16 Writing an Empirical Research Report

Empirical Research

Empirical research uses information gathered from primary sources to answer a research question. You may recall from reading about scholarly articles that empirical research reports are a major subgenre of scholarly article. Empirical research reports are also, essentially, a very specialized type of argument of fact.

Different disciplines engage in empirical research in slightly different ways; this chapter presents empirical research as it is typically addressed in the natural and social sciences. Scholars in fields like literature, art, philosophy, and history also conduct empirical research (primarily analyzing texts or other artifacts), but they often don’t quite follow the standard structure that I describe in this chapter. However, you technically can use this structure for any type of empirical research; it just wouldn’t be the conventional way it’s done in the humanities.

Empirical Research Questions

Empirical research starts with a question that you want to answer and that can be answered empirically. (Refer back to the chapter on Arguments of Fact for more about empirical evidence.) You will probably start first with a broad topic or question and gradually narrow that question down as you consider the following issues:

- What are you able to find relevant, scholarly secondary sources about?

- What can you realistically accomplish with the time and other resources you have?

- What kind(s) of primary source data are you interested in collecting?

The remaining sections of the chapter walk you through the process of identifying and refining your research question, collecting your data, and writing up your final report. You’ll probably go more or less in order, but keep in mind that it’s very normal – and often necessary – to jump back and forth between steps.

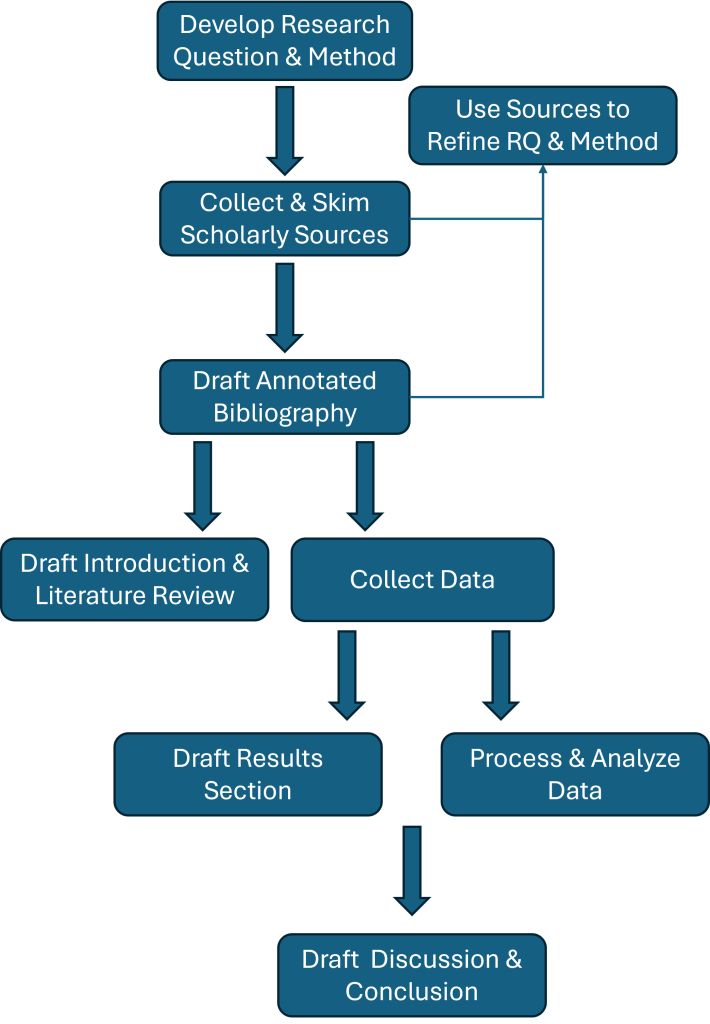

Here is a diagram showing a typical sequence for an empirical research project:

You may notice that there are a lot of steps! This diagram shows a pretty direct path from beginning to end, but keep in mind that reality is often much messier and less linear; it’s normal and expected if your process doesn’t end up looking quite this tidy.

Selecting a Research Question

A good first step to picking a good research question (called an RQ for short) is to just start by listing topics that are interesting to you. Be open-minded in this phase. Include things that you think are cool or interesting, that you’re curious about, or that you may be already know a lot about. Once you have this list, pick the 3-4 ideas that you’re most interested in pursuing. Don’t worry yet about whether they’ll actually work; odds are they’ll need some refinement, no matter what. It is possible that none of your top 3-4 ideas will end up working out, in which case you can always come back to your larger list, but that’s pretty uncommon.

