Chapter 9: The Society of Orders

The eighteenth century was the (last) great century of monarchical power and the aristocratic control of society in Europe. It was also the end of the early modern period, before industrialism and revolution marked the beginning of the modern period at the end of the century. Ironically, the enormous changes that happened at the end of the century were totally unanticipated at the time. No one, even the most radical political philosopher, believed that the political order or the basic technological level of their society would be fundamentally changed.

One example of that outlook is that of a philosopher and writer, Louis-Sébastien Mercier, who in 1781 published The Painting of Paris, which depicted a more orderly and perfect French society of the future. In the Paris of the future, an enlightened king oversees a rationally governed society and extends personal audiences to his subjects. The streets are clean, orderly, well-lit, and (unlike the Paris of his day) houses are numbered. Religious differences are calmly discussed and never result in violence. Strangely, from a present-day perspective, however, there is no new technology to speak of, and the political and social order remains intact: a king, nobility, clergy, and commoners occupy their respective places in society— they simply interact more “rationally.”

The Painting of Paris depicted an idealized version of Mercier’s contemporary society. With the exception of Britain’s constitutional monarchy and strong parliament, the monarchs of the major states of Europe succeeded in the eighteenth century in controlling governments that were at least “absolutist” in their pretensions, even though the nobility and local assemblies had a great deal of real power almost everywhere. In turn, the social orders were starkly divided, not just by wealth but by law and custom as well. This set of divisions was summarized in the system of “Estates” in France, the societal descendants of the divisions between “those who pray, those who fight, and those who work” in the Middle Ages.

The First Estate, consisting of the clergy, ran not just the churches, but education, enormous tracts of land held by the church and the monasteries, orders like the Jesuits and Benedictines, and great influence in royal government. In Protestant lands, there was the equivalent in the form of the official Lutheran or Anglican churches, although the political power of the clergy in Protestant countries was generally weaker than was the Roman Church in Catholic countries.

The Second Estate, the nobility, was itself divided by the elite titled nobility with hereditary lordships of various kinds (Dukes, Counts, etc.) and a larger group of lesser nobles who owned land but were not necessarily very wealthy. In Britain, the latter were called the gentry and controlled the House of Commons in parliament; the House of Lords was occupied by the “peers of the realm,” the elite families of nobles often descended from the ancient Normans. Generally, the nobility as a whole represented no more than 4% of the overall population (with peculiar exceptions such as Poland and Hungary that had large numbers of nobles, most of whom were scarcely wealthier than peasants).

The Third Estate was simply everyone else, from rich bankers and merchants without titles down to the destitute urban poor and landless peasant laborers. During the Middle Ages, the Third Estate was represented by wealthy elites from the cities and large towns, with the peasantry—despite being the majority of the population—enjoying no representation whatsoever. By the eighteenth century, the Third Estate was far more diverse, dynamic, and educated than ever before. It did not, however, enjoy better political representation. As the century went on, a growing number of members of the Third Estate, especially those influenced by Enlightenment thought, came to chafe at a political order that remained resolutely medieval in its basic structure.

Social Orders and Divisions

The Nobility

In most countries, the nobility maintained an almost complete monopoly of political power. The higher ranks of the clergy were drawn from noble families, so the church did not represent any kind of check or balance of power. The king, while now generally standing head-and-shoulders above the aristocracy individually, was still fundamentally the first among equals, “merely” the richest and most powerful person of the richest and most powerful family: the royal dynasty of the kingdom.

Despite the social and political changes of the preceding centuries, European nobles continued to enjoy tremendous legal and social privileges. Nobles owned a disproportionate amount of land, and in some kingdoms (like Russia), only nobles could own land. Only nobles could serve as officers in the army, reaping the spoils of war and generous salaries in the process. Only nobles had political representation in various parliamentary bodies, with the notable caveat that cities still held privileges of their own (the parlement of Paris, for example, wielded a great deal of meaningful power in French politics). Nobles had their own courts, were tried by their peers, and would subject to more humane treatment than were commoners. Perhaps most importantly, nobles everywhere paid few taxes, especially in comparison to the taxes, fees, and rents that beleaguered the peasantry.

