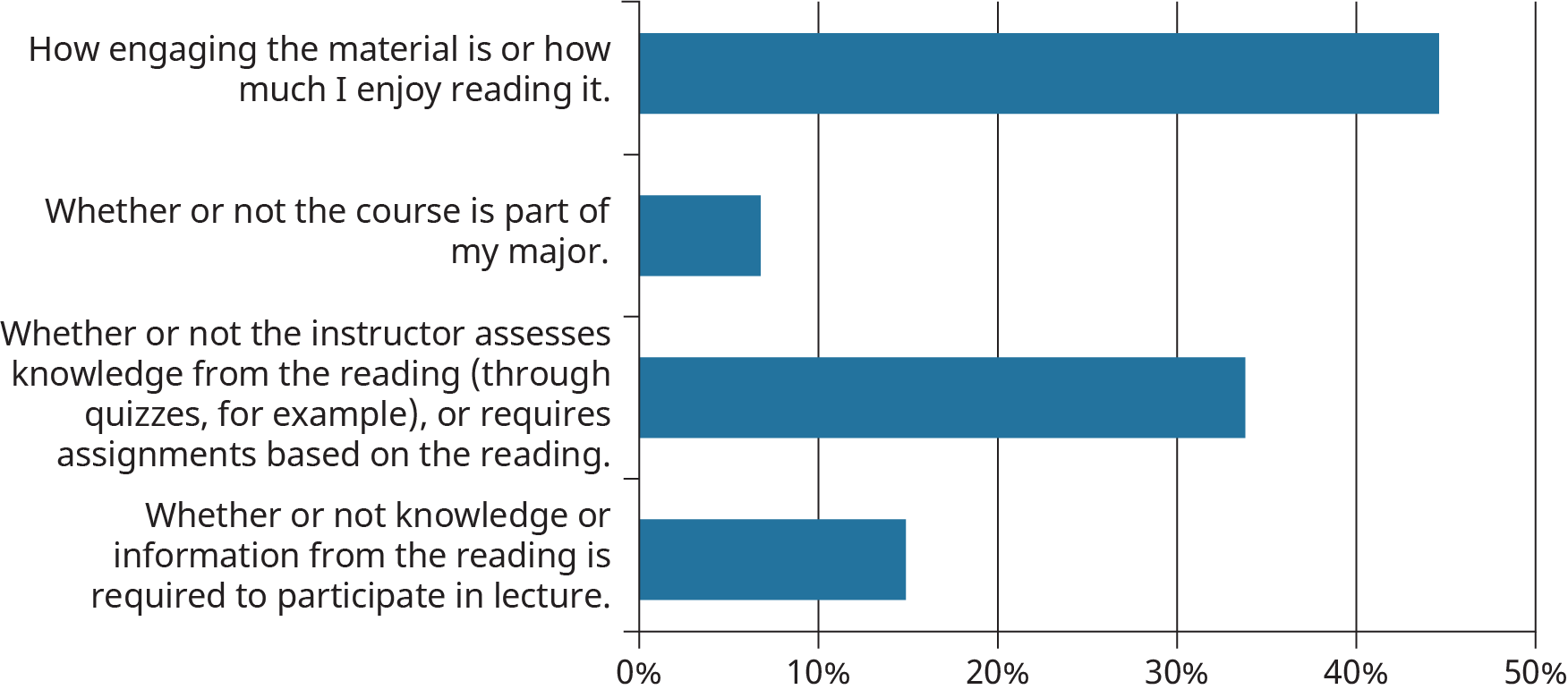

- What is the most influential factor in how thoroughly you read the material for a given course?

- How engaging the material is or how much I enjoy reading it.

- Whether or not the course is part of my major.

- Whether or not the instructor assesses knowledge from the reading (through quizzes, for example), or requires assignments based on the reading.

- Whether or not knowledge or information from the reading is required to participate in lecture.

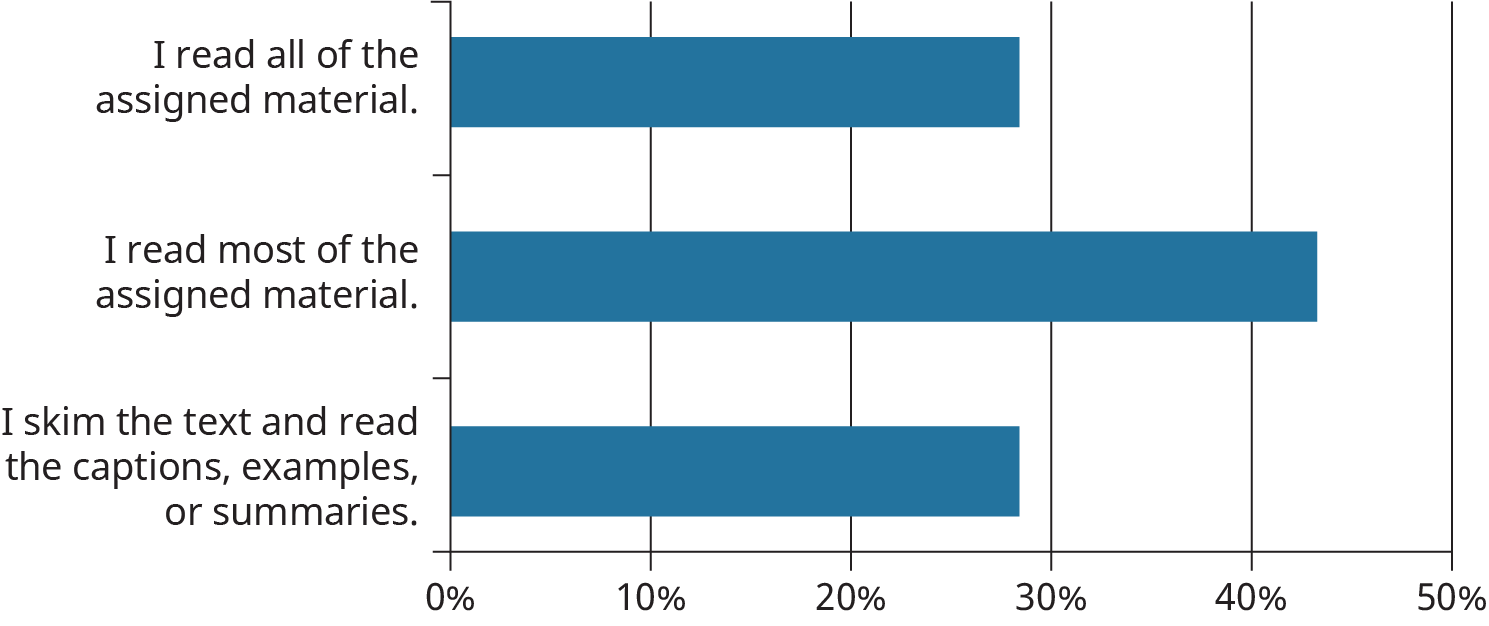

- What best describes your reading approach for required texts/materials for your classes?

- I read all of the assigned material.

- I read most of the assigned material.

- I skim the text and read the captions, examples, or summaries.

