3 Classical Rhetorical Theory

The word “rhetoric” is often used pejoratively to mean “empty words” or “manipulative argumentation,” but as someone who studies rhetoric, I find this usage a little insulting and far too narrow. I like Kenneth Burke’s definition of rhetoric as “a symbolic means of inducing cooperation in beings that by nature respond to symbols.” Burke’s definition is a little harder to understand, so let’s break it down:

- “A symbolic means” = using symbols, which would include words but also all kinds of other symbols

- “Of inducing cooperation” = getting someone to do what you want, whether that’s to believe something, react a certain way, or change their behavior

- “Beings that by nature respond to symbols” = humans (and possibly other animals, though we’re going to focus on human-to-human interactions for this textbook!)

In other words, according to Burke, rhetoric is the use of words and/or other symbols to get influence other people’s beliefs or behaviors. That would certainly include manipulative argumentation, but it would also include telling a joke that makes someone laugh, asking someone to pass the salt at the dinner table, and even giving the weather forecast (assuming the forecaster wants the audience to believe it). It would also include non-verbal symbolic communication, like wearing a suit to show a job interviewer that you’re professional or responding to a text with the appropriate emoji to convey your emotional reaction. Rhetoric is, therefore, an enormous field of study! Those of us who study rhetoric also have a tendency to think of everything that has any symbolic meaning as a “text” that can be read and every communication as a kind of “argument,” because communication always comes with the purpose of changing something in the audience.

Even though rhetoric as a field has grown to encompass all kinds of symbolic communication, the study of rhetoric has its origins in ancient Greece. The earliest known theorists of rhetoric were teachers called “Sophists” who instructed students in the art of persuasive public speaking. Prominent Sophists like Gorgias and Protagoras emphasized the power of language to shape public opinion and sway audiences. These skills were particularly important in a democratic culture where decisions were often made on the basis of arguments presented by politicians. Following the Sophists, many Greek philosophers developed their own rhetorical theories. Aristotle, in fact, was the philosopher who established what is now called “the Rhetorical Triangle,” which you’ll see more about below.

The rhetorical theories that originated in ancient Greece have been studied, refined, and expanded upon ever since, and they continue to be relevant today. We can use these ideas to evaluate the work of others and to help us develop our own work.

The Rhetorical Triangle

The rhetorical triangle is a way of analyzing a text’s power by looking at three interrelated concepts: logos, ethos, and pathos.

Logos

Logos refers to the logic of a text. It includes everything from how clear and consistent the message is to the strength of the evidence. The ways a text develops and supports its message are its logical appeals. Here are some questions you could use to analyze the logos in a text:

- Is the message or main idea clearly stated and easy to follow?

- Are there any logical fallacies or contradictions in the reasoning?

- Is the evidence provided relevant, credible, and sufficient to support the claims?

- Are counterarguments fairly considered and addressed?

- Does the conclusion logically follow from the premises stated?

- Are there gaps, assumptions, or oversimplifications in the logic?

Logical fallacies are errors in reasoning that can undermine an argument’s validity. Some common fallacies include:

- Ad hominem: Attacking the person making the argument rather than addressing the argument itself.

- “You can’t trust Dr. Smith’s research on climate change because he drives a gas-guzzling SUV.”

- “Why should we listen to Professor Lee’s economic theory? She’s never even run a business.”

- “The defendant’s testimony isn’t credible because he has a criminal record.”

- Straw man: Misrepresenting an opponent’s argument to make it easier to attack.

- Person A: “I think we need stricter gun control laws.” Person B: “You just want to take away everyone’s guns and leave us defenseless!”

- Person A: “Schools should offer vegetarian options in cafeterias.” Person B: “So you’re saying we should force all kids to become vegans?”

- Person A: “We should increase funding for public transportation.” Person B: “Oh, so you want to ban all cars and make everyone ride the bus?”

- False dichotomy: Presenting only two options when there are actually more.

- “Either we cut social programs, or we’ll go bankrupt as a nation.”

- “America: love it or leave it.”

- Slippery slope: Arguing that a small step will inevitably lead to a chain of related events.

- “If we ban assault weapons, soon they’ll take away all our guns, and then we’ll be defenseless against a tyrannical government.”

- “If we allow students to use calculators in math class, they’ll never learn how to do basic arithmetic.”

- “If we increase the minimum wage, companies will have to raise prices so much that no one will be able to afford anything.”

- Circular reasoning: Using the conclusion as a premise to support itself.

- “The Bible is true because it says so in the Bible.”

- “Freedom of speech is important because we should be able to speak freely.”

