5 Knowing Yourself as a Learner

About This Chapter

In this chapter you will learn about the art of learning itself, as well as how to employ strategies that enable you to learn more efficiently.

After reading this chapter, you should be able to do the following:

- Discover the different types of learning and your learning practices.

- Make informed and effective learning choices in regards to personal engagement and motivation.

- Identify and apply the learning benefits of a growth mindset.

- Evaluate and make informed decisions about learning styles and learning skills.

- Recognize how personality type models influence learning and utilize that knowledge to improve your own learning.

- Identify the impact of outside circumstances on personal learning experiences and develop strategies to compensate for them.

- Recognize the presence of the “hidden curriculum” and how to navigate it.

5.1 The Power to Learn

Questions to consider:

- What actually happens to me when I learn something?

- Am I aware of different types of learning?

- Do I approach studying or practicing differently depending on the desired outcome?

Welcome to one of the most empowering chapters in this book! While each chapter focuses on showing you clear paths to success as a student, this one deals specifically with what is at the core of being a student: the act of learning.

We humans have been obsessed with how we learn and understand things since ancient times. Because of this, some of our earliest recorded philosophies have tried to explain how we take in information about the world around us, how we acquire new knowledge, and even how we can be certain what we learn is correct. This obsession has produced a large number of theories, ideas, and research into how we learn. There is a great deal of information out there on the subject—some of it is very good, and some of it, while well intentioned, has been a bit misguided.

Because of this obsession with learning, over the centuries, people have continually come up with new ideas about how we acquire knowledge. The result has been that commonly held “facts” about education have been known to change frequently. Often, what was once thought to be the newest, greatest discovery about learning was debunked later on. One well-known example of this is that of corporal punishment. For most of the time formal education has existed in our society, educators truly believed that beating students when they made a mistake actually helped them learn faster. Thankfully, birching (striking someone with a rod made from a birch tree) has fallen out of favor in education circles, and our institutions of learning have adopted different approaches. In this chapter, not only will you learn about current learning theories that are backed by neuroscience (something we did not have back in the days of birching), but you will also learn other learning theories that did not turn out to be as effective or as thoroughly researched as once thought. That does not mean those ideas about learning are useless. Instead, in these cases you find ways to separate the valuable parts from the myths to make good learning choices.

“Research has shown that one of the most influential aids in learning is an understanding about learning itself.”

What Is the Nature of Learning?

To begin with, it is important to recognize that learning is work. Sometimes it is easy and sometimes it is difficult, but there is always work involved. For many years people made the error of assuming that learning was a passive activity that involved little more than just absorbing information. Learning was thought to be a lot like copying and pasting words in a document; the student’s mind was blank and ready for an instructor to teach them facts that they could quickly take in. As it turns out, learning is much more than that. In fact, at its most rudimentary level, it is an actual process that physically changes our brains. Even something as simple as learning the meaning of a new word requires the physical alteration of neurons and the creation of new paths to receptors. These new electrochemical pathways are formed and strengthened as we utilize, practice, or remember what we have learned. If the new skill or knowledge is used in conjunction with other things we have already learned, completely different sections of the brain, our nerves, or our muscles may be tied in as a part of the process. A good example of this would be studying a painting or drawing that depicts a scene from a story or play you are already familiar with. Adding additional connections, memories, and mental associations to things you already know something about expands your knowledge and understanding in a way that cannot be reversed. In essence, it can be said that every time we learn something new we are no longer the same.

In addition to the physical transformation that takes place during learning, there are also a number of other factors that can influence how easy or how difficult learning something can be. While most people would assume that the ease or difficulty would really depend on what is being learned, there are actually several other factors that play a greater role.

In fact, research has shown that one of the most influential factors in learning is a clear understanding about learning itself. This is not to say that you need to become neuroscientists in order to do well in school, but instead, knowing a thing or two about learning and how we learn in general can have strong, positive results for your own learning. This is called metacognition (i.e., thinking about thinking).

Some of the benefits to how we learn can be broken down into different areas such as

- attitude and motivation toward learning,

- types of learning,

- methods of learning, and

- your own preferences for learning.

In this chapter you will explore these different areas to better understand how they may influence your own learning, as well as how to make conscious decisions about your own learning process to maximize positive outcomes.

All Learning Is Not the Same

The first, fundamental point to understand about learning is that there are several types of learning. Different kinds of knowledge are learned in different ways. Each of these different types of learning can require different processes that may take place in completely different parts of our brain.

For example, simple memorization is a form of learning that does not always require deeper understanding. Children often learn this way when they memorize poems or verses they recite. An interesting example of this can be found in the music industry, where there have been several hit songs sung in English by vocalists who do not speak English. In these cases, the singers did not truly understand what they were singing, but instead they were taught to memorize the sounds of the words in the proper order.

Figure 5.2 Learning has many levels and forms. For example, collaborative learning and showing your work require different skills and produce different results than reading or notetaking on your own. (Credit: StartUpStockPhotos / Pexels)

Memorizing sounds is a very different type of learning than, say, acquiring a deep understanding of Einstein’s general theory of relativity.

Notice in the comparative examples of music and physics that the different levels of learning are being defined by what they allow you to know or do. When classifying learning in this way, people usually agree on six different levels of learning. In this next section we will take a detailed look at each of these.

In the table below, the cells in the left column each contain one of the main levels of learning, categorized by what the learning allows you to do. To the right of each category are the “skill acquired” and a set of real-world examples of what those skills might be as applied to a specific topic. This set of categories is called Bloom’s Taxonomy, and it is often used as a guide for educators when they are determining what students should learn within a course.

|

Category of Learning |

Skill acquired |

Example 1: Musical ability |

Example 2: Historical information on Charles the Bald |

|

Create |

Produce new or original work |

Compose a piece of music |

Write a paper on Charles that draws a new conclusion about his reign |

|

Evaluate |

Justify or support an idea or decision |

Make critical decisions about the notes that make up a melody—what works, what doesn’t, and why |

Make arguments that support the idea that Charles was a good ruler |

|

Analyze |

Draw connections |

Play the specific notes that are found in the key of A |

Compare and contrast the historical differences between the reign of Charles and his grandfather, Charlemagne |

|

Apply |

Use information in new ways |

Use knowledge to play several notes that sound good together |

Use the information to write a historical account on the reign of Charles |

|

Understand/ Comprehend |

Explain ideas or concepts |

Understand the relationship between the musical notes and how to play each on a musical instrument |

Explain the historical events that enabled Charles to become Emperor |

|

Remember |

Recall facts and basic concepts |

Memorize notes on a musical scale |

Recall that Charles the Bald was Holy Roman Emperor from 875–877 CE |

Table 5.1

A review of the above table shows that actions in the left column (or what you will be able to do with the new knowledge) has a direct influence over what needs to be learned and can even dictate the type of learning approach that is best. For example, remembering requires a type of learning that allows the person basic memorization. In the case of Charles the Bald and his reign, it is simply a matter of committing the dates to memory. When it comes to understanding and comprehension, being able to explain how Charles came to power requires not only the ability to recall several events, but also for the learner to be able to understand the cause and effect of those events and how they worked together to make Charles emperor. Another example would be the ability to analyze. In this particular instance the information learned would not only be about Charles, but also about other rulers, such as Charlemagne. The information would have to be of such a depth that the learner could compare the events and facts about each ruler.

When you engage in any learning activity, take the time to understand what you will do with the knowledge once you have attained it. This can help a great deal when it comes to making decisions on how to go about it. Using flashcards to help memorize angles does not really help you solve problems using geometry formulas. Instead, practicing problem-solving with the actual formulas is a much better approach. The key is to make certain the learning activity fits your needs.

5.2 The Motivated Learner

Questions to consider:

- How do different types of motivation affect my learning?

- What is resilience and grit?

- How can I apply the Uses and Gratification Theory to make decisions about my learning?

- How do I prevent negative bias from hindering learning?

In this section, you will continue to increase your ability as an informed learner. Here you will explore how much of an influence motivation has on learning, as well as how to use motivation to purposefully take an active role in any learning activity. Rather than passively attempting to absorb new information, you will learn how to make conscious decisions about the methods of learning you will use (based on what you intend to do with the information), how you will select and use learning materials that are appropriate for your needs, and how persistent you will be in the learning activity.

There are three main motivation concepts that have been found to directly relate to learning. Each of these has been proven to mean the difference between success and failure. You will find that each of these is a strong tool that will enable you to engage with learning material in a way that not only suits your needs, but also gives you ownership over your own learning processes.

Resilience and Grit

While much of this chapter will cover very specific aspects about the act of learning, in this section, we will present different information that may at first seem unrelated. Some people would consider it more of a personal outlook than a learning practice, and yet it has a significant influence on the ability to learn.

What we are talking about here is called grit or resilience. Grit can be defined as personal perseverance toward a task or goal. In learning, it can be thought of as a trait that drives a person to keep trying until they succeed. It is not tied to talent or ability, but is simply a tendency to not give up until something is finished or accomplished.