A whole system of status symbols was maintained by both law and custom as well. To cite just a few, only members of the aristocracy could wear masks at masquerade balls, nobles led processions in towns and had special places to sit at operas and churches alike, and only nobles could wear swords during peacetime. Some of these legal separations were not trivial; only nobles could hunt game, and the legal systems of Europe viciously persecuted poachers even if the poachers were motivated by famine. Non-nobles were constantly reminded of their inferior status thanks to both the legal privileges enjoyed by nobles and the array of visible status symbols.

By the eighteenth century, the nobility actively cultivated learning and social grace, hearkening back to the glory days of the Renaissance courtier and bypassing the relatively uncouth period of the religious wars. Education, music, and art became fashionable in Europe in the eighteenth century, and being witty, well-dressed, musically talented, and well read became a status symbol almost as important as owning a lavish estate. The eighteenth century was the height of so-called “polite society” among the nobility: a legally reinforced elite that fancied themselves possessed of true “good taste.”

The Common People

The nobility also exercised considerable power over the (mostly rural) common people: peasants in the west and serfs in the east. Landowning lords had the right to extract financial dues, fees, and rents on peasants in the west. In the east, they had almost total control over the lives and movements of their serfs, including the requirement for serfs to perform lengthy periods of unpaid labor on behalf of their lords. In its most extreme manifestations, serfdom was essentially the same thing as slavery. Russian estates were even sold according to the number of serfs (“souls”) they contained rather than the physical size of the plot.

Starting in the late seventeenth century and culminating in the eighteenth, many kingdoms saw the gradual elimination of the common lands that had been an essential economic safety net for the peasantry in the earlier centuries. The nobility proved astute at reorganizing agriculture along more capitalistic lines, and in turn their land-hunger prompted laws of “enclosure,” especially in Britain. The result was ongoing, sometimes debilitating, pressure on the peasants. Many peasant families who had once owned small plots of their own had to sell them to rich nobles and became landless agricultural laborers, only one step up from the truly destitute who fled to the cities in search of either work or church charity.

Peasants often fought back, especially when the nobility tried to impose new fees or tried to cut them off from the commons. There were cases of rural revolts, of peasants hiring lawyers and taking their lords to royal courts, and other forms of resistance. There were also truly enormous uprisings in the east – in both the Austrian Empire and Russia, giant peasant uprisings succeeded in killing thousands of nobles, only to be eventually put down by brutal government suppression. Thus, the nobility were in increasing conflict with the peasantry, largely because the former were trying to extract more wealth from the latter.

Another new factor was the rise of the bourgeoisie, the non-noble urban mercantile class. The bourgeoisie became a very important class in terms of the economies of the kingdoms of Europe, especially in the west, yet it did not “fit” into the society of orders. While wealthy members of the bourgeoisie blended in with and sometimes married into the nobility, others thought of themselves as being distinct, celebrating a life of productive work and serious education over what they saw as the foppery and excess of the aristocracy. It was this latter self-conscious bourgeoisie that would play an important role in the revolutions of the end of the century. The (literate and urban) bourgeois class were also among those most keenly interested in Enlightenment ideas.

The Great Powers

The eighteenth century saw the emergence of five states, all of which were monarchies, comprising what would eventually be referred to as the Great Powers. Each of these states had certain characteristics: a strong ruling dynasty, a large and powerful army, and relative political stability. Over the course of the century, they jockeyed for position and power not only in Europe itself, but overseas: whole wars were fought between the Great Powers thousands of miles from Europe itself.

Of the Great Powers, France was regarded as the greatest at the time. France had the largest population, the biggest armies, the richest economy, and the greatest international prestige. Despite the fact that the crown was hugely debt-ridden, following Louis XIV’s wars and the fact that the next two kings were little better at managing money than he had been, the French monarchy was admired across Europe for its sophistication and power. French was also the international language by the eighteenth century: when a Russian nobleman encountered an Austrian and an Englishman, all three would speak French with one another.

