Chapter 15: Culture, Science, and Pseudo-Science

Victorian Culture

Along with the enormous economic and political changes that occurred in Europe over the course of the nineteenth century came equally momentous shifts in culture and learning. The cultural era of this period is known as “Victorianism,” the culture of the dominant bourgeoisie in the second half of the nineteenth century. That culture was named after the British Queen Victoria, who presided over the zenith of British power and the height of British imperialism. Victoria’s astonishingly long reign, from 1837 to 1901, coincided with the triumph of bourgeois norms of behavior among self-understood elites.

Victorianism was the culture of top hats, of dresses that covered every inch of the female body, of rigid gender norms, and of an almost pathological fear of sexuality. Its defining characteristic was the desire for security, especially security from the influence of the lower classes. Class divisions were made visible in the clothing and manners of individuals, with each class outfitted in distinct “uniforms” – this was a time when one’s hat indicated one’s income and class membership. It was a time in which the bourgeoisie, increasingly mixed with the old nobility, came to assert a self-confident vision of a single European culture that, they thought, should dominate the world. Social elites insisted that scientific progress, economic growth, and their own increasing political power were all results of the superiority of European civilization, a civilization that had reached its pinnacle thanks to their own ingenuity. Particularly by the latter decades of the century, they characterized that superiority in racial terms.

According to the great Victorian psychologist Sigmund Freud, Victorianism was fundamentally about the repression of natural instincts. There were always threats present in the lives of social elites at the time: the threat of sexual impropriety, the threat of financial failure, the threat of immoral behavior being discovered in public, threats which were all tied to shame. There was clearly a Christian precedent for Victorian obsessions, and Victorianism was certainly tied to Christian piety. What had changed, however, is that the impulse to tie morality to a code of shame was secularized in the Victorian era to apply to everything, especially in economics. Simply put, there was a moral connection between virtue and economic success. The wealthy came to regard their social and economic status as proof of their strong ethical character, not just luck, connections, or hard work. Thus, Victorian culture included a belief in the existence of good and evil in the moral character of individuals, traits that science, they thought, should be able to identify just as it was now able to identify bacteria.

In turn, the Victorian bourgeoisie accused the working class of inherent weakness and turpitude. In the minds of the bourgeoisie, as the labor movements and socialist parties grew, the demands of the working class for shortened working days spoke not to their exhaustion and exploitation, but to their laziness and lack of work ethic. The Victorian bourgeoisie were the champions of the notion that everyone got what they deserved and that science itself would eventually ratify the social order. What the Victorian elite feared more than anything was that the working class would somehow overwhelm them, through a communist revolution or by simply “breeding” out of control. They tended to fear a concomitant national decline, sometimes even imagining that Western Civilization itself had reached its pinnacle and was doomed to degenerate.

There were some remarkable contrasts between the ideology of Victorian life and its lived reality. Even though much of the fear of social degeneration was exaggerated, it is also true that alcoholism became much more common (both because alcohol was cheaper and because urbanization lent itself to casual drinking), and drug use spread. Cocaine was regarded as a medicinal pick-me-up, and respectable diners sometimes finished meals with strawberries dipped in ether. Many novels written around the turn of the twentieth century critiqued the hypocrisy of social elites and their pretensions to rectitude. Two classics of horror writing, Dracula and Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde, are both about the monsters that lurked within bourgeois society. Both were written about Victorian elites who were actually terrible beasts, just under the surface of their respectable exteriors.

Nowhere was the Victorian obsession with defining and restricting people into carefully defined categories stronger than in gender roles. Male writers, theorists, and even scientists claimed that men and women were opposites: rational, forceful, naturally courageous men were contrasted with irrational, but gentle and demure, women. Men of all social classes dressed increasingly alike, in sensible, comfortable trousers, jackets, and hats (albeit with different hats for different classes). Women wore wildly impractical dresses with sometimes ludicrously tight corsets underneath, the better to serve their social function as ornaments to beautify the household. The stifling restrictions on women and their infantilization by men were major factors behind the rise of the feminist movement in the second half of the century, described below.

Scientific and Pseudo-Scientific Discoveries and Theories

Science made incredible advances in the Victorian era. Some of the most important breakthroughs had to do with medicine and biology. Those genuine advances, however, were accompanied by the growth of scholarship that claimed to be truly scientific, but that violated the tenets of the scientific method, employed sloppy methods, were based on false premises, or were otherwise simply factually inaccurate. Those fields constitute branches of “pseudo-”, meaning “false,” science.

Disease had always been the greatest threat to humankind before the nineteenth century—of the “four horsemen of the apocalypse,” it was Pestilence that traditionally delivered the most bodies to Death. In turn, the link between filth and disease had always been understood, but the rapid urbanization of the nineteenth century lent new urgency to the problem. This led to important advances in municipal planning, like modern sewer systems – London’s was built in 1848 after a terrible epidemic of cholera. Thus, before the mechanisms of contagion were understood, at least some means to combat it were nevertheless implemented in some European cities. Likewise, the first practical applications of chemistry to medicine occurred with the invention of anesthesia in the 1840s, allowing the possibility of surgery without horrendous agony for the first time in history.

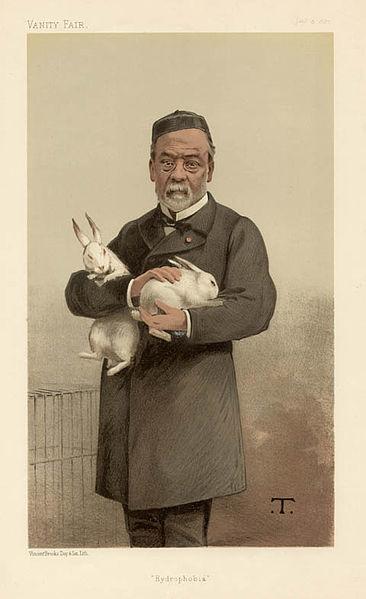

By far the most important advance in medicine, however, was in bacteriology, first pioneered by the French chemist Louis Pasteur (1822–1895). Starting with practical experiments on the process of fermentation in 1854, Pasteur built on his ideas and proved that disease was caused by microscopic organisms. Pasteur’s subsequent accomplishments are Newtonian in their scope: he definitively proved that the “spontaneous generation” of life was impossible and that microbes were responsible for putrefaction. He developed the aptly named technique of pasteurization to make foodstuffs safe (originally in service to the French wine industry), and he went on to develop effective vaccines against diseases like anthrax that affected both humans and animals. In the course of just a few decades, Pasteur overturned the entire understanding of health itself. Other scientists followed his lead, and by the end of the century, deaths in Europe by infectious disease dropped by a full sixty percent, primarily through improvements in hygiene (antibiotics would not be developed until the end of the 1920s).