As noted above, you will need to use scholarly sources to provide background and context for your research, so a good next step is a library search to see what’s out there on these 3-4 topics. Your topics are probably broad, and you can use this search to help you narrow them down, too.

As you review the sources available on your topic, you should focus on recent scholarly articles, and more specifically on empirical research reports. Pay attention to the research questions they address and the methods they use, as you could potentially use these as models for your own work. You should also be looking for themes, or recurring ideas that pop up in multiple articles. These themes should help you understand what areas of the topic are currently being explored by scholars.

As you work, jot down potential research questions that come to mind. You may find that a topic that started out as a favorite isn’t really offering you any great ideas for empirical research, and that’s fine. Hopefully, though, you end up with a list of at least few research questions that seem interesting to you.

Deciding on a Research Method

Your next step is to consider whether and how you can use primary research to answer these research questions. Your research method is how you plan to collect data from primary sources to answer your research question. What constitutes a primary source largely depends on what you are doing with the source. Primary source material is anything that provides firsthand evidence to answer a research question. It is distinct from the kinds of sources you are probably used to using, which are typically secondary sources that provide someone else’s – usually an expert’s – information, arguments, or analysis.

You collect primary source data directly, typically by interviewing or surveying people, by designing and running experiments, by carefully observing settings or events, or by finding and examining artifacts or texts.

The examples in the table below illustrate the relationships among research questions, primary sources, and secondary sources. Note how, in every case, the primary source provides direct information to answer the research question, while the secondary sources may provide either other people’s attempts to answer the same question or background information about the topic(s) involved.

| Research Question | How One Might Collect Primary Research Data | How One Might Collect Secondary Research Data |

| How do followers of the keto diet feel about others who don’t follow keto? | Interview and/or survey followers of the keto diet; observe social media posts in keto diet groups and/or posts by keto followers | Find books and articles about the relationship between fad diets and attitudes/emotions |

| How accurately is forensic science portrayed in the TV show Blue Bloods? | Watch Blue Bloods and collect examples of how forensic science is shown or talked about | Find books and articles about forensic science and/or about how forensic science is portrayed on television |

| How has Covid-19 affected the experience of nurses? | Interview and/or survey nurses | Find books and articles about how Covid-19 affected nurses/the nursing profession |

| How much faster are people at solving crossword puzzles when they are well-rested compared to when they are tired? | Set up an experiment to observe and time people solving crossword puzzles when they are tired and when they are well-rested | Find books and articles about rest and cognitive function |

| How are today’s depictions of female beauty different from 20 years ago? | Find images of models or celebrities commonly considered beautiful from 20 years ago and today to compare them | Find books and articles about beauty, beauty standards, and related cultural ideals and how these change over time |

| How does the distance of a person’s car from the nearest shopping cart return relate to the likelihood of a person returning their cart? | Observe a parking lot as often and for as long as possible, tracking who returns carts and how far their car was from the shopping cart return. | Find books and articles about the relationship between convenience and ethical behavior/choices |

| What is the underlying message of the book Mansfield Park by Jane Austen? | Read Mansfield Park and identify plot points and/or specific passages that convey particular lessons | Find books and articles about Mansfield Park, Jane Austen, themes in Georgian novels, and literary analysis |

Note that though it is technically possible for nonfiction articles or books about a topic to serve as primary source material, those scenarios are quite unusual. If you find yourself thinking, “I’m collecting data by reading articles about my topic,” that’s probably not primary research!

A clear idea of your method should incorporate answers to these questions:

- Who or what will you be collecting data from?

- Where, when, and how will you collect that data?

Troubleshooting Your Research Question and Method

There are few common pitfalls students run into at this point in planning their projects. Once you have a research question and method in mind, take a moment to evaluate your idea on the three key criteria described below: alignment, feasibility, and ethics.

Alignment

Students sometimes struggle to make a good “match” (also known as alignment) between their proposed research question and their planned primary source material. For example, you may wonder how having a family member with dementia affects people’s family relationships, and then propose interviewing people who have family members with dementia. However, interviewing people doesn’t tell you directly what the effects are; it only tells you what people say the effects are. People aren’t always honest, unbiased, or accurate, even when describing their own lives. A more appropriate research question for this type of primary source data might be something like, “How do people who have family members with dementia describe the effects on their family relationships?” The difference is subtle, but important; the revised question is one that can actually be answered with information collected by interviewing these people.