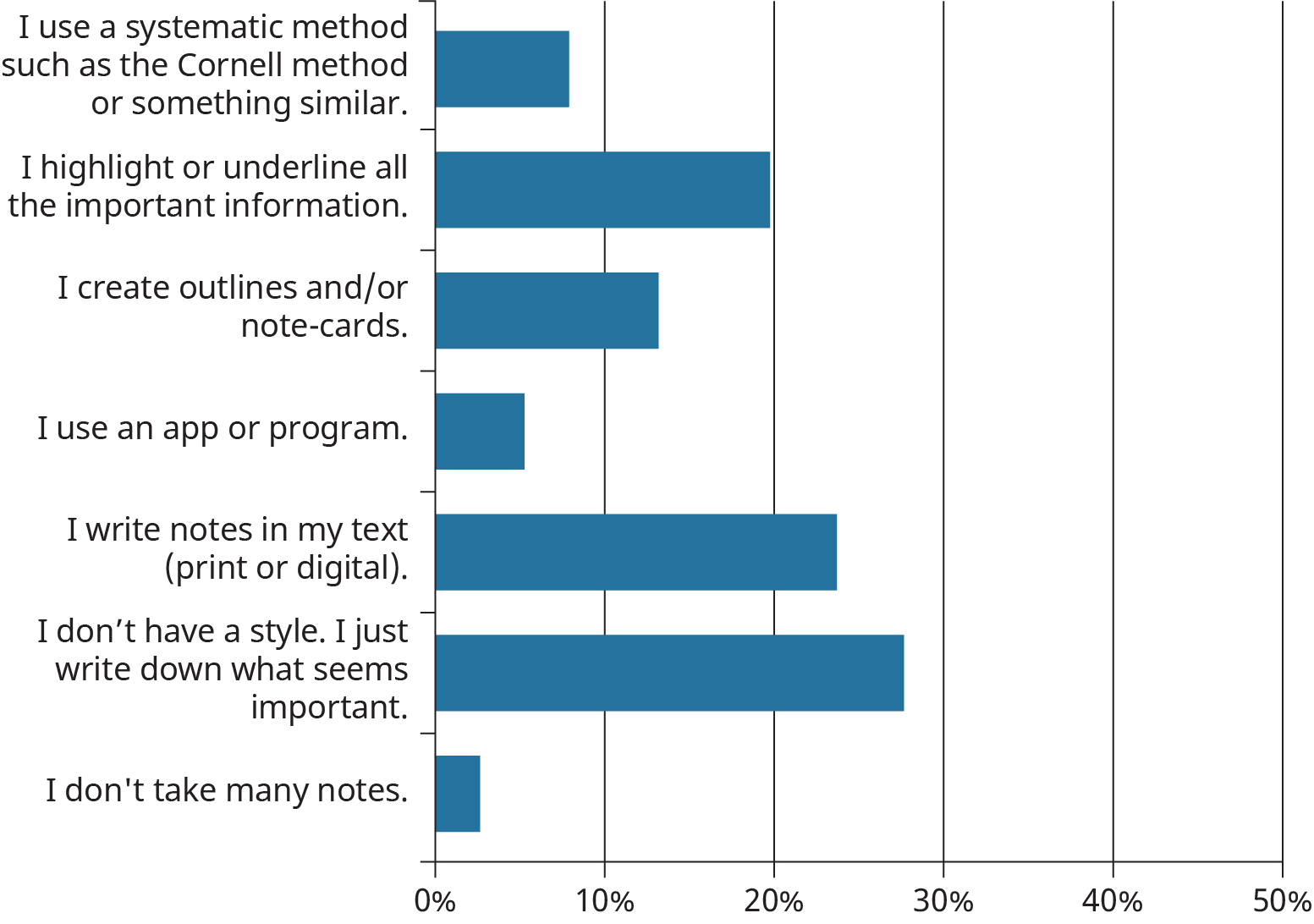

- What best describes your notetaking style?

- I use a systematic method such as the Cornell method or something similar.

- I highlight or underline all the important information.

- I create outlines and/or note-cards.

- I use an app or program.

- I write notes in my text (print or digital).

- I don’t have a style. I just write down what seems important.

- I don’t take many notes.

Students offered their views on these questions, and the results are displayed in the graphs below.

What is the most influential factor in how thoroughly you read the material for a given course?

Figure 7.5

What best describes your reading approach for required texts/materials for your classes?

Figure 7.6

What best describes your notetaking style?

Figure 7.7

Researching Topic and Author

During your preview stage, sometimes called pre-reading, you can easily pick up on information from various sources that may help you understand the material you’re reading more fully or place it in context with other important works in the discipline. If your selection is a book, flip it over or turn to the back pages and look for an author’s biography or note from the author. See if the book itself contains any other information about the author or the subject matter.

The main things you need to recall from your reading in college are the topics covered and how the information fits into the discipline. You can find these parts throughout the textbook chapter in the form of headings in larger and bold font, summary lists, and important quotations pulled out of the narrative. Use these features as you read to help you determine what the most important ideas are.

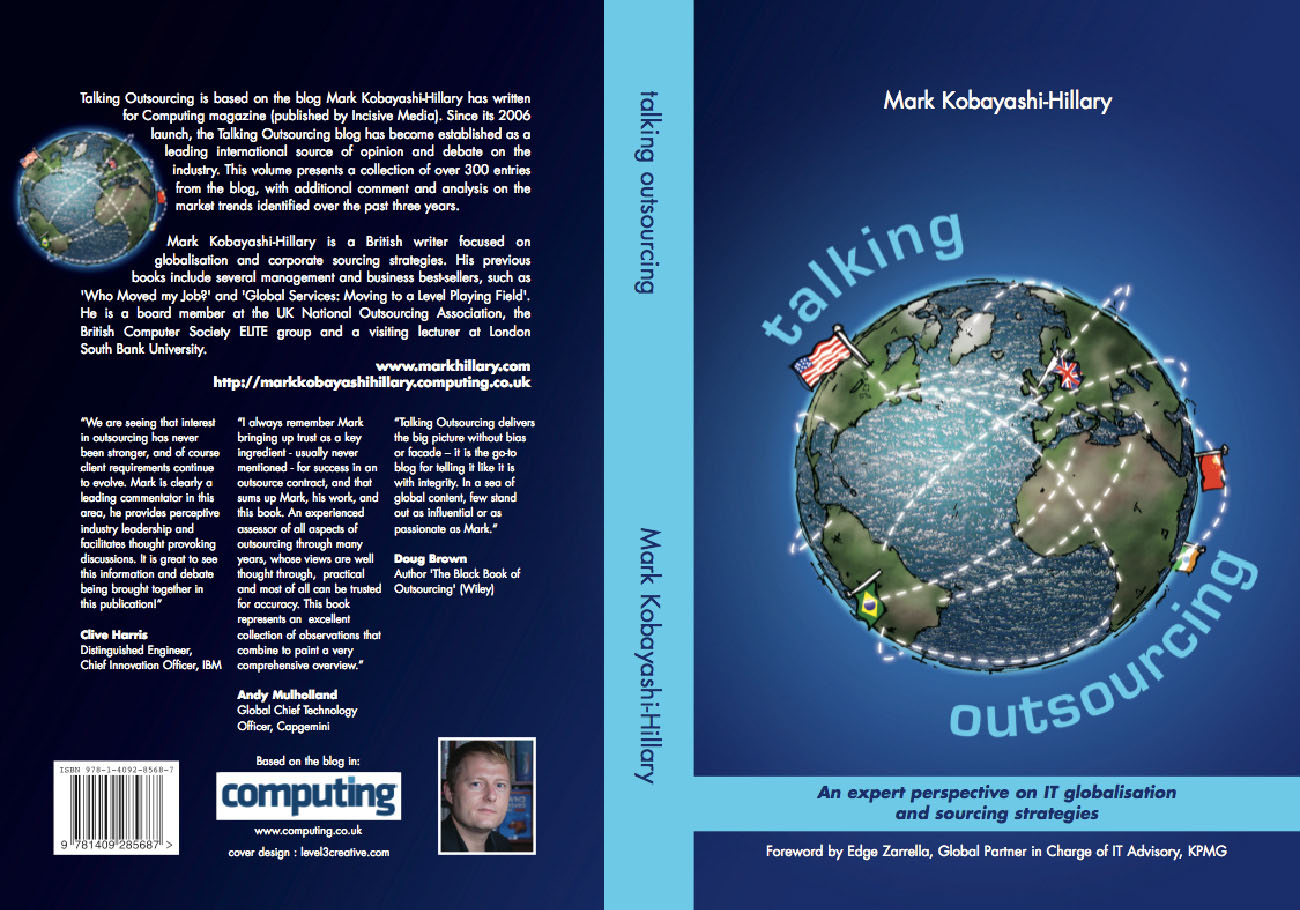

Figure 7.8 Learning about the book you’re reading can provide good context and information. Look for an author’s biography and forward on the back cover or in the first few pages. (Credit: Mark Hillary / Flickr / Attribution 2.0 Generic (CC-BY 2.0))

