7.1 Nonverbal Communication

Nonverbal communication is defined as communication that is produced by some means other than words (eye contact, body language, or vocal cues, for example).1 Imagine the lack of a variety of emotional facial expressions if everyone’s face was frozen. The world would be a much less interesting place, and it would be more challenging to stimulate accurate meaning in the minds of others; thus, we will begin this chapter by discussing the importance of nonverbal communication.

Importance of Nonverbal Communication in Interaction

The Role of Nonverbal in Everyday Life

We communicate nonverbally constantly. It’s the primary way that we communicate with other people. In this section, we’re going to explore the role that nonverbal communication plays in our day-to-day lives.

Nonverbal has Communicative Value

The meaning associated with nonverbal communication in any given interaction cannot be underestimated. In this chapter, you will learn about the many types of nonverbal communication present in the interaction. For example, if you are having a conversation with your friend who just broke up with her girlfriend, you will use more than the words, “I just broke up with my girlfriend” to understand how to communicate with your friend. Your friend’s facial expression, way of standing, rate of speech, tone of voice, and general appearance, just to name a few, will indicate to you how you should respond. If she is sobbing, gasping for air, hunched over, and appears emotionally pained, you might attempt to comfort her. If she says, “I just broke up with my girlfriend” and sighs while placing her hand over her heart, she might appear relieved. Your response might be, “it seems like you may be a little relieved. Were things not going well?”

Thus, nonverbal communication plays a tremendous role in successfully engaging in interactions. The successful use of nonverbal communication requires an awareness of the value of nonverbal communication and the belief that it is valuable. When individuals are unaware of the importance of nonverbal communication, they may be overlooking crucial interactional information. For example, one of the authors of this textbook was once meeting with a colleague who was repeatedly sighing during a meeting. Later, when she and her colleague were discussing the meeting, he said, “Didn’t you notice that I was sighing?” She told him she did notice that he was sighing, but she was unsure why. We will discuss this further in the ambiguity of nonverbal communication. In this example, the author’s colleague was aware of the importance of nonverbal communication and attempted to use it deliberately.

In addition to awareness, individuals must believe that nonverbal communication is valuable. If your parent/guardian ever said to you, “it wasn’t what you said, it was how you said it,” then your parent/guardian was demonstrating a belief that nonverbal communication is essential. An individual may acknowledge that nonverbal communication exists but may discount its value. For example, one of the authors had a recurring argument with the author’s spouse, who would sigh or roll her eyes as a response in interaction. The author would ask the spouse what it meant, and the spouse would inevitably say, “I can sigh or roll my eyes without it meaning anything.” This is not an uncommon response, but the authors of this text hope to dispel this perception.

For a better understanding of the value of communication, Google “value of communication.” Your search will return over a billion links. While it is not possible to review all of the search results, read through a few of the articles. For this exercise we found titles like “The Value of Effective Communication in the Workplace”a and “Why Communication Is Today’s Most Important Skill.”2 In fact, we found almost 300,000 articles with the phrase “value of communication.” These news articles tell readers that effective communication secures customer, creates bonds between employees, and increases revenues.

Nonverbal Used for Relational Purposes

Nonverbal communication is an essential element in relating to others. Nonverbal communication is often the very first way in which we invite a relationship with another, or, at the very least, invite communication. To communicate with another, we must make eye contact with a few exceptions. Thus, relationships begin with nonverbal communication. Also, consider how humans relate to others through touch, scent, hand gestures, physical appearance, and more.

Humans often use nonverbal communication to relay to others an interest in continuing a conversation or leaving a conversation. For example, you may run into a colleague and strike up a spontaneous conversation in the hall. The conversation is enjoyable, and you each relate to the other that you are enjoying conversing about work. Your colleague may recognize that he needs to get to a meeting and relates this information to you by looking at his watch, beginning to back away, or looking at the door he needs to enter.

Another way in which we relate to others via nonverbal communication is through the communication of emotion. Through a myriad of nonverbal behaviors, we can communicate emotions such as joy, happiness, and sadness. The nonverbal expression of emotion allows others to know how to communicate with us.

Nonverbal is Ambiguous

A particularly challenging aspect of nonverbal communication is the fact that it is ambiguous. In the seventies, nonverbal communication as a topic was trendy. Some were under the impression that we could use nonverbal communication to “read others like a book.” One of the authors remembers her cousin’s wife telling her that she shouldn’t cross her arms because it signaled to others that she was closed off. It would be wonderful if crossing one’s arms signaled one meaning, but think about the many meanings of crossing one’s arms. An individual may have crossed arms because the individual is cold, upset, sad, or angry. It is impossible to know unless a conversation is paired with nonverbal behavior.

Another great example of ambiguous nonverbal behavior is flirting! Consider some very stereotypical behavior of flirting (e.g., smiling, laughing, a light touch on the arm, or prolonged eye contact). Each of these behaviors signals interest to others. The question is whether an individual engaging in these behaviors is indicating romantic interest or a desire for platonic friendship…have you ever walked away from a situation and explained a person’s behavior to another friend to determine whether you were being flirted with? If so, you have undoubtedly experienced the ambiguity of nonverbal communication.

Nonverbal is Culturally Based

Just as we have discussed that it is beneficial to recognize the value of nonverbal communication, we must also acknowledge that nonverbal communication is culturally based. Successful interactions with individuals from other cultures are partially based on the ability to adapt to or understand the nonverbal behaviors associated with different cultures. There are two aspects to understanding that nonverbal communication is culturally based. The first aspect is recognizing that even if we do not know the appropriate nonverbal communication with someone from another culture, then we must at least acknowledge that there is a need to be flexible, not react, and ask questions. The second aspect is recognizing that there are specific aspects of nonverbal communication that differ depending on the culture. When entering a new culture, we must learn the rules of the culture.

Regarding recognizing differences, you may encounter someone from a culture that communicates very differently from you and perhaps in an unexpected way. For example, one of the author’s brothers, Patrick, was working in Afghanistan as a contractor on a military base. He was working with a man from Africa. During their first conversation, he held Patrick’s hand. Patrick later told his sister, the author, this story and said he wasn’t sure how to respond, so he “just rolled with it.” Patrick’s response allowed for the most flexibility in the situation and the best chance of moving forward productively. Imagine if he had withdrawn his hand quickly with a surprised look on his face. The outcome of the interaction would have been very different.