Another common error is assuming that any data collected from interviews will always be considered primary source data. However, interviews can be secondary sources. If you interview someone about a topic simply because you want their expertise on it, you are using that person as a secondary source; it’s not really any different from if you cited an article they wrote about the topic. Consider, for example, a scenario where your research question is, “What are the most common hurdles new nurses experience on the job?” You can certainly ask your nursing faculty about this, but the question as written suggests that the most direct information would come from new nurses themselves. You would want to either revise the research question (to something like, “What do nursing faculty believe are the most common hurdles new nurses experience on the job?”) or plan to just interview new nurses instead. (You could still interview experienced nurses, too, but you would either focus the interview on having them describe just their early experiences on the job or use their information as secondary source material.)

To evaluate the alignment of your planned research question and method, consider whether your planned primary source material truly represents the most direct way to find an accurate answer your research question. If it doesn’t, either the research question or the method needs to be revised.

Feasibility

You also need to consider the constraints on your time and other resources. Many students have really ambitious project ideas that would be too big for professional researchers to take on, let alone for a project that will last only a few weeks. Be realistic about the time you have to invest in the project and carefully consider your access to any special tools or skills you might need to conduct the research as you’re envisioning it.

Ethics

Because you’re students and not conducting this research as professionals who intend to publish, you don’t have to go through all of the training and paperwork that professional researchers do. Anyone who conducts research professionally is required to take ethics training and keep their certifications up to date, and they have to submit their research proposals to an Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC) for research involving animals, or to an Institutional Review Board (IRB) for research involving humans. The IACUC or IRB verifies that their planned research is safe and ethical and provides oversight to make sure the researcher doesn’t violate any rules in the process of conducting research.

However, just because you’re not required to jump through all of those hoops, you should still adhere to the ethical principles of conducting research. In fact, because you do not have the training that professional researchers do, you should be even more careful in some ways. Never do anything invasive or that might cause any distress to your research subjects (human or animal). Sometimes professional researchers have to do these things, but they are carefully trained in minimizing the harm, and they have to justify the need for such research. Your research will not meet that standard.

If you are collecting data involving people in any way, make sure your research plan adheres to the principles of:

- Informed Consent – Be sure to let people know what you are doing and why, and make sure they know they can opt out or change their minds, even if they previously said they would participate. If you plan to collect data from minors, you have a little bit of leeway if those minors are your classmates, but check with your instructor first to be sure; ethical guidelines for research involving minors are very strict.

- Privacy – Respect people’s privacy. Ask permission to use their real names, to record audio or video, and be careful not to provide identifiable information when you report your results. Only conduct observations in public places.

If you are collecting data involving animals, make sure your research plan adheres to the principles of:

- Humane Care – Animals must be provided appropriate care and conditions.

- Noninvasive Procedures – Any procedures should be noninvasive and not cause the animal distress.

A good rule of thumb for animal research is whether you are doing something that might ordinarily be done in the course of normal animal care. For example, I have had students who ran experiments on their own pets testing different methods of training. Trying out ways to train your pets is a perfectly normal thing to do, so I didn’t have any ethical concerns about those projects.

Conducting Background Research: The Literature Review

Your next step is to start combing through scholarly sources on the topic so you can provide a brief literature review. (Note that literature reviews can also be written as stand-alone essays.) The literature review synthesizes other scholarly work on the topic to accomplish two main tasks:

- To explain the background/history of the topic

- To describe the current state of research on the topic (what questions or debates interest scholars right now)

When incorporated into your own empirical research report, the literature review should provide the justification for your specific research:

- By showing that the research question is currently relevant/significant

- By showing that previous studies on the specific question need replication, haven’t been consistent, or do not exist

- By providing theoretical frameworks or perspectives that guide your study

To start the literature review, consider creating an annotated bibliography. An annotated bibliography is a list of source citations, with each citation followed by a brief summary of the source. (Be sure to write the summary yourself, even if the source has an abstract!) When you have all of these summaries together in one place, it can be easier to identify common themes and organize the sources in a way that will help you provide the necessary background and context for your own study.

The literature review should critically analyze and summarize the key findings, theories, and methodologies from prior research related to your topic and question. It demonstrates your comprehensive understanding of the existing knowledge base. The review should highlight gaps, inconsistencies, or areas that need further investigation, making a strong case for why your proposed study is important and fills a void. The literature review essentially lays the groundwork by situating your study within the broader scholarly conversation.

As you work on this background research, you may find that you need or want to revise your research question and/or method. That’s expected and perfectly acceptable. Just make sure your new RQ and method are still aligned, feasible, and ethical.

Collecting Your Data

Be sure to allow plenty of time for this step; it often takes longer than you expect! In fact, you’ll probably have to start collecting your data before you really feel ready to start collecting your data. If it’s possible to do a trial run of your survey or interview questions or of your experimental design before you officially begin collecting data, I highly recommend doing so. It will give you a chance to iron out any little problems before they cause bigger issues later.

