12 The Toulmin Model of Argumentation

Toulmin: An Overview

The Toulmin model, which was developed in the 1950s by philosopher Stephen Toulmin, is a tool that allows you to identify the necessary parts of an argument. It helps you plan your argument by ensuring you have all the required components. It also enables you to analyze other people’s arguments and pinpoint their strengths and weaknesses.

Claim

The main part of an argument is the claim, which is the central assertion being made. A claim must be disputable and cannot be a fact or something the audience already accepts.

There are three types of claim:

- Claims of fact – assertions about what is, what was, or what will be

- Claims of value – assertions about what is good or bad, right or wrong

- Claims of policy – assertions about what should or should not be done

The claim is the core of the thesis statement. You can also think of the thesis statement as the exact wording you’ve chosen to express the claim, whereas the claim is the actual idea being conveyed. Each of the claim types listed above has its own chapter with much more information and examples.

The Hierarchy of Claim Types

The order in which these types of claims are presented – fact, then value, then policy – is not arbitrary. We can’t make arguments of value without relying on facts, and we can’t make arguments of policy without relying on arguments of value (which rely on facts). In other words, we first have to agree about what reality is before we can even argue about whether it’s good or bad. Then we have to agree about what is good or bad before we can effectively propose changes to make things better. Understanding this nested structure of argument types can be incredibly helpful when we think about some of the most intractable arguments in our society, over topics like gun control or abortion. Often, people jump straight to arguments of policy or value, when the problem is that they don’t even agree on the same basic facts, like whether the 2nd Amendment covers automatic weapons or whether a fetus is a person. We are sometimes very bad at identifying the real topos of our arguments!

On less controversial topics, the hierarchy is often less important because the underlying facts and values may already be widely accepted by the audience. You’ll notice these when you read further in this chapter and learn about warrants.

Reasons

Reasons are assertions made in support of claims. An argument will have one claim, but it will usually have multiple reasons. Reasons may or may not be accepted facts, but usually they’re not; usually they themselves are arguable assertions. You can often find the reasons that support your claim by just filling in the blank after “because” following your claim.

Enthymemes & Warrants

When you connect each reason to the claim with a word like “because” or “therefore,” it creates a logical structure called an enthymeme. Consider the following pair of statements:

- Cats are good pets.

- Cats are low maintenance.

Separately, each sentence is a claim that can be supported. However, think about how that changes when I draw a logical connection between the two statements:

- Cats are low maintenance; therefore, cats are good pets. OR

- Cats are low maintenance, so cats are good pets. OR

- Cats are good pets because cats are low maintenance.

This new statement is doing something more than just the two statements individually. The “because” or “therefore” or “so” is doing a lot of work by establishing a logical relationship between the two statements in which one of the statements is a reason or explanation for the other. Two statements in this kind of relationship are an enthymeme.

The enthymeme is an incomplete logical structure because it always assumes that a third, often unstated, assertion is true.

Let’s examine some examples:

- Enthymeme: Cats are good pets because cats are low maintenance.

- Assumption: It’s good for a pet to be low maintenance.

- Enthymeme: Cats are good pets because cats are clean.

- Assumption: It’s good for a pet to be clean.

This assumption, in Toulmin terminology, is called a warrant. Recognizing and perhaps defending this assumption is essential to ensuring your argument is complete and sound.

Often, it’s easier to understand the significance of warrants when you see enthymemes that don’t make logical sense. For example:

- Enthymeme: Cats are good pets because cats destroy your furniture.

- Warrant: It’s good for a pet to destroy your furniture.

Read as two independent sentences, the claim “Cats are good pets” and the reason “Cats destroy your furniture” are fine. I can believe both are true, and there’s nothing weird about that, really. However, as soon as I connect them with that word “because,” something happens. I’m creating a relationship between these two statements, and the believability of that relationship depends on something else being true. Suddenly, I have gone from being a person who likes cats despite the fact that they destroy furniture to being a person who likes cats because they destroy furniture, and that’s a little bit odd.

In real life arguments, we often don’t give a second thought to these assumptions because, like in the first two examples, they may not be particularly controversial. However, it’s really valuable to be able to identify what they are. Alongside the reasons, they are the pillars on which the argument rests, and even when they’re not extremely controversial, some critical thinking about them can help us accomplish two tasks: (1) providing more thorough evidence for our argument and (2) responding more effectively to opposing views.

Warrants, like claims, can be classified into different types, and they’re based on the type of assumption being made.