Figure 5.3 U.S. Army veteran and captain of the U.S. Invictus team, Will Reynolds, races to the finish line. (Credit: DoD News / Flickr / Attribution 2.0 Generic (CC-BY 2.0))

The study showed that grit and perseverance were better predictors of academic success and achievement than talent or IQ.

This personality trait was defined as “grit” by the psychologist Angela Duckworth.[1] In a 2007 study Duckworth and colleagues found that individuals with high grit were able to maintain motivation in learning tasks despite failures. The study examined a cross section of learning environments, such as GPA scores in Ivy League universities, dropout rates at West Point, rankings in the National Spelling Bee, and general educational attainment for adults. What the results showed was that grit and perseverance were better predictors of academic success and achievement than talent or IQ.

Applying Grit

The concept of grit is an easy one to dismiss as something taken for granted. In our culture, we have a number of sayings and aphorisms that capture the essence of grit: “If at first you do not succeed, try, try again,” or the famous quote by Thomas Edison: “Genius is one percent inspiration, ninety-nine percent perspiration.”

The problem is we all understand the concept, but actually applying it takes work. If the task we are trying to complete is a difficult one, it can take a lot of work.

The first step in applying grit is to adopt an attitude that looks directly to the end goal as the only acceptable outcome. With this attitude comes an acceptance that you may not succeed on the first attempt—or the nineteenth attempt. Failed attempts are viewed as merely part of the process and seen as a very useful way to gain knowledge that moves you toward success. An example of this would be studying for an exam. In your first attempt at studying you simply reread the chapters of your textbook covered in the exam. You find that while this reinforces some of the knowledge you have gained, it does not ensure you have all the information you will need to do well on the test. You know that if you simply read the chapters yet again, there is no guarantee you are going to be any more successful. You determine that you need to find a different approach. In other words, your first attempt was not a complete failure, but it did not achieve the end goal, so you try again with a different method.

On your second try, you copy down all of the main points onto a piece of paper using the section headlines from the chapters. After a short break you come back to your list and write down a summary of what you know about each item on your list. This accomplishes two things: first, you are able to immediately spot areas where you need to learn more, and second, you can check your summaries against the text to make certain what you know is correct and adequate. In this example, while you may not have yet achieved complete success, you will have learned what you need to do next.

In true grit fashion, for your next try, you study those items on your list where you found you needed a bit more information, and then you go through your list again. This time you are able to write down summaries of all the important points, and you are confident you have the knowledge you need to do well on the exam. After this, you still do not stop, but instead you change your approach to use other methods that keep what you have learned fresh in your mind.

Keeping Grit in Mind: Grit to GRIT

The concept of grit has been taken beyond the original studies of successful learning. While the concept of grit as a personality trait was originally recognized as something positive in all areas of activity, encouraging grit became very popular in education circles as a way to help students become more successful. In fact, many of those that were first introduced to grit through education have begun applying it to business, professional development, and their personal lives. Using a grit approach and working until the goal is achieved has been found to be very effective in not only academics, but in many other areas.[2]

The New York Times best-selling author Paul G. Stoltz has taken grit and turned it into an acronym (GRIT) to help people remember and use the attributes of a grit mindset.[3] His acronym is Growth, Resilience, Instinct, and Tenacity. Each of these elements is explained in the table below.

|

Growth |

Your propensity to seek and consider new ideas, additional alternatives, different approaches, and fresh perspectives |

|

Resilience |

Your capacity to respond constructively and ideally make use of all kinds of adversity |

|

Instinct |

Your gut-level capacity to pursue the right goals in the best and smartest ways |

|

Tenacity |

The degree to which you persist, commit to, stick with, and go after whatever you choose to achieve |

Table 5.2 The GRIT acronym as outlined by Paul G. Stoltz

There is one other thing to keep in mind when it comes to applying grit (or GRIT) to college success. The same sort of persevering approach can not only be used for individual learning activities, but can be applied to your entire degree. An attitude of tenacity and “sticking with it” until you reach the desired results works just as well for graduation as it does for studying for an exam.

How Do You Get Grit?

A quick Internet search will reveal that there are a large number of articles out there on grit and how to get it. While these sources may vary in their lists, most cover about five basic ideas that all touch upon concepts emphasized by Duckworth. What follows is a brief introduction to each. Note that each thing listed here begins with a verb. In other words, it is an activity for you to do and keep doing in order to build grit.

1. Pursue what interests you.

Personal interest is a great motivator! People tend to have more grit when pursuing things that they have developed an interest in.

2. Practice until you can do it, and then keep practicing.

The idea of practicing has been applied to every skill in human experience. The reason everyone seems to be so fixated with practice is because it is effective and there is no “grittier” activity.

3. Find a purpose in what you do.

Purpose is truly the driver for anything we pursue. If you have a strong purpose in any activity, you have reason to persist at it. Think in terms of end goals and why doing something is worth it. Purpose answers the question of “Why should I accomplish this?”

4. Have hope in what you are doing.

Have hope in what you are doing and in how it will make things different for you or others. While this is somewhat related to purpose, it should be viewed as a separate and positive overall outlook in regard to what you are trying to achieve. Hope gives value to purpose. If purpose is the goal, hope is why the goal is worth attaining at all.

5. Surround yourself with gritty people.

Persistence and tenacity tend to rub off on others, and the opposite does as well. As social creatures we often adopt the behaviors we find in the groups we hang out with. If you are surrounded by people that quit early, before achieving their goals, you may find it acceptable to give up early as well. On the other hand, if your peers are all achievers with grit, you will tend to exhibit grit yourself.

Application

Get a Grit Partner

It is an unfortunate statistic that far too many students who begin college never complete their degree. Over the years a tremendous amount of research has gone into why some students succeed while others do not. After reading about grit, you will probably not be surprised to learn that the research has shown it to not only be a major contributor of learning but to be one of the strongest factors contributing to student graduation.

While that may seem obvious since, by definition, grit is a tendency to keep going until you reach your goal, there was something very significant that turned up in the details of a study conducted by American College Testing (also known as ACT). ACT is a nonprofit organization that administers the college admissions test by the same name, and they have been looking at over 50 years of student persistence data to figure out why some students complete college while others do not. What they have found is that the probability a student will stay in college is tied directly to social connections.[4] In other words, students that found someone they connected with and that provided a sense of accountability dramatically increased their grit. It did not matter if the person was another student, an instructor, or someone else. What did matter is that they felt a strong motivation to keep working, even when their college experience was at its most difficult. It has been surmised that from a psychological perspective, the extra grit comes from not wanting to disappoint the person they have connected with. Regardless of the reason, the data show that having a grit partner is one of the most effective ways to statistically increase your chances of graduation.

A grit partner does not have to be a formal relationship. Your partner can simply be a classmate—someone that you can talk with. It can be an instructor you admire or someone else that you establish a connection with. It can even be a family member who will encourage you—someone you do not want to disappoint. What you are looking for is someone who will help motivate you, either by their example or by their willingness to give you a pep talk when you need it. The key is that it is someone you respect and who will encourage you to do well in school.

Right now, think about someone who could be your grit partner. Keep in mind that you may not have the same grit partner throughout your entire college experience. You may begin with another classmate but later find that a school staff member steps into the role. Later, as you near graduation, you may find that your favorite instructor motivates you more to do well in school than anyone else. Regardless, the importance of finding the social connection that helps your grit is important.

Uses and Gratification Theory and Learning

In the middle of the last century, experts held some odd beliefs that we might find exceptionally strange in our present age. For example, many scholars were convinced that not only was learning a passive activity, but that mass media such as movies, television, and newspapers held significant control over us as individuals. The thinking at that time was that we were helpless to think for ourselves or make choices about learning or the media we consumed. The idea was that we just simply ingested information fed to us and we were almost completely manipulated by it.

What changed this way of thinking was a significant study on audience motivations for watching different political television programs.[5] The study found that not only did people make decisions about what information they consumed, but they also had preferences in content and how it was delivered. In other words, people were active in their choices about information. What is more important is that the research began to show that our own needs, goals, and personal opinions are bigger drivers for our choices in information than anything else. This gave rise to what became known as the Uses and Gratification Theory (UGT).