A logical argument should be structured with clear premises that lead to a supported conclusion. It should use valid reasoning, avoid fallacies, and be based on credible evidence. Good arguments also anticipate and address potential counterarguments.

In conclusion, logos is crucial for building a strong, persuasive argument. By using clear reasoning, solid evidence, and avoiding logical fallacies, writers can create compelling cases that appeal to their audience’s intellect and critical thinking skills. However, logos alone is often not enough to fully persuade an audience, which is why it’s important to consider ethos and pathos as well.

Ethos

Ethos refers to the character of the writer, in particular, how that writer’s character comes across through the text. In most cases, we are more likely to believe a writer who seems to be trustworthy, credible, sensible, and knowledgeable. The ways a text portrays the persona of the author are its ethical appeals. (That terminology often confuses students, because we think of the word “ethical” as referring to morality.)

Here are some questions you could use to analyze ethos in a text:

- What credentials, expertise, or firsthand experience does the writer demonstrate regarding the topic?

- Does the writer come across as fair, unbiased, and level-headed?

- Is the tone reasonable, respectful, and mature?

- Does the writer establish common ground and good will with the audience?

- Are there instances where the writer’s credibility or objectivity is undermined?

- Does the writer fully disclose biases, vested interests, or limitations in their perspective?

Closely related to ethos is the concept of angle of vision, which can also be called perspective or point of view. Different people have different perspectives on a topic, which significantly influences how they think and write about it. For example, a teacher and a student might have very different views on the effectiveness of a particular teaching method. Even a single person can have multiple perspectives based on their various roles in life. A parent who is also a teacher might approach an educational issue differently depending on which role they prioritize. A few questions to analyze angle of vision might be:

- How closely involved is the author with the issue? Are they writing as someone with a direct interest in this problem, or are they more of an outside observer?

- To what extent does the author draw on past experience? How would those past experiences influence their ideas about the topic?

- What is the author’s reason to care about this issue? What is at stake for the author?

- What values and beliefs seem to shape the author’s perspective on this topic?

- What relationship does the author have (or want to have) with the audience?

You might notice that a lot of the questions regarding angle of vision may also lead you to identify the author’s potential biases. It’s important to recognize that everyone has some form of bias. Biases are simply the ways our own angles of vision may limit our ability to fully recognize, understand, or respect other perspectives. The term “bias” often carries a negative connotation, but it can be oversimplifying to assume there’s such a thing as a purely objective point of view. Instead of striving for complete objectivity, which is arguably impossible, writers should aim for transparency about their perspective and potential biases. This honesty can actually enhance their ethos by demonstrating self-awareness and fairness.

In conclusion, ethos is about establishing credibility and trust with the audience. By demonstrating expertise, fairness, and transparency about one’s perspective, a writer can build a strong ethical appeal. This not only makes the audience more likely to listen but also creates a foundation of respect and understanding, even if the reader ultimately disagrees with the argument.

Pathos

Pathos refers to how effectively the text appeals to the audience’s values and emotions. A good argument needs to make the audience care about the issue, and perhaps even make the audience feel some sympathy for the writer. The ways a text stimulates the audience’s emotions are its pathetic appeals (or emotional appeals, now that the word “pathetic” has shifted in meaning). Here are some questions you could use to analyze pathos in a text:

- Does the writing tap into shared values, hopes, fears, or identities of the audience?

- Are personal anecdotes, examples or hypotheticals used to stir emotions?

- Is wording used deliberately to evoke specific emotional responses (such as outrage, sympathy, or inspiration)?

- Is the audience’s self-interest or aspirations effectively engaged?

- Does the emotional angle risk being perceived as manipulation or oversimplification?

The importance of appealing to audience needs, values, and motivations cannot be overstated in effective communication. By understanding and addressing what matters to your audience, you can create a connection that goes beyond mere logical persuasion. This doesn’t mean simply telling people what they want to hear, but rather framing your argument in a way that resonates with their existing beliefs and concerns.

It’s crucial to note that pathos isn’t just about evoking obvious or extreme emotions. While many people might immediately think of appeals to pathos as using pictures of sad puppies or stirring up anger, any emotion can be part of a pathetic appeal. This includes positive emotions like hope, pride, or excitement. For example, a speech about environmental conservation might appeal to fear by discussing the dangers of climate change, but it could also appeal to hope and inspiration by highlighting successful conservation efforts and the beauty of nature.

Ultimately, pathos is about connecting with your audience on an emotional level. By appealing to shared values, using vivid language and examples, and evoking appropriate emotions, writers can make their arguments more compelling and memorable. However, it’s important to use pathos responsibly and in balance with logos and ethos. Overreliance on emotional appeals without logical backing or credibility can be perceived as manipulation, potentially undermining the overall argument.

