45 Finding the Good Argument OR Why Bother With Logic?

Rebecca Jones

The word argument often means something negative. In Nina Paley’s cartoon (see Figure 1), the argument is literally a cat fight. Rather than envisioning argument as something productive and useful, we imagine intractable sides and use descriptors such as “bad,” “heated,” and “violent.” We rarely say, “Great, argument. Thanks!” Even when we write an academic “argument paper,” we imagine our own ideas battling others.

Linguists George Lakoff and Mark Johnson explain that the controlling metaphor we use for argument in western culture is war:

It is important to see that we don’t just talk about arguments in terms of war. We actually win or lose arguments. We see the person we are arguing with as an opponent. We attack his positions and we defend our own. We gain and lose ground. We plan and use strategies. If we find a position indefensible, we can abandon it and take a new line of attack. Many of the things we do in arguing are partially structured by the concept of war. (4)

If we follow the war metaphor along its path, we come across other notions such as, “all’s fair in love and war.” If all’s fair, then the rules, principles, or ethics of an argument are up for grabs. While many warrior metaphors are about honor, the “all’s fair” idea can lead us to arguments that result in propaganda, spin, and, dirty politics. The war metaphor offers many limiting assumptions: there are only two sides, someone must win decisively, and compromise means losing. The metaphor also creates a false opposition where argument (war) is action and its opposite is peace or inaction. Finding better arguments is not about finding peace—the opposite of antagonism. Quite frankly, getting mad can be productive. Ardent peace advocates, such as Jane Addams, Mahatma Gandhi, and Martin Luther King, Jr., offer some of the most compelling arguments of our time through concepts like civil disobedience that are hardly inactive. While “argument is war” may be the default mode for Americans, it is not the only way to argue. Lakoff and Johnson ask their readers to imagine something like “argument is dance” rather than “argument is war” (5). While we can imagine many alternatives to the war metaphor, concepts like argument as collaboration are more common even if they are not commonly used. Argument as collaboration would be more closely linked to words such as dialogue and deliberation, cornerstone concepts in the history of American democracy.

However, argument as collaboration is not the prevailing metaphor for public argumentation we see/hear in the mainstream media. One can hardly fault the average American for not being able to imagine argument beyond the war metaphor. Think back to the coverage of the last major election cycle. The opponents on either side (democrat/republican) dug in their heels and defended every position, even if it was unpopular or irrelevant to the conversation at hand. The political landscape divided into two sides with no alternatives. In addition to the entrenched positions, blogs and websites such as FactCheck.org flooded us with lists of inaccuracies, missteps, and plain old fallacies that riddled the debates. Unfortunately, the “debates” were more like speeches given to a camera than actual arguments deliberated before the public. These important moments that fail to offer good models lower the standards for public argumentation.

On an average news day, there are entire websites and blogs dedicated to noting ethical, factual, and legal problems with public arguments, especially on the news and radio talk shows. This is not to say that all public arguments set out to mislead their audiences, rather that the discussions they offer masquerading as arguments are often merely opinions or a spin on a particular topic and not carefully considered, quality arguments. What is often missing from these discussions is research, consideration of multiple vantage points, and, quite often, basic logic.

On news shows, we encounter a version of argument that seems more like a circus than a public discussion. Here’s the visual we get of an “argument” between multiple sides on the average news show. In this example (see Figure 2), we have a four ring circus.

While all of the major networks use this visual format, multiple speakers in multiple windows like The Brady Bunch for the news, it is rarely used to promote ethical deliberation. These talking heads offer a simulation of an argument. The different windows and figures pictured in them are meant to represent different views on a topic, often “liberal” and “conservative.” This is a good start because it sets up the possibility for thinking through serious issues in need of solutions. Unfortunately, the people in the windows never actually engage in an argument (see Thinking Outside the Text). As we will discuss below, one of the rules of good argument is that participants in an argument agree on the primary standpoint and that individuals are willing to concede if a point of view is proven wrong. If you watch one of these “arguments,” you will see a spectacle where prepared speeches are hurled across the long distances that separate the participants. Rarely do the talking heads respond to the actual ideas/arguments given by the person pictured in the box next to them on the screen unless it is to contradict one statement with another of their own. Even more troubling is the fact that participants do not even seem to agree about the point of disagreement. For example, one person might be arguing about the congressional vote on health care while another is discussing the problems with Medicaid. While these are related, they are different issues with different premises. This is not a good model for argumentation despite being the predominant model we encounter.

Activity: Thinking Outside the Text

Watch the famous video of Jon Stewart on the show Crossfire: (http:// www.youtube.com/watch?v=vmj6JADOZ-8).

- What is Stewart’s argument?

- How do the hosts of Crossfire respond to the very particular argument that Stewart makes?