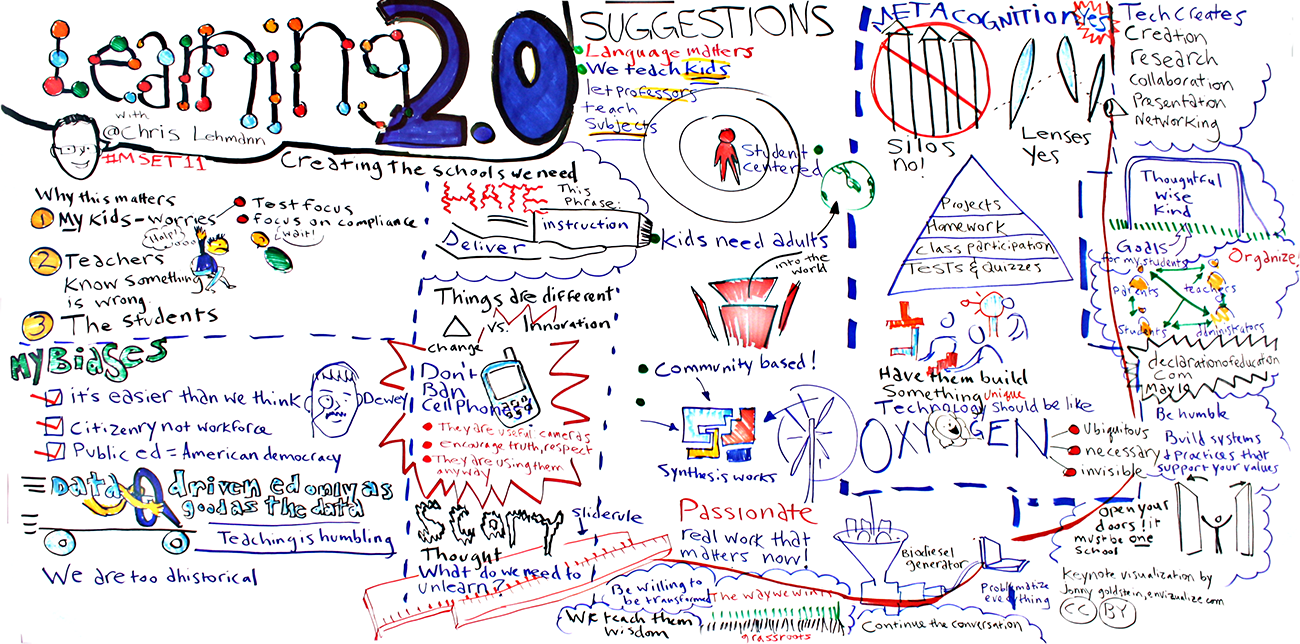

Figure 5.4 Concept maps, or idea clusters, are used to gather and connect ideas. The exercise of creating, recreating, and improving them can be an excellent way to build and internalize a deeper knowledge of subjects. (Credit: Johnny Goldstien / Flickr / Attribution 2.0 Generic (CC-BY 2.0))

At first, personal choices about television programs might seem a strange topic for a chapter on learning, but if you think about it, learning at its simplest is the consumption of information to meet a specific need. You choose to learn something so you can attain certain goals. This makes education and UGT a natural fit.

Applying UGT to education is a learner-centered approach that focuses on helping you take control of how and what you learn. Not only that, but it gives you a framework as an informed learner and allows you to choose information and learning activities with the end results in mind. The next section examines UGT a little more closely and shows how it can be directly applied to learning.

The Uses and Gratification Model

The Uses and Gratification model is how people are thought to react according to UGT. It considers individual behavior and motivation as the primary driver for media consumption. In education this means that the needs of the learner are what determine the interaction with learning content such as textbooks, lectures, and other information sources. Since any educational program is essentially content and delivery (the same as with any media), the Uses and Gratification model can be applied to meet student needs, student satisfaction, and student academic success. This is something that is not recognized in many other learning theories since they begin with the premise that it is learning content and how it is delivered that influences the learner more than the learner’s own wants and expectations.

The main assumption of the Uses and Gratification model is that media consumers will seek out and return to specific media sources based on a personal need. For learners this is exceptionally useful since it gives an insight and the ability to positively influence their own motivations, expectations, and the perceived value of their education.

Figure 5.5 The Uses and Gratification model indicates that people will actively seek out and integrate specific media into their lives. (Credit: Garry Knight / Flickr / Attribution 2.0 Generic (CC-BY 2.0))

If you understand the key concepts of the Uses and Gratification model, you can make informed decisions about your own learning: how you learn, which materials you use to learn, and what motivates you to learn. An illustration of this was found in the example given in the previous section on grit. There, a series of exam study activities were presented—first reading the appropriate chapters, then making a list of chapter concepts and reviewing what was known, then returning to learn the information needed to fill the gaps. Each activity was chosen by the learner based on how well it fit their needs to help reach the goal of doing well on an exam.

Here we should offer a brief word of caution about being wary when choosing materials and media. There is a great deal of misleading and inaccurate information presented via the Internet and social media. Making informed decisions about your learning and the material you consume includes checking sources and avoiding information that is not credible.

“We are able to consciously make learning choices based on our own identified needs and what we hope to gain by that learning.”

In his book Key Themes in Media Theory,[6] Dan Laughey presents the UGT model according to its original authors as a single sentence that divides each area of influence into the following concerns:

Social and psychological origins of …

- needs, which generate …

- expectations of …

- the mass media or other sources, which lead to …

- differential patterns of media exposure, resulting in …

- needs gratification and …

- other unintended consequences.

Taken as a list or a single sentence, this can be a bit overwhelming to digest. There are many things being said at the same time, and they may not all be immediately clear. To better understand what each of the “areas of concern” are and how they can impact learning, each has been separated and explained in the table below.

|

Area of Concern |

What it means for you |

How it applies to learning |

Real-world example |

|

1. Social and psychological origins of … |

Your motivations, not only as a student but as a person, and both the social and psychological factors that influence you |

This can be everything from the original motivation behind enrolling in school in the first place, down to more specific goals like why you want to learn to write and communicate well. |

A drive to be self-supporting and to take on a productive role in society. |

|

2. needs, which generate … |

Better job, increased income, satisfying career, prestige |

This can include the area of study you select and the school you choose to attend. |

Pursuing a degree to seek a career in a field you enjoy. |

|

3. expectations of … |

Expectation and perception (preconceived and continuing) of educational material |

What you expect to learn to fulfill goals and meet needs. |

Understanding what you need to accomplish the smaller goals. An example would be “study for an exam.” |

|

4. the mass media or other sources, which lead to… |

The content and learning activities of the program |

Selection of content aimed at fulfilling needs. Results are student satisfaction, perceived value, and continued enrollment. |

Choosing which learning activities to use (e.g., texts, watch videos, research alternative content, etc.). |

|

5. differential patterns of media exposure, resulting in … |

Frequency and level of participation |

How you engage with learning activities and how often. Results are student satisfaction and perceived value, and continued enrollment. |

When, how often, and how much time you spend in learning activities. |

|

6. needs gratification and … |

Better job, increased income, satisfying career, prestige, more immediate goals like pass an exam, earn a good grade, etc. |

Needs fulfillment and completion of goals. |

Learning activities that meet your learning needs, including fulfillment of your original goals. |

|

7. other unintended consequences. |

Increased skills and knowledge, entertainment, social involvement and networking |

Causes positive loop-back into 4, 5, and 6, reinforcing those positive outcomes. |

Things you learn beyond your initial goals. |

Table 5.3

What to Do with UGT

On the surface, UGT may seem overly complex, but this is due to its attempt to capture everything that influences how and why we take in information. At this point in your understanding, the main thing to focus on is the bigger idea that our motivations, our end goals, and our expectations are what drive us to learn. If we are aware of these motivations, we can use them to make influential decisions about what we learn and how we learn.

One of the things that will become apparent as you continue reading this chapter and doing the included activities is that all of it fits within the UGT model. Everything about learning styles, your own attitude about learning, how you prefer to learn, and what you get out of it are covered in UGT. Being familiar with it gives you a way to identify and apply everything else you will learn about learning. As you continue in this chapter, rather than looking at each topic as a stand-alone idea, think about where each fits in the Uses and Gratification model. Does it influence your motivations, or does it help you make decisions about the way you learn? This way UGT can provide a way for you to see the value and how to apply everything you learn from this point forward and for every learning experience along the way.

If you were going to define how UGT applies to learning with a few quick statements, it would look something like this:

UGT asks:

- What is it that motivates you to learn something?

- What need does it fulfill?

- What do you expect to have happen with certain learning activities?

- How can you choose the right learning activities to better ensure you meet your needs and expectations?

- What other things might result from your choices?

Analysis Question

Take a moment to think about your own choices when it comes to consuming media. Are there certain sources you prefer? Why? What needs or gratifications do those particular sources fulfill in a way that others do not? Now, use the same process to analyze your current college experience. Are there certain classes or activities you like more than others? Why? Do any of your reasons have to do with the needs or gratifications the classes or learning activities fulfill?

After you have answered those questions, you can always step beyond mere analysis and determine what you could change to make the classes or activities you enjoy less better fulfill your needs.

Combating Negative Bias

In addition to being a motivated learner through the use of grit and UGT, there is a third natural psychological tendency you should be aware of. It is a tendency that you should guard against. Ignoring the fact that it exists can not only adversely affect learning, but it can set up roadblocks that may prevent you from achieving many goals. This tendency is called negative bias.

