2 Reading Well

Reading with Critical Engagement

You can expect to do a lot of reading for your college classes. You may expect that a professor will assign a reading because they want you to simply remember the content of what you’ve read, and that may sometimes be the case, especially when you’re reading from a textbook. However, at the college level, reading is generally not a passive activity where you are simply expected to retain the information. Instead, often you will need to go beyond remembering or understanding information from a reading. You may need to apply what you’ve learned, make an argument about what you’ve read, or synthesize information from multiple reading assignments to create your own written work. To accomplish those tasks, you need to read with a more critical mindset about the text. Instead of passively taking in information, you should be engaging with the text by responding, asking questions, and making connections.

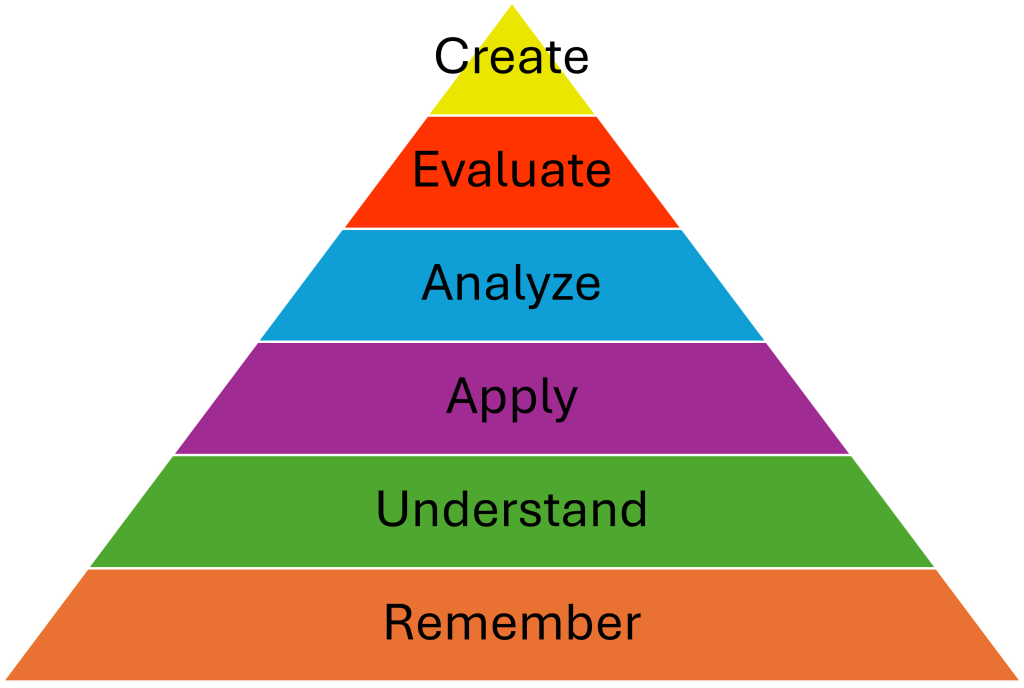

To accomplish those critical reading tasks, it can be helpful to understand Bloom’s taxonomy of cognitive skills. Educational theorist Benjamin Bloom developed a taxonomy of cognitive tasks based on how challenging or complex each task is; successfully completing tasks at the top of hierarchy depends on one’s ability to complete tasks at the bottom of the hierarchy. Bloom’s taxonomy looks like this:

When we think about reading for college, these might look like the following tasks:

- Remember – Be able to recall key arguments and details from texts.

- Understand – Be able to explain the meaning of a text in your own words.

- Apply – Be able to use the ideas from a text in a new context.

- Analyze – Be able to explain connections and relationships between texts.

- Evaluate – Be able to make an argument about a text.

- Create – Be able to propose changes to a text.

At the college level, you’ll often be asked to analyze, evaluate, and create; thus, you’ll want to read with these goals in mind. The great thing about aiming high on Bloom’s taxonomy is that the lower levels are then automatically covered. If you know a reading well enough to make a strong argument about it, you certainly remember it well enough to pass a multiple choice test as well. So how do you read in a way that makes this possible?