- Why exactly are they missing the point?

These shallow public models can influence argumentation in the classroom. One of the ways we learn about argument is to think in terms of pro and con arguments. This replicates the liberal/conservative dynamic we often see in the papers or on television (as if there are only two sides to health care, the economy, war, the deficit). This either/or fallacy of public argument is debilitating. You are either for or against gun control, for or against abortion, for or against the environment, for or against everything. Put this way, the absurdity is more obvious. For example, we assume that someone who claims to be an “environmentalist” is pro every part of the green movement. However, it is quite possible to develop an environmentally sensitive argument that argues against a particular recycling program. While many pro and con arguments are valid, they can erase nuance, negate the local and particular, and shut down the very purpose of having an argument: the possibility that you might change your mind, learn something new, or solve a problem. This limited view of argument makes argumentation a shallow process. When all angles are not explored or fallacious or incorrect reasoning is used, we are left with ethically suspect public discussions that cannot possibly get at the roots of an issue or work toward solutions.

Activity: Finding Middle Ground

Outline the pro and con arguments for the following issues:

- Gun Control

- Cap and Trade

- Free Universal Healthcare

In a group, develop an argument that finds a compromise or middle ground between two positions.

Rather than an either/or proposition, argument is multiple and complex. An argument can be logical, rational, emotional, fruitful, useful, and even enjoyable. As a matter of fact, the idea that argument is necessary (and therefore not always about war or even about winning) is an important notion in a culture that values democracy and equity. In America, where nearly everyone you encounter has a different background and/or political or social view, skill in arguing seems to be paramount, whether you are inventing an argument or recognizing a good one when you see it.

The remainder of this chapter takes up this challenge—inventing and recognizing good arguments (and bad ones). From classical rhetoric, to Toulmin’s model, to contemporary pragma-dialectics, this chapter presents models of argumentation beyond pro and con. Paying more addition to the details of an argument can offer a strategy for developing sound, ethically aware arguments.

What Can We Learn from Models of Argumentation?

So far, I have listed some obstacles to good argument. I would like to discuss one other. Let’s call it the mystery factor. Many times I read an argument and it seems great on the surface, but I get a strange feeling that something is a bit off. Before studying argumentation, I did not have the vocabulary to name that strange feeling. Additionally, when an argument is solid, fair, and balanced, I could never quite put my finger on what distinguished it from other similar arguments. The models for argumentation below give us guidance in revealing the mystery factor and naming the qualities of a logical, ethical argument.

Classical Rhetoric

In James Murphy’s translation of Quintilian’s Institutio Oratoria, he explains that “Education for Quintilian begins in the cradle, and ends only when life itself ends” (xxi). The result of a life of learning, for Quintilian, is a perfect speech where “the student is given a statement of a problem and asked to prepare an appropriate speech giving his solution” (Murphy xxiii). In this version of the world, a good citizen is always a PUBLIC participant. This forces the good citizen to know the rigors of public argumentation: “Rhetoric, or the theory of effective communication, is for Quintilian merely the tool of the broadly educated citizen who is capable of analysis, reflection, and powerful action in public affairs” (Murphy xxvii). For Quintilian, learning to argue in public is a lifelong affair. He believed that the “perfect orator . . . cannot exist unless he is above all a good man” (6). Whether we agree with this or not, the hope for ethical behavior has been a part of public argumentation from the beginning.

The ancient model of rhetoric (or public argumentation) is complex. As a matter of fact, there is no single model of ancient argumentation. Plato claimed that the Sophists, such as Gorgias, were spin doctors weaving opinion and untruth for the delight of an audience and to the detriment of their moral fiber. For Plato, at least in the Phaedrus, public conversation was only useful if one applied it to the search for truth. In the last decade, the work of the Sophists has been redeemed. Rather than spin doctors, Sophists like Isocrates and even Gorgias, to some degree, are viewed as arbiters of democracy because they believed that many people, not just male, property holding, Athenian citizens, could learn to use rhetoric effectively in public.

Aristotle gives us a slightly more systematic approach. He is very concerned with logic. For this reason, much of what I discuss below comes from his work. Aristotle explains that most men participate in public argument in some fashion. It is important to note that by “men,” Aristotle means citizens of Athens: adult males with the right to vote, not including women, foreigners, or slaves. Essentially this is a homogenous group by race, gender, and religious affiliation. We have to keep this in mind when adapting these strategies to our current heterogeneous culture. Aristotle explains,

. . . for to a certain extent all men attempt to discuss statements and to maintain them, to defend themselves and to attack others. Ordinary people do this either at random or through practice and from acquired habit. Both ways being possible, the subject can plainly be handled systematically, for it is possible to inquire the reason why some speakers succeed through practice and others spontaneously; and every one will at once agree that such an inquiry is the function of an art. (Honeycutt, “Aristotle’s Rhetoric” 1354a I i)

For Aristotle, inquiry into this field was artistic in nature. It required both skill and practice (some needed more of one than the other). Important here is the notion that public argument can be systematically learned.