Negative bias is the psychological trait of focusing on the negative aspects of a situation rather than the positive. An example of this in a learning environment would be earning a 95 percent score on an assignment but obsessing over the 5 percent of the points that were missed. Another example would be worrying and thinking negative thoughts about yourself over a handful of courses where you did not do as well as in others—so much so that you begin to doubt your abilities altogether.

Figure 5.6 Some level of worry and concern is natural, but an overwhelming amount of negative thoughts about yourself, including doubt in your abilities and place in school, can impede your learning and stifle your success. You can develop strategies to recognize and overcome these feelings. (Credit: Inzmam Kahn / Pexels)

Unfortunately, this is a human tendency that can often overwhelm a student. As a pure survival mechanism it does have its usefulness in that it reminds us to be wary of behaviors that can result in undesirable outcomes. Imagine that as a child playing outside, you have seen dozens if not hundreds of bees over the years. But once, out of all those other times, you were stung by a single bee. Now, every time you see a bee you recall the sting, and you now have a negative bias toward bees in general. Whenever possible you avoid bees altogether.

It is easy to see how this psychological system could be beneficial in those types of situations, but it can be a hindrance in learning since a large part of the learning process often involves failure on early attempts. Recognizing this is a key to overcoming negative bias. Another way to combat negative bias is to purposefully focus on successes and to acknowledge earlier attempts that fail as just a part of the learning.

What follows are a few methods for overcoming negative bias and negative self-talk. Each focuses on being aware of any negative attitude or emphasizing the positive aspects in a situation.

Be aware of any negative bias. Keep an eye out for any time you find yourself focusing on some negative aspect, whether toward your own abilities or on some specific situation. Whenever you recognize that you are exhibiting a negative bias toward something, stop and look for the positive parts of the experience. Think back to what you have learned about grit, how any lack of success is only temporary, and what you have learned that gets you closer to your goal.

Focus on the positive before you begin. While reversing the impact of negative bias on your learning is helpful, it can be even more useful to prevent it in the first place. One way to do this is to look for the positives before you begin a task. An example of this would be receiving early feedback for an assignment you are working on. To accomplish this, you can often ask your instructor or one of your classmates to look over your work and provide some informal comments. If the feedback is positive then you know you are on the right track. That is useful information. If the feedback seems to indicate that you need to make a number of corrections and adjustments, then that is even more valuable information, and you can use it to greatly improve the assignment for a much better final grade. In either case, accurate feedback is what you really want most, and both outcomes are positive for you.

Keep a gratitude and accomplishment journal. Again, the tendency to recall and overemphasize the negative instances while ignoring or forgetting about the positive outcomes is the nature of negative bias. Sometimes we need a little help remembering the positives, and we can prompt our memories by keeping a journal. Just as in a diary, the idea is to keep a flowing record of the positive things that happen, the lessons you learned from instances that were “less than successful,” and all accomplishments you make toward learning. In your journal you can write or paste anything that you appreciated or that has positive outcomes. Whenever you are not feeling up to a challenge or when negative bias is starting to wear on you, you can look over your journal to remind yourself of previous accomplishments in the face of adversity.

Analysis Question

Building the Foundation

In this section you read about three major factors that contribute to your motivation as a learner: grit and perseverance, your own motivations for learning (UGT), and the pitfalls of negative bias. Now it is time to do a little self-analysis and reflection.

Which of these three areas do you feel strongest in? Are you a person that naturally has grit, or do you better understand your own motivations for learning (using UGT)? Do you struggle with negativity bias, or is it something that you rarely have to deal with?

Determine in which of these areas you are strongest, and think about what things make you so strong. Is it a positive attitude (you always see the glass as half full as opposed to half empty), or do you know exactly why you are in college and exactly what you expect to learn?

After you have analyzed your strongest area, then do the same for the two weaker ones. What makes you susceptible to challenges in these areas? Do you have a difficult time sticking with things or possibly focus too much on the negative? Look back at the sections on your two weakest areas, and put together a plan for overcoming them. For each one, choose a behavior you intend to change and think of some way you will change it.

5.3 It’s All in the Mindset

Questions to consider:

- What is a growth mindset, and how does it affect my learning?

- What are performance goals versus learning goals?

In the previous sections of this chapter you have focused on a number of concepts and models about learning. One of the things they all have in common is that they utilize different approaches to education by presenting new ways to think about learning. In each of these, the common element has been a better understanding of yourself as a learner and how to apply what you know about yourself to your own learning experience. If you were to distill all that you have learned in this chapter so far down to a single factor, it would be about using your mindset to your best advantage. In this next section, you will examine how all of this works in a broader sense by learning about the significance of certain mindsets and how they can hinder or promote your own learning efforts.

Figure 5.7 Many fields of study and work create intersections of growth and fixed mindset. People may feel great ability to grow and learn in some areas, like art and communication, but feel more limited in others, such as planning and financials. Recognizing these intersections will help you approach new topics and tasks. (Credit: mentatdgt / Pexels)

Performance vs. Learning Goals

As you have discovered in this chapter, much of our ability to learn is governed by our motivations and goals. What has not yet been covered in detail has been how sometimes hidden goals or mindsets can impact the learning process. In truth, we all have goals that we might not be fully aware of, or if we are aware of them, we might not understand how they help or restrict our ability to learn. An illustration of this can be seen in a comparison of a student that has performance-based goals with a student that has learning-based goals.

If you are a student with strict performance goals, your primary psychological concern might be to appear intelligent to others. At first, this might not seem to be a bad thing for college, but it can truly limit your ability to move forward in your own learning. Instead, you would tend to play it safe without even realizing it. For example, a student who is strictly performance-goal-oriented will often only says things in a classroom discussion when they think it will make them look knowledgeable to the instructor or their classmates. For example, a performance-oriented student might ask a question that she knows is beyond the topic being covered (e.g., asking about the economics of Japanese whaling while discussing the book Moby Dick in an American literature course). Rarely will they ask a question in class because they actually do not understand a concept. Instead they will ask questions that make them look intelligent to others or in an effort to “stump the teacher.” When they do finally ask an honest question, it may be because they are more afraid that their lack of understanding will result in a poor performance on an exam rather than simply wanting to learn.

If you are a student who is driven by learning goals, your interactions in classroom discussions are usually quite different. You see the opportunity to share ideas and ask questions as a way to gain knowledge quickly. In a classroom discussion you can ask for clarification immediately if you don’t quite understand what is being discussed. If you are a person guided by learning goals, you are less worried about what others think since you are there to learn and you see that as the most important goal.

Another example where the difference between the two mindsets is clear can be found in assignments and other coursework. If you are a student who is more concerned about performance, you may avoid work that is challenging. You will take the “easy A” route by relying on what you already know. You will not step out of your comfort zone because your psychological goals are based on approval of your performance instead of being motivated by learning.

This is very different from a student with a learning-based psychology. If you are a student who is motivated by learning goals, you may actively seek challenging assignments, and you will put a great deal of effort into using the assignment to expand on what you already know. While getting a good grade is important to you, what is even more important is the learning itself.

If you find that you sometimes lean toward performance-based goals, do not feel discouraged. Many of the best students tend to initially focus on performance until they begin to see the ways it can restrict their learning. The key to switching to learning-based goals is often simply a matter of first recognizing the difference and seeing how making a change can positively impact your own learning.

What follows in this section is a more in-depth look at the difference between performance- and learning-based goals. This is followed by an exercise that will give you the opportunity to identify, analyze, and determine a positive course of action in a situation where you believe you could improve in this area.