Patrick’s response also exemplifies the second aspect of understanding that nonverbal communication is culturally based. Patrick was hired by a contractor to work on the military base in Afghanistan. The contracting firm could have trained Patrick and his coworkers about communicating with the various cultures they would encounter on the base. For example, many people from the Philippines were working on the base. It would have been helpful for the contractors to explain that there may be differences in spatial distance and touch when communicating with other males from the Philippines. Researching and understanding the nonverbal communication of different countries before entering the country can often mean a smoother entry phase, whether conducting business or simply visiting.

Attribution Error

A final area to address before examining specific aspects of nonverbal communication is “attribution error.” Attribution error is defined as the tendency to explain another individual’s behavior in relation to the individual’s internal tendencies rather than an external factor.3 For example, if a friend is late, we might attribute this failure to be on time as the friend being irresponsible rather than running through a list of external factors that may have influenced the friend’s ability to be on time such as an emergency, traffic, read the time wrong, etc. It is easy to make an error when trying to attribute meaning to the behaviors of others, and nonverbal communication is particularly vulnerable to attribution error.

On Saturday, September 8, 2018, Serena Williams may have been a victim of an umpire’s attribution error on the part of the judge. Let’s just say Serena did suffer as a result of attribution error. The judge spotted Serena Williams’ coach gesturing in the audience and assumed that the gesture was explicitly directed toward Serena as a means to coach her. Her coach later acknowledged that he was “coaching” via nonverbal signals, but Serena was not looking at him, nor was she intended to be a recipient. Her coach indicated that all coaches gesture while sitting in the stands as though they are coaching a practice and that it’s a habit and not an other-oriented communication behavior. This is a perfect example of attribution error. The judge attributed the coaches’ gesture to the coach intending to communicate rather than the gesture merely being due to habit. The judge’s attribution error may have cost Serena William’s comeback match. While the stakes may not be so high in day-to-day interaction, attribution error can create relational strife and general misunderstandings that can be avoided if we recognize that it is necessary to understand the intention behind a specific nonverbal behavior.

Omnipresent

According to Dictionary.com, omnipresent is indicative of being everywhere at the same time. Nonverbal communication is always present. Silence is an excellent example of nonverbal communication being omnipresent. Have you ever given someone the “silent treatment?” If so, you understand that by remaining silent, you are trying to convey some meaning, such as “You hurt me” or “I’m really upset with you.” Thus, silence makes nonverbal communication omnipresent.

Another way of considering the omnipresence of nonverbal communication is to consider the way we walk, posture, engage in facial expression, eye contact, lack of eye contact, gestures, etc. When sitting alone in the library working, your posture may be communicating something to others. If you need to focus and don’t want to invite communication, you may keep your head down and avoid eye contact. Suppose you are walking across campus at a brisk pace. What might your pace be communicating?

When discussing the omnipresence of nonverbal communication, it is necessary to discuss Paul Watzlawick’s assertion that humans cannot, not communicate. This assertion is the first axiom of his interactional view of communication. According to Watzlawick, humans are always communicating. As discussed in the “silent treatment” example and the posture and walking example, communication is found in everyday behaviors that are common to all humans. We might conclude that humans cannot escape communicating meaning.

Can Form Universal Language

When discussing whether nonverbal communication is a universal language, caution must be used. We must remember that understanding the context in which nonverbal communication is used is almost always necessary to understand the meaning of nonverbal communication. However, there are exceptions concerning what Paul Ekman calls “basic emotions.” These will be discussed a bit later in the chapter.

Can Lead to Misunderstandings

Comedian Samuel J. Comroe has tremendous expertise in explaining how nonverbal communication can be misunderstood. Comroe’s comedic routines focus on how Tourette’s syndrome affects his daily living. Tourette’s syndrome can change individual behavior, from uncontrolled body movements to uncontrolled vocalizations. Comroe often appears to be winking when he is not. He explains how his “wink” can cause others to believe he is joking when he isn’t. He also tells the story of how he met his wife in high school. During a skit, he played a criminal and she played a police officer. She told him to “freeze,” and he continued to move (due to Tourette’s). She misunderstood his movement to mean he was being defiant and thus “took him down.” You can watch Comroe’s routine here.

Although nonverbal misunderstandings can be humorous, these misunderstandings can affect interpersonal as well as professional relationships. One of the authors once went on an important job interview for a job she was not offered. She asked the interviewer for feedback, and he said, “your answers sounded canned.” The author did not think to do so in the moment, but what she should have said is that she may have sounded canned because she frequently thinks about work, her work philosophy, and how she approaches work. Thus, her tone may have been more indicative of simply knowing how she feels rather than “canned.”

As you continue to learn about nonverbal communication, consider how you come to understand nonverbal communication in interactions. Sometimes, the meaning of nonverbal communication can be fairly obvious. Most of the time a head nod in conversation means something positive such as agreement, “yes,” keep talking, etc. At other times, the meaning of nonverbal communication isn’t clear. Have you ever asked a friend, “did she sound rude to you” about a customer service representative? If so, you are familiar with the ambiguity of nonverbal communication.

Usually Trusted

Despite the pitfalls of nonverbal communication, individuals typically rely on nonverbal communication to understand the meaning in interactions. Communication scholars agree that the majority of meaning in any interaction is attributable to nonverbal communication. It isn’t necessarily true, but we are taught from a very early age that lack of eye contact is indicative of lying. We have learned through research that this “myth” is not necessarily true; this myth does tell a story about how our culture views nonverbal communication. That view is simply that nonverbal communication is important and that it has meaning.

Another excellent example of nonverbal communication being trusted may be related to a scenario many have experienced. At times, children, adolescents, and teenagers will be required by their parents/guardians to say, “I’m sorry” to a sibling or the parent/guardian. Alternatively, you may have said “yes” to your parents/guardians, but your parent/guardian doesn’t believe you. A parent/guardian might say in either of these scenarios, “it wasn’t what you said, it was how you said it.” Thus, we find yet another example of nonverbal communication being the “go-to” for meaning in an interaction.