These advances were met with understandable excitement. At the same time, however, they fed into a newfound obsession with cleanliness. All of a sudden, people understood that they lived in a dirty world full of invisible enemies: germs. Good hygiene became both a matter of survival and a badge of class identity for the bourgeoisie, and the inherent dirtiness of manual labor was further cause for bourgeois contempt for the working classes. For those who could afford the servants to do the work, homes and businesses were regularly scrubbed with caustic soaps, but there was little to be done in the squalor of working-class tenements and urban slums.

Comparable scientific breakthroughs occurred in the fields of natural history and biology. For centuries, naturalists (the term for what would later be known as biologists) had been puzzled by the fact that the fossils of marine animals could be found on mountaintops. Likewise, fossils embedded in rock were a conundrum that the biblical story of creation could not explain. By the early nineteenth century, some scientists argued that these phenomena could only occur through stratification of rock, a process that would take millions, not thousands, of years. The most famous geologist at the time was the British naturalist Charles Lyell, whose Principles of Geology went through eleven editions it was so popular among the reading public. Archeological discoveries in the middle of the century linked human civilization to very long time frames as well, with the discovery of ancient tools and the remains of settlements pushing the existence of human civilization back thousands of years from earlier concepts (all of which had been based on a literal interpretation of the Christian Bible).

In 1859, the English naturalist Charles Darwin published his Origin of the Species. In it, Darwin argued that lifeforms “evolve” over time thanks to random changes in their physical and mental structure. Some of these traits are beneficial and increase the likelihood that the individuals with them will survive and propagate, while others are not and tend to disappear as their carriers die off. Darwin based his arguments on both the fossil record and what he had discovered as the naturalist aboard a British research vessel, the HMS Beagle, that toured the coasts of South America and visited the Galapagos Islands off its west coast. There, Darwin had encountered numerous species that were uniquely adapted to live only in specific, limited areas. On returning to Britain, he concluded that only changes over time within species themselves could account for his discoveries.

Darwin’s arguments shocked most of his contemporaries. His theory directly contradicted the biblical account of the natural world, in which God’s creation is fundamentally static. In addition, Darwin’s account argued that nature itself was a profoundly hostile place to all living things; even as nature sustains species, it constantly tests individuals and kills off the weak. Evolutionary adaptations are random, not systematic, and are as likely to result in dangerous (for individuals) weaknesses as newfound sources of strength. There was no plan embedded in evolution, only random adaptation.

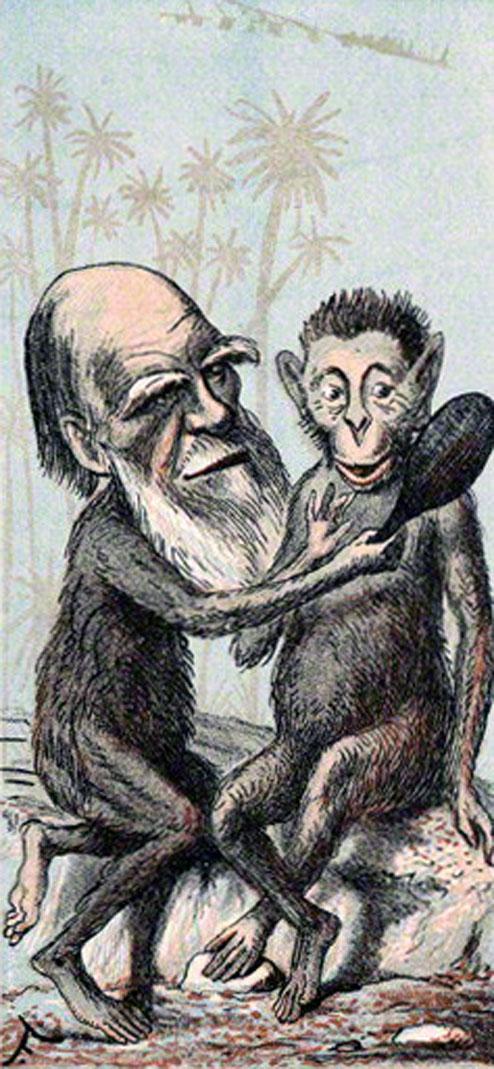

Nevertheless, Darwin’s theory was the first to systematically explain the existence of fossils and biological adaptation based on hard evidence. As early as 1870 three-quarters of British scientists believed evolutionary theory to be accurate, even before the mechanism by which evolution occurred, genetics, was understood. In 1871, in his Descent of Man, Darwin explicitly tied human evolution to his earlier model and argued that humans are descended from other hominids—the great apes. Despite popular backlash prompted by both religious conviction and the simple distaste of being related to apes, Darwinian theory went on to become one of the founding discoveries of modern biological science.

The mechanism of how evolution occurred, was not known during Darwin’s lifetime, at least to very many people. Unknown to anyone at the time, during the 1850s and 1860s an Austrian monk named Gregor Mendel carried out a series of experiments with pea plants in his monastery’s garden and, in the process, discovered the basic principles of genetics. Mendel first presented his work in 1865, but it was entirely forgotten. It was rediscovered by a number of scholars simultaneously in 1900, and in the process, was linked to Darwin’s evolutionary concepts. With the rediscovery of Mendel’s work, the mechanisms by which evolution occurs were revealed: it is in gene mutation that new traits emerge, and genes that favor the survival of offspring tend to dominate those that harm it.