Remember, many books use quotations about the book or author as testimonials in a marketing approach to sell more books, so these may not be the most reliable sources of unbiased opinions, but it’s a start. Sometimes you can find a list of other books the author has written near the front of a book. Do you recognize any of the other titles? Can you do an Internet search for the name of the book or author? Go beyond the search results that want you to buy the book and see if you can glean any other relevant information about the author or the reading selection. Beyond a standard Internet search, try the library article database. These are more relevant to academic disciplines and contain resources you typically will not find in a standard search engine. If you are unfamiliar with how to use the library database, ask a reference librarian on campus. They are often underused resources that can point you in the right direction.

Understanding Your Own Preset Ideas on a Topic

Laura really enjoys learning about environmental issues. She has read many books and watched numerous televised documentaries on this topic and actively seeks out additional information on the environment. While Laura’s interest can help her understand a new reading encounter about the environment, Laura also has to be aware that with this interest, she also brings forward her preset ideas and biases about the topic. Sometimes these prejudices against other ideas relate to religion or nationality or even just tradition. Without evidence, thinking the way we always have is not a good enough reason; evidence can change, and at the very least it needs honest review and assessment to determine its validity. Ironically, we may not want to learn new ideas because that may mean we would have to give up old ideas we have already mastered, which can be a daunting prospect.

With every reading situation about the environment, Laura needs to remain open-minded about what she is about to read and pay careful attention if she begins to ignore certain parts of the text because of her preconceived notions. Learning new information can be very difficult if you balk at ideas that are different from what you’ve always thought. You may have to force yourself to listen to a different viewpoint multiple times to make sure you are not closing your mind to a viable solution your mindset does not currently allow.

Analysis Question

Can you think of times you have struggled reading college content for a course? Which of these strategies might have helped you understand the content? Why do you think those strategies would work?

7.3 Taking Notes

Questions to consider:

- How can you prepare to take notes to maximize the effectiveness of the experience?

- What are some specific strategies you can employ for better notetaking?

- Why is annotating your notes after the notetaking session a critical step to follow?

Beyond providing a record of the information you are reading or hearing, notes help you organize the ideas and help you make meaning out of something about which you may not be familiar, so notetaking and reading are two compatible skill sets. Taking notes also helps you stay focused on the question at hand. Nanami often takes notes during presentations or class lectures so she can follow the speaker’s main points and condense the material into a more readily usable format. Strong notes build on your prior knowledge of a subject, help you discuss trends or patterns present in the information, and direct you toward areas needing further research or reading.

Figure 7.9 Strong notes build on your prior knowledge of a subject, help you discuss trends or patterns present in the information, and direct you toward areas needing further research or reading.

It is not a good habit to transcribe every single word a speaker utters—even if you have an amazing ability to do that. Most of us don’t have that court-reporter-esque skill level anyway, and if we try, we would end up missing valuable information. Learn to listen for main ideas and distinguish between these main ideas and details that typically support the ideas. Include examples that explain the main ideas, but do so using understandable abbreviations.

Think of all notes as potential study guides. In fact, if you only take notes without actively working on them after the initial notetaking session, the likelihood of the notes helping you is slim. Research on this topic concludes that without active engagement after taking notes, most students forget 60–75 percent of material over which they took the notes—within two days! That sort of defeats the purpose, don’t you think? This information about memory loss was first brought to light by 19th-century German psychologist Hermann Ebbinghaus. Fortunately, you do have the power to thwart what is sometimes called the Ebbinghaus Forgetting Curve by reinforcing what you learned through review at intervals shortly after you take in the material and frequently thereafter.

If you are a musician, you’ll understand this phenomenon well. When you first attempt a difficult piece of music, you may not remember the chords and notes well at all, but after frequent practice and review, you generate a certain muscle memory and cognitive recall that allows you to play the music more easily.

Notetaking may not be the most glamorous aspect of your higher-education journey, but it is a study practice you will carry throughout college and into your professional life. Setting yourself up for successful notetaking is almost as important as the actual taking of notes, and what you do after your notetaking session is equally significant. Well-written notes help you organize your thoughts, enhance your memory, and participate in class discussion, and they prepare you to respond successfully on exams. With all that riding on your notes, it would behoove you to learn how to take notes properly and continue to improve your notetaking skills.

Analysis Question

Do you currently have a preferred way to take notes? When did you start using it? Has it been effective? What other strategy might work for you?

Preparing to Take Notes

Preparing to take notes means more than just getting out your laptop or making sure you bring pen and paper to class. You’ll do a much better job with your notes if you understand why we take notes, have a strong grasp on your preferred notetaking system, determine your specific priorities depending on your situation, and engage in some version of efficient shorthand.

Like handwriting and fingerprints, we all have unique and fiercely independent notetaking habits. These understandably and reasonably vary from one situation to the next, but you can only improve your skills by learning more about ways to take effective notes and trying different methods to find a good fit.

The very best notes are the ones you take in an organized manner that encourages frequent review and use as you progress through a topic or course of study. For this reason, you need to develop a way to organize all your notes for each class so they remain together and organized. As old-fashioned as it sounds, a clunky three-ring binder is an excellent organizational container for class notes. You can easily add to previous notes, insert handouts you may receive in class, and maintain a running collection of materials for each separate course. If the idea of carrying around a heavy binder has you rolling your eyes, then transfer that same structure into your computer files. If you don’t organize your many documents into some semblance of order on your computer, you will waste significant time searching for improperly named or saved files.

You may be interested in relatively new research on what is the more effective notetaking strategy: handwriting versus typing directly into a computer. While individuals have strong personal opinions on this subject, most researchers agree that the format of student notes is less important than what students do with the notes they take afterwards. Both handwriting notes and using a computer for notetaking have pros and cons.