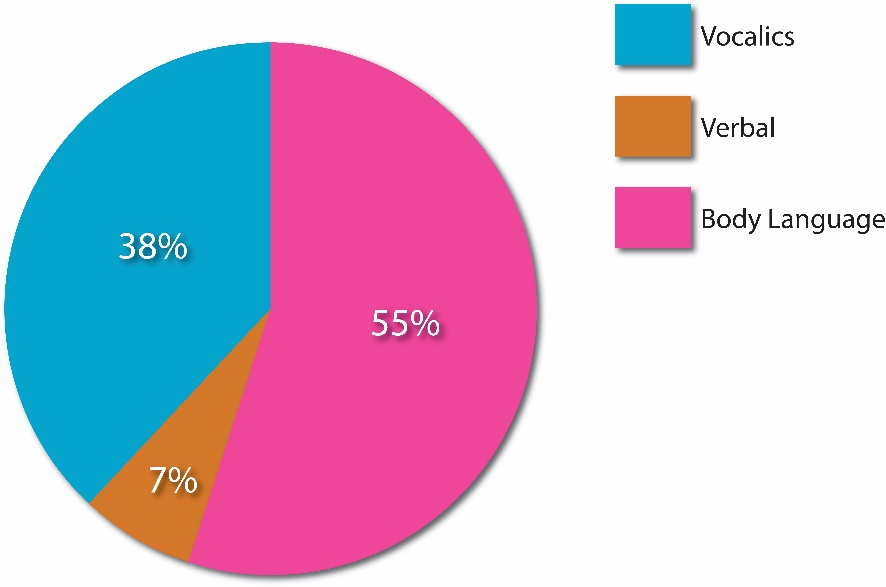

According to research, as much as 93% of meaning in any interaction is attributable to nonverbal communication. Albert Mehrabian asserts that this 93% of meaning can be broken into three parts.4

Figure 7.1

Mehrabian’s Explanation of Message Meaning

Mehrabian’s work is widely reported and accepted. Other researchers Birdwhistell and Philpott say that meaning attributed to nonverbal communication in interactions ranges from 60 to 70%.5,6 Regardless of the actual percentage, it is worth noting that the majority of meaning in interaction is deduced from nonverbal communication.

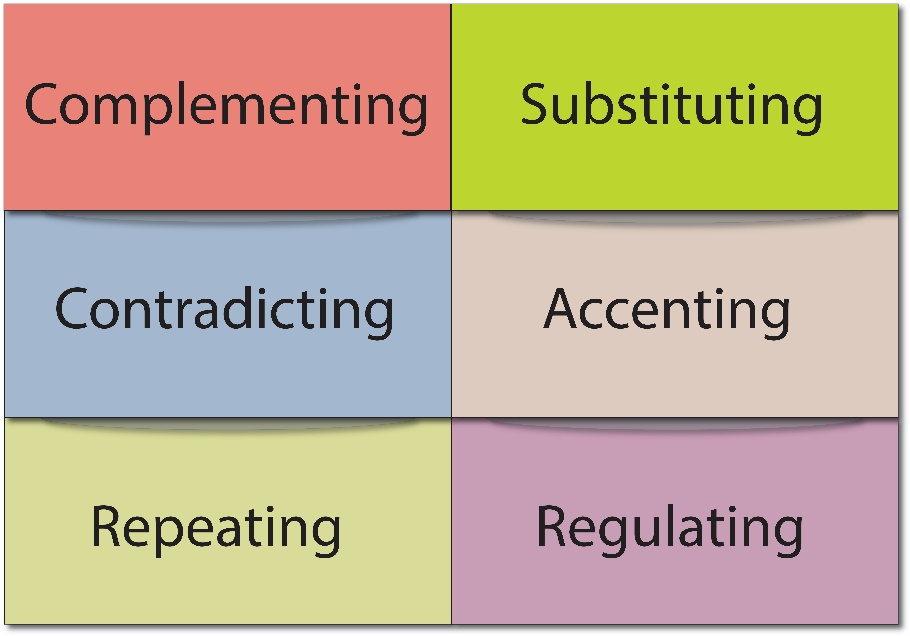

The Six Functions of Nonverbal Communication

As we have established, nonverbal communication plays an important role in communicating successfully and effectively. Because nonverbal communication plays a significant role in interactions, nonverbal communication was studied heavily in the early days of studying communication. These studies resulted in the discovery of multiple utilitarian functions of nonverbal communication.

Figure 7.2

Six Functions of Nonverbal Communication

Complementing

Complementing is defined as nonverbal behavior that is used in combination with the verbal portion of the message to emphasize the meaning of the entire message. An excellent example of complementing behavior is when a child is exclaiming, “I’m so excited” while jumping up and down. The child’s body is further emphasizing the meaning of “I’m so excited.”

Contradicting

At times, an individual’s nonverbal communication contradicts verbal communication. Recently, when visiting an aunt’s house, one of the author’s folded her arms. She asked the author if she was cold and if she needed to turn up the air conditioning. The author said no because she was trying to be polite, but her aunt did not believe her. The author’s nonverbal communication gave away her actual discomfort! In this case, the nonverbal communication was truly more meaningful than verbal communication.

Consider a situation where a friend says, “The concert was amazing,” but the friend’s voice is monotone. A response might be, “oh, you sound real enthused.” Communication scholars refer to this as “contradicting” verbal and nonverbal behavior. When contradicting occurs, the verbal and nonverbal messages are incongruent. This incongruence heightens our awareness, and we tend to believe the nonverbal communication over verbal communication.

Accenting

Accenting is a form of nonverbal communication that emphasizes a word or a part of a message. The word or part of the message accented might change the meaning of the message. Accenting can be accomplished through multiple types of nonverbal behaviors. Gestures paired with a word can provide emphasis, such as when an individual says, “no (slams hand on table), you don’t understand me.” By slamming the hand on a table while saying “no,” the source draws attention to the word. Words or phrases can also be emphasized via pauses. Speakers will often pause before saying something important. Your professors likely pause just before relaying information that is important to the course content.

Repeating

Nonverbal communication that repeats the meaning of verbal communication assists the receiver by reinforcing the words of the sender. Nonverbal communication that repeats verbal communication may stand alone, but when paired with verbal communication, it servers to repeat the message. For example, nodding one’s head while saying “yes” serves to reinforce the meaning of the word “yes,” and the word “yes” reinforces the head nod.

Regulating

Regulating the flow of communication is often accomplished through nonverbal behavior communication. Paul Ekman and Wallace Friesen state that regulators are “acts which maintain and regulate the back-and-forth nature of speaking and listening between two or more interactions” (1969, p. 82). You may notice your friends nodding their heads when you are speaking. Nodding one’s head is a primary means of regulating communication. Other behaviors that regulate conversational flow are eye contact, moving or leaning forward, changing posture, and eyebrow raises, to name a few. You may also have noticed several nonverbal behaviors people engage in when trying to exit a conversation. These behaviors include stepping away from the speaker, checking one’s watch/phone for the time, or packing up belongings. These are referred to as leave-taking behaviors. Without the regulating function of nonverbal behaviors, it would be necessary to interrupt conversational content to insert phrases such as “I have to leave.” However, when interactants fail to recognize regulating behavior, verbal communication will be used instead.