Social Science and Pseudo-Science

Many Europeans regarded Darwinian theory as proof of progress: nature itself ensured that the human species would improve over time. Very quickly, however, evolutionary theory was taken over as a justification for both rigid class distinctions and racism. A large number of people, starting with elite male theorists, came to believe that Darwinism implied that a parallel kind of evolutionary process was at work in human society. In this view, success and power is the result of superior breeding, not just luck and education. The rich fundamentally deserve to be rich, and the poor (encumbered by their poor biological traits) deserve to be poor. This set of concepts came to be known as Social Darwinism. Drawing on the work of Arthur de Gobineau, the great nineteenth-century proponent of racial hierarchy described in a previous chapter, the British writer and engineer Herbert Spencer emerged as the most significant proponent of Social Darwinism. He summarized his outlook with the phrase “the survival of the fittest,” a phrase often misattributed to Darwin himself. Spencer was a fierce proponent of free market economics and also contributed to the process of defining human races in biological terms, rather than cultural or historical ones.

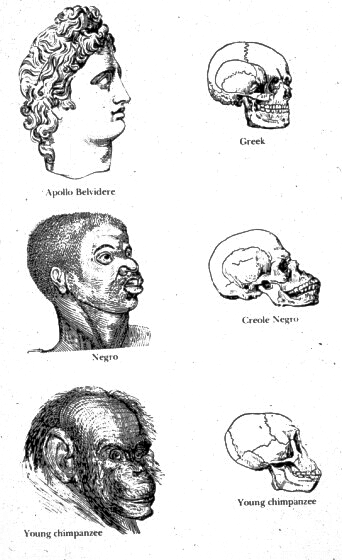

In turn, the new movement led an explosion of pseudo-scientific apologetics for notions of racial hierarchy. Usually, Social Darwinists claimed that it was not just that non-white races were inherently inferior, it was that they had reached a certain stage of evolution but stopped, while the white race had continued to evolve. Illustrations of the evolutionary process in late-nineteenth and early-twentieth century encyclopedias and dictionaries were replete with an evolutionary chain from small creatures through monkeys and apes and then on to non-white human races, culminating with the supposedly “fully evolved” European “race.”

In addition to non-white races, Social Darwinists targeted elements of their own societies for vilification, often lumping together various identities and behaviors as “unfit.” For Social Darwinists, the “unfit” included alcoholics, those who were promiscuous, unwed mothers, criminals, the developmentally disabled, and those with congenital disabilities. Social Darwinism’s prevailing theory was that charity or “artificial” checks on the exploitation of workers like trade unions would lead to the survival of the unfit, which would in turn cause the human species to decline. Likewise, charity, aid, and rehabilitation were misplaced, since they would supposedly lead to the survival of the unfit and thereby drag down the health of society overall. Thus, the best policy was to allow the “unfit” to die off if possible, and to try to impose limits on their breeding if not. Social Darwinism soon led to the field of eugenics, which advocated programs to sterilize the “unfit.”

Ironically, even as Social Darwinism provided a pseudo-scientific foundation for racist and sexist cultural assumptions, these notions of race and culture also fed into the fear of degeneration mentioned above. In the midst of the squalor of working-class life, or in terms of the increasing rates of drug use and alcoholism, many people came to fear that certain destructive traits were not only flourishing in Europe, but were being passed on. There was thus a great fear that the masses of the weak and unintelligent could and would spread their weakness through high birth rates, while the smart and capable were simply overwhelmed.

Not all of the theories to explain behavior were so morally and scientifically questionable, however. In the late nineteenth century, a Frenchman (Emile Durkheim) and a German (Max Weber) independently began the academic discipline that would become sociology: the systematic study of how people behave in complex societies. Durkheim treated Christianity like just another set of rituals and beliefs whose real purpose was the regulation of behavior, while Weber provided an enormous number of insights about the operation of governments, religious traditions, and educational institutions. Another German, Leopold von Ranke, created the first truly systematic forms of historical research, in turn creating the academic discipline of history itself.

Sociology and academic history were part of a larger innovation in human learning: the social sciences. These were disciplines that tried to deduce facts about human behavior that were equally valid to natural science’s various insights about the operations of the natural world. The dream of the social sciences was to arrive at rules of behavior, politics, and historical development that were as certain and unshakable as biology or geology. Unfortunately, as academic disciplines proliferated and scholars proposed theories to explain politics, social organization, and economics it was often difficult to distinguish between sound theories based on empirical evidence and pseudo-scientific or pseudo-scholarly theories (like those surrounding racial hierarchy) based instead on ideology and sloppy methodology.

Mass Culture

The Victorian era saw the emergence of the first modern, industrialized, “mass” societies. One of the characteristics of industrial societies, above and beyond industrial technology and the use of fossil fuels themselves, is the fact that culture itself becomes mass produced. Written material went from the form of books, which had been expensive and treated with great care in the early centuries of printing, to mass-market periodicals, newspapers, and cheap print. People went from inhabitants of villages and regions that were fiercely proud of their identities to inhabitants of larger and larger, and hence more anonymous and alienating, cities. Material goods, mass-produced, became much cheaper over the course of the nineteenth century thanks to industrialization, and in the process they could be used up and thrown away with a much more casual attitude by more and more people. Two examples of this phenomenon were the spread of literacy and the rise of consumerism.

The nineteenth century was the century of mass literacy. In France, male literacy was just below 50% as of the French Revolution, but it was almost 80% in 1870 and almost 100% just thirty years later. Female literacy was close behind. This had everything to do with the spread of printing in vernacular languages, as well as mass education. In France, mass secular free education happened in 1882 under the prime minister of the Third Republic, Jules Ferry. Free, public primary school did more to bind together the French in a shared national culture than anything before or since, as every child in France was taught in standard French and studied the same subjects.