Aristotle did not dwell on the ethics of an argument in Rhetoric (he leaves this to other texts). He argued that “things that are true and things that are just have a natural tendency to prevail over their opposites” and finally that “ . . . things that are true and things that are better are, by their nature, practically always easier to prove and easier to believe in” (Honeycutt, “Aristotle’s Rhetoric” 1355a I i). As a culture, we are skeptical of this kind of position, though I think that we do often believe it on a personal level. Aristotle admits in the next line that there are people who will use their skills at rhetoric for harm. As his job in this section is to defend the use of rhetoric itself, he claims that everything good can be used for harm, so rhetoric is no different from other fields. If this is true, there is even more need to educate the citizenry so that they will not be fooled by unethical and untruthful arguments.

For many, logic simply means reasoning. To understand a person’s logic, we try to find the structure of their reasoning. Logic is not synonymous with fact or truth, though facts are part of evidence in logical argumentation. You can be logical without being truthful. This is why more logic is not the only answer to better public argument.

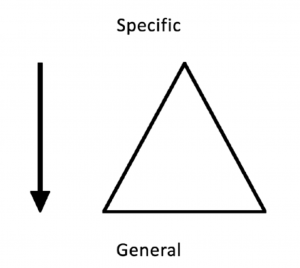

Our human brains are compelled to categorize the world as a survival mechanism. This survival mechanism allows for quicker thought. Two of the most basic logical strategies include inductive and deductive reasoning. Deductive reasoning (see Figure 3) starts from a premise that is a generalization about a large class of ideas, people, etc. and moves to a specific conclusion about a smaller category of ideas or things (All cats hate water; therefore, my neighbor’s cat will not jump in our pool). While the first premise is the most general, the second premise is a more particular observation. So the argument is created through common beliefs/observations that are compared to create an argument. For example:

People who burn flags are unpatriotic. Major Premise

Sara burned a flag. Minor Premise

Sara is unpatriotic. Conclusion

The above is called a syllogism. As we can see in the example, the major premise offers a general belief held by some groups and the minor premise is a particular observation. The conclusion is drawn by comparing the premises and developing a conclusion. If you work hard enough, you can often take a complex argument and boil it down to a syllogism. This can reveal a great deal about the argument that is not apparent in the longer more complex version.

Stanley Fish, professor and New York Times columnist, offers the following syllogism in his July 22, 2007, blog entry titled “Democracy and Education”: “The syllogism underlying these comments is (1) America is a democracy (2) Schools and universities are situated within that democracy (3) Therefore schools and universities should be ordered and administrated according to democratic principles.”

Fish offered the syllogism as a way to summarize the responses to his argument that students do not, in fact, have the right to free speech in a university classroom. The responses to Fish’s standpoint were vehemently opposed to his understanding of free speech rights and democracy. The responses are varied and complex. However, boiling them down to a single syllogism helps to summarize the primary rebuttal so that Fish could then offer his extended version of his standpoint (see link to argument in Question #1 at the end of the text).

Inductive reasoning moves in a different direction than deductive reasoning (see Figure 4). Inductive reasoning starts with a particular or local statement and moves to a more general conclusion. I think of inductive reasoning as a stacking of evidence. The more particular examples you give, the more it seems that your conclusion is correct.

Inductive reasoning is a common method for arguing, especially when the conclusion is an obvious probability. Inductive reasoning is the most common way that we move around in the world. If we experience something habitually, we reason that it will happen again. For example, if we walk down a city street and every person smiles, we might reason that this is a “nice town.” This seems logical. We have taken many similar, particular experiences (smiles) and used them to make a general conclusion (the people in the town are nice). Most of the time, this reasoning works. However, we know that it can also lead us in the wrong direction. Perhaps the people were smiling because we were wearing inappropriate clothing (country togs in a metropolitan city), or perhaps only the people living on that particular street are “nice” and the rest of the town is unfriendly. Research papers sometimes rely too heavily on this logical method. Writers assume that finding ten versions of the same argument somehow prove that the point is true.