Substituting

At times, nonverbal behavior serves to replace verbal communication altogether. Substituting nonverbal behaviors must be understood within a context more often than not. For example, a friend may ask you what time it is, and you may shrug your shoulders to indicate you don’t know. At other times, your friend may ask whether you want pizza or sushi for dinner, and you may shrug your shoulders to indicate you don’t care or have no preference.

Emblems are a specific type of substituting nonverbal behavior that have direct verbal translation. Emblems may generally be understood outside of the context in which they are used. Some highly recognizable emblems in the U.S. culture are the peace sign and the okay sign. Emblems are a generally understood concept and have made their way into popular culture. The term “emblem” may not be applied within popular culture. In the popular television show, Friends, the main characters Ross and Monica are siblings. Ross and Monica are forbidden to “flip the bird” to each other, so they make up their own “emblem,” which involves holding one’s palms upward in a fist and bumping the outside of the palm’s together. Whether flipping the bird in the traditional manner or doing so Ross and Monica style, each of these represents an emblem that does not require context for accurate interpretation. Emblems will be discussed in greater depth later in the chapter.

Key Takeaways

- Nonverbal cues help the receiver decode verbal messages.

- Each function of nonverbal communication is distinct.

- The functions of nonverbal communication are evident in everyday interactions.

Categories of Nonverbal Communication

In addition to the functions of nonverbal communication, there are categories of nonverbal communication. This chapter will address several categories of nonverbal communication that are of particular importance in interpersonal relationships. These categories include haptics (touch), vocalics (voice), kinesics (body movement and gestures), oculesics/facial expressions (eye and face behavior), and physical appearance. Each of these categories influences interpersonal communication and may have an impact on the success of interpersonal interactions.

Haptics

Haptics is the study of touch as a form of nonverbal communication. Touch is used in many ways in our daily lives, such as greeting, comfort, affection, task accomplishment, and control. You may have engaged in a few or all of these behaviors today. If you shook hands with someone, hugged a friend, kissed your romantic partner, then you used touch to greet and give affection. If you visited a salon to have your hair cut, then you were touched with the purpose of task accomplishment. You may have encountered a friend who was upset and patted the friend to ease the pain and provide comfort. Finally, you may recall your parents or guardians putting an arm around your shoulder to help you walk faster if there was a need to hurry you along. In this case, your parent/guardian was using touch for control.

Several factors impact how touch is perceived. These factors are duration, frequency, and intensity. Duration is how long touch endures. Frequency is how often touch is used, and intensity is the amount of pressure applied. These factors influence how individuals are evaluated in social interactions. For example, researchers state, “a handshake preceding social interactions positively influenced the way individuals evaluated the social interaction partners and their interest in further interactions while reversing the impact of negative impressions.”7 This research demonstrates that individuals must understand when it is appropriate to shake hands and that there are negative consequences for failing to do so. Importantly, an appropriately timed handshake can erase the negative effects of any mistakes one might make in an initial interaction!

Touch is a form of communication that can be used to initiate, regulate, and maintain relationships. It is a very powerful form of communication that can be used to communicate messages ranging from comfort to power. Duration, frequency, and intensity of touch can be used to convey liking, attraction, or dominance. Touch can be helpful or harmful and must be used appropriately to have effective relationships with family, friends, and romantic partners. Consider that inappropriate touch can convey romantic intentions where no romance exists. Conversely, fear can be instilled through touch. Touch is a powerful interpersonal tool along with voice and body movement.

It’s also essential to understand the importance of touch on someone’s psychological wellbeing. Narissra Punyanunt-Carter and Jason Wrench created the touch deprivation scale to examine the lack of haptic communication in an individual’s life.8

Figure 7.2

Touch Deprivation Scale

Read the following questions and select the answer that corresponds with how you perceive physical contact with other people. Do not be concerned if some of the items appear similar. Please use the scale below to rate the degree to which each statement applies to you:

| Strongly Disagree | Disagree | Neutral | Agree | Strongly Agree |

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

_____1. I do not receive as much touch in my life as normal people.

_____2. I receive a normal, healthy amount of touch from people.

_____3. Human touch is not a daily occurrence in my life.

_____4. Touch from other people is a very common and natural part of my daily life.

_____5. I often go for days without being touched by someone.

_____6. I often feel like I’m untouchable because of the lack of touch from others in my life.

_____7. I receive a variety of forms of touch from a variety of different people.

_____8. I can go long periods of time without being touched by another person.

_____9. There are days when I would do anything just to be touched by someone.

_____10. I have longed for the touch of another person, any person.

_____11. Some days I long to be held, but have no one to hold me.

_____12. I often wish I could get more hugs from others.

_____13. I’ve engaged in sexual behaviors for the pure purpose of being touched by someone.

_____14. I would never engage in sex with someone, just to be touched.

SCORING: To compute your scores follow the instructions below:

Absence of Touch

Step One: Add scores for items 1, 3, 5, 6, & 8_____

Step Two: Add scores for items 2, 4, & 7_____

Step Three: Add 18 to Step One._____

Step Four: Subtract the score for Step two from the score for Step Three._____

Longing for Touch

Step One: Add scores for items 9, 10, 11, & 12_____

Sex for Touch

Step One: Add scores for item 13_____

Step Two: Add scores for item 14_____

Step Three: Add 6 to Step One._____

Step Four: Subtract the score for Step Two from the score for Step Three._____

Interpreting Your Score:

For absence of touch, scores should be between 7 and 35. If your score is above 17, you are considered to have an absence of touch. If your score is below 16, then touch is a normal part of your daily life.

For longing for touch, scores should be between 4 and 20. If your score is above 10, you are considered to have a longing for touch in your life. If your score is below 9, then touch is a normal part of your daily life.

For sex for touch, scores should be between 2 and 10. If your score is above 5, you have probably engaged in sexual intimacy as a way of receiving touch in your life. If your score is below 5, then you probably have not in sexual intimacy as a way of receiving touch in your life.

Source:

Punyanunt-Carter, N. M., & Wrench, J. S. (2009). Development and validity testing of a measure of touch deprivation. Human Communication, 12, 67-76.