Paper became vastly cheaper as well. Paper had long been made from rags, which were shredded, compressed together, and reconstituted. The resulting paper was durable but expensive. In the late nineteenth century printers began to make paper out of wood pulp, which dropped it to about a quarter of the former price. As of 1880, the linotype machine was invented, which also made printing much cheaper and more simple than it had been. Thus, it became vastly cheaper and easier to publish newspapers by the late nineteenth century.

There was also a positive change in the buying power of the average person. From 1850 to 1900, the average French person saw their real purchasing power increase by 165%. Comparable increases occurred in the other dynamic, commercial, and industrial economies of western Europe (and, eventually, the United States). This increase in the ability of average people to afford commodities above and beyond those they needed to survive was ultimately based on the energy unleashed by the Industrial Revolution. Even with the struggles over the quality of life of working people, by the late nineteenth century goods were simply so cheap to produce that the average person actually did enjoy a better quality of life and could buy things like consumables and periodicals.

One result of the cheapening of print and the rise in buying power was yellow journalism, sensationalized accounts of political events that stretched the truth to sell copies. In France, the first major paper of this type was called Le Petit Journal, an extremely inexpensive and sensationalistic paper which avoided political commentary in favor of banal, mainstream expressions of popular opinion. Rival papers soon sprang up, but what they had in common was that they did not try to change or influence opinion so much as they reinforced it—each political persuasion was now served by at least one newspaper that “preached to the choir,” reinforcing pre-existing ideological outlooks rather than confronting them with inconvenient facts.

Overall, the kind of journalism that exploded in the late nineteenth century lent itself to the cultivation of scandals. Important events and trends were tied to the sensationalizing journalism of the day. For instance, a naval arms race between Britain and Germany that was one of the causes of World War I had much to do with the press of both countries playing up the threat of being outpaced by their national rival. The Dreyfus Affair, in which a French Jewish army officer was falsely accused of treason, spun to the point that some people were predicting civil war thanks largely to the massive amount of press on both sides of the scandal (the Dreyfus Affair is considered in detail below). Likewise, imperialism, the practice of invading other parts of the world to establish and expand global empires, received much of its popular support from articles praising the civilizing mission involved in occupying a couple of thousand square miles in Africa that the reader had never heard of before.

In short, the politics of the latter part of the nineteenth century were embedded in journalism. As almost all of the states of Europe moved toward male suffrage, leaders were often shocked by the fact that they had to cultivate public opinion in order to pass the laws they supported. Journals became the mouthpieces of political positions, which both broadened the public sphere to an unprecedented extent and, in a way, sometimes cheapened political opinions to the level of banal slogans.

Another seismic shift occurred in the sphere of acquisition. In the early modern era, luxury goods were basically reserved for the nobility and the upper bourgeoisie. There simply was not enough social wealth for the vast majority of Europeans to buy many things they did not need. The average peasant or shopkeeper, even fairly prosperous ones, owned only a few sets of clothes, which were repaired rather than replaced over time. More to the point, most people did not think of money as something to “save” – in good years in which the average person somehow had “extra” money, he or she would simply spend it on more food or, especially for men, alcohol, because it was impossible to anticipate having a surplus again in the future.

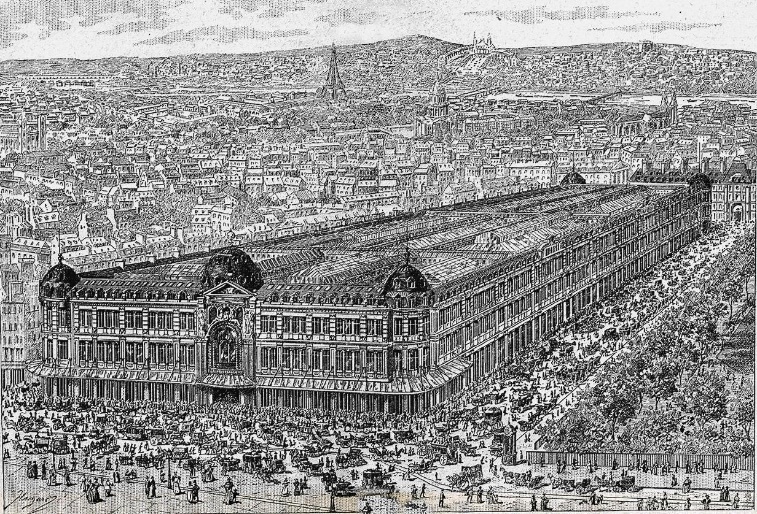

Perhaps the iconic example of a shift in patterns of acquisition and consumerism was the advent of department stores. Department stores represented the shift into recognizably modern patterns of buying, in which people shopped not just for necessities, but for small luxuries. The former patterns of consumption had been of small, family-run shops and traveling peddlers, a system in which bargaining was common and there was next to no advertising to speak of. With department stores, prices were fixed and a wide variety of goods of different genres were on display together. Advertising became ubiquitous, and branded products could be found across the length and breadth of a given country. Just as print and primary education inculcated national identity, so did the fact that consumer goods were increasingly standardized.

The first area to be affected by these shifts was textiles, both in terms of clothing and housewares like sheets and curtains. Manufacturing and semi-skilled labor dramatically decreased the price of textiles, and department stores carried large selections that many people could afford. People below the level of the rich came not only to own many different items of clothing, but they voluntarily replaced clothing due to shifts in fashion, not just because it was worn out.

The first real department store was the Bon Marché in Paris. It was built in the 1840s but underwent a series of expansions until it occupied an entire city block. By 1906 it had 4,500 employees. During the 1880s it had 10,000 clients a day, up to 70,000 a day during its February “white sales” in which it sold linens for reduced prices. The 1860s were the birth of the seaside holiday, which the Bon Marché helped invent by selling a whole range of holiday goods. By the 1870s there were mail-order catalogs and tourists considered a visit to the Bon Marché to be on the same level as one to the Arc de Triomphe built by Napoleon to commemorate his victories.