In fact, the nobles of Europe largely thought of themselves in terms of a common aristocratic culture that had its heartland in France – Russian nobles often spoke Russian very poorly, and nobles of the German lands often regarded the German language as appropriate for talking to horses or commoners, but not to other nobles (supposedly, Frederick the Great of Prussia claimed that he used German to speak to his horse and other languages to speak to people). The French dynasty of the Bourbons, the descendants of Henry IV, continued the practice of keeping court at Versailles and only going into Paris when they had to browbeat the Parisian city government into ratifying royal laws.

Great Britain was both the perennial adversary of France in war during the eighteenth century and the most marked contrast in politics. As a constitutional monarchy, Britain was a major exception to the continental pattern of absolutism. While still exercising considerable power, the German-born royal line of the Hanovers deferred to parliament on matters of law-making and taxation after the Glorious Revolution of 1688. A written constitution reigned in anything smacking of “tyranny” and wistful continental philosophers like Voltaire often looked to Britain as the model of a more rational, fair-minded political system against which to contrast the abuses they perceived in their own political environments.

In addition to warring with France, the focus of the British government was on the expansion of the commercial overseas empire. France and Britain fought repeatedly in the eighteenth century over their colonial possessions. Britain enjoyed great success over the course of the century in pushing France aside as a rival in regions as varied as North America and India. On the verge of the French revolutionary and Napoleonic wars in the last decades of the century, Britain was poised to become the global powerhouse.

France’s traditional rival was the Habsburg line of Austria. What had once been the larger and more disparate empire of the Habsburgs was split into two different Habsburg empires in 1558, when the Holy Roman Emperor Charles V abdicated. Charles V handed his Spanish possessions to his son and his Holy Roman imperial possessions to his younger brother. The Spanish line died off in 1700 when the last Spanish Habsburg, Charles II, died without an heir, which prompted the War of the Spanish Succession as the Bourbons of France fought to put a French prince on the Spanish throne and practically every other major power in Europe rallied against them.

The Holy Roman line of Habsburgs remained strongly identified with Austria and its capital of Vienna. That line continued to rule the Austrian Empire, a political unit that united Austria, Hungary, Bohemia and various other territories in the southern part of Central Europe. While its nominal control of the Holy Roman Empire was all but political window dressing by the eighteenth century, the Austrian empire itself was by far the most significant German state and the Habsburgs of Austria were often the greatest threat to French ambitions on the continent.

The other German state of note was Prussia, the “upstart” great power. As noted in the discussion of absolutism, the Prussian royal line, the Hohenzollerns, oversaw the transformation of Prussia from a poor and backwards set of lands in northern Germany into a major military power, essentially by putting all state spending into the pursuit of military perfection. By the middle of the eighteenth century, the Prussian army was a match of the much larger Austrian force, with the two states emerging as military rivals.

Russia

While this textbook has traced the development of the other Great Powers, it has not considered the case of Russia to this point. That is simply because there was no unified state called “Russia” before the late fifteenth century. Originally populated by Slavic tribal groups, Swedish Vikings called the Rus colonized and then mixed with the native Slavs over the course of the ninth century. The Rus were led by princes who ruled towns that eventually developed into small cities, the most important of which was Kiev in the present-day country of Ukraine. The Rus were eventually converted to Eastern Orthodox Christianity thanks to the influence of Byzantium and its missionaries, but their historical development was undermined by the Mongol invasion of the thirteenth century. The period of Mongol rule is still referred to as the “Mongol yoke” in Russian history, meaning a period in which the Russian people were used as beasts of burden and sources of wealth by their Mongol lords, like animals yoked to plows.