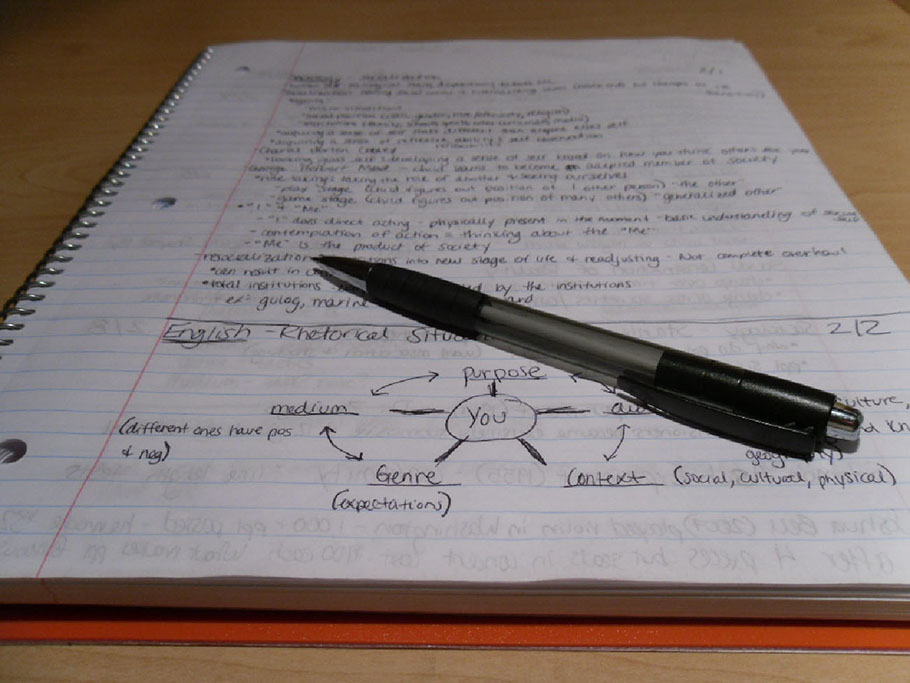

Figure 7.10 The best notes are the ones you take in an organized manner. Frequent review and further annotation are important to build a deep and useful understanding of the material. (Credit: English106 / Flickr / Attribution 2.0 Generic (CC-BY 2.0))

Managing Notetaking Systems (Computer, Paper/Pen, Note Cards, Textbook)

Whichever of the many notetaking systems you choose (and new ones seem to come out almost daily), the very best one is the one that you will use consistently. The skill and art of notetaking is not automatic for anyone; it takes a great deal of practice, patience, and continuous attention to detail. Add to that the fact that you may need to master multiple notetaking techniques for different classes, and you have some work to do. Unless you are specifically directed by your instructor, you are free to combine the best parts of different systems if you are most comfortable with that hybrid system.

Just to keep yourself organized, all your notes should start off with an identifier, including at the very least the date, the course name, the topic of the lecture/presentation, and any other information you think will help you when you return to use the notes for further study, test preparation, or assignment completion. Additional, optional information may be the number of notetaking sessions about this topic or reminders to cross-reference class handouts, textbook pages, or other course materials. It’s also always a good idea to leave some blank space in your notes so you can insert additions and questions you may have as you review the material later.

Notetaking Strategies

You may have a standard way you take all your notes for all your classes. When you were in high school, this one-size-fits-all approach may have worked. Now that you’re in college, reading and studying more advanced topics, your general method may still work some of the time, but you should have some different strategies in place if you find that your method isn’t working as well with college content. You probably will need to adopt different notetaking strategies for different subjects. The strategies in this section represent various ways to take notes in such a way that you are able to study after the initial notetaking session.

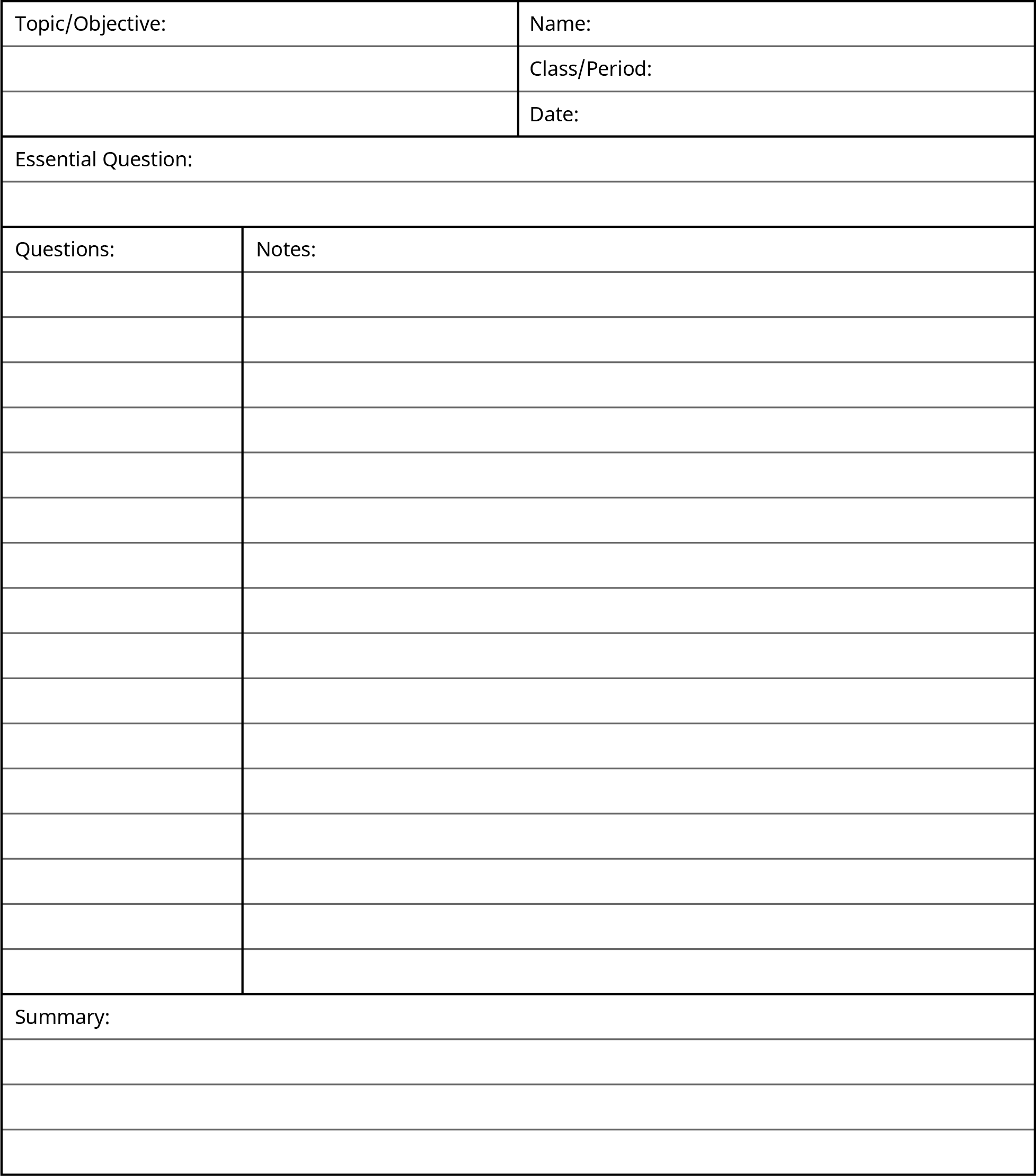

Cornell Method

One of the most recognizable notetaking systems is called the Cornell Method, a relatively simple way to take effective notes devised by Cornell University education professor Dr. Walter Pauk in the 1940s. In this system, you take a standard piece of note paper and divide it into three sections by drawing a horizontal line across your paper about one to two inches from the bottom of the page (the summary area) and then drawing a vertical line to separate the rest of the page above this bottom area, making the left side about two inches (the recall column) and leaving the biggest area to the right of your vertical line (the notes column). You may want to make one page and then copy as many pages as you think you’ll need for any particular class, but one advantage of this system is that you can generate the sections quickly. Because you have divided up your page, you may end up using more paper than you would if you were writing on the entire page, but the point is not to keep your notes to as few pages as possible. The Cornell Method provides you with a well-organized set of notes that will help you study and review your notes as you move through the course. If you are taking notes on your computer, you can still use the Cornell Method in Word or Excel on your own or by using a template someone else created.