- Substantive warrants – assumptions about how to interpret evidence

- Authoritative warrants – assumptions about who is trustworthy or credible

- Motivational warrants – assumptions about what is good or bad, desirable or undesirable, right or wrong

Note that all of the examples above consist of motivational warrants. You can find much more on warrants, including the other two types, in the chapters on writing arguments of fact and arguments of evaluation.

Grounds & Backing

Grounds are the evidence or explanation that support the reasons; the grounds show your audience why they should believe or agree with your stated reason. Similarly, warrants often need support, and this support is called backing. The backing shows your audience why they should believe or agree with your warrant. Exactly what the grounds and backing consist of can vary quite a bit depending on the specifics of the argument, but here are some questions that may help you develop these. Be sure to ask the questions for each reason and for each warrant!

- What exactly do I mean by this?

- How do I know that this is true?

- Why is this true?

- What are some examples to show that this is true?

You may not have answers to each question every single time, but generally, the more you have, the better!

What Is Evidence?

For both grounds and backing, there are many types of evidence that you can use. When you’re developing an argument, you may find it helpful to brainstorm possibilities from as many different categories of evidence as you can; this exercise often leads to the discovery of evidence that you might not otherwise have considered.

Types of evidence include:

- Personal experience

- Observation/anecdote

- Primary research data

- Secondary research data

- Hypothetical examples

- Logical reasoning

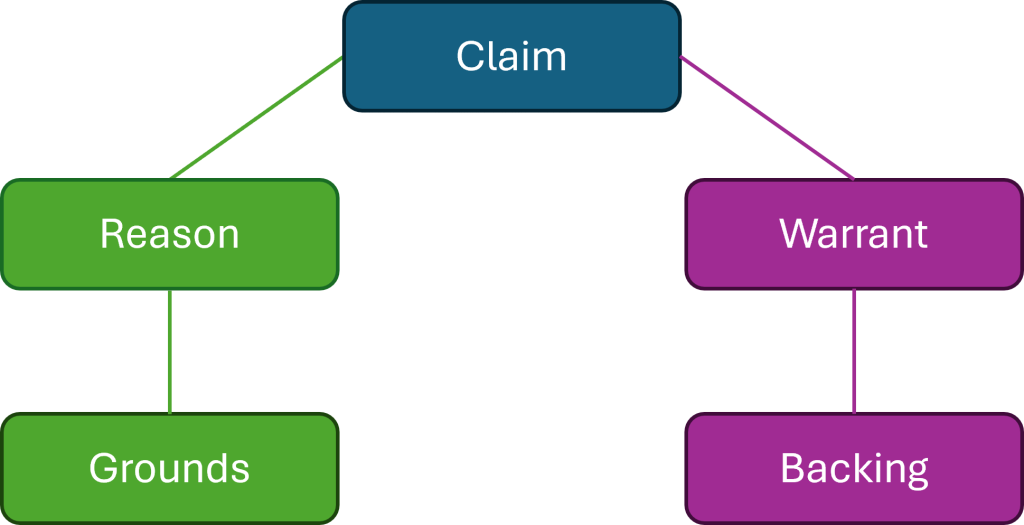

The Primary Triad

Sometimes the claim, reason and grounds, and warrant and backing, are called the “primary triad.” They function as the core of any line of argument. You can think of the reason and grounds together as one “leg” of support for the claim, while the warrant and backing together are the other “leg.”