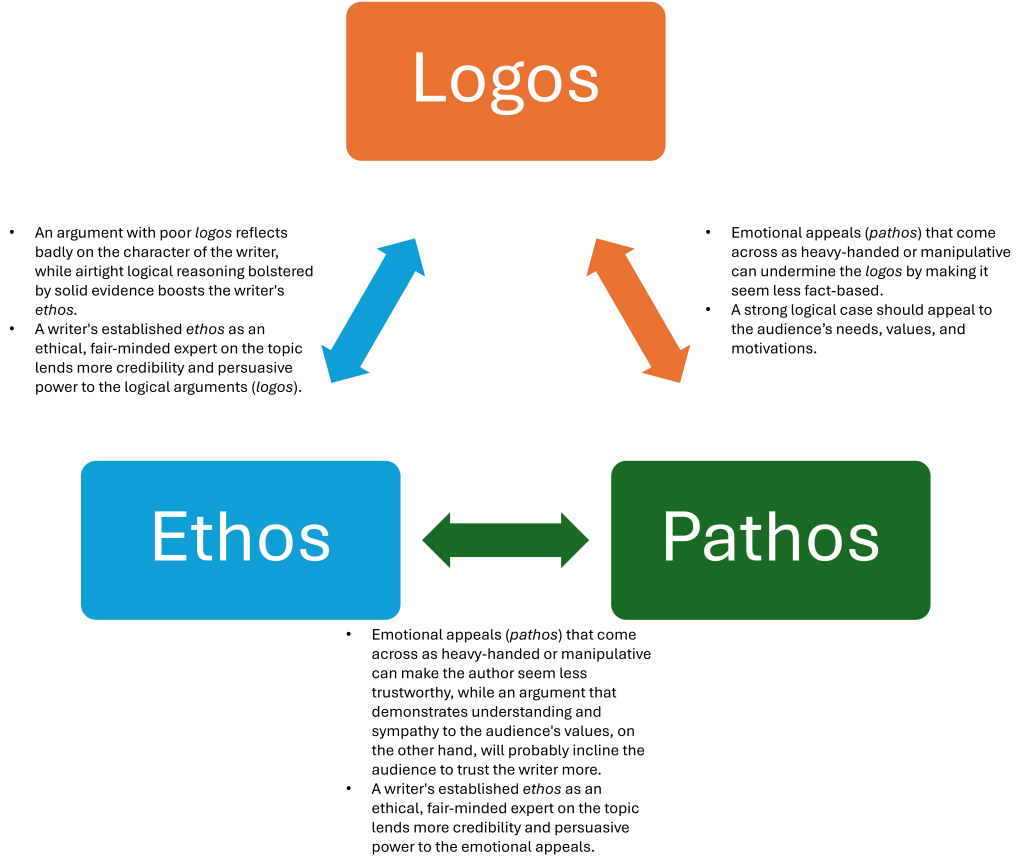

The Interconnected Triangle

Clearly, these three rhetorical factors also influence each other in a variety of ways. For example, an argument with poor logos (unclear, contradictory, fallacious, or lacking in evidence) reflects badly on the character of the writer, thus indirectly harming the writer’s ethos. Audiences will question the writer’s expertise, trustworthiness, and intellectual honesty if the reasoning is sloppy or unsupported. Conversely, valid logical reasoning bolstered by solid evidence boosts the writer’s ethos as someone knowledgeable who argues in good faith. Emotional appeals (pathos) that come across as heavy-handed, manipulative, or playing too much on fears/insecurities rather than positive values can undermine the logos by making the argument feel less fact-based, and if audiences feel like the author is trying to manipulate them, they may start to question the author’s ethos. An argument that demonstrates understanding and sympathy to the audience’s values, on the other hand, will probably incline the audience to trust the writer more. A writer who comes across as biased and unreasonable (bad ethos) is going to encourage the audience to be more skeptical of their logos, while on the flip side, a writer’s established ethos as an ethical, fair-minded expert on the topic lends more credibility and persuasive power to both the logical arguments (logos) and emotional appeals (pathos) employed.

Conclusion

The key elements of classical rhetorical theory provide a valuable framework for both analyzing and crafting persuasive arguments. As you analyze the rhetorical strengths and weaknesses of arguments across texts, you will develop a more nuanced ability to assess logos, ethos, and pathos. Applying these skills will empower you to engage with complex issues as critical thinkers and ethical communicators – discerning “what persuades” beyond just surface appeals. By becoming more consciously aware of these features, you will also better be able to employ them thoughtfully and purposefully in your own work.