As you can see, Punyanunt-Carter and Wrench found that there are three different factors related to touch deprivation: the absence of touch, longing for touch, and sexual intimacy for touch. First, the absence of touch is the degree to which an individual perceives that touch is not a normal part of their day-to-day interactions. Many people can go days or even weeks without physically having contact with another person. People may surround them on a day-to-day basis at work, but this doesn’t mean that they can engage in physical contact with other people.

Second, there is the longing for touch. It’s one thing to realize that touch is not a normal part of your day-to-day interactions, but it’s something completely different not to have that touch and desire that touch. For some people, the lack of touch can be psychologically straining because humans inherently have a desire for physical contact. For some people, this lack of physical contact with other humans can be satisfied by having a pet.

Lastly, some people desire touch so much that they’ll engage in sexual activity just as a way to get touched by another human being. Obviously, these types of situations can be risky because they involve sexual contact outside of an intimate relationship. In fact, “hooking up” can be detrimental to someone’s psychological wellbeing.9

In the Punyanunt-Carter and Wrench study, the researchers found that there was a positive relationship between touch deprivation and depression and a negative relationship between touch deprivation and self-esteem. The study also found that those individuals who felt that they did not receive enough touch growing up (tactile nurturance) also reported higher levels of touch deprivation as adults. This is just a further indication of how important touch is for children and adolescents.

Vocalics

In this section, we are going to discuss vocalics, that is, vocal utterances, other than words, that serve as a form of communication. Our discussion will begin with vocal characteristics, including timbre, pitch, tempo, rhythm, and intensity.

Timbre

According to Merriam-Webster online dictionary, timbre refers to the “quality given to a sound by its overtones: such as the resonance by which the ear recognizes and identifies a voiced speech sound.” (https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/timbre accessed on November 25, 2018.) Pitch refers to the frequency range between high and low. Pitch is not generally thought of much unless an individual’s pitch stands out. For example, if a female’s vocal pitch is low, meaning might be assigned to the low pitch, just as meaning might be attached to a male voice with a high pitch. Also, pitch that is at a higher or lower end of a range will be noticed if there is a momentary or situational change to an individual’s pitch that will trigger an assignment of meaning. For example, when children become excited or scared, they may be described as “squealing.” The situation will determine whether squealing children are thought to be excited or scared.

Tempo

Tempo refers to the rate at which one speaks. Changes in tempo can reflect emotions such as excitement or anger, physical wellbeing, or energy level. One of the author’s aunts is a brittle diabetic. When talking to her aunt, the author can detect whether the aunt’s blood sugar is too low if her aunt is speaking extremely slow. Rhythm refers to the pattern used when speaking. Unusual speaking rhythms are often imitated. Consider the speaking rhythm of a “surfer dude” or a “valley girl.” One of the most well-known forms of rhythm used in a speech was Martin Luther King, Jr.’s “I have a Dream” speech. More recently, the speaking rhythm of President’s Obama and Trump are easily identifiable and often imitated by comedians.

Intensity

Finally, intensity refers to how loudly or softly an individual speaks. Intensity can be tied to emotion. When individuals speak loudly, the increased volume may be used to convey anger, emotional distress, happiness, or heightened excitement. When individuals speak at a lower volume, the decreased volume may be an effort to diffuse an emotionally intense conversation. Lower volume could also be the result of sharing bad news, discussing taboo or sensitive topics (i.e., when people whisper “sex” or “she died”), or conveying private information.

Other Vocal Features

Paralanguage

Paralanguage is another term for vocalics and refers to “extra-linguistic” features involved in speaking, such as the characteristics of speech just discussed, pauses and silences, and nonverbal vocalizations.

Pauses and Silences

Pauses and silences are an important part of creating meaning during an interaction. Pauses draw attention to important parts of messages. The “pregnant pause” is an extra-long pause that precedes particularly weighty information. Pauses are a type of silence that are brief in nature, but prolonged silence such as minutes, hours, or even days can be used to convey meaning as well. Consider a conversation in which the other person does not respond to you. What meaning is conveyed? Is the individual thinking? Is the individual hurt, angry, or too shocked to speak? Myriad meanings of silence help emphasize the significance of silence and that it is as impactful as verbal communication, if not more so.

Dysfluencies, Vocal Fillers, or Verbal Surrogates

Dysfluencies, vocal fillers, or verbal surrogates are sounds that we make as we attempt to fill dead air while we are thinking of what to say next. In the United States, “um” or “uh” are the most commonly used dysfluencies. In conversation, these dysfluencies may pass unnoticed by both the sender or receiver, but consider how the recognition of dysfluencies increases when listening to a speaker who says “uh” or “um” during a speech. When giving a presentation, the speaker may even call attention to dysfluencies by speaking of them directly, and audience members may become distracted by dysfluencies. One of the author’s classmates used to count the number of “ums” used by a particular professor who was known to frequently use “um” when teaching. Though focusing on dysfluencies may be common, it is best for the speaker to attempt to reduce an excessive amount of dysfluencies and for listeners to focus on the meaning rather than the “ums” and “uhs.”

Kinesics

Kinesics, first coined by Ray Birdwhistell, is the study of how gestures, facial expression, and eye behavior communicate. Gestures can generally be considered any visible movement of the body. These movements “stimulate meaning” in the minds of others.

Facial Expressions

Facial expressions are another form of kinesics. Paul Eckman and Wallace V. Friesen asserted that facial expressions are likely to communicate “affect” or liking.10 Eckman and Freisen present seven emotions that are recognized throughout the world. These emotions are often referred to by the acronym S.A.D.F.I.S.H. and include surprise, anger, disgust, fear, interest, sadness, and happiness. Facial expressions are especially useful in communicating emotion. Although not all facial expression is “universally” recognized, people are generally able to interpret facial expressions within a context. We generally consider happiness is indicated by a smile. Smiling might, however, also communicate politeness, a desire to be pleasing, and even fear. If an individual attempts to use a smile to diffuse a volatile interaction where the individual fears being attacked verbally or physically, then the smile may be an indication of fear. In this case, the smile cannot be accurately interpreted outside of the context.

In a study investigating preferences for facial expressions in relation to the Big Five personality traits, it was found that most participants showed the strongest preferences for faces communicating high levels of agreeableness and extraversion. Individuals who are high in openness preferred a display of all facially-communicated Big Five personality traits. In relation to females who report being highly neurotic, they preferred male faces displaying agreeableness and female faces communicating disagreeableness. Male faces communicating openness were preferred by males who were higher in neuroticism. Interestingly, males reporting higher levels of neuroticism had a lower preference for female faces communicating openness.11 This study underscores the importance of facial expressions in determining who we prefer.