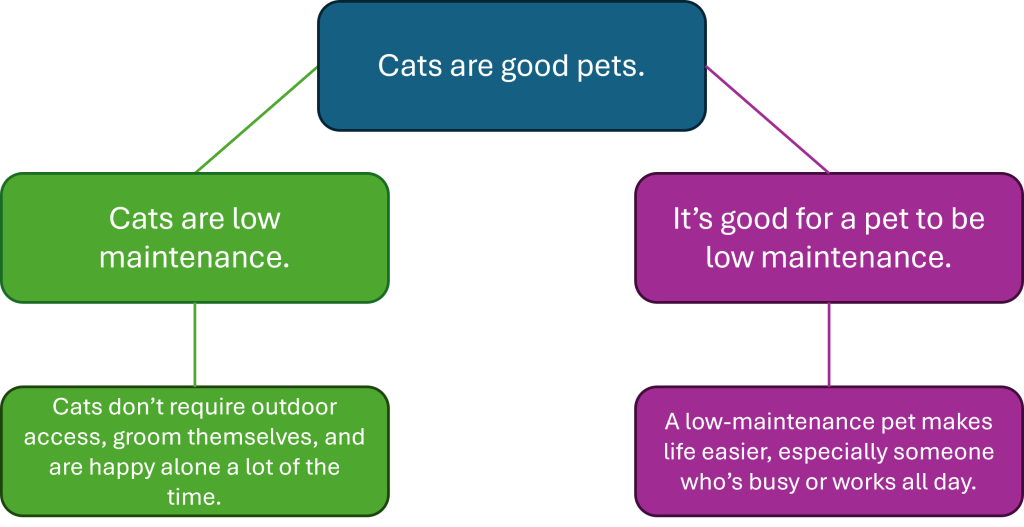

Here is the primary triad using our example enthymeme:

Note that the grounds and backing in this example are pretty underdeveloped! A strong argument would provide much more information and explanation to in both of these areas.

Conditions of Rebuttal & Responses to Conditions of Rebuttal

The next aspect to consider in the Toulmin model are the conditions of rebuttal. Toulmin emphasizes first identifying all of the potential objections to the reason and grounds, as well as all of the potential objections to the warrant and backing. While you could brainstorm other objections beyond the conditions of rebuttal that challenge the argument more holistically, Toulmin’s framework focuses primarily on why an audience might disagree with the reason itself, distrust the grounds supporting the reason, disagree with the warrant itself, or distrust the backing for the warrant. In other words, the conditions of rebuttal are targeted to specific lines of argument, not necessarily to the overall claim.

To illustrate, consider the earlier argument that “Cats are good pets because cats are low maintenance.” Potential rebuttals include someone arguing that cats are not actually low-maintenance (rebutting the reason) and someone arguing that it’s not important for a pet to be low maintenance (rebutting the warrant). “Cats are not good pets” is NOT a condition of rebuttal because it’s challenging the claim itself rather than the reason or warrant.

After you have examined your lines of argument and identified all of the potential objections, you must then respond to those objections, particularly if they have any validity at all. Sometimes students forget to do this part! It’s great to acknowledge where there are valid objections to your argument, but you shouldn’t just abandon your argument after doing so. If you still believe you’re right (and hopefully you do), you need to explain why you think these objections are either incorrect or not significant enough to make you change your mind.

There are two main strategies for responding: concession and refutation. With concession, the writer grants a reasonable point made by the opposition, e.g. “It is true not all cats are utterly low-maintenance,” but then reaffirms their overall claim, e.g. “However, compared to most typical pets, they require substantially less care.” Alternatively, with refutation, the writer respectfully presents an opposing view, e.g. “Some argue cats are not low-maintenance because…,” but then demonstrates why this view is mistaken with counterevidence.

You do not need to refute every objection; judicious concessions can actually strengthen an argument by enhancing your ethos and displaying fairness in considering other perspectives. As long as concessions are followed by reaffirmation of the central claim, the overall argument remains sound.

In identifying the conditions of rebuttal, you may notice that warrants are often values widely shared by the audience but prioritized differently. Consider the enthymeme, “The government should ban plastic bags because plastic bags are bad for the environment.” The warrant, “The government should enact policies to protect the environment” may not itself be problematic for the audience. However, some may prioritize other concerns above environmental protection; for example, they may agree both with the reason (plastic bags are bad for the environment) and the warrant (the government should enact policies to protect the environment), but they might argue that banning plastic bags would be an inefficient policy, and that the inefficiencies outweigh the potential benefits. In this case, you would need to anticipate what these competing values might be, understand their basis, and make a case for why the value underlying your own argument should be prioritized.

Qualifiers

The last Toulmin element is the term qualifier, and these bring us all the way back around to our claim. Qualifiers are words or phrases that limit the scope of your claim. Often, you’ll come to these as you have brainstormed your conditions of rebuttal. You’ll realize there are some areas where you need to allow for exceptions. You might adjust your claim by adding limiting words like “often,” “generally,” “usually,” etc. I might change my “Cats are good pets” claim to something like “Cats are generally good pets.” This way I’m not saying all cats are always good pets. Perhaps I change it to something like, “Cats are good pets for most people,” to acknowledge that some people might have specific needs that cats don’t meet. You have to be careful with qualifiers because you can qualify your claims so much that you’re no longer making an argument. If you find that your claim is essentially just saying that something may be true, you might not even have an arguable claim anymore. You’ll want to consider carefully what exceptions are absolutely necessary for you to allow.