Here is another example. In Ann Coulter’s book, Guilty: Liberal “Victims” and Their Assault on America, she makes her (in)famous argument that single motherhood is the cause of many of America’s ills. She creates this argument through a piling of evidence. She lists statistics by sociologists, she lists all the single moms who killed their children, she lists stories of single mothers who say outrageous things about their life, children, or marriage in general, and she ends with a list of celebrity single moms that most would agree are not good examples of motherhood. Through this list, she concludes, “Look at almost any societal problem and you will find it is really a problem of single mothers” (36). While she could argue, from this evidence, that being a single mother is difficult, the generalization that single motherhood is the root of social ills in America takes the inductive reasoning too far. Despite this example, we need inductive reasoning because it is the key to analytical thought (see Activity: Applying Inductive and Deductive Reasoning). To write an “analysis paper” is to use inductive reasoning.

Activity: Applying Deductive and Inductive Reasoning

For each standpoint, create a deductive argument AND an inductive argument. When you are finished, share with your group members and decide which logical strategy offers a more successful, believable, and/or ethical argument for the particular standpoint. Feel free to modify the standpoint to find many possible arguments.

- a. Affirmative Action should continue to be legal in the United States. b. Affirmative Action is no longer useful in the United States.

- The arts should remain an essential part of public education.

- Chose a very specific argument on your campus (parking, tuition, curriculum) and create deductive and inductive arguments to support the standpoint.

Most academic arguments in the humanities are inductive to some degree. When you study humanity, nothing is certain. When observing or making inductive arguments, it is important to get your evidence from many different areas, to judge it carefully, and acknowledge the flaws. Inductive arguments must be judged by the quality of the evidence since the conclusions are drawn directly from a body of compiled work.

The Appeals

“The appeals” offer a lesson in rhetoric that sticks with you long after the class has ended. Perhaps it is the rhythmic quality of the words (ethos, logos, pathos) or, simply, the usefulness of the concept. Aristotle imagined logos, ethos, and pathos as three kinds of artistic proof. Essentially, they highlight three ways to appeal to or persuade an audience: “(1) to reason logically, (2) to understand human character and goodness in its various forms, (3) to understand emotions” (Honeycutt, Rhetoric 1356a).

While Aristotle and others did not explicitly dismiss emotional and character appeals, they found the most value in logic. Contemporary rhetoricians and argumentation scholars, however, recognize the power of emotions to sway us. Even the most stoic individuals have some emotional threshold over which no logic can pass. For example, we can seldom be reasonable when faced with a crime against a loved one, a betrayal, or the face of an adorable baby.

The easiest way to differentiate the appeals is to imagine selling a product based on them. Until recently, car commercials offered a prolific source of logical, ethical, and emotional appeals.

Logos: Using logic as proof for an argument. For many students this takes the form of numerical evidence. But as we have discussed above, logical reasoning is a kind of argumentation.

Car Commercial: (Syllogism) Americans love adventure—Ford Escape allows for off road adventure— Americans should buy a Ford Escape.

OR

The Ford Escape offers the best financial deal.

Ethos: Calling on particular shared values (patriotism), respected figures of authority (MLK), or one’s own character as a method for appealing to an audience.

Car Commercial: Eco-conscious Americans drive a Ford Escape.

OR

[Insert favorite movie star] drives a Ford Escape.

Pathos: Using emotionally driven images or language to sway your audience.

Car Commercial: Images of a pregnant women being safely rushed to a hospital. Flash to two car seats in the back seat. Flash to family hopping out of their Ford Escape and witnessing the majesty of the Grand Canyon.

OR

After an image of a worried mother watching her sixteen year old daughter drive away: “Ford Escape takes the fear out of driving.”

The appeals are part of everyday conversation, even if we do not use the Greek terminology (see Activity: Developing Audience Awareness). Understanding the appeals helps us to make better rhetorical choices in designing our arguments. If you think about the appeals as a choice, their value is clear.

Activity: Developing Audience Awareness

Imagine you have been commissioned by your school food service provider to create a presentation encouraging the consumption of healthier foods on campus.

- How would you present this to your friends: consider the media you would use, how you present yourself, and how you would begin.

- How would you present this same material to parents of incoming students?

- Which appeal is most useful for each audience? Why?

Toulmin: Dissecting the Everyday Argument

Philosopher Stephen Toulmin studies the arguments we make in our everyday lives. He developed his method out of frustration with logicians (philosophers of argumentation) that studied argument in a vacuum or through mathematical formulations:

All A are B. All B are C.

Therefore, all A are C. (Eemeren, et al. 131)

Instead, Toulmin views argument as it appears in a conversation, in a letter, or some other context because real arguments are much more complex than the syllogisms that make up the bulk of Aristotle’s logical program. Toulmin offers the contemporary writer/reader a way to map an argument. The result is a visualization of the argument process. This map comes complete with vocabulary for describing the parts of an argument. The vocabulary allows us to see the contours of the landscape—the winding rivers and gaping caverns. One way to think about a “good” argument is that it is a discussion that hangs together, a landscape that is cohesive (we can’t have glaciers in our desert valley). Sometimes we miss the faults of an argument because it sounds good or appears to have clear connections between the statement and the evidence, when in truth the only thing holding the argument together is a lovely sentence or an artistic flourish.