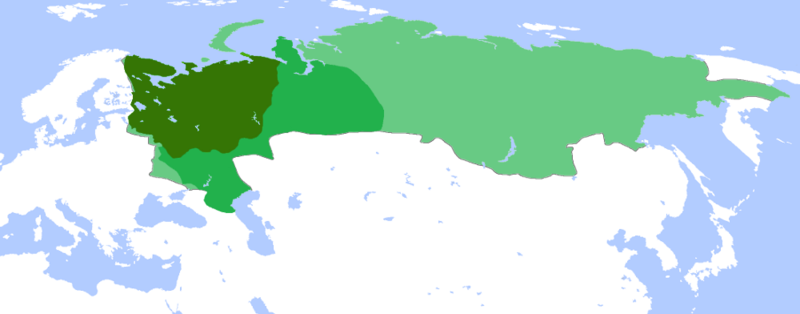

Russia emerged from the “Mongol yoke” thanks to the efforts of the Grand Prince of the city of Moscow, Ivan III (r. 1462 – 1505) and his grandson Ivan IV – “the Terrible” (r. 1533 – 1584). Ivan III was the prince of Muscovy, the territory around the city of Moscow, but thanks to his ruthless militarism, he expanded Muscovy’s influence to the Baltic Sea, fighting the Polish – Lithuanian Commonwealth to the west and conquering the prosperous city of Novgorod and its territories. He also overthrew the authority of the Mongol Golden Horde in his lands and began the process of permanently ending Mongol control in Russia. For the first time, a Russian prince had carved out a significant territory through conquest.

Two generations later, Ivan IV came to power in Muscovy. Ivan IV was, like his grandfather, a highly successful leader in war. Muscovy conquered a large part of the Mongol Golden Horde’s territory and also pushed back Turkic khans in the south. He dispatched explorers and hunters into Siberia, beginning the long process of the conquest of Siberia by Russia. He was also the first Russian ruler to claim the title of Tsar (also anglicized as Czar), meaning “Caesar.” Because Russia had adopted the Eastern Orthodox branch of Christianity centuries earlier, and because Constantinople (and the last remnant of the actual Roman Empire) fell to the Turks in 1453, Russian rulers after Ivan claimed that they were the true inheritors of the political power of the ancient Roman emperors. Just as the Holy Roman Emperors in the west claimed to be the political descendants of Roman authority (the German word “Kaiser,” too, means “Caesar”) so too did the Tsars of Russia.

Ivan IV was called The Terrible because of his incredible sadism: he had the beggars of Novgorod burned to death, he had nobles that displeased him ripped apart by wolves and dogs, and he crushed his own son’s skull with a club while in a rage. He had whole noble families slaughtered when he thought they posed a threat to his authority or were simply slow to respond to his demands that they serve him personally at his court. His overall goal was the transformation of the Russian nobles – called boyars – into servants of the state, one in which their power was based only on their loyalty to the Tsar. During his reign, he succeeded in asserting his authority through sheer brutality and terror.

After Ivan’s death in 1584, Russia was plunged into a 30-year period of anarchy called the Time of Troubles in which no one reigned as the recognized sovereign. Nobles reasserted their independence and Russia existed in a state of civil war (or armed anarchy, depending on one’s perspective) for decades. The period between rulers ended when an assembly of nobles elected the first member of the Romanov family to hold the title of Tsar in 1613, Michael I—but the Tsars remained weak and plagued by both resistance by nobles and huge peasant uprisings for many decades. One enormous peasant uprising, led by a man who claimed to be the “true” Tsar, threatened to overwhelm the forces of the real Tsar before being defeated in 1670.

The institution of serfdom was cemented in the midst of the chaos of the seventeenth century. When times were hard for Russian peasants, they frequent fled to the frontier, either Siberia or what would later be called the Ukraine (meaning “border region”). Since Russia was so enormous, this exacerbated an ongoing labor shortage problem. Unlike in the west, there was more than enough land in Russia, just not enough peasants to work it. Thus, the tsarist state instituted serfdom in 1649 across the board, formalizing what was already a widespread institution. This made peasants legally little better than slaves, forced to work the land and to serve the state in war when conscripted.

Russia’s transformation and engagement with the rest of Europe began in earnest under Tsar Peter I (the Great), r. 1682 – 1725. Up to that point, so little was known about Russia in the west that Louis XIV once sent a letter to a tsar who had been dead for twelve years. Russian nobles themselves tended to be uneducated and uncouth compared to their western counterparts, and the Russian Orthodox Church had little emphasis on the learning that now played such a major role in both the Catholic and Protestant churches of the west. Peter learned about Western Europe from visiting foreigners in his early twenties and decided to go and see what the west had to offer himself – he disguised himself as a normal workman (albeit one who was seven feet tall) and undertook a personal journey of discovery.