Ultimately, the Victorian Era saw the birth of modern consumerism, in which economies became dependent on the consumption of non-essential goods by ordinary people. The “mass society” inaugurated by the industrial revolution came of age in the last decades of the nineteenth century, a century after it had begun in the coal mines and textile mills of Northern England. That society, with its bourgeois standards, its triumphant self-confidence, and its deep-seated “scientific” social and racial attitudes, was in the process of taking over much of the world at precisely the same time.

Culture Struggles

As demonstrated by the conservative appropriation of nationalism in the cases of Italy and Germany, the stakes of political and cultural identity had changed significantly over the course of the nineteenth century. Within the nations of Europe—and for the first time in history it was appropriate to speak of nations instead of just “states”—major struggles erupted centering on national identity. After all, liberal and nationalistic legal frameworks had triumphed almost everywhere in Europe by turn of the twentieth century, but in significant ways the enfranchisement of each nation’s citizens was still limited. Most obviously, nowhere did women have the right to vote, and women’s legal rights in general were severely curtailed everywhere. Likewise, while voting rights existed for some male citizens in most nations by 1900 (generally, universal manhood suffrage came about only in the aftermath of World War I), conflicts remained concerning citizenship itself.

These struggles over national identity and legal rights occurred across Europe. The term “culture struggle” itself comes from Germany. Following German unification, Otto von Bismarck led an officially declared culture struggle – a Kulturkampf – against Roman Catholicism, and later, against socialism. The term lends itself, however, to a number of conflicts that occurred in Europe (and America) around the turn of the century, most significantly those having to do with feminism and with the legal and cultural status of European Jews.

The Kulturkampf was in part a product of Germany’s unique form of government. The political structure of the newly united nation of Germany set it apart from the far more liberal regimes in Britain and France. While there was an elected parliament, the Reichstag, it did not exercise the same degree of political power as did the British parliament or the French Chamber of Deputies and Senate. The German chancellor and the cabinet answered not to the Reichstag but to the Kaiser (the emperor), and while the regional governments had considerable control locally, the federal structure was highly authoritarian. In turn, there was a comparatively weak liberal movement in Germany because most German liberals saw the unification of Germany as a triumph and held Bismarck in high regard, despite his arch-conservative character. Likewise, most liberals detested socialism, especially as the German socialist party, the SPD, emerged in the 1870s as one of the most powerful political parties.

Bismarck represented the old Lutheran Prussian nobility, the Junkers, and he not only loathed socialism but also Catholicism. He (along with many other northern Germans) regarded Catholicism as alien to German culture and an existential threat to German unity. Since the Reformation of the sixteenth century, the majority of northern Germans had been Lutherans, and many were very hostile to the Catholic church. Still, 35% of Germans were Catholic, mostly in the south, and the Catholic Center Party emerged in 1870 to represent their interests. The same year the Catholic church issued the doctrine of papal infallibility—the claim that the Pope literally could not be wrong in manners of faith and doctrine—and Bismarck feared that a future pope might someday order German Catholics not to obey the state.

Thus, in 1873 he began an official state campaign against Catholics. Priests in Germany had to endure indoctrination from the state in order to be openly ordained, and the state would henceforth only recognize civil marriages. More laws followed, including the right of the state to expel priests who refused to abide by anti-Catholic measures. A young German Catholic tried to assassinate Bismarck in 1874, which only made him more intent on carrying forward with his campaign.

Soon, however, Bismarck realized that the state might need the alliance of the Catholic Center Party against the socialists, as the SPD continued to grow. Thus, he relaxed the anti-Catholic measures (although Catholics were still kept out of important state offices, as were Jews) and instead focused on measures against the SPD. Two assassination attempts against the Kaiser, despite being carried out by men who had nothing to do with socialism, gave Bismarck the pretext, and the Reichstag immediately passed laws that amounted to a ban on the SPD itself.

The SPD itself represented a major shift in the identity of socialism following the Revolutions of 1848. Whereas early socialists rarely organized into formal political parties—not least because most states in Europe before 1848 were not democracies of any kind—socialists in the post-1848 era became increasingly militant and organized. In September of 1864, a congress of socialists from across Europe and the United States gathered in London and founded the International Workingmen’s Association (the “First International”) in order to better coordinate their efforts. Within the nations of Europe, socialist parties soon acquired mass followings among the industrial working class, with the SPD joined by sister parties in France, Britain (where it was known as the Labour Party), Italy, and elsewhere.

The SPD was founded in 1875 out of various other socialist unions and parties that united in a single socialist movement. Bismarck was utterly opposed to socialism, and after mostly abandoning the anti-Catholic focus of the Kulturkampf, he pushed laws through the Reichstag in 1878 that banned the SPD and trade unions entirely. Ironically, however, individual socialists could still run for office and campaign for socialism. Bismarck’s response was typically pragmatic: he supported social legislation, including pensions for workers, in a bid to keep the socialists from attracting new members and growing even more militant. Thus, in an ironic historical paradox, some of the first “welfare state” provisions in the world were passed by a conservative government to weaken socialism.

The SPD was legalized again in 1890 (following the new Kaiser’s firing of Bismarck himself) and it issued a new manifesto for its goals. Like many of the other European socialist parties at the time, its ideological stance was explicitly Marxist. The party’s leaders asserted that Marx had been right in all of his major analyses, that capitalism would inevitably collapse, and that the party’s primary goal was thus to prepare the working class to rise up and take over in the midst of the coming crisis. Its secondary goals, the “in the meantime” activities, were focused on securing universal manhood suffrage and trying to shore up the quality of life of workers. This amounted to an uncomfortable hybrid of a revolutionary waiting game and a very routine pursuit of legislative benefits for workers.

This tension culminated in a fierce debate between two of the leaders of the SPD in the late 1890s: Karl Kautsky and Eduard Bernstein. Kautsky, the party leader who had written most of its theoretical manifestos, continued to insist that the real function of the party was to reject parliamentary alliances and to agitate for revolution. Bernstein, however, claimed that history had already proven that what the party should be doing was to improve the lives of workers in the present, not wait for a revolution that may or may not ever happen in the future. Bernstein was still a socialist, but he wanted the SPD to build socialism gradually; he called his theory “revisionism.” Ironically, the SPD rejected Bernstein’s revisionism, but what the party actually did was indeed “revisionist”: fighting for legal protection of workers, wages, and conditions of labor.