For Toulmin, argumentation is an attempt to justify a statement or a set of statements. The better the demand is met, the higher the audience’s appreciation. Toulmin’s vocabulary for the study of argument offers labels for the parts of the argument to help us create our map.

Claim: The basic standpoint presented by a writer/ speaker.

Data: The evidence which supports the claim.

Warrant: The justification for connecting particular data to a particular claim. The warrant also makes clear the assumptions underlying the argument.

Backing: Additional information required if the warrant is not clearly supported.

Rebuttal: Conditions or standpoints that point out flaws in the claim or alternative positions.

Qualifiers: Terminology that limits a standpoint. Examples include applying the following terms to any part of an argument: sometimes, seems, occasionally, none, always, never, etc.

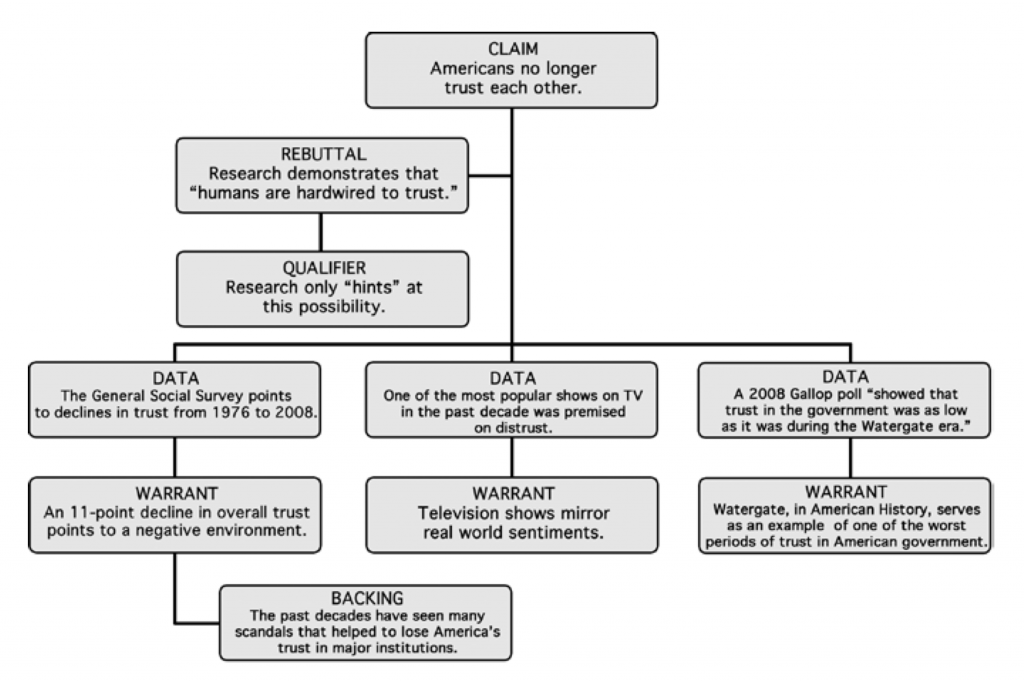

The following paragraphs come from an article reprinted in UTNE magazine by Pamela Paxton and Jeremy Adam Smith titled: “Not Everyone Is Out to Get You.” Charting this excerpt helps us to understand some of the underlying assumptions found in the article.

“Trust No One”

That was the slogan of The X-Files, the TV drama that followed two FBI agents on a quest to uncover a vast government conspiracy. A defining cultural phenomenon during its run from 1993–2002, the show captured a mood of growing distrust in America.

Since then, our trust in one another has declined even further. In fact, it seems that “Trust no one” could easily have been America’s motto for the past 40 years—thanks to, among other things, Vietnam, Watergate, junk bonds, Monica Lewinsky, Enron, sex scandals in the Catholic Church, and the Iraq war.

The General Social Survey, a periodic assessment of Americans’ moods and values, shows an 11-point decline from 1976–2008 in the number of Americans who believe other people can generally be trusted. Institutions haven’t fared any better. Over the same period, trust has declined in the press (from 29 to 9 percent), education (38–29 percent), banks (41 percent to 20 percent), corporations (23–16 percent), and organized religion (33–20 percent). Gallup’s 2008 governance survey showed that trust in the government was as low as it was during the Watergate era.

The news isn’t all doom and gloom, however. A growing body of research hints that humans are hardwired to trust, which is why institutions, through reform and high performance, can still stoke feelings of loyalty, just as disasters and mismanagement can inhibit it. The catch is that while humans want, even need, to trust, they won’t trust blindly and foolishly.