Figure 7.11 The Cornell Method provides a straightforward, organized, and flexible approach

Now that you have the notetaking format generated, the beauty of the Cornell Method is its organized simplicity. Just write on one side of the page (the right-hand notes column)—this will help later when you are reviewing and revising your notes. During your notetaking session, use the notes column to record information over the main points and concepts of the lecture; try to put the ideas into your own words, which will help you not transcribe the speaker’s words verbatim. Skip lines between each idea in this column. Practice the shortcut abbreviations covered in the next section and avoid writing in complete sentences. Don’t make your notes too cryptic, but you can use bullet points or phrases equally well to convey meaning—we do it all the time in conversation. If you know you will need to expand the notes you are taking in class but don’t have time, you can put reminders directly in the notes by adding and underlining the word expand by the ideas you need to develop more fully.

As soon as possible after your notetaking session, preferably within eight hours but no more than twenty-four hours, read over your notes column and fill in any details you missed in class, including the places where you indicated you wanted to expand your notes. Then in the recall column, write any key ideas from the corresponding notes column—you can’t stuff this smaller recall column as if you’re explaining or defining key ideas. Just add the one- or two-word main ideas; these words in the recall column serve as cues to help you remember the detailed information you recorded in the notes column.

Once you are satisfied with your notes and recall columns, summarize this page of notes in two or three sentences using the summary area at the bottom of the sheet. This is an excellent time to get with another classmate or a group of students who all heard the same lecture to make sure you all understood the key points. Now, before you move onto something else, cover the large notes column, and quiz yourself over the key ideas you recorded in the recall column. Repeat this step often as you go along, not just immediately before an exam, and you will help your memory make the connections between your notes, your textbook reading, your in-class work, and assignments that you need to succeed on any quizzes and exams.

Figure 7.12 This sample set of notes in the Cornell Method is designed to make sense of a large amount of information. The process of organizing the notes can help you retain the information more effectively than less consistent methods.

The main advantage of the Cornell Method is that you are setting yourself up to have organized, workable notes. The neat format helps you move into study-mode without needing to re-copy less organized notes or making sense of a large mass of information you aren’t sure how to process because you can’t remember key ideas or what you meant. If you write notes in your classes without any sort of system and later come across something like “Napoleon—short” in the middle of a glob of notes, what can you do at this point? Is that important? Did it connect with something relevant from the lecture? How would you possibly know? You are your best advocate for setting yourself up for success in college.

Outlining

Other note organizing systems may help you in different disciplines. You can take notes in a formal outline if you prefer, using Roman numerals for each new topic, moving down a line to capital letters indented a few spaces to the right for concepts related to the previous topic, then adding details to support the concepts indented a few more spaces over and denoted by an Arabic numeral. You can continue to add to a formal outline by following these rules.

You don’t absolutely have to use the formal numerals and letter, but you have to then be careful to indent so you can tell when you move from a higher level topic to the related concepts and then to the supporting information. The main benefit of an outline is how organized it is. You have to be on your toes when you are taking notes in class to ensure you keep up the organizational format of the outline, which can be tricky if the lecture or presentation is moving quickly or covering many diverse topics.

The following formal outline example shows the basic pattern:

- Dogs (main topic–usually general)

- German Shepherd (concept related to main topic)

- Protection (supporting info about the concept)

- Assertive

- Loyal

- Weimaraner (concept related to main topic)

- Family-friendly (supporting info about the concept)

- Active

- Healthy

- German Shepherd (concept related to main topic)

- Cats (main topic)

- Siamese

You would just continue on with this sort of numbering and indenting format to show the connections between main ideas, concepts, and supporting details. Whatever details you do not capture in your notetaking session, you can add after the lecture as you review your outline.

Chart or table

Similar to creating an outline, you can develop a chart to compare and contrast main ideas in a notetaking session. Divide your paper into four or five columns with headings that include either the main topics covered in the lecture or categories such as How?, What?, When used?, Advantages/Pros, Disadvantages/Cons, or other divisions of the information. You write your notes into the appropriate columns as that information comes to light in the presentation.

|

Example of a Chart to Organize Ideas and Categories |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Structure |

Types |

Functions in Body |

Additional Notes |

|

Carbohydrates |

|

|

|

|

|

Lipids |

|

|

|

|

|

Proteins |

|

|

|

|

|

Nucleic Acid |

|

|

|

|

This format helps you pull out the salient ideas and establishes an organized set of notes to study later. (If you haven’t noticed that this reviewing later idea is a constant across all notetaking systems, you should…take note of that.) Notes by themselves that you never reference again are little more than scribblings. That would be a bit like compiling an extensive grocery list so you stay on budget when you shop, work all week on it, and then just throw it away before you get to the store. You may be able to recall a few items, but likely won’t be as efficient as you could be if you had the notes to reference. Just as you cannot read all the many books, articles, and documents you need to peruse for your college classes, you cannot remember the most important ideas of all the notes you will take as part of your courses, so you must review.