Comparable cases of historical irony marked many of the other socialist parties (Britain’s Labour Party was a noteworthy exception in that it never adopted Marxism). On the one hand, there were increasingly democratic parliaments and mass parties, and at least in some cases the beginning of social welfare laws. On the other hand, rather than the state socialist doctrines of Louis Blanc, the revolutionary, “scientific” socialism of Marxism became the official ideology of the majority of these parties. This practical split between socialism as social welfare and socialism as the revolutionary rejection of capitalism was to have serious consequences for the next hundred years of world history.

First-Wave Feminism

Even as socialist parties were growing in size and strength, another political and cultural conflict raged: the emergence of feminism. A helpful definition of feminism from the historians Bonnie Anderson and Judith Zinsser’s A History of Their Own asserts that feminism consists of the claim that women are fully human, not secondary or inferior to men, that women have been oppressed throughout history, and that women must recognize their solidarity with other women in order to end that oppression and create a more just and equitable society. Those claims go back centuries; perhaps the first distinctly feminist thinker in Western society was the Renaissance courtier Christine de Pizan (noted in the previous volume of this textbook), and later feminists like Mary Wollstonecraft expicitly linked the feminist demand for equality to the revolutionary promise of the American and French Revolutions of the late eighteenth century. It was not until the late nineteenth century, however, that a robust feminist movement emerged to champion women’s rights.

In the context of the Victorian era, most Europeans believed in the doctrine of gender relations known as “separate spheres.” In separate spheres, it was argued that men and women each had useful and necessary roles to play in society, but those roles were distinct from one another. The classic model of this concept was that the man’s job was to represent the family unit in public and make decisions that affected the family, while the woman’s job was to maintain order in the home and raise the children, albeit under the “veto” power of her husband. The Code Napoleon, in Article 231, proclaimed that the husband owed his wife protection, and the wife owed her husband obedience. Until the late nineteenth century, most legal systems officially classified women with children and the criminally insane in having no legal identity.

As of 1850, women across Europe could not vote, could not initiate divorce (in those countries in which divorce was even possible), could not control custody of children, could not pursue higher education, could not open bank accounts in their own name, could not maintain ownership of inherited property after marriage, could not initiate lawsuits or serve as legal witnesses, and could not maintain control of their own wages if working and married. Everywhere, domestic violence against women (and children) was ubiquitous; it was taken for granted the the “man of the house” had the right to enforce his will with violence if he found it necessary, and the very concept of marital rape was nonexistent as well. In sum, despite the claim by male socialists that the working class were the “wretched of the earth,” there is no question that male workers enjoyed vastly more legal rights than did women of any social class at the time.

What had changed since the dawn of the nineteenth century, however, was the growth of liberalism. It was a short, logical step from making the claim that “all men are equal” to “all people are equal,” and indeed some women (like Wollstonecraft) had very vocally emphasized just that point in the early liberal movement in the era of the French Revolution. By the late nineteenth century, liberal legal codes were present in some form in most of Europe, and after World War I all men won the vote in Britain, France, and Germany (along with most of the smaller countries in Central and Western Europe). Thus, early feminists argued that their enfranchisement was simply the obvious, logical conclusion of the political evolution of their century.

Late-nineteenth and early-twentieth century feminism is referred to by historians as “first-wave” feminism (there have been three “waves” so far). Its defining characteristic was the battle against legally mandated discrimination against women in terms of property laws, control over children within the family, and the right to vote. Of all of the culture struggles and legal battles of the period, however, first-wave feminism faced the greatest opposition from those in power: men. Biologists routinely claimed that women were simply physiologically less intelligent than men. Women who, against the odds, had risen to positions of note were constantly attacked and belittled; one example is the inaugural address of a new female scientist at the University of Athens in the early 1900s, whose speech was interrupted by male students shouting “back to the kitchen!” Queen Victoria herself once said that the demand for equal rights for women was “a mad, wicked folly…forgetting every sense of womanly feelings and propriety.”

In response, first-wave feminists argued that women were only “inferior” because of their inferior education. If they were educated at the same level and to the same standards as men, they would be able to exercise their reason at the same level as well, and would hence deserve to be treated as full equals by the law. As early as the French Revolution, some women had demanded equal rights for women as a logical outgrowth of the new, more just society under construction in the Revolution. The most famous revolutionary feminist of French Revolution, Olympe de Gouges, was executed for daring to argue that things like “equality” and “liberty” obviously implied that men and women should be equals. A century later, her vision remained unfulfilled.

One of first-wave feminism’s major goals was women’s suffrage: the right of women to vote. In 1867 in Britain the National Society for Women’s Suffrage was founded. Comparable movements spread across the continent over the next three decades. The word “feminist” itself came about in 1890, after a French Suffrage activist, Hubertine Auclert, described herself as such (Auclert made a name for herself in part because she refused to pay taxes, arguing that since she was not represented politically, she had no obligation to contribute to the state). Only in Finland and Norway, however, did women gain the vote before World War I. In some cases, it took shockingly long for women to get the vote: France only granted it in 1944 as a concession to the allies who liberated the country from the Nazis, and it took Switzerland until 1971(!).

The struggle for the vote was closely aligned to other feminist campaigns. In fact, it would be misleading to claim that first-wave feminism was primarily focused on suffrage, since suffrage itself was seen by feminists as only one component of what was needed to realize women’s equality. An iconic example is the attitude of early feminists to marriage: for middle class women, marriage was a necessity, not a choice. Working class women worked in terrible conditions just to survive, while the truly desperate were often driven to prostitution not because of a lack of morality on their part but because of brutal economic and legal conditions for unmarried poor women. In turn, middle class women suffered the consequences when their husbands, succumbing to the temptation of prostitution, brought sexually transmitted diseases into the middle class home. Women, feminists argued, needed economic independence, the ability to support themselves before marriage without loss of status or respectability, and the right to retain the property and earnings they brought to and accumulated during marriage. Voting rights and the right to initiate divorce were thus “weapons of self defense” according to first wave feminists.