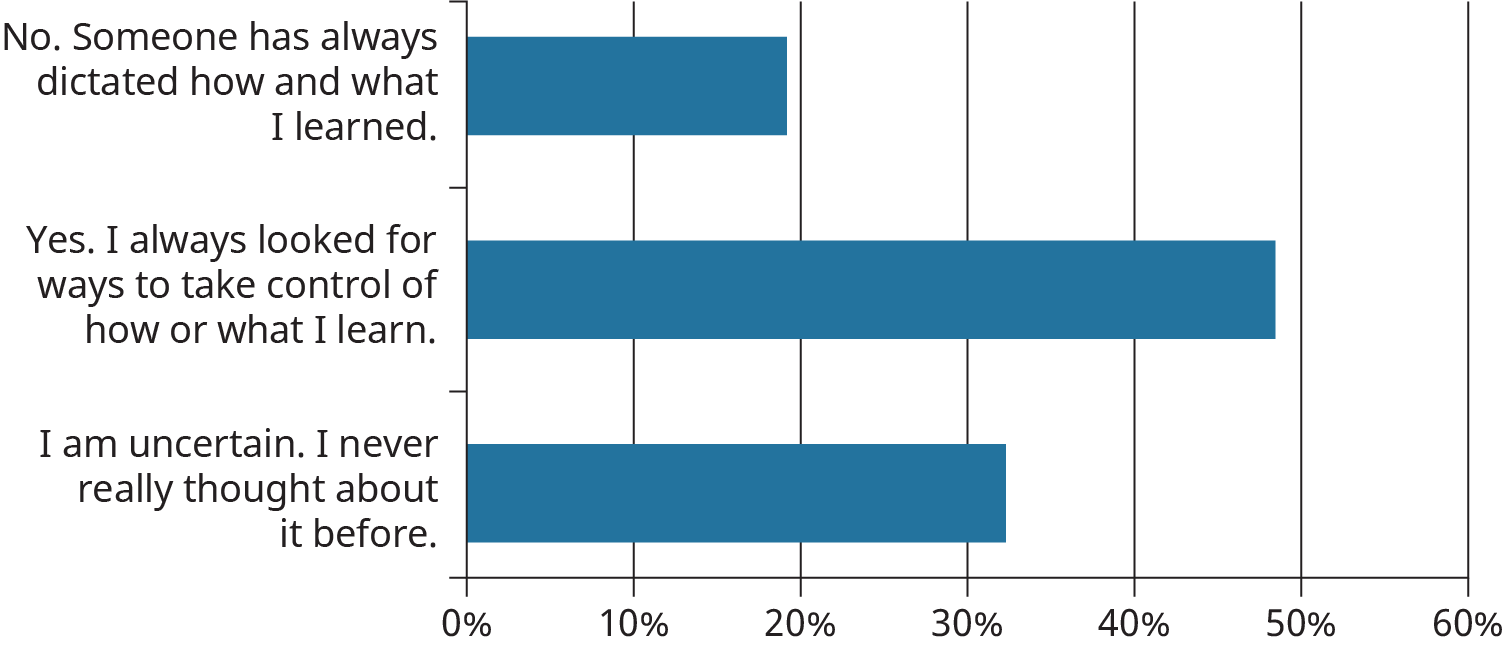

What Students Say

- In the past, did you feel like you had control over your own learning?

- No. Someone has always dictated how and what I learned.

- Yes. I always look for ways to take control of what and how I learned.

- I am uncertain. I never thought about it before.

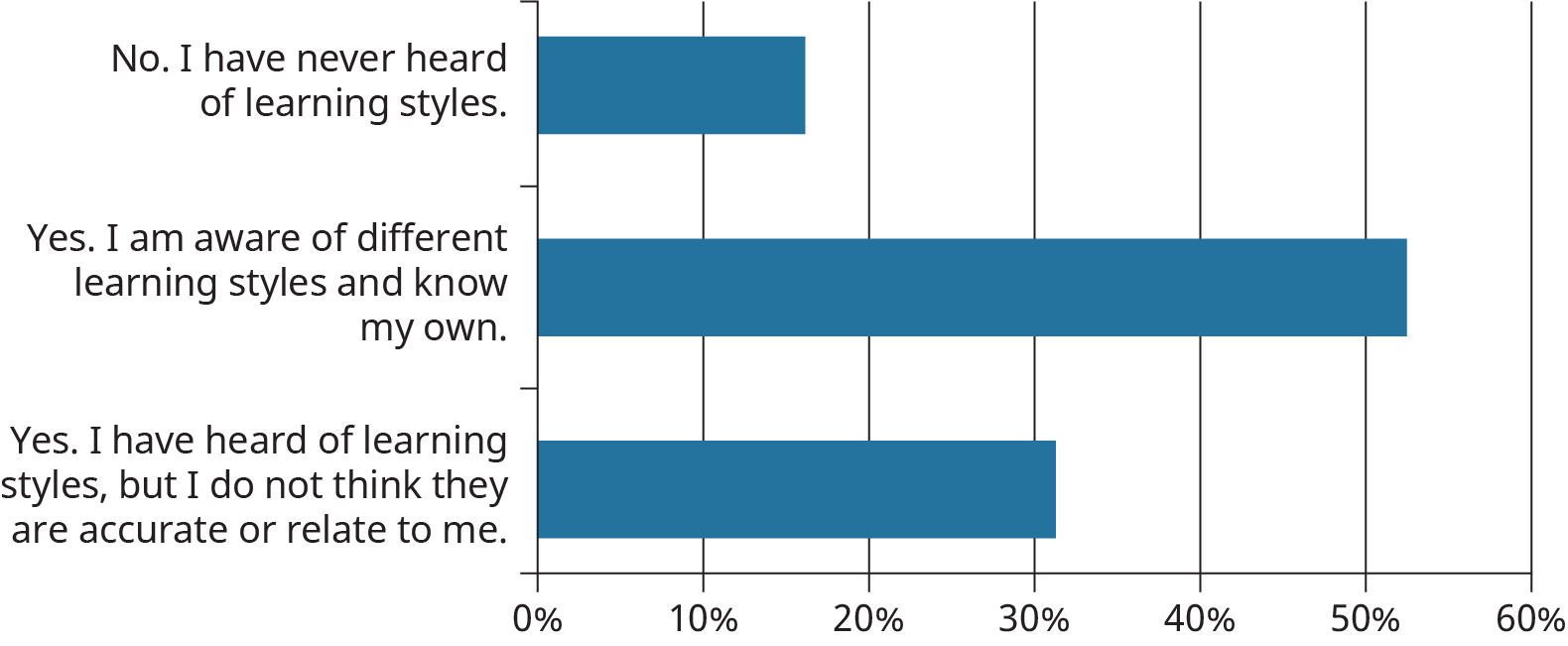

- Have you ever heard of learning styles or do you know your own learning style?

- No. I have never heard of learning styles.

- Yes. I have heard of learning styles and know my own.

- Yes. I have heard of learning styles, but I don’t think they’re accurate or relate to me.

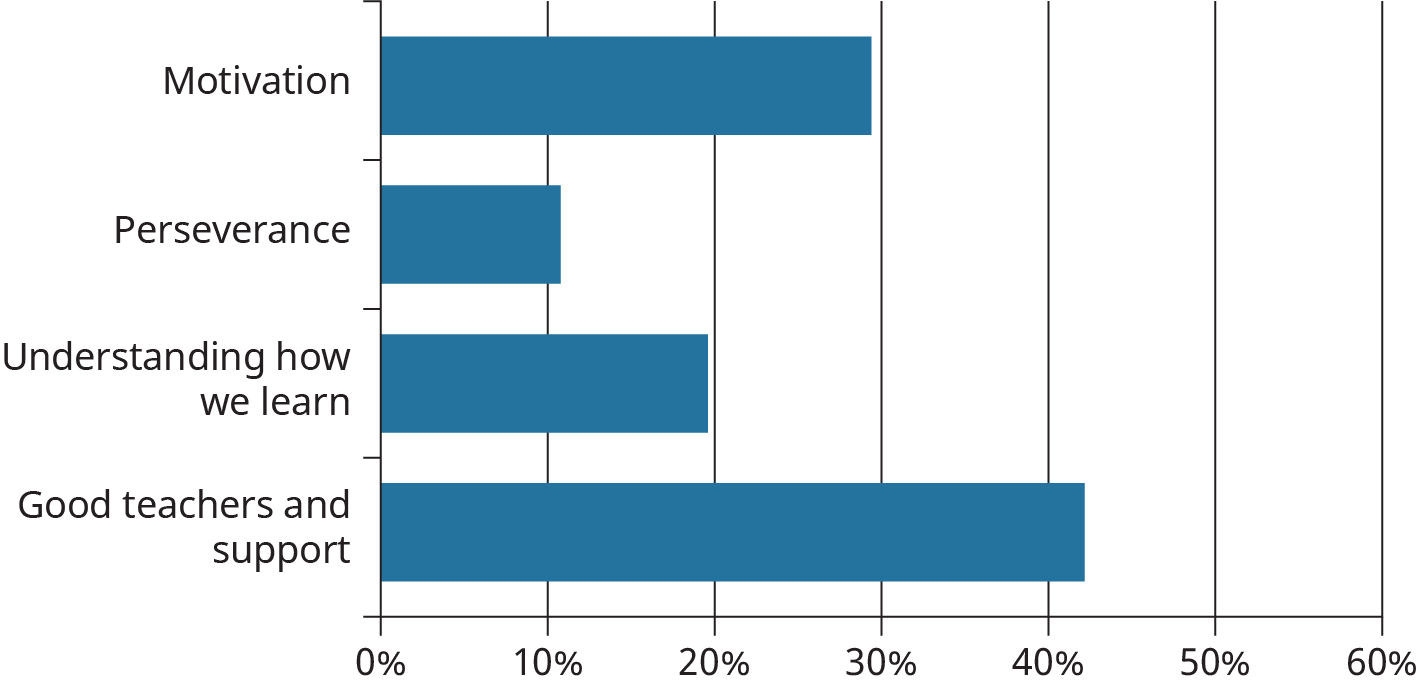

- Which factors other than intelligence do you think have the greatest influence on learning?

- Motivation

- Perseverance

- Understanding how I learn

- Good teachers and support

Students offered their views on these questions, and the results are displayed in the graphs below.