Figure 5 demonstrates one way to chart the argument that Paxton and Smith make in “Trust No One.” The remainder of the article offers additional claims and data, including the final claim that there is hope for overcoming our collective trust issues. The chart helps us to see that some of the warrants, in a longer research project, might require additional support. For example, the warrant that TV mirrors real life is an argument and not a fact that would require evidence.

Charting your own arguments and others helps you to visualize the meat of your discussion. All the flourishes are gone and the bones revealed. Even if you cannot fit an argument neatly into the boxes, the attempt forces you to ask important questions about your claim, your warrant, and possible rebuttals. By charting your argument you are forced to write your claim in a succinct manner and admit, for example, what you are using for evidence. Charted, you can see if your evidence is scanty, if it relies too much on one kind of evidence over another, and if it needs additional support. This charting might also reveal a disconnect between your claim and your warrant or cause you to reevaluate your claim altogether.

Pragma-Dialectics: A Fancy Word for a Close Look at Argumentation

The field of rhetoric has always been interdisciplinary and so it has no problem including argumentation theory. Developed in the Speech Communication Department at the University of Amsterdam, pragma-dialectics is a study of argumentation that focuses on the ethics of one’s logical choices in creating an argument. In Fundamentals of Argumentation Theory: A Handbook of Historical Backgrounds and Contemporary Developments, Frans H. van Eemeren and Rob Grootendorst describe argumentation, simply, as “characterized by the use of language for resolving a difference of opinion” (275). While much of this work quite literally looks at actual speech situations, the work can easily be applied to the classroom and to broader political situations.

While this version of argumentation deals with everything from ethics to arrangement, what this field adds to rhetorical studies is a new approach to argument fallacies. Fallacies are often the cause of the mystery feeling we get when we come across faulty logic or missteps in an argument.

What follows is an adaptation of Frans van Eemeren, Rob Grootendorst, and Francesca Snoeck Henkemans’ “violations of the rules for critical engagement” from their book Argumentation: Analysis, Evaluation, Presentation (109). Rather than discuss rhetorical fallacies in a list (ad hominem, straw man, equivocation, etc.), they argue that there should be rules for proper argument to ensure fairness, logic, and a solution to the problem being addressed. Violating these rules causes a fallacious argument and can result in a standoff rather than a solution.

While fallacious arguments, if purposeful, pose real ethical problems, most people do not realize they are committing fallacies when they create an argument. To purposely attack someone’s character rather than their argument (ad hominem) is not only unethical, but demonstrates lazy argumentation. However, confusing cause and effect might simply be a misstep that needs fixing. It is important to admit that many fallacies, though making an argument somewhat unsound, can be rhetorically savvy. While we know that appeals to pity (or going overboard on the emotional appeal) can often demonstrate a lack of knowledge or evidence, they often work. As such, these rules present argumentation as it would play out in a utopian world where everyone is calm and logical, where everyone cares about resolving the argument at hand, rather than winning the battle, and where everyone plays by the rules. Despite the utopian nature of the list, it offers valuable insight into argument flaws and offers hope for better methods of deliberation.

What follows is an adaptation of the approach to argumentation found in Chapters 7 and 8 of Argumentation: Analysis, Evaluation, Presentation (Eemeren, et al. 109-54). The rule is listed first, followed by an example of how the rule is often violated.

1. The Freedom Rule

“Parties must not prevent each other from putting forward standpoints or casting doubt on standpoints” (110).

There are many ways to stop an individual from giving her own argument. This can come in the form of a physical threat but most often takes the form of a misplaced critique. Instead of focusing on the argument, the focus is shifted to the character of the writer or speaker (ad hominem) or to making the argument (or author) seem absurd (straw man) rather than addressing its actual components. In the past decade, “Bush is stupid” became a common ad hominem attack that allowed policy to go unaddressed. To steer clear of the real issues of global warming, someone might claim “Only a fool would believe global warming is real” or “Trying to suck all of the CO2 out of the atmosphere with giant greenhouse gas machines is mere science fiction, so we should look at abandoning all this green house gas nonsense.”

2. The Burden-of-Proof Rule

“A party who puts forward a standpoint is obliged to defend it if asked to do so” (113).

This is one of my favorites. It is clear and simple. If you make an argument, you have to provide evidence to back it up. During the 2008 Presidential debates, Americans watched as all the candidates fumbled over the following question about healthcare: “How will this plan actually work?” If you are presenting a written argument, this requirement can be accommodated through quality, researched evidence applied to your standpoint.

3. The Standpoint Rule

“A party’s attack on a standpoint must relate to the standpoint that has indeed been advanced by the other party” (116).