After decades of campaigns by feminists, divorce became a possibility in countries like Britain and France in the late nineteenth century, but it remained difficult and expensive to secure. For a woman to initiate divorce, she had to somehow have the means to hire a lawyer and navigate labyrinthine divorce laws; as a result, only the well-off could do so. In other countries, like Russia, divorce remained illegal. Much more common than legal separation was the practice of men simply abandoning their wives and families when they tired of them; this made the institutions of middle-class family life open to mockery by socialists, who, as did Marx and Engels, pointed out that marriage was nothing but a property contract that men could choose to abandon at will (the socialist attitude toward feminism, incidentally, was that gender divisions were byproducts of capitalism: once capitalism was eliminated, gender inequality would supposedly vanish as well).

Even as the feminist movement in Britain became focused on voting rights, feminists waged other battles as well. In the 1870s and 1880s, British feminists led by Josephine Butler attacked the Contagious Diseases Act, which subjected prostitutes to mandatory gynecological inspections (but did not require the male clients of prostitutes to be examined), and drew the radical conclusion that prostitution was simply the most obvious example of a condition that applied to practically all women. In marriage, after all, women exchanged sexual access to their bodies in return for their material existence. Butler’s campaign weathered years of failure and scorn before finally triumphing: the Contagious Diseases Act was repealed and the age of consent for girls was raised from twelve(!) to sixteen.

The demand for the vote, however, was stymied by the fact that male politicians across the political spectrum refused to champion the issue, albeit for different reasons. On the political right, the traditional view that women had no place in politics prevailed. On the left, however, both liberal and socialist politicians were largely in support of women’s suffrage…in theory. In practice, however, leftist politicians (falling prey to yet more sexist stereotypes) feared that women would vote for traditional conservatives because women “naturally” longed for the comfort and protection of tradition. Thus, even nominally sympathetic male politicians repeatedly betrayed promises to push the issue forward in law.

While most feminists persisted in peaceful demands for reform, others were galvanized by these political betrayals and turned to militancy. In Britain, the best known militant feminists were the Pankhursts: the mother Emmeline (1858 – 1928) and daughters Christabel and Sylvia, who formed a radical group known as the Suffragettes in 1903. Much of the original membership came from the ranks of Lancashire textile workers before the group moved its headquarters to London in 1906. The Pankhursts soon severed their links with the Labour Party and working class activists and began a campaign of direct action under the motto “deeds, not words”. By 1908 they had moved from heckling to stone-throwing and other forms of protest, including destroying paintings in museums and, on one occasion, attacking male politicians with horsewhips on a golf course. In the meantime, both militant and non-militant feminists did succeed in making women’s suffrage a mainstream political issue: as many as 500,000 women and pro-feminist men gathered at one London rally in 1908.

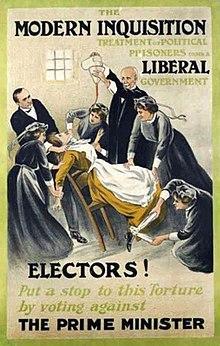

Militant activists who staged public demonstrations were on several occasions treated brutally by police, and those who were arrested were subjected to coercive feeding when they went on hunger strikes. That brutality led to more widespread public support for the Suffragettes, but there were still no legal changes forthcoming; even the British Liberal Party that had, on various occasions, claimed to support women’s suffrage always ended up putting it on the back burner in parliament. In the most spectacular and tragic act of protest, a Suffragette named Emily Davison threw herself under the horse owned by the British king George V during the Derby (the hugely popular national horse race) of 1913 and was killed. In the aftermath it was discovered that she had stuffed her dress with pamphlets demanding the vote for women.

Somewhat ironically, given the importance of the suffrage movement, feminists secured other legal rights before they did the right to vote in the period before World War I. By and large, women secured the right to enter universities by the early twentieth century and the first female academics secured teaching positions soon after. The first woman to hold a university post in France was the famous Marie Curie, whose work was instrumental in understanding radiation. Women secured the right to initiate divorce in some countries even earlier, along with the right to control their own wages and property and to fight for the custody of children. In short, thanks to feminist agitation, women had secured a legal identity and meaningful legal rights in at least some of the countries of Europe, and the United States, by the onset of World War I in 1914, but as mentioned above, only in two Scandinavian countries could they yet vote.

Modern Anti-Semitism

The great irony of feminism—or, rather, the need for feminism—was that women were not a “minority” but nevertheless faced prejudice, violence, and legal restrictions. European Jews, on the other hand, were a minority everywhere they lived. Furthermore, because of their long, difficult, and often violent history facing persecution from the Christian majority, Jews faced a particularly virulent and deep-seated form of hatred from their non-Jewish neighbors. That hatred, referred to as anti-Semitism (also spelled antisemitism), took on new characteristics in the modern era that, if anything, made it even more dangerous

Jews had been part of European society since the Roman Empire. In the Middle Ages, Jews were frequently persecuted, expelled, or even massacred by the Christian majority around them. Jews were accused of responsibility for the death of Christ, were blamed for plagues and famines, and were even thought to practice black magic. Jews were unable to own land, to marry Christians, or to practice trades besides sharecropping, peddling goods, and lending money (since Christians were banned from lending money at interest until the late Middle Ages, the stereotypes of Jewish greed originated with the fact that money-lending was one of the only trades Jews could perform). Starting with the late period of the Enlightenment, however, some Jews were grudgingly “emancipated” legally, being allowed to move to Christian cities, own land, and practice professions they had been banned from in the past.