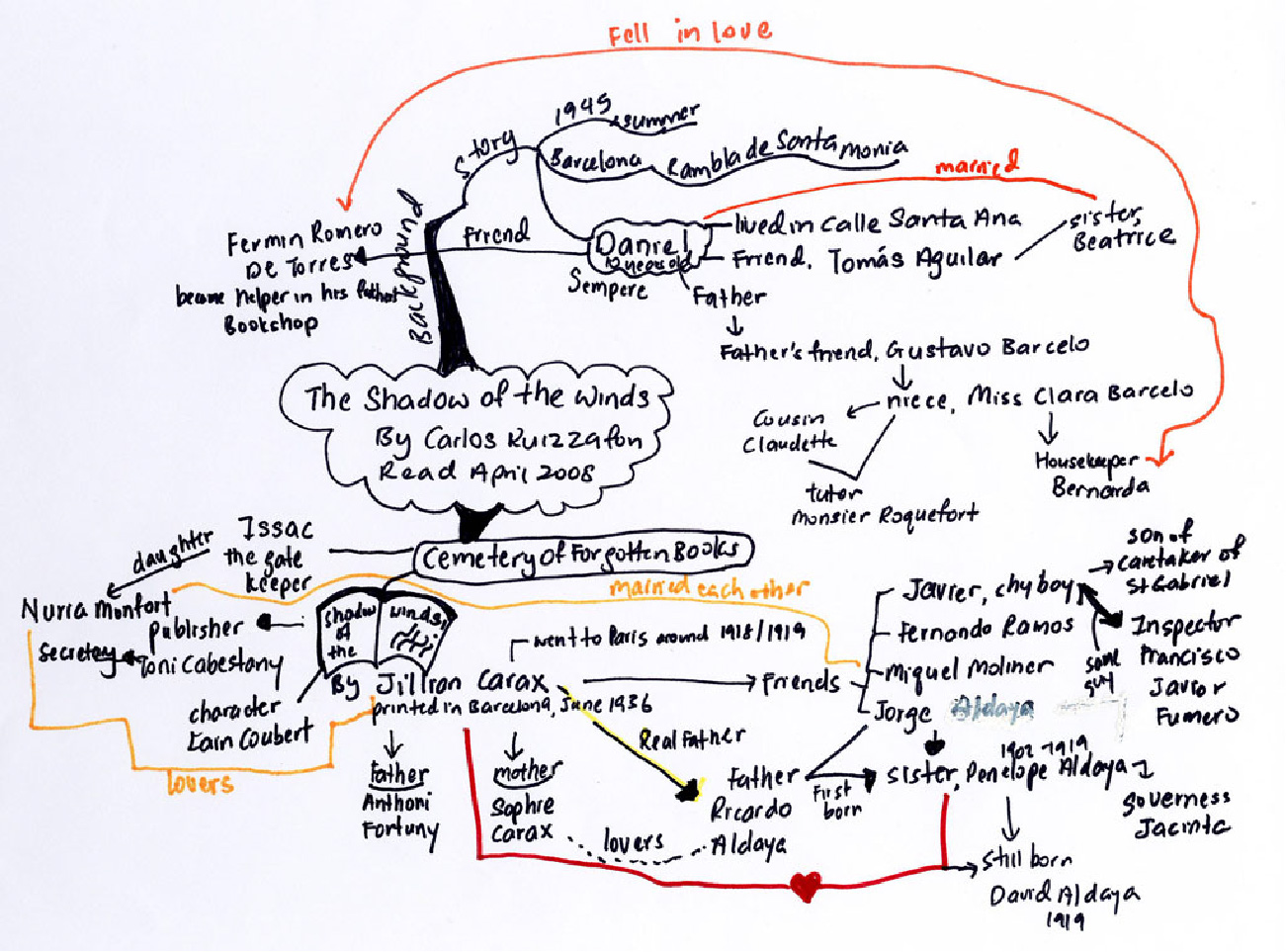

Concept Mapping and Visual Notetaking

One final notetaking method that appeals to learners who prefer a visual representation of notes is called mapping or sometimes mind mapping or concept mapping, although each of these names can have slightly different uses. Variations of this method abound, so you may want to look for more versions online, but the basic principles are that you are making connections between main ideas through a graphic depiction; some can get rather elaborate with colors and shapes, but a simple version may be more useful at least to begin. Main ideas can be circled or placed in a box with supporting concepts radiating off these ideas shown with a connecting line and possibly details of the support further radiating off the concepts. You can present your main ideas vertically or horizontally, but turning your paper long-ways, or in landscape mode, may prove helpful as you add more main ideas.

Figure 7.13 Concept mapping, sometimes referred to as mind mapping, can be an effective and very personalized approach to capturing information. (Credit: ArtistIvanChew / Flickr / Attribution 2.0 Generic (CC-BY 2.0))

You may be interested in trying visual notetaking or adding pictures to your notes for clarity. Sometimes when you can’t come up with the exact wording to explain something or you’re trying to add information for complex ideas in your notes, sketching a rough image of the idea can help you remember. According to educator Sherrill Knezel in an article entitled “The Power of Visual Notetaking,” this strategy is effective because “When students use images and text in notetaking, it gives them two different ways to pull up the information, doubling their chances of recall.” Don’t shy away from this creative approach to notetaking just because you believe you aren’t an artist; the images don’t need to be perfect. You may want to watch Rachel Smith’s TEDx Talk called “Drawing in Class” to learn more about visual notetaking.

You can play with different types of notetaking suggestions and find the method(s) you like best, but once you find what works for you, stick with it. You will become more efficient with the method the more you use it, and your notetaking, review, and test prep will become, if not easier, certainly more organized, which can delete decrease your anxiety.

Practicing Decipherable Shorthand

Most college students don’t take a class in shorthand, once the domain of secretaries and executive assistants, but maybe they should. That almost-lost art in the age of computers could come in very handy during intense notetaking sessions. Elaborate shorthand systems do exist, but you would be better served in your college notetaking adventures to hone a more familiar, personalized form of shorthand to help you write more in a shorter amount of time. Seemingly insignificant shortcuts can add up to ease the stress notetaking can induce—especially if you ever encounter an “I’m not going to repeat this” kind of presenter! Become familiar with these useful abbreviations:

|

Shortcut symbol |

Meaning |

|

w/, w/o, w/in |

with, without, within |

|

& |

and |

|

# |

number |

|

b/c |

because |

|

X, √ |

incorrect, correct |

|

Diff |

different, difference |

|

etc. |

and so on |

|

ASAP |

as soon as possible |

|

US, UK |

United States, United Kingdom |

|

info |

information |

|

Measurements: ft, in, k, m |

foot, inch, thousand, million |

|

¶ |

paragraph or new paragraph |

|

Math symbols: =, +, >, <, ÷ |

equal, plus, greater, less, divided by |

|

WWI, WWII |

World Wars I and II |

|

impt |

important |

|

?, !, ** |

denote something is very significant; don’t over use |

Do you have any other shortcuts or symbols that you use in your notes? Ask your parents if they remember any that you may be able to learn.

Annotating Notes After Initial Notetaking Session

Annotating notes after the initial notetaking session may be one of the most valuable study skills you can master. Whether you are highlighting, underlining, or adding additional notes, you are reinforcing the material in your mind and memory.

Admit it—who can resist highlighting markers? Gone are the days when yellow was the star of the show, and you had to be very careful not to press too firmly for fear of obliterating the words you were attempting to emphasize. Students now have a veritable rainbow of highlighting options and can color-code notes and text passages to their hearts’ content. Technological advances may be important, but highlighter color choice is monumental! Maybe.

The only reason to highlight anything is to draw attention to it, so you can easily pick out that ever-so-important information later for further study or reflection. One problem many students have is not knowing when to stop. If what you need to recall from the passage is a particularly apt and succinct definition of the term important to your discipline, highlighting the entire paragraph is less effective than highlighting just the actual term. And if you don’t rein in this tendency to color long passages (possibly in multiple colors) you can end up with a whole page of highlighted text. Ironically, that is no different from a page that is not highlighted at all, so you have wasted your time. Your mantra for highlighting text should be less is more. Always read your text selection first before you start highlighting anything. You need to know what the overall message is before you start placing emphasis in the text with highlighting.

Another way to annotate notes after initial notetaking is underlying significant words or passages. Albeit not quite as much fun as its colorful cousin highlighting, underlining provides precision to your emphasis.

Some people think of annotations as only using a colored highlighter to mark certain words or phrases for emphasis. Actually, annotations can refer to anything you do with a text to enhance it for your particular use (either a printed text, handwritten notes, or other sort of document you are using to learn concepts). The annotations may include highlighting passages or vocabulary, defining those unfamiliar terms once you look them up, writing questions in the margin of a book, underlining or circling key terms, or otherwise marking a text for future reference. You can also annotate some electronic texts.

Realistically, you may end up doing all of these types of annotations at different times. We know that repetition in studying and reviewing is critical to learning, so you may come back to the same passage and annotate it separately. These various markings can be invaluable to you as a study guide and as a way to see the evolution of your learning about a topic. If you regularly begin a reading session writing down any questions you may have about the topic of that chapter or section and also write out answers to those questions at the end of the reading selection, you will have a good start to what that chapter covered when you eventually need to study for an exam. At that point, you likely will not have time to reread the entire selection especially if it is a long reading selection, but with strong annotations in conjunction with your class notes, you won’t need to do that. With experience in reading discipline-specific texts and writing essays or taking exams in that field, you will know better what sort of questions to ask in your annotations.

