“We tend to think that we have rational relationships to information, but we don’t. We have emotional relationships to information, which is why the most effective disinformation draws on our underlying fears and worldviews….We’re less likely to be critical of information that reinforces our worldview or taps into our deep-seated emotional responses” (Wardle, qtd. in Vongkiatkajorn; emphasis added).

Background

In an information environment shaped by algorithms, the attention economy, engagement, and polarization, how do we determine truth? How do we know which sources of information to trust? These questions are becoming increasingly difficult to answer, and even more so as “disinformation that is designed to provoke an emotional reaction can flourish in these spaces” (Wardle).

Indeed, in 2016, Oxford Dictionaries selected post-truth as the Word of the Year, defining this as: “relating to or denoting circumstances in which objective facts are less influential in shaping public opinion than appeals to emotion and personal belief.” To learn more about how this emotional appeal causes unconscious defensiveness when an opinion gets challenged (called the backfire effect), check out the Oatmeal’s You’re Not Going to Believe What I’m About to Tell You.

Trust

A 2020 study from Project Information Literacy confirms that the way information is delivered today—with opinion and propaganda mingled with traditional news sources, and with algorithms highlighting sources based on engagement rather than quality—has left many college students concerned about the trustworthiness of online content. Students reported that it was difficult to know where to place their trust when credible sources are buried by a deluge of poorer-quality content and misinformation. One student noted that “it’s not that we’re lacking credible information. It’s that we’re drowning in, like, a sea of all these different points out there” (Head, et al. 20).

“This is happening at a time when falsehoods proliferate and trust in truth-seeking institutions is being undermined. Even the very existence of truth itself has come into question….People no longer know what to believe or on what grounds we can determine what is true” (Head, et al. 11, 36).

Essential Definitions

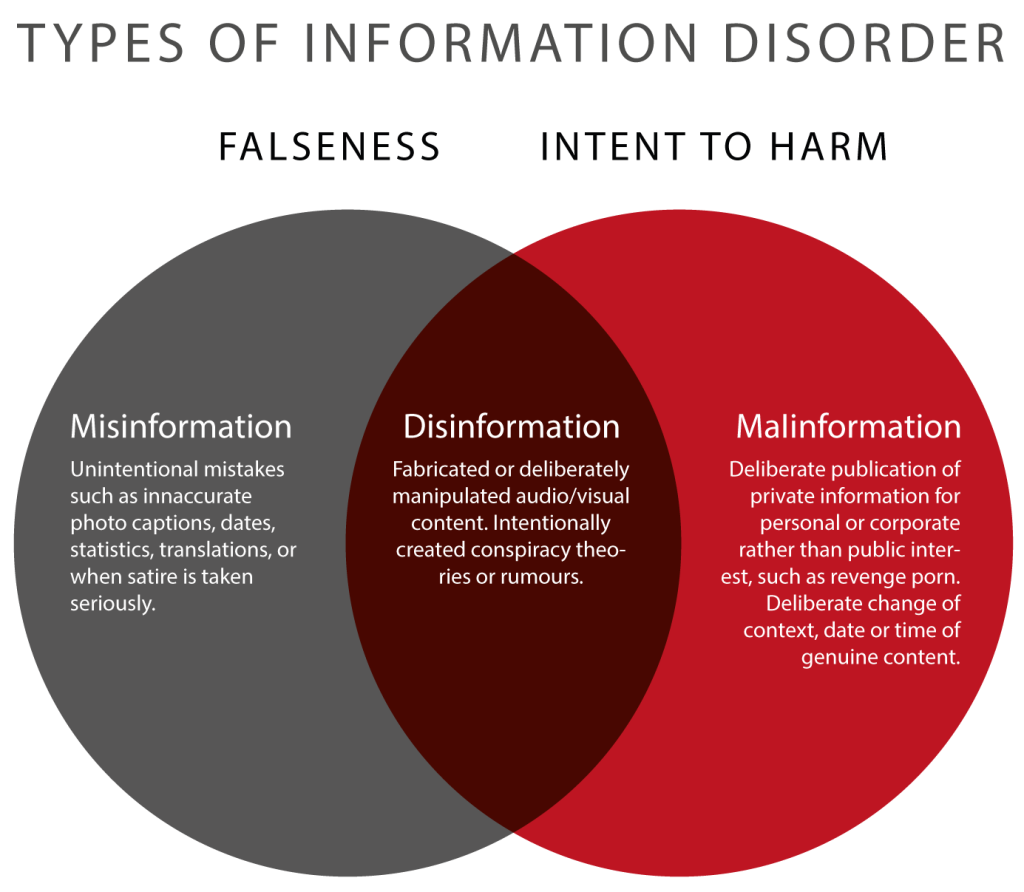

First, it is important to establish a shared vocabulary and terminology so that we can better understand and discuss these concepts. Claire Wardle, a world-renowned expert in the areas social media, user generated content, and verification, has used “information disorder” as an umbrella term for the various types of false, misleading, manipulated, or deceptive information we have seen flourish in recent years. She also created an essential glossary for information disorder, with definitions for related words and phrases. For example, you will find helpful definitions for terms like algorithm, bots, data mining, deepfakes, doxing, sock puppet, and trolling.