Your standpoint is simply your claim, your basic argument in a nutshell. If you disagree with another person’s argument or they disagree with yours, the actual standpoint and not some related but more easily attacked issue must be addressed. For example, one person might argue that the rhetoric of global warming has created a multi-million dollar green industry benefiting from fears over climate change. This is an argument about the effects of global warming rhetoric, not global warming itself. It would break the standpoint rule to argue that the writer/speaker does not believe in global warming. This is not the issue at hand.

4. The Relevance Rule

“A party may defend his or her standpoint only by advancing argumentation related to that standpoint” (119).

Similar to #3, this rule assures that the evidence you use must actually relate to your standpoint. Let’s stick with same argument: global warming has created a green industry benefiting from fears over climate change. Under this rule, your evidence would need to offer examples of the rhetoric and the resulting businesses that have developed since the introduction of green industries. It would break the rules to simply offer attacks on businesses who sell “eco-friendly” products.

5. The Unexpressed Premise Rule

“A party may not falsely present something as a premise that has been left unexpressed by the other party or deny a premise that he or she has left implicit” (121).

This one sounds a bit complex, though it happens nearly every day. If you have been talking to another person and feel the need to say, “That’s NOT what I meant,” then you have experienced a violation of the unexpressed premise rule. Overall, the rule attempts to keep the argument on track and not let it stray into irrelevant territory. The first violation of the rule, to falsely present what has been left unexpressed, is to rephrase someone’s standpoint in a way that redirects the argument. One person might argue, “I love to go to the beach,” and another might respond by saying “So you don’t have any appreciation for mountain living.” The other aspect of this rule is to camouflage an unpopular idea and deny that it is part of your argument. For example, you might argue that “I have nothing against my neighbors. I just think that there should be a noise ordinance in this part of town to help cut down on crime.” This clearly shows that the writer does believe her neighbors to be criminals but won’t admit it.

6. The Starting Point Rule

“No party may falsely present a premise as an accepted starting point, or deny a premise representing an accepted starting point” (128).

Part of quality argumentation is to agree on the opening standpoint. According to this theory, argument is pointless without this kind of agreement. It is well known that arguing about abortion is nearly pointless as long as one side is arguing about the rights of the unborn and the other about the rights of women. These are two different starting points.

7. The Argument Scheme Rule

“A standpoint may not be regarded as conclusively defended if the defense does not take place by means of an appropriate argument scheme that is correctly applied” (130).

This rule is about argument strategy. Argument schemes could take up another paper altogether. Suffice it to say that schemes are ways of approaching an argument, your primary strategy. For example, you might choose emotional rather than logical appeals to present your position. This rule highlights the fact that some argument strategies are simply better than others. For example, if you choose to create an argument based largely on attacking the character of your opponent rather than the issues at hand, the argument is moot.

Argument by analogy is a popular and well worn argument strategy (or scheme). Essentially, you compare your position to a more commonly known one and make your argument through the comparison. For example, in the “Trust No One” argument above, the author equates the Watergate and Monica Lewinsky scandals. Since it is common knowledge that Watergate was a serious scandal, including Monica Lewinsky in the list offers a strong argument by analogy: the Lewinsky scandal did as much damage as Watergate. To break this rule, you might make an analogy that does not hold up, such as comparing a minor scandal involving a local school board to Watergate. This would be an exaggeration, in most cases.

8. The Validity Rule

“The reasoning in the argumentation must be logically valid or must be capable of being made valid by making explicit one or more unexpressed premises” (132).

This rule is about traditional logics. Violating this rule means that the parts of your argument do not match up. For example, your cause and effect might be off: If you swim in the ocean today you will get stung by a jelly fish and need medical care. Joe went to the doctor today. He must have been stung by a jelly fish. While this example is obvious (we do not know that Joe went swimming), many argument problems are caused by violating this rule.

9. The Closure Rule

“A failed defense of a standpoint must result in the protagonist retracting the standpoint, and a successful defense of a standpoint must result in the antagonist retracting his or her doubts” (134).

This seems the most obvious rule, yet it is one that most public arguments ignore. If your argument does not cut it, admit the faults and move on. If another writer/speaker offers a rebuttal and you clearly counter it, admit that the original argument is sound. Seems simple, but it’s not in our public culture. This would mean that George W. Bush would have to have a press conference and say, “My apologies, I was wrong about WMD,” or for someone who argued fervently that Americans want a single payer option for healthcare to instead argue something like, “The polls show that American’s want to change healthcare, but not through the single payer option. My argument was based on my opinion that single payer is the best way and not on public opinion.” Academics are more accustomed to retraction because our arguments are explicitly part of particular conversations. Rebuttals and renegotiations are the norm. That does not make them any easier to stomach in an “argument is war” culture.