Writing the Report

Empirical research reports typically follow a structure that is often abbreviated as IMRD: Introduction, Method, Results, and Discussion. In practice, the Conclusion is often consolidated with the Discussion, but I find it useful to think of it as a separate section. The contents of each of these sections are described below, but keep in mind that there are certainly variations on this format.

- Introduction

- Opening paragraph establishes research area and its significance.

- Multiple paragraphs of literature review follow.

- The final paragraph of the introduction section identifies the research question of interest and connects it to the preceding literature review.

- Methods

- Describes, in detail, the who, what, when, where, and how of data collection.

- Results

- Presents the data that were collected.

- Discussion

- Discusses how the data does/does not answer the research question.

- Connects the study’s findings back to the literature that was covered in the literature review.

- Conclusion

- Suggests how study’s findings could be applied.

- Describes limitations of the study.

- Identifies avenues for future research.

Documenting Your Sources

You will, of course, document your secondary sources in the usual manner. How you document your primary source material varies a bit depending on whether you are following MLA or APA guidelines, and what kind of primary research you conducted. The two tables below describe how to cite your primary research according to MLA (Table 1) and APA (Table 2).

Table 1

MLA Guidelines for Documentation of Primary Source Data

| Type of Source | In-Text Citations | Works Cited |

| Documents or Media (TV shows, movies, songs, etc.) | Follow standard rules | Follow standard rules |

| Interviews | Follow standard rules. If using a pseudonym for the interviewee, be sure to indicate this in the text. | Cite interviewee (real name or pseudonym), type of interview (presumed to be in-person unless otherwise specified), and date. If you are working alone on the project, specify that the interview was conducted with the author. If you are working with a partner or group, specify which group member conducted the interview.

Lastname, Firstname. Type of interview with the author. Date. Lastname, Firstname. Type of interview. Conducted by whom. Date. Examples: Doe, Jane. Interview with the author. 4 Aug. 2022. Doe, Jane. Telephone nterview. Conducted by Joe Blow. 4 Aug. 2022.

|

| Survey Data | Per MLA Style Center:

In a report on data collected from a survey you designed and distributed, clarify the data source in the body of the report instead of creating a works-cited-list entry for the survey. Be sure to explain in detail the methodology you used—that is, how you distributed the survey and collected and sorted responses. It’s also good practice to make the survey instrument available to readers, either by including it as an appendix to your report or by providing a link to it in an endnote. Some researchers even make their data sets available to readers, often in an Excel file. You may want to anonymize your data in the report on your findings. There are two options for anonymizing survey responses: you can use generic language to report a finding (e.g., “one respondent commented …”), or you can use pseudonyms for respondents. If you decide to use pseudonyms, place a note at the first instance that indicates that the names of survey respondents have been changed to preserve their anonymity. |

|

| Experimental or Observational Data | MLA does not provide guidance about citing one’s own experiments/observations, but presumably the statement above regarding raw data from surveys can be applied to this data as well. | |

Table 2

APA Guidelines for Documentation of Primary Source Data

| Type of Source | In-Text Citations | References |

| Documents or Media (TV shows, movies, songs, etc.) | Follow standard rules | Follow standard rules |

| Interviews | Per the APA Handbook (7th edition):

When quoting research participants, use the same formatting as for other quotations. . . . Because quotations from research participants are part of your original research, do not include them in the reference list or treat them as personal communications; state in the text that the quotations are from participants. When quoting research participants, abide by the ethical agreements regarding confidentiality and/or anonymity between you and your participants. Take extra care to obtain and respect participants’ consent to have their information included in your report. You may need to assign participants a pseudonym [or] obscure identifying information. (p. 278) |

|

| Survey Data | Per Purdue OWL:

Since a survey you conducted yourself is not published elsewhere by someone else, you do not cite it in the same way you cite other materials. Instead, in your paper you describe your survey and make it clear that the data you’re referring to is from the survey, usually by saying so in introductory sentences. In your paper, you should include a short overview of your survey method: whom the survey was administered to, how it was administered, how many responses you got, and what kind of questions you asked. You should include a copy of the survey instrument (the full set of questions asked) as an appendix to your paper. You do not need to include your survey in your reference list. |

|

| Experimental or Observational Data | Because these would also be unpublished information used for your original research, they will not be cited. The APA Handbook (7th edition) does recommend including details that may “help readers understand, evaluate, or replicate the study” in an appendix if they “are relatively brief and easily presented in a print format” (p. 41). | |