That legal emancipation was complete almost everywhere in Europe by the end of the nineteenth century, although the most conservative states like Russia still maintained anti-Semitic restrictions. Anti-Jewish hatred, however, did not vanish. Instead, in the modern era, Jews were vilified for representing everything that was wrong with modernity itself. Jews were blamed for urbanization, for the death of traditional industries, for the evils of modern capitalism, but also for the threat of modern socialism, for being anti-union and for being pro-union, for both assimilating to the point that “regular” Germans and Frenchmen and Czechs could no longer tell who was Jewish, and for failing to assimilate to the point that they were “really” the same as everyone else. To modern anti-Semites, Jews were the scapegoat for all of the problems of the modern world itself.

At the same time, modern anti-Semitism was bound up with modern racial theories, including Darwinian evolutionary theory, its perverse offspring Social Darwinism, and the Eugenics movement which sought to purify the racial gene pool of Europe (and America). Many theorists came to believe that Jews were not just a group of people who traced their ancestry back to the ancient kingdom of Judah, but were in fact a “race,” a group defined first and foremost by their blood, their genes, and by supposedly inexorable and inherent characteristics and traits.

Between vilification for the ills of modernity and the newfound obsession with race that swept across European and American societies in the late nineteenth century, there was ample fuel for the rise of anti-Semitic politics. The term anti-Semitism itself was invented and popularized by German and Austrian politicians in the late nineteenth century—an Anti-Semitic League emerged in Germany in the 1870s under the leadership of a politician named Wilhelm Marr. Marr claimed that Jews had “without striking a blow” “become the socio-political dictator of Germany.” In fact, Jews were about 1% of the German population and, while well-represented in business and academia, they had negligible political influence. Following Marr’s efforts, other parties emerged over the course of the 1880s.

Parties whose major platform was anti-Semitism itself, however, faded from prominence in the 1890s. The largest single victory won by anti-Semitic political parties in the German Empire was in 1893, consisting of only 2.9% of the vote. Subsequently, however, mainstream right-wing parties adopted anti-Semitism as part of their platform. Thus, even though parties that defined themselves solely by anti-Semitism diminished, anti-republican, militaristic, and strongly Christian-identified parties on the political right in France, Austria, and Germany soon started using anti-Semitic language as part of their overall rhetoric.

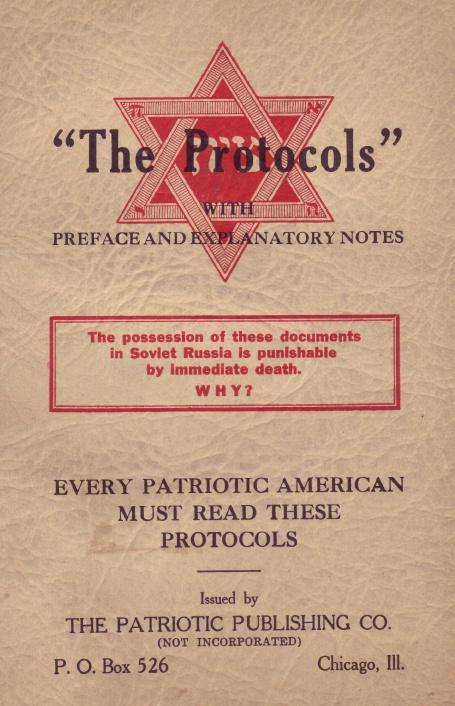

Along with the new, racist, version of anti-Semitism, the modern conspiracy theory of global Jewish influence was a distinctly modern phenomenon. A Prussian pulp novelist named Hermann Goedsche published a novel in 1868 that included a completely fictional meeting of a shadowy conspiracy of Rabbis who vowed to seize global power in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries through Jewish control of world banking. That “Rabbi’s Speech” was soon republished in various languages as if it had actually happened. Better known was the Protocols of the Elders of Zion, a document claiming to be the minutes from a meeting of international Jewish leaders that copied whole sections Goedsche’s “Speech” and combined them with various equally spurious accounts of Jewish political machinations. The Protocols were first published in 1903 by the Russian secret police as justification for continued anti-Semitic restrictions in the Russian Empire, and they subsequently became important after World War I when they were used as “proof” that the Jews had caused the war in order to disrupt the international political order.

Another iconic moment in the history of anti-Semitism occurred in France in the 1890s, when a French Jewish military officer named Alfred Dreyfus was framed for espionage, stripped of his rank, and imprisoned. An enormous public debate broke out in French society over Dreyfus’s guilt or innocence which revolved around his identity as a French Jew. “Anti-Dreyfusards” argued that no Jew could truly be a Frenchman and that Dreyfus, as a Jew, was inherently predisposed to lie and cheat, while “Dreyfusards” argued that anyone could be a true, legitimate French citizen, Jews included.

In the end, the “Dreyfus Affair” culminated in Dreyfus’s exoneration and release, but not before anti-Semitism was elevated to one of the defining characteristics of anti-liberal, authoritarian right-wing politics in France. Some educated European Jews concluded that the pursuit of not just legal equality, but cultural acceptance was doomed given the strength and virulence of anti-Semitism in European culture, and they started a new political movement to establish a Jewish homeland in the historical region of ancient Israel. That movement, Zionism, saw a slow but growing migration of European Jews settling in the Levant, at the time still part of the Ottoman Empire. Decades later, it culminated in the emergence of the modern state of Israel in 1948.

Conclusion

The growth of science, the pernicious development of pseudo-science, and the culture struggles that raged in European society all occurred simultaneously, lending to an overall sense of disruption and uncertainty as the twentieth century dawned. Lives were transformed for the better by consumerism and medical advances, but many Europeans still found the sheer velocity of change overwhelming and threatening. At least some of the virulence of the culture struggles of the era was due to this sense of fear and displacement, fears that spilled over to the growing rivalries between nations. In turn, the world itself provided the stage on which those rivalries played out as European nations set themselves the task of conquering and controlling vast new empires overseas.

Image Citations (Wikimedia Commons):

Queen Victoria – Public Domain

Pasteur – Public Domain

Darwin – Public Domain

Racial Hierarchy – Public Domain

Bon Marché – Creative Commons License

Force Feeding – Public Domain

Protocols of the Elders of Zion – Public Domain