- Identify the original context of the piece. Where and when was it originally published? Who was the originally intended audience? If the original publication was a newspaper or magazine you don’t know much about, Wikipedia can be a great resource for a general description of what kinds of topics the publication typically covers and what their readership is like.

- Use pre-reading strategies like skimming the headings. This practice will give you a sense of the main ideas and how the text is organized, before you dig into the details.

- Annotate what you read! Don’t just highlight main ideas; make marginal notes. Have you ever been reading and suddenly realized you weren’t actually paying attention to the words, even though your eyes were passing over them? Marginal notes force you to engage with the text’s content. Common marginal types of marginal notes include things like:

-

- Jotting down the main topic or point of a section in your own words

- Noting questions about what is meant

- Commenting on the writing style

- Identifying your own thoughts or feelings in response to what you’re reading

- Write about what you read! After you complete a reading, write a brief summary or even a response. This practice will cement the text in your memory, as well as give you an opportunity to organize and articulate your opinions about it.

- Talk about what you read! Having conversations is an important learning tool because it allows you to engage in dialectic. Dialectic involves discussing your responses with others, particularly people who will challenge or contradict your views. Through dialectic, you are able to refine your ideas.

Summary Writing

A summary is simply a brief, objective description of a text’s main ideas. The key aspect of a summary is that it’s much shorter than the original text, focusing only on main ideas and omitting supporting details.

Learning how to write good summaries will serve you in many ways in your college career. Summaries of others’ works often serve as background or supporting information in your own writing, but they can also be useful tools to help you organize research when you have to evaluate and synthesize information from different sources. A good summary:

- Identifies the author, title, and original publication context of the work being summarized

- Is written in your own words, with few or no quotations from the work being summarized

- Clearly articulates the main point (and not just the topic) of the work being summarized

- Thoroughly and accurately reflects the supporting reasons and evidence provided in the work being summarized

- Does not convey (even subtly) your opinion of or response to the work being summarized

- Uses frequent attributive tags (phrases like “according to Author” or “Author argues”) to remind the reader that someone else’s work is being summarized

Summaries are always shorter than the work being summarized, but they can otherwise vary greatly in length, depending on your purpose. When I was in graduate school, I had a professor who required us to write a one-sentence summary of each book we read (yes, we read multiple books for one class!). That exercise turned out to be really useful because I was forced to figure out the main point of an entire book and put that point into my own words. However, those summaries weren’t detailed enough to use for something like an annotated bibliography. Most summaries you write for academic work will be somewhere between several sentences to a full page.

A good strategy for getting started on your summary is to use the opening sentence to identify the author’s full name, the text’s title, the original publication title (the name of the magazine or website where an article was published), and the text’s main idea. You can also incorporate other contextual details that you think are relevant; for example, readers might benefit from knowing the year a source was published, the genre of a source, or the background of the author. Here are some examples of strong opening sentences:

- In the 1932 article “In Praise of Idleness” from The Atlantic, philosopher Bertrand Russell argues that Western society puts too much emphasis on work and productivity, and that we would be better off if we valued leisure more.

- In “True Crime Distorts the Truth about Crime” from the magazine Reason, Kat Rosenfield asserts that true crime media often exploits victims in the name of creating a tidy narrative that appeals to audiences.

- In the Transcultural Psychiatry article “Technology and Addiction: What Drugs Can Teach Us about Digital Media,” researchers Ido Hartogsohn and Amir Vudka critique the common discourse that describes digital media as addictive, arguing that this view, though accurate in some senses, also limits our ability to develop healthier approaches to our engagement with digital media.

- In the book Thinking, Fast and Slow, Daniel Kahneman describes numerous studies that show how humans use mental shortcuts that can lead to misunderstandings and bad decisions, and illuminates how we can become more aware of these shortcuts to slow down our thinking when we need to.

Note how each of the above sentences uses the author(s) as the subject of the sentence. This is good practice, as it’s how you’ll be expected to refer to sources throughout your academic writing, but it’s also an easy way to streamline the sentence. When you have to cram in so much contextual information, it’s easy for the opening sentence to become clunky or even ungrammatical.