Oculesics

Oculesics is the study of how individuals communicate through eye behavior. Eye contact is generally the first form of communication for interactants. Consider when a stranger speaks to you in a grocery store from behind you with a question such as, “Can you reach the Frosted Flakes for me?” When a general question such as this is asked with no eye contact, you may not be aware that the question was meant for you.

Often when discussing eye behavior, researchers refer to “gaze.” Research consistently demonstrates that females gaze at interaction partners more frequently than males.12,13,14 Also, gaze has been studied concerning deception. Early research determined the significance of eye contact in the interpretation behavior. When people gaze too long or for too little, there is likely to be a negative interpretation of this behavior.15 However, later researchers acknowledge that there is a much greater range of acceptable “gazing” as influenced by verbal communication.

Gestures

Kinesics serve multiple functions when communicating—such as emblems, illustrators, affect displays, and regulators.

Emblems

Many gestures are emblems. You may recall from earlier in the chapter that gestures are clear and unambiguous and have a verbal equivalent in a given culture.16 Only a handful of emblematic gestures seem to be universal, for example, a shrug of the shoulders to indicate “I don’t know.” Most emblems are culturally determined, and they can get you into difficulty if you use them in other countries. In the United States, some emblematic gestures are the thumb-up-and-out hitchhiking sign, the circled thumb and index finger Ok sign, and the “V” for victory sign. However, be careful of using these gestures outside the United States. The thumb-up sign in Iran, for example, is an obscene gesture, and our Ok sign has sexual connotations in Ethiopia and Mexico.17

Illustrators

While emblems can be used as direct substitutions for words, illustrators help emphasize or explain a word. Recall the Smashmouth lyric in All Star: “She was looking kind of dumb with her finger and her thumb in the shape of an L on her forehead.” The “L” gesture is often used to illustrate “loser.”

Affect Displays

Affect displays show feelings and emotions. Consider how music and sports fans show enthusiasm. It is not uncommon to see grown men and women jumping up and down at sports events during a particularly exciting moment in a game. However, there are different norms depending on the sport. It would simply be inappropriate to demonstrate the same nonverbal gestures at a golf or tennis game as a football game.

Regulators

Regulators, as discussed earlier, are gestures that help coordinate the flow of conversation, such as when you shrug your shoulders or wink. Head nods, eye contact/aversion, hand movements, and changes in posture are considered to be turn-taking cues in conversation. Individuals may sit back when listening but shift forward to indicate a desire to speak. Eye contact shifts frequently during a conversation to indicate listening or a desire to speak. Head nods are used as a sign of listening and often indicate that the speaker should continue speaking.

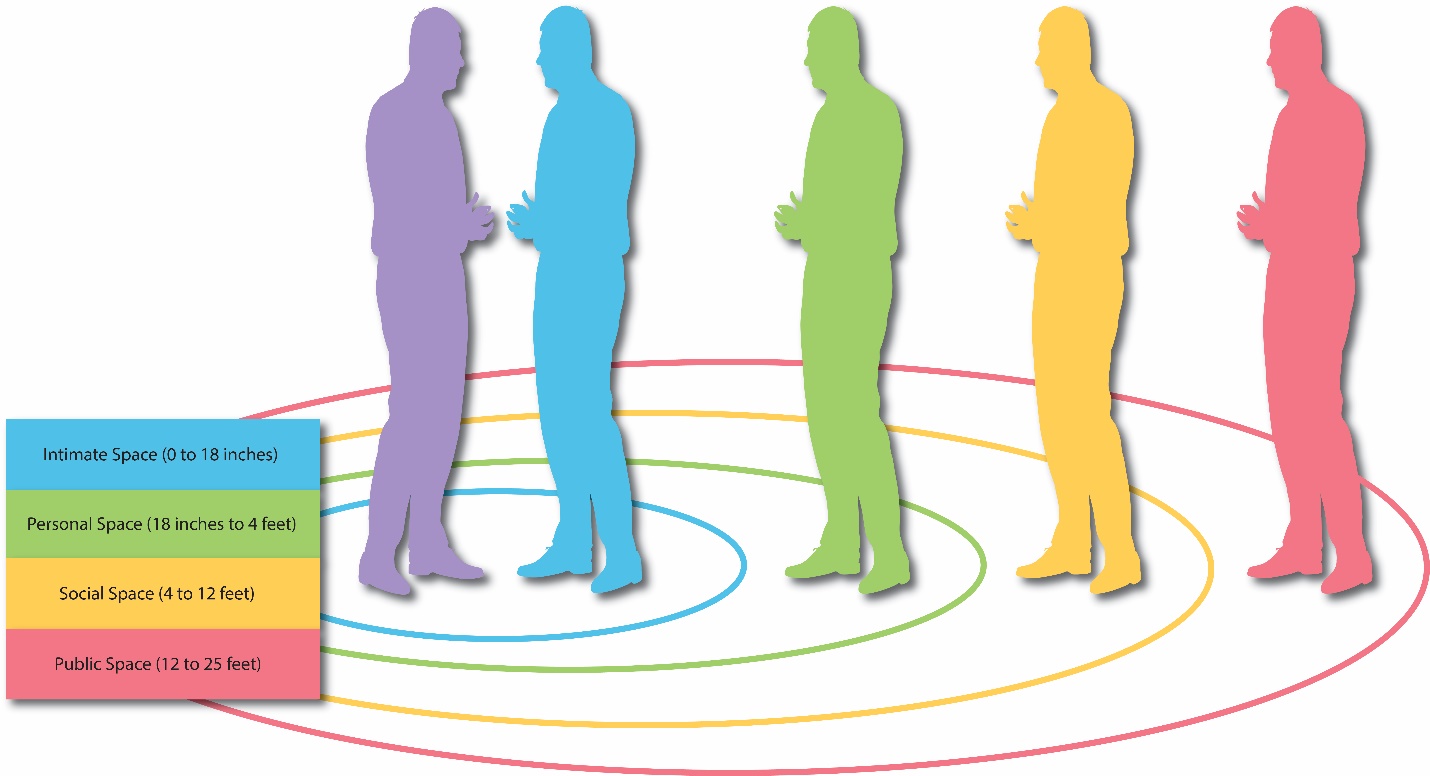

Proxemics

Proxemics is the study of communication through space. Space as communication was heavily studied by Edward T. Hall,18 and he famously categorized space into four “distances. These distances represent how space is used and by whom (Figure 5.4).