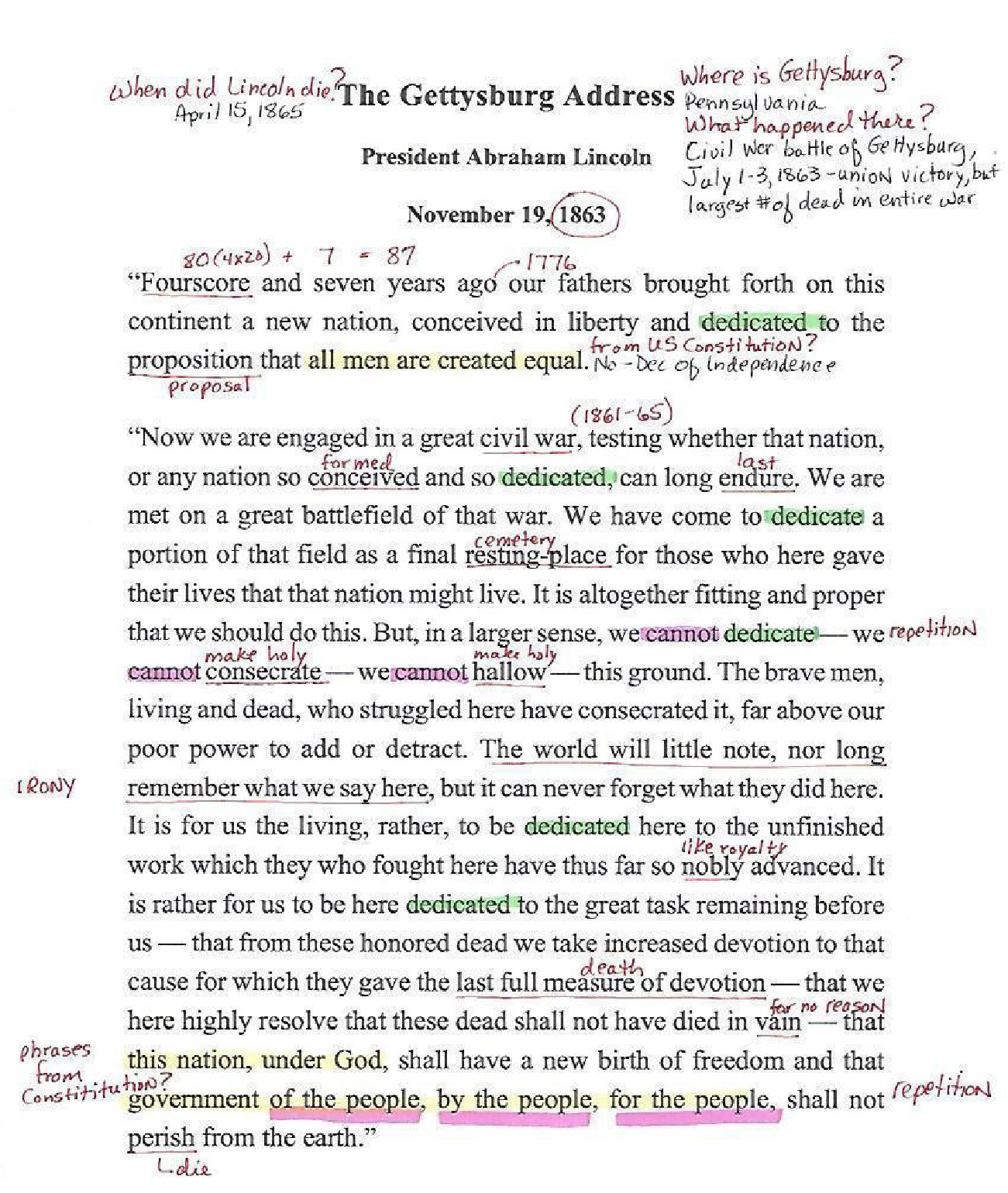

Figure 7.14 Annotations may include highlighting important topics, defining unfamiliar terms, writing questions in, underlining or circling key terms, or otherwise marking a text for future reference. Whichever approach you choose, try not to overdo it; neat, organized, and efficient notes are more effective than crowded or overdone notes.

Figure 7.15 While these notes may be meaningful to the person who took them, they are neither organized nor consistent. For example, note that some of the more commonly used terms, like “we” and “unfinished,” are defined, but less common ones — “consecrate” and “hallow” — are not.

What you have to keep in the front of your mind while you are annotating, especially if you are going to conduct multiple annotation sessions, is to not overdo whatever method you use. Be judicious about what you annotate and how you do it on the page, which means you must be neat about it. Otherwise, you end up with a mess of either color or symbols combined with some cryptic notes that probably took you quite a long time to create, but won’t be worth as much to you as a study aid as they could be. This is simply a waste of time and effort.

You cannot eat up every smidgen of white space on the page writing out questions or summaries and still have a way to read the original text. If you are lucky enough to have a blank page next to the beginning of the chapter or section you are annotating, use this, but keep in mind that when you start writing notes, you aren’t exactly sure how much space you’ll need. Use a decipherable shorthand and write only what you need to convey the meaning in very small print. If you are annotating your own notes, you can make a habit of using only one side of the paper in class, so that if you need to add more notes later, you could use the other side. You can also add a blank page to your notes before beginning the next class date in your notebook so you’ll end up with extra paper for annotations when you study.

Professional resources may come with annotations that can be helpful to you as you work through the various documentation requirements you’ll encounter in college as well. Purdue University’s Online Writing Lab (OWL) provides an annotated sample for how to format a college paper according to guidelines in the Modern Language Association (MLA) manual that you can see, along with other annotations.

Adding Needed Additional Explanations to Notes

Marlon was totally organized and ready to take notes in a designated course notebook at the beginning of every philosophy class session. He always dated his page and indicated what the topic of discussion was. He had various colored highlighters ready to denote the different note purposes he had defined: vocabulary in pink, confusing concepts in green, and note sections that would need additional explanations later in yellow. He also used his own shorthand and an impressive array of symbols to indicate questions (red question mark), highly probable test material (he used a tiny bomb exploding here), additional reading suggestions, and specific topics he would ask his instructor before the next class. Doing everything so precisely, Marlon’s methods seemed like a perfect example of how to take notes for success. Inevitably though, by the end of the hour-and-a-half class session, Marlon was frantically switching between writing tools, near to tears, and scouring his notes as waves of yellow teased him with uncertainty. What went wrong?

As with many of us who try diligently to do everything we know how to do for success or what we think we know because we read books and articles on success in between our course work, Marlon is suffering from trying to do too much simultaneously. It’s an honest mistake we can make when we are trying to save a little time or think we can multitask and kill two birds with one stone.

Unfortunately, this particular error in judgement can add to your stress level exponentially if you don’t step back and see it for what it is. Marlon attempted to take notes in class as well as annotate his notes to get them ready for his test preparation. It was too much to do at one time, but even if he could have done all those things during class, he’s missing one critical point about notetaking.

As much as we may want to hurry and get it over with, notetaking in class is just the beginning. Your instructor likely gave you a pre-class assignment to read or complete before coming to that session. The intention of that preparatory lesson is for you to come in with some level of familiarity for the topic under consideration and questions of your own. Once you’re in class, you may also need to participate in a group discussion, work with your classmates, or perform some other sort of lesson-directed activity that would necessarily take you away from taking notes. Does that mean you should ignore taking notes for that day? Most likely not. You may just need to indicate in your notes that you worked on a project or whatever other in-class event you experienced that date.

Very rarely in a college classroom will you engage in an activity that is not directly related to what you are studying in that course. Even if you enjoyed every minute of the class session and it was an unusual format for that course, you still need to take some notes. Maybe your first note could be to ask yourself why you think the instructor used that unique teaching strategy for the class that day. Was it effective? Was it worth using the whole class time? How will that experience enhance what you are learning in that course?