In some contexts, a single-sentence summary may be sufficient. However, in most cases, you’ll be expected to expand the summary a bit more by including brief descriptions of the key supporting arguments or main ideas. The most important factor to keep in mind as you flesh out the summary to the expected length is proportion.

Sometimes, people get overly focused on just one particular idea from the text – whether it’s the idea they liked or disliked the most, or simply the part they understood the best. As a result, they end up only including that single idea in their summary, neglecting to cover the text’s other major points. Instead, if you’re asked to write a 3-4 sentence summary, you should think about how to divide up the text’s primary ideas somewhat proportionately across the remaining 2-3 sentences after your opening sentence.

The goal is to provide a balanced, representative summary that captures the essence of the text, not just the parts that stood out the most to you personally. Maintaining this sense of proportion is key to crafting an effective, comprehensive summary that meets the expectations of your audience. To illustrate, here is an expanded version of the first example; you can read the full original article here to compare: https://harpers.org/archive/1932/10/in-praise-of-idleness/

In the 1932 article “In Praise of Idleness” from The Atlantic, philosopher Bertrand Russell argues that Western society puts too much emphasis on work and productivity, and that we would be better off if we valued leisure more. First, Russell notes that advances in technology have greatly increased productivity, which should have allowed everyone to work less; instead, though, companies will lay off employees while requiring those who remain to work the same hours as they did before. He argues that the same productivity could be achieved by halving the number of hours that people must work while doubling the number of employees, in which case everyone would be happier, as everyone would have both income and free time. He also critiques the notion that work is inherently valuable or meaningful, pointing out that this argument is most commonly made by the idle rich to make the poor feel better about their lot. Finally, Russell argues that with more leisure time and less exhaustion from work, people will be more free to pursue education, develop hobbies, and enjoy their communities.

A Note about Attributive Tags

Attributive tags, sometimes also called “signal phrases,” are how you indicate in your writing that you are referring to someone else’s words or ideas. The most typical type of attributive tag in academic writing comes at the beginning of a sentence and consists of an author’s last name and a verb, as in:

- Russell argues

- Kahneman explains

- Rosenfield criticizes

The Names

A standard practice is to identify an author’s full name the first time you introduce them/their source in your essay. After that, use only the last name. In academic writing, we never refer to people by first name only, and we typically also do not include titles like Dr., Mr., or Ms.

When you have a source with two authors, you will use both names. As in the example opening sentence above, you’ll use both full names the first time, and then both last names the rest of the time, as in:

- Hartogsohn and Vudka explain

- Hartogsohn and Vudka describe

Notice that the order of the names is always the same!

Finally, if you have a source with more than two authors, you will use the first author’s name, and then the abbreviate et al. (which stands for “and others”). Again, you’ll use the full name plus et al. the first time, and then just the last name plus et al. the rest of the time:

- First reference: In the Journal of Management article “Generational Differences in Work Values: Leisure and Extrinsic Values Increasing, Social and Intrinsic Values Decreasing,” Jean M. Twenge et al. describe their study finding that younger generations care more about leisure time and expect more compensation than older generations.

- After the first reference:

- Twenge et al. discuss

- Twenge et al. suggest

When the context makes it clear that you are referring to a source you have previously named, you can use pronouns or other replacements to avoid repeating the names over and over:

- Russell argues . . . . He notes that . . . .

- Rosenfield criticizes . . . . She claims that . . . .

- Hartogsohn and Vudka explain . . . . They describe . . . .

- Twenge et al. discuss . . . . The researchers suggest that . . . .

The Verbs

When you’re writing about books, articles, or other texts in academic work, you’ll notice we mostly use present tense, even when we’re describing old texts. The idea is that the content of written work exists in an eternal present – the words on the page remain unchanged regardless of when they were written. It can get a little trickier when you’re summarizing, for example, a study that was conducted. In cases like that, you might use past tense when referring to the actions the researchers took, but still use present tense when summarizing the ideas in the text. Notice in this example that the middle sentences, which describe the study itself, is in past tense, while the rest of the summary uses present tense.