Figure 7.2

Edward T. Hall’s Four Spaces

Hall’s first distance is referred to as intimate space and is often referred to as our “personal bubble.” This bubble ranges from 0 to 18 inches from the body. This space is reserved for those with whom we have close personal relationships.

The next distance is referred to as personal space and ranges from 18 inches to 4 feet. You will notice that, as the distances move further away from the body, the intimacy of interactions decreases. Personal space is used for conversations with friends or family. If you meet a friend at the local coffee shop to catch up on life, it is likely that you will sit between 18 inches and four feet from your friend.

The next distance is “social” distance, ranging from 4 feet to 12 feet. This space is meant for acquaintances.

Finally, the greatest distance is referred to as “public” distance, ranging from 12 feet to 25 feet. In an uncrowded public space, we would not likely approach a stranger any closer than 12 feet. Consider an empty movie theatre. If you enter a theatre with only one other customer, you will not likely sit in the seat directly behind, beside, or in front of this individual. In all likelihood, you would sit further than 12 feet from this individual. However, as the theatre begins to fill, individuals will be forced to sit in Hall’s distances that represent more intimate relationships. How awkward do you feel if you have to sit directly next to a stranger in a theatre?

Artifacts

Artifacts are items with which we adorn our bodies or which we carry with us. Artifacts include glasses, jewelry, canes, shoes, clothing, or any object associated with our body that communicates meaning. One very famous artifact that most everyone can recognize is the glasses of Harry Potter. Harry Potter’s style of glasses has taken on their own meaning. What does his style of eyewear communicate when donned by others? Clothing also stimulates meaning. Do you recall Barney Stinson’s famous line “suit up” in How I Met Your Mother? Why was it necessary to suit up? Recently, Snoop Dogg was given a star on the Hollywood Walk of Fame. Snoop Dogg was wearing a beautiful, classic camel hair overcoat. In contrast, he was wearing large bulky jewelry. What do these two types of artifacts communicate? One of the authors is a big fan. The author interpreted the classic overcoat as Snoop having excellent taste and the jewelry as strength and wealth. Together the artifacts were interpreted as power.

Chronemics

Chronemics, as explained by Thomas J. Bruneau,19 is the use of time to communicate. The use of time is considered to be culturally bound, with some cultures using monochronic time and others using polychronic time. Cultures using monochronic time engage in one task at a time. Cultures using polychronic time engage in multiple tasks at the same time. This use of time involves fluidity with individuals feeling free to work on multiple tasks simultaneously rather than completing a task before moving to the next task, as in the monochronic use of time. When considering how time is used, it is necessary to consider individual preferences as well as cultural preferences. Traditionally, the U.S. is a monochronic culture along with Canada or Northern Europe. Korea is an example of a polychronic culture along with Latin America, the Arab part of the Middle East, and Sub-Saharan Africa. However, one can live in each of these cultures and express the opposite orientation toward time. One of the authors is admittedly uptight when it comes to time. She is highly monochronic. This author went to a conference in Puerto Rico, which represents a polychronic orientation toward time. Buses usually run 30 minutes late, if not longer. Time is a bit more fluid rather than incremental in polychronic cultures. Unfortunately, the author failed to take this into account and nearly missed a presentation. This resulted in stress that could have been avoided had she remembered to pay more attention to the time orientation of those around her.

Olfactics

Finally, olfactics generally refers to the influence of scent on perceptions. Scent can draw others in or repel them, and the same scent can have different impacts on different people. According to statistica.com, the global estimated sales value of the fragrances worldwide in 2016 was $47 billion U.S. dollars. This is in addition to $39 billion U.S. dollars in shower and bath products and another $20.5 billion in deodorants. The total spending in these categories was $106.5 billion U.S. dollars. These figures underscore the importance of “smelling good” across the globe. Consider the impact of failing to manage one’s natural scent in the workplace. Countless articles in the popular media address how to deal with a “smelly coworker.” Thus, it is crucial to be aware of one’s scent, including the ones we wear in an effort not to offend those around us. Although smelling “bad” may end a relationship or at least create distance, an attractive scent may help individuals begin a new relationship. Have you ever purchased a new scent before a first date? If so, you are aware of the power of scent to attract a mate. Although we regularly try to cover our scent, we also attempt to control the scent of our environments. The air freshener market in 2016 was valued at $1.62 billion U.S. dollars. Go to your local grocery store and investigate the number of products available to enhance environmental scents. Be prepared to spend a significant amount of time to take in the many products to keep our environments “fresh.”20

The amount of money spent on fragrances for the body and home highlights the meaning of scent to humans. Ask yourself the following questions:

- What meaning do you associate with a floral scent vs. a spicy scent?

- When comparing men’s fragrances to women’s fragrances, what differences do you notice?

- Are there scents that immediately transport you back in time, such as the smell of honeysuckle or freshly baked cookies?

Regardless of the scent you prefer, when using scent to communicate positively with others, do not make the mistake of believing the scent you like is loved by those around you!

Physical Appearance

Although not one of the traditional categories of nonverbal communication, we really should discuss physical appearance as a nonverbal message. Whether we like it or not, our physical appearance has an impact on how people relate to us and view us. Someone’s physical appearance is often one of the first reasons people decide to interact with each other in the first place.

Dany Ivy and Sean Wahl argue that physical appearance is a very important factor in nonverbal communication:

The connection between physical appearance and nonverbal communication needs to be made for two important reasons: (1) The decisions we make to maintain or alter our physical appearance reveal a great deal about who we are, and (2) the physical appearance of other people impacts our perception of them, how we communicate with them, how approachable they are, how attractive or unattractive they are, and so on.21

In fact, people ascribe all kinds of meanings based on their perceptions of how we physically appear to them. Everything from your height, skin tone, smile, weight, and hair (color, style, lack of, etc.) can communicate meanings to other people.

The Matching Hypothesis

One obvious area where physical appearance plays a huge part in our day-to-day lives is in our romantic relationships. Elaine Walster and her colleagues coined the “matching hypothesis” back in the 1960s.32,33 The basic premise of the matching hypothesis is that the idea of “opposites attracting” really doesn’t pertain to physical attraction. When all else is equal, people are more likely to find themselves in romantic relationships with people who are perceived as similarly physically attractive.