If you use an ereader or ebooks to read texts for class or read articles from the Internet on your laptop or tablet, you can still take effective notes. Depending on the features of your device, you have many choices. Almost all electronic reading platforms allow readers to highlight and underline text. Some devices allow you to add a written text in addition to marking a word or passage that you can collect at the end of your notetaking session. Look into the specific tools for your device and learn how to use the features that allow you to take notes electronically. You can also find apps on devices to help with taking notes, some of which you may automatically have installed when you buy the product. Microsoft’s OneNote, Google Keep, and the Notes feature on phones are relatively easy to use, and you may already have free access to those.

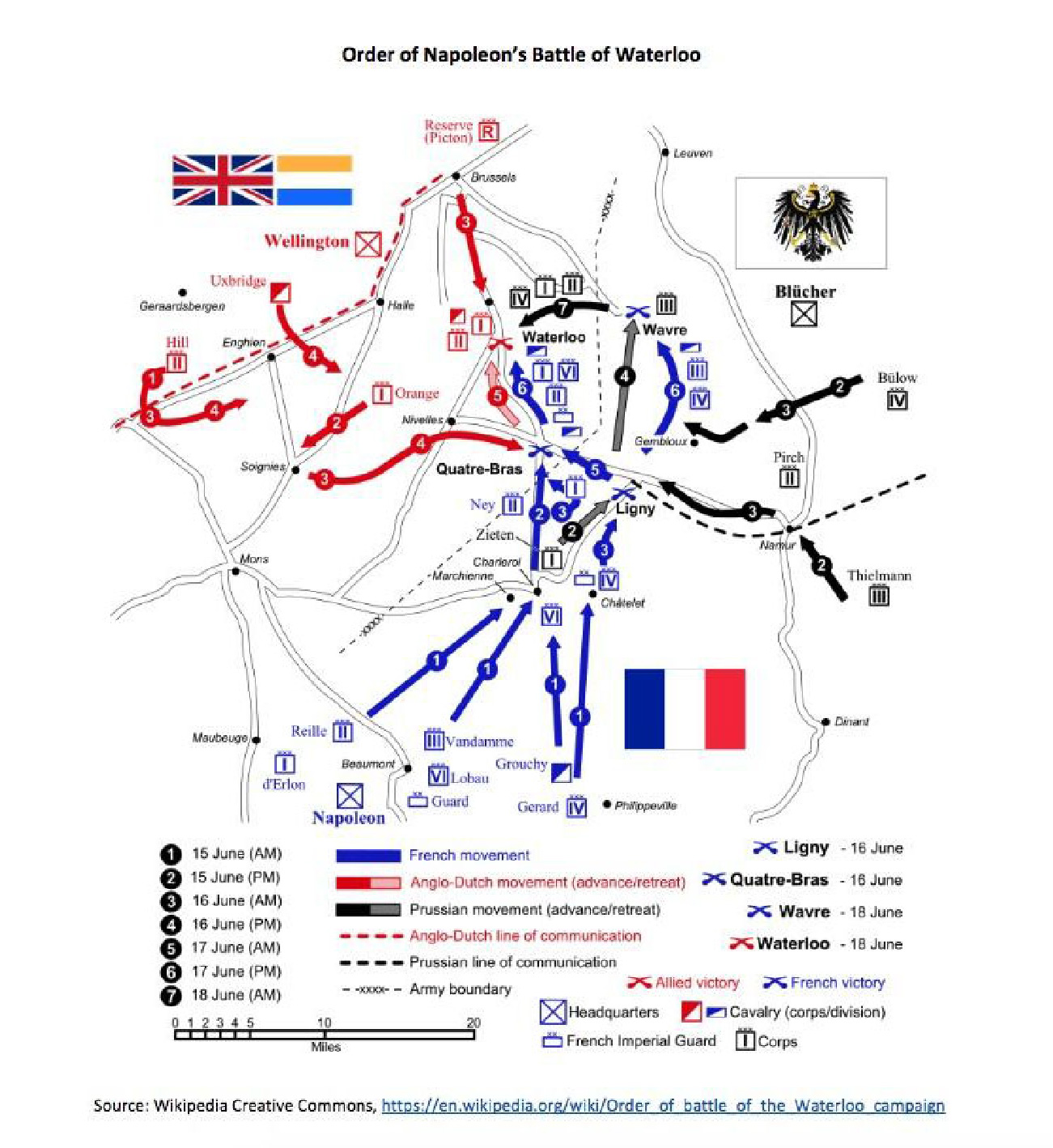

Taking Notes on Non-Text Items (i.e., Tables, Maps, Figures, etc.)

You may also encounter situations as you study and read textbooks, primary sources, and other resources for your classes that are not actually texts. You can still take notes on maps, charts, graphs, images, and tables, and your approach to these non-text features is similar to when you prepare to take notes over a passage of text. For example, if you are looking at the following map, you may immediately come up with several questions. Or it may initially appear overwhelming. Start by asking yourself these questions:

- What is the main point of this map?

- Who is the intended audience?

- Where is it?

- What time period does it depict?

- What does the map’s legend (the explanation of symbols) include?

- What other information do I need to make sense of this map?

Figure 7.16 Graphics, charts, graphs, and other visual items are also important to annotate. Not only do they often convey important information, but they may appear on exams or in other situations where you’ll need to use or demonstrate knowledge. Credit: “Lpankonin” / Wikipedia Commons / Attribution 3.0 Generic (CC BY 3.0)

You may want to make an extra copy of a graphic or table before you add annotations if you are dealing with a lot of information. Making sense of all the elements will take time, and you don’t want to add to the confusion.

Returning to Your Notes

Later, as soon as possible after the class, you can go back to your notes and add in missing parts. Just as you may generate questions as you’re reading new material, you may leave a class session or lecture or activities with many questions. Write those down in a place where they won’t get lost in all your other notes.

The exact timing of when you get back to the notes you take in class or while you are reading an assignment will vary depending on how many other classes you have or what other obligations you have in your daily schedule. A good starting place that is also easy to remember is to make every effort to review your notes within 24 hours of first taking them. Longer than that and you are likely to have forgotten some key features you need to include; must less time than that, and you may not think you need to review the information you so recently wrote down, and you may postpone the task too long.

Use your phone or computer to set reminders for all your note review sessions so that it becomes a habit and you keep on top of the schedule.

Your personal notes play a significant role in your test preparation. They should enhance how you understand the lessons, textbooks, lab sessions, and assignments. All the time and effort you put into first taking the notes and then annotating and organizing the notes will be for naught if you do not formulate an effective and efficient way to use them before sectional exams or comprehensive tests.

The whole cycle of reading, notetaking in class, reviewing and enhancing your notes, and preparing for exams is part of a continuum you ideally will carry into your professional life. Don’t try to take short cuts; recognize each step in the cycle as a building block. Learning doesn’t end, which shouldn’t fill you with dread; it should help you recognize that all this work you’re doing in the classroom and during your own study and review sessions is ongoing and cumulative. Practicing effective strategies now will help you be a stronger professional.

Activity

What resources can you find about reading and notetaking that will actually help you with these crucial skills? How do you go about deciding what resources are valuable for improving your reading and notetaking skills?

The selection and relative value of study guides and books about notetaking vary dramatically. Ask your instructors for recommendations and see what the library has available on this topic. The following list is not comprehensive, but will give you a starting point for books and articles on notetaking in college.

College Rules!: How to Study, Survive, and Succeed in College, by Sherri Nist-Olejnik and Jodi Patrick Holschuh. More than just notetaking, this book covers many aspects of transitioning into the rigors of college life and studying.

Effective Notetaking, by Fiona McPherson. This small volume has suggestions for using your limited time wisely before, during, and after notetaking sessions.