In the past, did you feel like you had control over your own learning?

Figure 5.8

Have you ever heard of learning styles or do you know your own learning style?

Figure 5.9

Which factors other than intelligence do you think have the greatest influence on learning?

Figure 5.10

Fixed vs. Growth Mindset

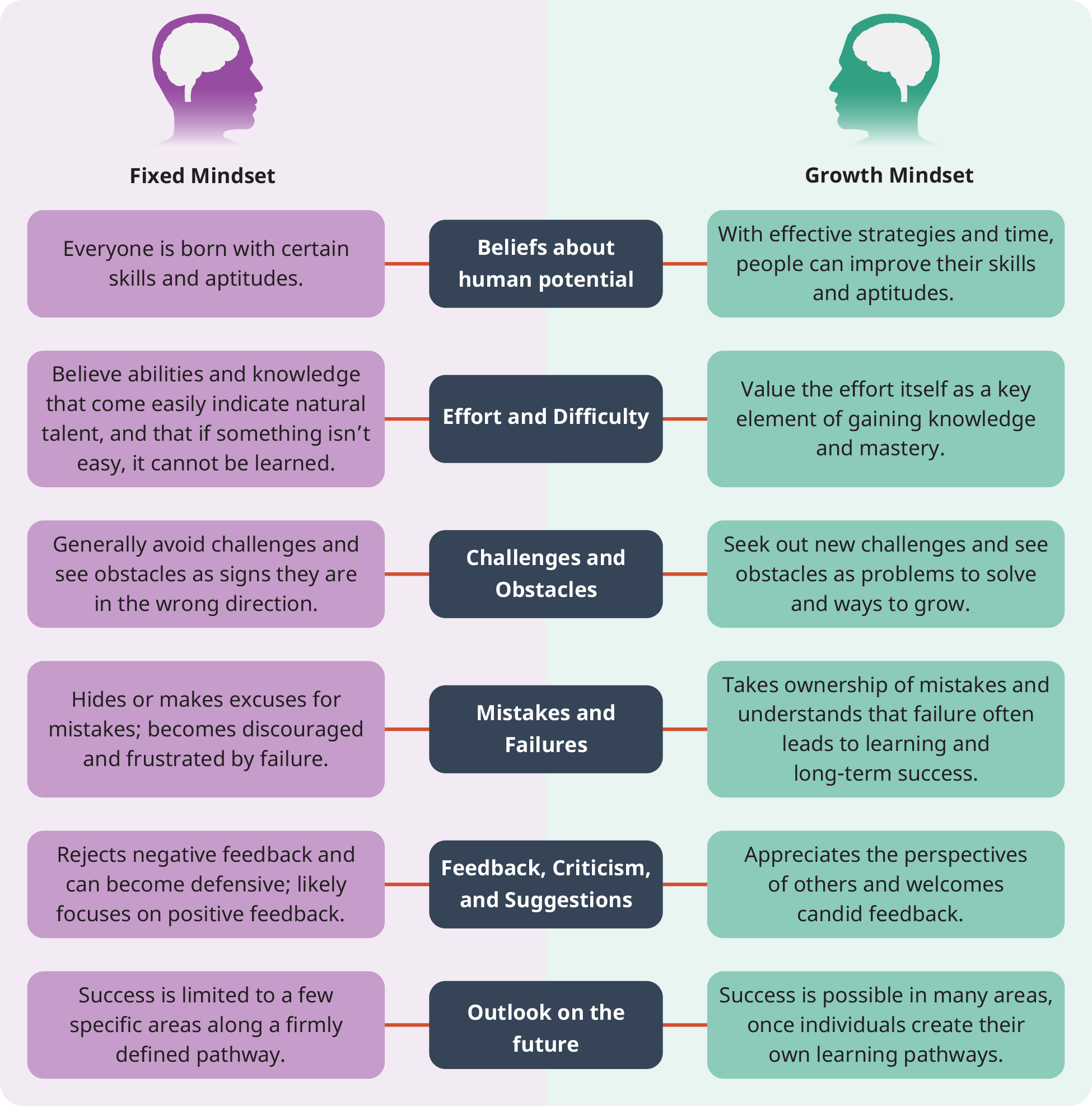

The research-based model of these two mindsets and their influence on learning was presented in 1988 by Carol Dweck.[7] In Dr. Dweck’s work, she determined that a student’s perception about their own learning accompanied by a broader goal of learning had a significant influence on their ability to overcome challenges and grow in knowledge and ability. This has become known as the Fixed vs. Growth Mindset model. In this model, the performance-goal-oriented student is represented by the fixed mindset, while the learning-goal-oriented student is represented by the growth mindset.

In the following graphic, based on Dr. Dweck’s research, you can see how many of the components associated with learning are impacted by these two mindsets.

Figure 5.11 The differences between fixed and growth mindset are clear when aligned to key elements of learning and personality. (Credit: Based on work by Dr. Carol Dweck)

The Growth Mindset and Lessons About Failing

Something you may have noticed is that a growth mindset would tend to give a learner grit and persistence. If you had learning as your major goal, you would normally keep trying to attain that goal even if it took you multiple attempts. Not only that, but if you learned a little bit more with each try you would see each attempt as a success, even if you had not achieved complete mastery of whatever it was you were working to learn.

With that in mind, it should come as no surprise that Dr. Dweck found that those people who believed their abilities could change through learning (growth vs. a fixed mindset) readily accepted learning challenges and persisted despite early failures.

Improving Your Ability to Learn

As strange as it may seem, research into fixed vs. growth mindsets has shown that if you believe you can learn something new, you greatly improve your ability to learn. At first, this may seem like the sort of feel-good advice we often encounter in social media posts or quotes that are intended to inspire or motivate us (e.g., believe in yourself!), but in looking at the differences outlined between a fixed and a growth mindset, you can see how each part of the growth mindset path would increase your probability of success when it came to learning.

Activity

Very few people have a strict fixed or growth mindset all of the time. Often we tend to lean one way or another in certain situations. For example, a person trying to improve their ability in a sport they enjoy may exhibit all of the growth mindset traits and characteristics, but they find themselves blocked in a fixed mindset when they try to learn something in another area like computer programming or arithmetic.

In this exercise, do a little self-analysis and think of some areas where you may find yourself hindered by a fixed mindset. Using the outline presented below, in the far right column, write down how you can change your own behavior for each of the parts of the learning process. What will you do to move from a fixed to a growth mindset? For example, say you were trying to learn to play a musical instrument. In the Challenges row, you might pursue a growth path by trying to play increasingly more difficult songs rather than sticking to the easy ones you have already mastered. In the Criticism row, you might take someone’s comment about a weakness in timing as a motivation for you to practice with a metronome. For Success of others you could take inspiration from a famous musician that is considered a master and study their techniques.

Whatever it is that you decide you want to use for your analysis, apply each of the Growth characteristics to determine a course of action to improve.

|

Parts of the learning process |

Growth characteristic |

What will you do to adopt a growth mindset? |

|

Challenges |

Embraces challenges |

|

|

Obstacles |

Persists despite setbacks |

|

|

Effort |

Sees effort as a path to success |

|

|

Criticism |

Learns from criticism |

|

|

Success of Others |

Finds learning and inspiration in the success of others |

|

Table 5.4

5.4 Learning Styles

Questions to consider:

- What are learning styles, and do they really work?

- How do I take advantage of learning styles in a way that works for me?

- How can I combine learning styles for better outcomes?

- What opportunities and resources are available for students with disabilities?

Several decades ago, a new way of thinking about learning became very prominent in education. It was based on the concept that each person has a preferred way to learn. It was thought that these preferences had to do with each person’s natural tendencies toward one of their senses. The idea was that learning might be easier if a student sought out content that was specifically oriented to their favored sense. For example, it was thought that a student who preferred to learn visually would respond better to pictures and diagrams.

Over the years there were many variations on the basic idea, but one of the most popular theories was known as the VAK model. VAK was an acronym for the three types of learning, each linked to one of the basic senses thought to be used by students: visual, aural, and kinesthetic. What follows is an outline of each of these and the preferred method.

Visual: The student prefers pictures, images, and the graphic display of information to learn. An example would be looking at an illustration that showed how to do something.

Aural: The student prefers sound as a way to learn. Examples would be listening to a lecture or a podcast.

Kinesthetic: The student prefers using their body, hands, and sense of touch. An example would be doing something physical, such as examining an object rather than reading about it or looking at an illustration.

The Truth about Learning Styles

In many ways these ideas about learning styles made some sense. Because of this, educators encouraged students to find out about their own learning styles. They developed tests and other techniques to help students determine which particular sense they preferred to use for learning, and in some cases learning materials were produced in multiple ways that focused on each of the different senses. That way, each individual learner could participate in learning activities that were tailored to their specific preferences.