In the Journal of Management article “Generational Differences in Work Values: Leisure and Extrinsic Values Increasing, Social and Intrinsic Values Decreasing,” Jean M. Twenge et al. describe their study finding that Millennials care more about leisure time than previous generations. The researchers analyzed data that was collected from high school seniors in 1976 (Boomers), 1991 (GenX), and 2006 (Millennials), comparing the value each cohort placed on leisure time, intrinsic rewards (interesting or fun work), extrinsic rewards (money and prestige), altruistic rewards (helping others), and social rewards (connectedness) when it came to their career goals. They found that desire for leisure time increased across the three generations, desire for intrinsic, altruistic, and social rewards decreased across the generations, and desire for extrinsic rewards spiked with GenX and then dropped slightly with Millennials, though it remains much higher than it was with Boomers. Twenge et al. argue that employers could most effectively attract younger employees by offering more vacation time and more flexible schedules. They also note that their data supports the stereotype that Millennials are entitled and overconfident, expecting more status and compensation than is realistic.

Also, try to avoid saying things like “the author says” or “talks about” – they’re a bit too vague, plus some picky professors might point out that written works don’t actually “say” or “talk” about anything! Instead, you can use more specific verbs like:

- argues

- demonstrates

- illustrates

- analyzes

- explains

- presents

- contends

- examines

These verbs do a better job of indicating what authors are doing, and they sound more academic. Just make sure you pick one that makes sense in your context.

Response Writing

Responses build on summaries by adding your own opinions about the text. A response essay is a common early college writing assignment because response essays demonstrate that students know how to read with a critical eye. However, they can be challenging for students who have only ever been asked to regurgitate information and not expected (or even allowed!) to share their own views. When they are done well, though, responses are a great way for students to demonstrate that they can not only read well enough to summarize a text, but they can move to those higher levels in Bloom’s taxonomy by analyzing how the text works and evaluating its effectiveness.

Response essays typically do some combination of the following:

- Critique the ideas or arguments made in the text by analyzing and evaluating the text’s logic and evidence

- Critique the way the text is written by analyzing and evaluating the text’s broader rhetorical effectiveness

- Critique the significance of the text, to yourself and/or to others

Your instructor may ask you to focus on just one of those, but most commonly, all three aspects of the response are fair game. The following sections explain what each of these response types focuses on and provide lists of questions to help you develop ideas.

Critiquing a Text’s Ideas

One type of response focuses solely on the text’s content (what it says). You might use this list of questions to generate critiques of a text’s ideas:

- What is the central claim or argument being made by the author? Can you summarize the main point in a single sentence? How clear, focused, and specific is the claim being made?

- What evidence (e.g. facts, data, examples, expert opinions) does the author use to support their argument? Is the evidence credible, relevant, and sufficient to support the claims made?

- How well does the author’s logic and reasoning hold up under scrutiny? Are there any flaws, inconsistencies, or gaps in their argumentation?

- Where does the text acknowledge or address counterarguments or alternative viewpoints? How effectively does the author respond to potential objections to their position?

- What assumptions does the author rely on? Are these assumptions justified and warranted?

- Based on your analysis, what is your overall assessment of the text? Do you find the author’s argument convincing and well-supported, or do you have significant reservations or criticisms?

Critiquing a Text’s Rhetorical Effectiveness

A text’s logic and evidence are just one aspect of its rhetorical effectiveness. You could broaden your critique by examining other aspects of how the text is written. For more on rhetorical theory, see the chapter titled “Classical Rhetorical Theory.” For a start, though, you might use this list of questions to generate critiques of a text’s rhetoric:

- Who is the intended audience for this text, and how does the author seem to be addressing or appealing to them?

- How effectively does the author anticipate and respond to potential counterarguments or objections from the audience?

- How effectively has the author adapted the language, tone, and level of technicality for the intended audience?

- What is the genre of the text? How well does the text follow the conventions of the genre? If it deviates from them, how do those choices impact the text’s effectiveness?

- What qualifications, expertise, or authority does the author have on this topic? How effectively does the author convey these in the text?

- How does the author establish their credibility and trustworthiness?

- What are the potential biases or conflicts of interest that could undermine the author’s credibility? Do you see evidence of these in the text?

- What strategies does the author use to get the audience to feel invested in the topic? How effective are these strategies?

- How effectively does the author connect their ideas to their intended audience’s values?