In the process, Peter personally learned about shipbuilding and military organization, returning intent on transforming the Russian state and military. He forced the Russian nobility to dress and act more like Western Europeans, sent Russian noble children abroad for their education, built an enormous navy and army to fight the Swedes and the Turks, and (on the backs of semi-slave labor) created the new port city of St. Petersburg as the new imperial capital. His military reforms were huge in scope – he instituted conscription in 1705 that required one out of every twenty serfs to serve for life in his armies, and he oversaw the construction of Russia’s navy from nothing. Over two-thirds of state revenues went to the military even after he instituted new taxes and royal monopolies. He also forced the boyars to undergo military education and serve as army officers, with all male nobles after 1722 required to serve the state either as civil officials or military officers.

Peter fought an ultimately unsuccessful war against the Ottomans in 1711, but he did capture some Turkish territory in the process; likewise, he seized the Baltic territories of Livonia and Estonia from what was then the unified kingdom of Poland – Lithuania (a state that began a rapid, painful decline over the course of the century). His major enemy, though, was Sweden. Sweden was a powerful late-medieval and early-modern kingdom. By the 1650s, Sweden ruled Denmark, Norway, Finland, and the Baltic region. The king Charles XI (r. 1660–1697) successfully imitated Louis XIV’s absolutism by pitting lesser nobles against greater ones, forcing the nobles to serve him directly. His son Charles XII (r. 1697–1718) was so arrogant that he snatched the crown from the hand of the Lutheran minister at his own coronation and put it on his head; he also refused to swear the normal coronation oath. He was the true paragon of Swedish absolutism.

Charles XII faced by an attempt by Denmark, joined by the German princedom of Saxony, to reassert its sovereignty in 1700. This turned into the Great Northern War (1700–1721) when Peter the Great joined in, intent on seizing Baltic territory for a permanent port. The Swedes defeated a large Russian army in 1700, but then Charles shifted his focus to Poland and Saxony rather than invading Russia itself. The Russians rallied and, in 1703, captured the mouth of the Neva River; Tsar Peter ordered the construction of his new capital city, St. Petersburg, the same year. The war dragged on for years, with Charles XII dying fighting a rebellion in Norway in 1718, leaving no heir. The Swedish forces were finally and definitively beaten in 1721, leaving Russia dominant in the Baltic region.

By the time Peter died (after contracting pneumonia or the flu from diving into the freezing Neva to save a drowning man) in 1725, the Russian Empire was now six times larger than it had been under Ivan the Terrible. Thanks to its territorial gains on the Baltic and the construction of St. Petersburg, it was now a resolutely European power, albeit an unusual one. While Russia suffered from a period of weak rule after Peter’s death, it was simply so large and the Tsar’s authority so absolute that it remained a great power.

In 1762, the Prussian-born empress Catherine (who later acquired the honorific “the Great”) seized power from her husband in a coup. Catherine would go on to introduce reforms meant to improve the Russian economy, creating the first state-financed banks and welcoming German settlers to the region of the Volga River to modernize farming practices. She also modernized the army and the state bureaucracy to improve efficiency. Despite being an enthusiastic supporter of “Enlightened” philosophy (as noted in the last chapter), Catherine was as focused on Russian expansion as Peter had been half a century earlier, seizing the Crimean Peninsula from the Ottoman Empire, expanding Russian power in Central Asia, and extinguishing Polish independence completely, with Poland divided between Russia, Prussia, and Austria in 1795. By her death in 1796 Russia was more powerful than ever before.

Wars

Raw economics became a major focus of war in the seventeenth century, when the rival commercial empires of Europe fought over territory and trade routes, not just glory and dynastic lines. The Dutch and British fought repeatedly from 1652 – 1675, conflicts which resulted in the loss of Dutch territory in North America (hence the city of New York instead of New Amsterdam). The British also fought the Spanish over various territories. The noteworthy result was that the formerly Spanish territory of Florida was handed over to the British in return for the Cuban port of Havana.