The graphic below illustrates the scale and range of intent behind false information, from unintentionally inaccurate to deliberately deceptive and harmful. For a much more detailed explanation of each form of information disorder, from “satire” to “fabricated content” to “false context,” see First Draft’s Essential Guide to Understanding Information Disorder.

Concept Review Exercise: Information Disorder

Sources

This section includes material from the source book, Introduction to College Research, as well as the following:

“First Draft’s Essential Guide to Understanding Information Disorder” by Claire Wardle is licensed under CC BY-NC-ND 4.0.

Head, Alison J., Barbara Fister, and Margy MacMillan. “Information Literacy in the Age of Algorithms.” Project Information Literacy, 15 Jan. 2020. Licensed under CC BY-NC-SA 4.0.

Image: “3 Types of Information Disorder” graphic by Claire Wardle & Hossein Derakshan is licensed under CC BY-NC-ND 3.0.

Image: “Cognition and Emotion” by ElisaRiva on Pixabay.

Image: “Line Mind” by ElisaRiva on Pixabay.

Inman, Matthew. “You’re Not Going to Believe What I’m About to Tell You.” The Oatmeal, 2020.

“Oxford Word of the Year 2016.” Oxford Languages, Oxford University Press.

Vongkiatkajorn, Kanyakrit. “Here’s How You Can Fight Back Against Disinformation.” Mother Jones, 9. Aug. 2018.

Wardle, Claire. “Information Disorder, Part 1: The Essential Glossary.” First Draft, 9 July 2018.

Original material by book author Calantha Tillotson.

Another strategy you can use to assure any information you use is credible is the Currency, Relevance Authority, Accuracy, and Purpose (CRAAP) Test. The CRAAP test is a list of questions that you can ask yourself to determine if the information you have found is reliable.

Currency – The timeliness of the information. Some questions to ask yourself to determine the currency of the information you have found are:

- When was the information created?

- Has the information been updated before?

- Based on your needs, is it out-of-date?

Relevance – The importance of the information based on your needs. Some questions to ask yourself to determine the relevancy of the information you have found are:

- Does the information relate back to your topic or answer your question?

- Is the information at the appropriate content level?

- Who is the intended audience?

Authority – The source of the information. Some questions to ask yourself about the source of the information you have found are:

- Are the author’s credentials or affiliations provided?

- Does the author's background qualify them to write on the topic of the information?

- What does the URL reveal?

Accuracy – The reliability of the information. Some questions to ask yourself to determine the accuracy of the information you have found are:

- Does the information contain any references?

- Can you verify any of the information provided?

- Are the sources that are cited scholarly?

Purpose – The reason the information exists. Some questions to ask yourself about the purpose of the information you have found are:

- Is the information a fact or opinion?

- What is the purpose of the information (persuade, inform, entertain, etc...)?

Source

Blakeslee, S. (2010). Evaluating information–Applying the CRAAP test. Retrieved from http://www.csuchico.edu/lins/handouts/eval_websites.pdf

Another strategy you can use to assure any information you use is credible is the Currency, Relevance Authority, Accuracy and Purpose (CRAAP) Test.

- Currency – The timeliness of the information. Some questions to ask yourself to determine the currency of the information you have found are:

- When was the information created?

- Has the information been updated before?

- Based on your needs, is it out-of-date?

- Relevance – The importance of the information based on your needs. Some questions to ask yourself to determine the relevancy of the information you have found are:

- Does the information relate back to your topic or answer your question?

- Is the information the appropriate content level?

- Who is the intended audience?

- Authority – The source of the information. Some questions to ask yourself about the source of the information you have found are:

- Are the author’s credentials or affiliations provided?

- Does the author's background qualify them to write on the topic of the information?

- What does the URL reveal?

- Accuracy – The reliability of the information. Some questions to ask yourself to determine the accuracy of the information you have found are:

- Does the information contain any references?

- Can you verify any of the information provided?

- Are the sources that are cited scholarly?

- Purpose – The reason the information exists. Some questions to ask yourself about the purpose of the information you have found are:

- Is the information a fact or opinion?

- What is the purpose of the information (persuade, inform, entertain, etc...)?

Learning Objectives

By the end of this chapter, you will be able to:

Learning Objectives

By the end of this chapter, you will be able to:

- Recognize bias and methods to avoid bias as a consumer and producer of information

Learning Objectives

By the end of this chapter, you will be able to:

- Identify the psychological, physiological, and sociological effects of disinformation

- Recognize bias and methods to avoid bias as a consumer and producer of information

- Describe information hygiene and info-environmentalism

Learning Objectives

By the end of this chapter, you will be able to:

- Identify the psychological, physiological, and sociological effects of disinformation

- Recognize bias and methods to avoid bias as a consumer and producer of information

- Describe information hygiene and info-environmentalism