While it initially seemed that dividing everyone by learning styles provided a leap forward in education, continued research began to show that the fixation on this new model might not have been as effective as it was once thought. In fact, in some cases, the way learning styles were actually being used created roadblocks to learning. This was because the popularization of this new idea brought on a rush to use learning styles in ways that failed to take into account several important aspects that are listed below:

A person does not always prefer the same learning style all the time or for each situation. For example, some learners might enjoy lectures during the day but prefer reading in the evenings. Or they may prefer looking at diagrams when learning about mechanics but prefer reading for history topics.

There are more preferences involved in learning than just the three that became popular. These other preferences can become nearly impossible to make use of within certain styles. For example, some prefer to learn in a more social environment that includes interaction with other learners. Reading can be difficult or restrictive as a group effort. Recognized learning styles beyond the original three include: social (preferring to learn as a part of group activity), solitary (preferring to learn alone or using self-study), or logical (preferring to use logic, reasoning, etc.).

Students that thought they were limited to a single preferred learning style found themselves convinced that they could not do as well with content that was presented in a way that differed from their style.[8] For example, a student that had identified as a visual learner might feel they were at a significant disadvantage when listening to a lecture. Sometimes they even believed they had an even greater impairment that prevented them from learning that way at all.

Some forms of learning are extremely difficult in activities delivered in one style or another. Subjects like computer programming would be almost impossible to learn using an aural learning style. And, while it is possible to read about a subject such as how to swing a bat or how to do a medical procedure, actually applying that knowledge in a learning environment is difficult if the subject is something that requires a physical skill.

Knowing and Taking Advantage of Learning Styles in a Way That Works for You

The problem with relying on learning styles comes from thinking that just one defines your needs. Coupling what you know about learning styles with what you know about UGT can make a difference in your own learning. Rather than being constrained by a single learning style, or limiting your activities to a certain kind of media, you may choose media that best fit your needs for what you are trying to learn at a particular time.

Following are a couple of ways you might combine your learning style preference with a given learning situation:

You are trying to learn how to build something but find the written instructions confusing so you watch a video online that shows someone building the same thing.

You have a long commute on the bus but reading while riding makes you dizzy. You choose an aural solution by listening to pre-recorded podcasts or a mobile device that reads your texts out loud.

These examples show that by recognizing and understanding what different learning styles have to offer, you can use the techniques that are best suited for you and that work best under the circumstances of the moment. You may also find yourself using two learning styles at the same time – as when you watch a live demonstration or video in which a person shows you how to do something while verbally explaining what you are being shown. This helps to reinforce the learning as it utilizes different aspects of your thinking. Using learning styles in an informed way can improve both the speed and the quality of your learning.

Get Connected

Finding content related to a subject or topic can be relatively easy, but you must use caution and rely on reputable sources. Relatively little of the material on the Web provides a way to ensure accuracy or balance.

Below are descriptions of common informational sites with varying degrees of reliability:

Khan Academy: This site is full of useful tutorials and videos on a wide range of subjects.

Wikipedia: Wikipedia is often frowned upon in some academic circles, because review of its content takes place after publication, potentially resulting in inaccurate or misleading information being available. But Wikipedia can provide a brief overview of a topic, and its lists of references is often quite extensive. You probably shouldn’t rely Wikipedia as your only source, but it can be useful.

Government website:. Most items that governments administer are referenced on informational websites. In the United States, these include educational statistics, economic data, health information, and many other topics.

When choosing alternate content, it is imperative to compare it to the content that is being provided to you as a part of your course. If the alternate content does not line up, you should view it with a healthy skepticism. In those cases, it is always a good idea to share the content with your instructor and ask their opinion.

Activity

In this activity you will try an experiment by combining learning styles to see if it is something that works for you. The experiment will test the example of combining reading/writing and aural learning styles for better memorization.

To begin, you will start with a short segment of numbers. You will read the numbers only one time without saying them aloud. When you are finished, wait 10 seconds and try to remember the numbers in sequence by writing them down.

67914528

After you have finished you will repeat the experiment with a new set of numbers, but this time you will read them aloud, wait 10 seconds, and then see how easy they are to remember. During this part of the experiment you are free to say the numbers in any way you like. For example, the number 8734 could be read as eight-seven-three-four, eighty-seven thirty-four, or any combination you would like.

10387264

Did you find that there was a difference in your ability to memorize a short sequence of numbers for 10 seconds? Even if you were able to remember both, was the example that combined learning styles easier? What about if you had to wait for a full minute before attempting to rewrite the numbers? Would that make a difference?

What about Students with Disabilities?

Students with disabilities are sometimes the most informed when it comes to making decisions about their own learning. They should understand that it is in their best interest to take ownership of their own approach to education, especially when it comes to leveraging resources and opportunities. In this section, you will learn about the laws that regulate education for students with disabilities as well as look at some resources that are available to them.

Just like anyone else, under the law, qualified students with disabilities are entitled to the same education colleges and universities provide to students without disabilities. Even though a particular disability may make attending college more difficult, awareness on the part of the government, learning institutions, and the students themselves has brought about a great deal of change over the years. Now, students with disabilities find that they have available appropriate student services, campus accessibility, and academic resources that can make school attendance and academic success possible.

Due to this increased support and advocacy, colleges have seen an increase of students with disabilities. According to the National Center for Education Statistics, in 2012, 11.1 percent of the total undergraduate population in the United States was made up of people with disabilities.[9]

The Legal Rights of Students with Disabilities

Section 504 of the Rehabilitation Act of 1973 protects students “with a physical or mental impairment which substantially limits one or more major life activities.”[10] Learning definitely falls within the definition of major life activities.

In addition to Section 504, another set of laws that greatly help learners with disabilities is the Americans with Disabilities Act of 1990 (also known as ADA). Both of these acts have been driving forces in making certain that students with disabilities have equal access to higher education, and they have been instrumental in helping educators looking for new ways and resources to provide services that do just that.

What follows is a list of services that schools commonly provide to help students with disabilities. These are often referred to as ADA accommodations and are named after the American with Disabilities Act:

- Recordings of class lectures or lecture transcription by in-class note takers

- Text readers or other technologies that can deliver content in another format

- Test or assessment accommodations

- Interpreter services and Braille transcriptions

- Physical access accommodations

- Accommodations of time and due dates

Most colleges will have policies and staff that are designated to help arrange for these types of accommodations. They are often found within the Department of Student Services or in related departments within your college campus. If you are a student with disabilities protected under these acts, it is in your best interest to contact the person responsible for ADA accommodations at your school. Even if you decide that you do not need accommodations, it is a good idea to find out about any services and policies the school has in place.

Organizations

In addition to the accommodations that schools commonly provide, there are also a number of national and local organizations that can provide assistance and advice when it comes to being a student with a disability. If you fit into this category, it is recommended that you make contact with one or more of these organizations in order to find out how they can help. These can be tremendously beneficial resources that offer everything from information and support to simple social connections that can make pursuing a formal education easier.

5.5 Personality Types and Learning

Questions to consider:

- Is there any connection between personality types and learning?

- Can the Myers-Briggs test be used to identify personality traits and learning styles?

- Is there a real correlation between personality styles and learning?

- What is the impact on learning with work that you enjoy?

Much like learning styles, there have been a number of theories surrounding the idea that different personality types may prefer different kinds of learning. Again, this builds on the original learning style concept that people may have a single preference toward how they learn, and then adds to it that certain personality traits may determine which learning style a person prefers.

Since it has already been determined that learning styles are more effective when selected for the subject being learned rather than the sensory preference of the learner, it might seem foolish to revisit another learning style theory. But, in this case, understanding how personality traits and learning styles are categorized can be useful in making decisions and choices for your own learning activities. In other words, we won’t dismiss the theory out of hand without first seeing if there is anything useful in it.

One part of this theory that can be useful is the identification of personality traits that affect your motivation, emotions, and interests toward learning. You have already read a great deal about how these internal characteristics can influence your learning. What knowing about personality traits and learning can do for you is to help you be aware and informed about how these affect you so you can deal with them directly.

Myers-Briggs: Identifying Personality Traits and Styles

The Myers-Briggs system is one of the most popular personality tests, and it is relatively well known. It has seen a great deal of use in the business world with testing seminars and presentations on group dynamics. In fact, it is so popular that you may already be familiar with it and may have taken a test yourself to find out which of the 16 personality types you most favor.

The basic concept of Myers-Briggs is that there are four main traits. These traits are represented by two opposites, seen in the table below.

|

Extroverted (E) |

vs. |

Introverted (I) |

|

Intuition (N) |

vs. |

Sensing (S) |

|

Feeling (F) |

vs. |

Thinking (T) |

|

Judging (J) |

vs. |

Perceiving (P) |

Table 5.5

It is thought that people generally exhibit one trait or the other in each of these categories, or that they fall along a spectrum between the two opposites. For example, an individual might exhibit both Feeling and Thinking personality traits, but they will favor one more than the other.

Also note that with each of these traits there is a letter in parentheses. The letter is used to represent the specific traits when they are combined to define a personality type (e.g., Extrovert is E and Introvert is I, Intuition is N, etc.). To better understand these, each is briefly explained.