Line of Argument

Each reason with all of its attendant parts – the warrant, the grounds, the backing, the conditions of rebuttal, the responses to the conditions of rebuttal – is a line of argument. A claim is typically supported with multiple lines of argument, and it’s important that all of your lines of argument are well-developed.

If you put all of the “Cats are good pets because cats are low-maintenance” pieces together, here is what that line of argument might say:

Complete Example Line of Argument

Claim (with qualifier): Cats are good pets for most people.

Reason: Cats are low maintenance.

Grounds: Unlike dogs, cats do not need to be walked multiple times daily or require constant supervision. Unlike other common pets like fish, birds, rodents, or reptiles, they require very little specialized equipment or supplies. They naturally use litter boxes without extensive training, groom themselves regularly, and can be left alone for extended periods without experiencing separation anxiety. My personal experience having owned a dog, cats, fish, gerbils, birds, and even a tree frog confirms that cats require significantly less daily intervention and care than other pets. With the use of a timed feeder and automatic litter box, I have even left my cats alone while traveling for a couple of days, something that simply would not be possible with any of these other pets.

Warrant: It’s desirable for a pet to be low maintenance.

Backing: Modern lifestyles often involve long work hours, frequent travel, and busy schedules that make high-maintenance pets impractical. Low-maintenance pets allow people to enjoy companionship without overwhelming time commitments or lifestyle restrictions. Additionally, lower maintenance means less stress for both pet and owner.

Conditions of Rebuttal against the Reason: Some might argue that cats are not actually low-maintenance, pointing to litter box cleaning, regular feeding schedules, and occasional health issues.

Response to Conditions of Rebuttal against the Reason: While it’s true that cats do require daily litter box maintenance and regular feeding, these tasks are minimal compared to the extensive daily care required by many other pets. A litter box takes minutes to clean, whereas dogs require multiple lengthy walks regardless of weather or owner schedule, and cleaning up after pets who live in cages or terrariums is even more time-consuming and difficult.

Conditions of Rebuttal against the Warrant: Others might contend that being low-maintenance is not necessarily a positive trait in pets, arguing that the care and attention required by pets is part of the rewarding relationship.

Response to Conditions of Rebuttal against the Warrant: Regarding the argument that low maintenance diminishes the pet-owner relationship, this fundamentally misunderstands what makes pet relationships meaningful. The bond between cats and their owners develops through affection, play, and companionship, none of which happen naturally as a part of any other pet care with the possible exception of walking a dog. I find that my cats are wonderful and affectionate companions because I take time to play with them and pet them.

In Paragraph Form

One reason cats are good pets for most people is that cats are low maintenance. Unlike dogs, cats do not need to be walked multiple times daily or require constant supervision. Unlike other common pets like fish, birds, rodents, or reptiles, they require very little specialized equipment or supplies. They naturally use litter boxes without extensive training, groom themselves regularly, and can be left alone for extended periods without experiencing separation anxiety. My personal experience having owned a dog, cats, fish, gerbils, birds, and even a tree frog confirms that cats require significantly less daily intervention and care than other pets. With the use of a timed feeder and automatic litter box, I have even left my cats alone while traveling for a couple of days, something that simply would not be possible with any of these other pets. It’s desirable for a pet to be low maintenance because modern lifestyles often involve long work hours, frequent travel, and busy schedules that make high-maintenance pets impractical. Low-maintenance pets allow people to enjoy companionship without overwhelming time commitments or lifestyle restrictions. Additionally, lower maintenance means less stress for both pet and owner. Some might argue that cats are not actually low-maintenance, pointing to litter box cleaning, regular feeding schedules, and occasional health issues. While it’s true that cats do require daily litter box maintenance and regular feeding, these tasks are minimal compared to the extensive daily care required by many other pets. A litter box takes minutes to clean, whereas dogs require multiple lengthy walks regardless of weather or owner schedule, and cleaning up after pets who live in cages or terrariums is even more time-consuming and difficult. Others might contend that being low-maintenance is not necessarily a positive trait in pets, arguing that the care and attention required by pets is part of the rewarding relationship. However, this fundamentally misunderstands what makes pet relationships meaningful. The bond between cats and their owners develops through affection, play, and companionship, none of which happen naturally as a part of any other pet care with the possible exception of walking a dog. I find that my cats are wonderful and affectionate companions because I take time to play with them and pet them.