The most significant conflicts, however, were the ongoing series of wars between the two greatest powers of the eighteenth century: Britain and France. Britain had established naval dominance by 1700, but the French state was richer, its army much larger, and its navy almost Britain’s match. The French monarchy was also the established model of absolutism. Despite the financial savvy of the British government, most Europeans looked to France for their idea of a truly glorious state.

France became a highly aggressive power under Louis XIV, who saw territorial gains as essential to his own glory (he had the phrase “The Last Argument of Kings” stamped onto his cannons). His “grand strategy” was to seize territory from Habsburg Spain and Habsburg Austria by initiating a series of wars; he planned to force conquered populations to help pay for the wars and ultimately hoped to expand France to the Pyrenees in the south and the Rhine in the east. His wars in the late seventeenth century resulted in the seizure of small territories around the existing French borders, most notably in the Pyrenees. These wars, however, also drove the other powers of Europe into a defensive alliance against France, since it was clear that France threatened all of their interests (at one point Louis even tried to invade England; this would-be invasion was so unsuccessful it exists as a footnote in military history rather than the major event of something like the Spanish Armada).

The most significant war started by Louis was the War of the Spanish Succession (1701 – 1713). The last Spanish Habsburg died in 1700, and the heir was Louis’ grandson Philip. The Austrian Habsburgs rejected the legitimacy of the claim, and soon they recruited the British to help defeat France. The fighting dragged on for a decade as more European powers were drawn in. Finally, with France teetering on the edge of bankruptcy and Louis himself now old and ill, the powers agreed to negotiate. The results of the war were that Britain acquired additional territory in the Americas and a member of the Bourbon line was confirmed as the new Spanish king. However, the French and Spanish branches of the Bourbons were to be permanently distinct from one another: France would not control Spain, in other words. In addition, the Austrian Habsburgs absorbed the remaining Spanish possessions in Italy and the Habsburg-controlled parts of the Netherlands, meaning Spain was now bereft of its last European territories outside of the Iberian peninsula itself.

Conflicts continued on and off between the Great Powers even after the War of the Spanish Succession. The next major conflict was the Seven Years War (1756 – 1763), better known in America as the French and Indian War. The war began when Prussia attempted a blatant land grab from Austria, which quickly led to the involvement of the other Great Powers. This was a particularly bloody conflict, especially for the Native American tribes that allied with French or British colonial forces. The results of this war, another British victory, were far-reaching: France lost its Canadian possessions, including the entire French-speaking province of Quebec, it lost almost all of its territories in India, and Britain achieved dominance of commercial shipping to the Americas. While France was still the most powerful kingdom on the European continent, there were now no serious rivals to Britain on the oceans, something that allowed it to become the predominant imperial power in the world in the nineteenth century.

In turn, the Seven Years War directly led to the American Revolution (1775 – 1783). The British Parliament tried to impose unpopular taxes on the American colonists to help pay for the British troops garrisoned there during and after the Seven Years War. Open revolt broke out in 1775 and the Declaration of Independence was signed in 1776. The French provided both material and, then, actual military aid to the Americans starting in 1778, and Britain was finally forced to concede American independence in 1783. Significantly, this was the only war that France “won” over the course of the eighteenth century, and it gained nothing from it but the satisfaction of having finally beaten its British enemy. The real winners were the American colonists who were now able to go about creating an independent nation.

Conclusion

The eighteenth century was the culmination of many of the patterns that first came about in the late medieval and early Renaissance periods. The Great Powers were centralized, organized states with large armies and global economic ties. The social and legal divisions between different classes and categories were never more starkly drawn and enforced than they were by the eighteenth century. Wars explicitly fought in the name of gaining power and territory, often territory that spanned multiple continents (as in Britain’s seizure of French territory in both the Americas and India).

Ironically, given the apparent power and stability of this political and social order, everything was about to change. As the ideas of the Enlightenment spread and as the groups that made up the Third Estate of commoners grew increasingly resentful of their subservient political position, a virtual powder keg was being lit under the political structure of Europe. The subsequent explosion began in France in 1789.

Image Citations (Wikimedia Commons):

Three Social Orders – Public Domain

Holy Roman Empire – Robert Alfers

Expansion of Russia – Dbachmann

Peter the Great – Public Domain