In a classic study conducted by Shepherd and Ellis, the researchers took pictures of married couples and mixed up the images of the husbands and wives.34 The researchers then had groups of female and male college students sort the images based on physical attraction. Not surprisingly, there was a positive relationship between the physical attractiveness of the husbands and the physical attractiveness of the wives.

Other physical appearance variables beyond just basic physical attractiveness have also been examined with regards to the matching hypothesis. A group of researchers led by Julie Carmalt found that matching also explained the dating habits of young people.35 In their study, Carmalt et al. found that individuals who were overweight were less likely to date someone who was physically attractive.

Overall, research generally supports the matching hypothesis, but physical attractiveness is not the only variable that can impact romantic partners (e.g., socioeconomic status, education, career prospects, etc.). However, the matching hypothesis is a factor that impacts many people’s ultimate dating selection ability.

Research Spotlight

In a series of different studies, Shaw Taylor et al. tested the matching hypothesis. In one of the studies, the researchers collected the data for 60 females and 60 males on online dating platforms (we’ll refer to these 120 people as the initiators). They then used the site activity logs to collect information about who the initiators matched with on the dating website and whether those people responded. Based on this contact information, the researchers also collected the pictures of those people who were contacted, so the researchers collected 966 photos (527 female, 439 male). The physical attractiveness of the group of photos was evaluated on a scale of very unattractive (-3) to very attractive (+3) by people within the authors’ department.

In a series of different studies, Shaw Taylor et al. tested the matching hypothesis. In one of the studies, the researchers collected the data for 60 females and 60 males on online dating platforms (we’ll refer to these 120 people as the initiators). They then used the site activity logs to collect information about who the initiators matched with on the dating website and whether those people responded. Based on this contact information, the researchers also collected the pictures of those people who were contacted, so the researchers collected 966 photos (527 female, 439 male). The physical attractiveness of the group of photos was evaluated on a scale of very unattractive (-3) to very attractive (+3) by people within the authors’ department.

Matching behavior (or swiping right) was not based on the initiator’s physical appearance. So, people often matched with others who were physically more attractive than them. However, people only tended to respond to initiators when their physical attractiveness was similar.

Shaw Taylor, L., Fiore, A. T., Mendelsohn, G. A., & Cheshire, C. (2011). “Out of my league”: A real-world test of the matching hypothesis. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 37(7), 942–954. https://doi.org/10.1177/0146167211409947

Key Takeaways

- Communication is multifaceted with the combination of verbal and nonverbal cues culminating in a richer communication experience.

- Vocal cues such as rate, pitch, and volume have an impact on whether communication is effective.

- Facial expressions and body movements enhance communication, but may detract from the effectiveness of communication.

Improving your Nonverbal Skills

In this chapter, we’ve examined a wide range of issues related to nonverbal communication. But it’s one thing to understand nonverbal communication and something completely different to communicate using nonverbal behaviors effectively. In this section, we’re going to explore some ways that you can start to improve your nonverbal skills.

The Nonverbal Mindset

When it comes to effective communication, you need to develop an appropriate mindset towards nonverbal communication. First, individuals must be aware that nonverbal communication plays a significant role in creating meaning.

Second, individuals must believe nonverbal communication is important and impactful. Awareness of nonverbal communication without the belief that it is important can result in negative outcomes. For example, students in nonverbal communication begin to learn about the importance of clothing and general appearance in creating impressions. Some students “rebel” against the idea that appearance and clothing matter stating, “people should accept me no matter what I am wearing.” While this would be ideal, the fact of the matter is that humans size up other humans using visual cues in initial interactions.

Lastly, individuals can analyze their nonverbal communication. This can be accomplished in several ways. Individuals might observe the behavior of individuals who seem to be liked by others and to whom others are socially attracted. The individual should then compare the behaviors of the “popular” person to their own behaviors. What differences exist? Does the other individual smile more, make more or less eye contact, engage in more or less touch, etc.? Based on this comparison, individuals can devise a plan for improvement or perhaps no improvement is needed!

Nonverbal Immediacy

In addition to awareness of nonverbal communication, believing that nonverbal communication is important and analyzing one’s own behavior, individuals should be aware of nonverbal immediacy. Immediacy is defined as physical and psychological closeness. More specifically, Mehrabian defines immediacy as behaviors increasing the sensory stimulation between individuals.36 Immediacy behaviors include being physically oriented toward another, eye contact, some touch, gesturing, vocal variety, and talking louder. Immediacy behaviors are known to be impactful in a variety of contexts.

In instructional, organizational, and social contexts, research has revealed powerful positive impacts attributable to immediacy behaviors, including influence and compliance, liking, relationship satisfaction, job satisfaction, and learning, etc. In the health care setting, the positive outcomes of nonverbally immediate interaction are well documented: patient satisfaction,37,38 understanding of medical information,39,40 patient perceptions of provider credibility,41 patient perceptions of confidentiality,42 parent recall of medical directives given by pediatricians and associated cognitive learning,43 affect for the provider,44,45 and decreased apprehension when communicating with a physician.46 Individuals can increase their immediacy behaviors through practice!

Key Takeaways

- Voice, body movement, eye contact, and facial expression can be assessed and improved upon to become a more effective communicator.

- Successful communicators can be observed and modeled.

- Practicing nonverbal communication is no different from practicing other skills, such as playing an instrument or cooking.

Chapter Wrap-Up

In this chapter, we discussed the importance of nonverbal communication. To be an effective nonverbal communicator, it is necessary to understand that nonverbal communication conveys a tremendous amount of information. However, the meaning of nonverbal communication most often must be understood within the context of the interaction. There are very few nonverbal behaviors that can be understood outside of context.

This chapter also discusses the functions of nonverbal communication. Nonverbal communication serves many purposes and works to clarify the meaning of verbal communication. Verbal communication and nonverbal communication, in combination, increase the chances of stimulating accurate meaning in the minds of others. One without the other dilutes the effectiveness of each.

Finally, this chapter discusses the subcategories of nonverbal communication. The subcategories of nonverbal communication allow us to account for the multitude of cues sent between the sender and receiver. The human brain must account for cues resulting from eye contact, facial expressions, distance between sender and receiver, touch, sound, movement, and scent. Amazingly, the human brain processes all of these cues very quickly and with a high degree of accuracy.

References

“Nonverbal Communication” by Dr. Kathryn Weinland is adapted from “Nonverbal Communication” in Interpersonal Communication by Jason S. Wrench, Narissra M. Punyanunt-Carter, and Katherine S. Thweatt, licensed CC BY-NC-SA.