- What emotions does the author try to evoke in the reader? Are the emotional appeals appropriate and justified given the context and subject matter?

- How effectively does the author use language, tone, imagery, and other rhetorical devices to elicit emotional responses?

- What is the overall tone of the text (e.g. formal, informal, conversational, academic, passionate)? How effective is this tone for the subject matter and the intended audience?

- How effectively does the author use word choice and sentence structure to develop the text’s style and voice?

- How is the text structured and organized (e.g. chronological, compare-contrast, problem-solution)? Does the organization and flow of ideas help or hinder the effectiveness of the author’s arguments? Are there clear transitions and logical connections between the different sections and points made in the text?

- What specific rhetorical devices (e.g. metaphors, analogies, repetition, rhetorical questions) does the author use, and how do they impact the effectiveness of the text? Are these devices used judiciously and in service of the author’s overall argumentative goals?

- Overall, how successful is the text in achieving its intended purpose for its intended audience? What are the key strengths and weaknesses of the text’s rhetorical appeals and stylistic choices? What recommendations would you make to the author to improve the overall effectiveness of the text?

Critiquing a Text’s Significance

Another angle you could take is to analyze and critique the overall impact or significance of the text. This can be personal, focused just on what the text means to you, or could take a larger view and address how the text fits in its broader social context. You might use this list of questions to generate critiques of a text’s significance:

- How does the text resonate with your own experiences, beliefs, or worldview? In what ways does it connect to or challenge your personal perspective?

- What emotions, memories, or associations does the text evoke for you on a personal level? How do these personal responses shape your interpretation and evaluation of the text?

- In what ways does the text illuminate or expand your understanding of yourself, your relationships, or your place in the world? How might it inspire personal growth, reflection, or transformation?

- Are there particular ideas or passages in the text that you find especially compelling, relatable, or meaningful on a personal level? What is it about these elements that resonates with you?

- How does your own social, cultural, or demographic background influence how you engage with and make sense of the text on a personal level? In what ways might your personal identity and experiences shape your critique?

- How relevant and significant is the argument in the broader context? Does it address an important issue, and does it offer new or meaningful insights?

- What broader social, cultural, political, or historical issues, themes, or debates does the text engage with or illuminate? How does it contribute to your understanding of these larger social contexts?

- In what ways does the text reflect, challenge, or reshape common social narratives, assumptions, or power dynamics? How might it impact societal attitudes, beliefs, or behaviors?

- Who are the key stakeholders, communities, or social groups that the text centers? Whose perspectives and experiences are not represented?

- How might the text’s themes, messages, or representations impact different groups in different ways?

- What are the broader societal implications or real-world consequences – positive or negative – that could stem from the ideas, arguments, or perspectives presented in the text?

Conclusion

Reading and writing at the college level requires moving beyond simply absorbing information to critically engaging with texts. By applying strategies like annotating, summarizing, and responding, you can develop the higher-order cognitive skills of analysis, evaluation, and creation from Bloom’s taxonomy. Mastering these skills allows you to thoughtfully assess the strengths, weaknesses, and potential impacts of different texts. Ultimately, the ability to read critically and respond substantively demonstrates an essential intellectual skillset. It shows you can think deeply, reason rigorously, and communicate insightfully about complex ideas. Honing this expertise will serve you well not just in college, but in navigating our increasingly information-saturated world with discernment and insight.

Related Writing Projects

- Response Essay

- Rhetorical Analysis Essay – One Text

- Rhetorical Analysis Essay – Compare and Contrast Two Texts

Works Cited

Hartogsohn, Ido, and Amir Vudka. “Technology and Addiction: What Drugs Can Teach Us about Digital Media.” Transcultural Psychiatry, vol. 60, no. 4, 2023, pp. 651-661, https://doi.org/10.1177/13634615221105116.

Kahneman, Daniel. Thinking, Fast and Slow. Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2011.

Rosenfield, Kat. “True Crime Distorts the Truth about Crime.” Reason, Oct. 2023, pp. 58-62.

Russell, Bertrand. “In Praise of Idleness.” Harper’s Magazine, Oct. 1932, harpers.org/archive/1932/10/in-praise-of-idleness/.