Extroverted (E) vs. Introverted (I): In the Myers-Briggs system, the traits of Extroverted and Introverted are somewhat different from the more common interpretations of the two words. The definition is more about an individual’s attitude, interests, and motivation. The extrovert is primarily motivated by the outside world and social interaction, while the introvert is often more motivated by things that are internal to them—things like their own interests.

Intuition (N) vs. Sensing (S): This personality trait is classified as a preference toward one way of perceiving or another. It is concerned with how people tend to arrive at conclusions. A person on the intuitive end of the spectrum often perceives things in broader categories. A part of their process for “knowing things” is internal and is often described as having a hunch or a gut feeling. This is opposed to the preferred method of a sensing person, who often looks to direct observation as a means of perception. They prefer to arrive at a conclusion by details and facts, or by testing something with their senses.

Feeling (F) vs. Thinking (T): This trait is considered a decision-making process over the information gathered through the perception (N versus S). People that find themselves more on the Feeling end of the spectrum tend to respond based on their feelings and empathy. Examples of this would be conclusions about what is good versus bad or right versus wrong based on how they feel things should be. The Thinking person, on the other hand, arrives at opinions based on reason and logic. For them, feeling has little to do with it.

Judging (J) vs. Perceiving (P): This category can be thought of as a personal preference for using either the Feeling versus Thinking (decision-making) or the Intuition versus Sensing (perceiving) when forming opinions about the outside world. A person that leans toward the Judging side of the spectrum approaches things in a structured way—usually using Sensing and Thinking traits. The Perceiving person often thinks of structure as somewhat inhibiting. They tend to make more use of Intuition and Feeling in their approach to life.

The Impact of Personality Styles on Learning

To find out their own personality traits and learning styles, a person takes an approved Myers-Briggs test, which consists of a series of questions that help pinpoint their preferences. These preferences are then arranged in order to build a profile using each of the four categories.

For example, a person that answered questions in a way that favored Extroverted tendencies along with a preference toward Sensing, Thinking, and Judging would be designated as ESTJ personality type. Another person that tended more toward answers that aligned with Intuitive traits than Sensing traits would fall into the ENTJ category.

|

ESTJ |

ISTJ |

ENTJ |

INTJ |

|

ESTP |

ISTP |

ENTP |

INTP |

|

ESFJ |

ISFJ |

ENFJ |

INFJ |

|

ESFP |

ISFP |

ENFP |

INFP |

Table 5.6 Personality Types

As with other learning style models, Myers-Briggs has received a good deal of criticism based on the artificial restrictions and impairments it tends to suggest. Additionally, the claim that each person has a permanent and unwavering preference towards personality traits and learning styles has not turned out to be as concrete as it was once thought. This has been demonstrated by people taking tests like the Myers-Briggs a few weeks apart and getting different results based on their personal preferences at that time.

What this means is that, just as with the VAK and other learning style models, you should not constrain your own learning activities based on a predetermined model. Neither should you think of yourself as being limited to one set of preferences. Instead, different types of learning and different preferences can better fit your needs at different times. This and how to best apply the idea of personality types influencing learning styles is explained in the next section.

How to Use Personality Type Learning Styles

To recap, personality tests such as the Myers-Briggs can provide a great deal of insight into personal choices toward learning. Unfortunately, many people interpret them as being something that defines them as both a person and a learner. They tell themselves things like “I am an ESTJ, so I am only at my best when I learn a certain way” or “I rely on intuition, so a science course is not for me!” They limit themselves instead of understanding that while they may have particular preferences under a given situation, all of the different categories are open to them and can be put to good use.

What is important to know is that these sorts of models can serve you better as a way to think about learning. They can help you make decisions about how you will go about learning in a way that best suits your needs and goals for that particular task. As an example of how to do this, what follows are several different approaches to learning about the play Julius Caesar by William Shakespeare. In each case, Myers-Briggs categories are used to define what sort of activities would help you meet your desired learning goals.

Your assignment is to read Julius Caesar as a work of English literature. Your learning goal is not just to read the play, but to be able to compare it to other, more modern works of literature. To do that, it would be beneficial to use a more introverted approach so that you can think about the influences that may have affected each author. You might also want to focus on a thinking learning style when examining and comparing the use of words and language in the 17th-century piece to more modern writing styles.

Your use of learning style approaches would be very different if you were assigned to actually perform a scene from Julius Caesar as a part of a class. In this case, it would be better for you to rely on an extroverted attitude since you will be more concerned with audience reaction than your own inner thoughts about the work. And since one of your goals would be to create a believable character for the audience, you would want to base decisions on the gestures you might make during the performance through feeling so that you have empathy with the character and are convincing in your portrayal.

A third, completely different assignment, such as examining the play Julius Caesar as a political commentary on English society during the reign of Queen Elizabeth, would have very different goals and therefore should be approached using different learning styles. In this example, you might want to begin by using a sensing approach to gather facts about what was happening politically in that time period and then switch to intuition for insight into the motivations of Shakespeare and the attitudes of his audience in England at that time.

As you can see in the examples above, the choices about each of the different approaches can be entirely dictated by what you will be doing with the learning. Because of this, being aware of the personality type learning styles you have available to you can make a tremendous difference in both how you go about it and your success.

Analysis Question

To find out more about personality types and learning styles, you can take an online personality test to experience it yourself. Several companies charge for this service, but there are a few that offer tests online for free. Click here for one such free online personality test.

Again, keep in mind that your results can change under different circumstances, but doing it for the first time will give you a place to start.

Afterwards you can click here to read more about the connections between personality and learning styles. There you can look up the results from your personality test and see how much you think it aligns with your learning style preferences. Again, this exercise is not to determine your ultimate learning style, but it is to give you a deeper understanding of what is behind the concept of connecting personality types to learning.

The Impact of Work You Enjoy

For a final word on personality types and learning styles, there is no denying that there are going to be different approaches you enjoy more than others. While you do have the ability to use each of the different approaches to meet the goals of your learning activities, some will come more easily for you in certain situations and some will be more pleasurable. As most people do, you will probably find that your work is actually better when you are doing things you like to do. Because of this, it is to your advantage to recognize your preferred methods of learning and to make use of them whenever possible. As discussed elsewhere in this book, in college you will often have opportunities to make decisions about the assignments you complete. In many instances, your instructor may allow for some creativity in what you do and in the finished product. When those opportunities arise, you have everything to gain by taking a path that will allow you to employ preferences you enjoy most. An example of this might be an assignment that requires you to give a presentation on a novel you read for class. In such a case, you might have the freedom to focus your presentation on something that interests you more and better aligns with how you like to learn. It might be more enjoyable for you to present a study on each of the characters in the book and how they relate to each other, or you might be more interested in doing a presentation on the historical accuracy of the book and the background research the author put into writing it.

Whatever the case, discuss your ideas with your instructor to make certain they will both meet the criteria of the assignment and fulfill the learning goals of the activity. There is a great potential for benefit in talking with your instructors when you have ideas about how you can personalize assignments or explore areas of the subject that interest you. In fact, it is a great practice to ask your instructors for guidance and recommendations and, above all, to demonstrate to them that you are taking a direct interest in your own learning. There is never any downside to talking with your instructors about your learning.

5.6 Applying What You Know about Learning

Questions to consider:

- How can I apply what I now know to learning?

- How can I make decisions about my own learning?

- Will doing so be different from what I have experienced before?

Another useful part of being an informed learner is recognizing that as a college student you will have many choices when it comes to learning. Looking back at the Uses and Gratification model, you’ll discover that your motivations as well as your choices in how you interact with learning activities can make a significant difference in not only what you learn, but how you learn. By being aware of a few learning theories, students can take initiative and tailor their own learning so that it best benefits them and meets their main needs.

Student Profile

“My seating choice significantly affects my learning. Sitting at a desk where the professor’s voice can be heard clearly helps me better understand the subject; and ensuring I have a clear view helps me take notes. Therefore, sitting in the front of the classroom should be a “go to” strategy while attending college. It will keep you focused and attentive throughout the lecture. Also, sitting towards the front of the classroom limits the tendency to be on [or] check my phone.” —Luis Angel Ochoa, Westchester Community College

Making Decisions about Your Own Learning

As a learner, the kinds of materials, study activities, and assignments that work best for you will derive from your own experiences and needs (needs that are both short-term as well as those that fulfill long-term goals). In order to make your learning better suited to meet these needs, you can use the knowledge you have gained about UGT and other learning theories to make decisions concerning your own learning. These decisions can include personal choices in learning materials, how and when you study, and most importantly, taking ownership of your learning activities as an active participant and decision maker. In fact, one of the main principles emphasized in this chapter is that students not only benefit from being involved in planning their instruction, but learners also gain by continually evaluating the actual success of that instruction. In other words: Does this work for me? Am I learning what I need to by doing it this way?