10. The Usage Rule

“Parties must not use any formulations that are insufficiently clear or confusingly ambiguous, and they must interpret the formulations of the other party as carefully and accurately as possible” (136).

While academics are perhaps the worst violators of this rule, it is an important one to discuss. Be clear. I notice in both student and professional academic writing that a confusing concept often means confusing prose, longer sentences, and more letters in a word. If you cannot say it/write it clearly, the concept might not yet be clear to you. Keep working. Ethical violations of this rule happen when someone is purposefully ambiguous so as to confuse the issue. We can see this on all the “law” shows on television or though deliberate propaganda.

Activity: Following the Rules

Choose a topic to discuss in class or as a group (ex. organic farming, campus parking, gun control).

- Choose one of the rules above and write a short argument (a sentence) that clearly violates the rule. Be prepared to explain WHY it violates the rule.

- Take the fallacious argument you just created in exercise a) and correct it. Write a solid argument that conforms to the rule.

Food for thought: The above rules offer one way to think about shaping an argument paper. Imagine that the argument for your next paper is a dialogue between those who disagree about your topic. After doing research, write out the primary standpoint for your paper. For example: organic farming is a sustainable practice that should be used more broadly. Next, write out a standpoint that might offer a refutation of the argument. For example: organic farming cannot supply all of the food needed by the world’s population. Once you have a sense of your own argument and possible refutations, go through the rules and imagine how you might ethically and clearly provide arguments that support your point without ignoring the opposition.

Even though our current media and political climate do not call for good argumentation, the guidelines for finding and creating it abound. There are many organizations such as America Speaks (www. americaspeaks.org) that are attempting to revive quality, ethical deliberation. On the personal level, each writer can be more deliberate in their argumentation by choosing to follow some of these methodical approaches to ensure the soundness and general quality of their argument. The above models offer the possibility that we can imagine modes of argumentation other than war. The final model, pragma-dialectics, especially, seems to consider argument as a conversation that requires constant vigilance and interaction by participants. Argument as conversation, as new metaphor for public deliberation, has possibilities.

Additional Activities

- Read Stanley Fish’s blog entry titled “Democracy and Education” (http://fish.blogs.nytimes.com/2007/07/22/democracy-andeducation/#more-57). Choose at least two of the responses to Fish’s argument that students are not entitled to free speech rights in the classroom and compare them using the different argumentation models listed above.

- Following the pragma-dialectic rules, create a fair and balanced rebuttal to Fish’s argument in his “Democracy and Education” blog entry.

- Use Toulmin’s vocabulary to build an argument. Start with a claim and then fill in the chart with your own research, warrants, qualifiers, and rebuttals.

Note

1. I would like to extend a special thanks to Nina Paley for giving permission to use this cartoon under Creative Commons licensing, free of charge. Please see Paley’s great work at www.ninapaley.com.

Works Cited

Coulter, Ann. Guilty: Liberal “Victims” and Their Assault on America. New York: Crown Forum, 2009. Print.

Crowley, Sharon, and Debra Hawhee. Ancient Rhetorics for Contemporary Students. 4th ed. New York: Pearson/Longman, 2009. Print.

Eemeren, Frans H. van, and Rob Grootendorst. Fundamentals of Argumentation Theory: A Handbook of Historical Backgrounds and Contemporary Developments. Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum, 1996. Print.

Eemeren, Frans H. van, Rob Grootendorst, and Francesca Snoeck Henkemans. Argumentation: Analysis, Evaluation, Presentation. Mahwah: Erlbaum, NJ: 2002. Print.

Fish, Stanley. “Democracy and Education.” New York Times 22 July 2007: n. pag. Web. 5 May 2010. <http://fish.blogs.nytimes.com/2007/07/22/ democracy-and-education/>.

Honeycutt, Lee. “Aristotle’s Rhetoric: A Hypertextual Resource Compiled by Lee Honeycutt.” 21 June 2004. Web. 5 May 2010. <http://www2. iastate.edu/~honeyl/Rhetoric/index.html>.

Lakoff, George, and Mark Johnson. Metaphors We Live By. Chicago: U of Chicago P, 1980. Print.

Murphy, James. Quintilian On the Teaching and Speaking of Writing. Carbondale: Southern Illinois UP, 1987. Print.

Paxton, Pamela, and Jeremy Adam Smith. “Not Everyone Is Out to Get You.” UTNE Reader Sept.-Oct. 2009: 44-45. Print.

“Plato, The Dialogues of Plato, vol. 1 [387 AD].” Online Library of Liberty, n. d. Web. 5 May 2010. <http://oll.libertyfund.org/index.php?option=com_ staticxt&staticfile=show.php%3Ftitle=111&layout=html#chapt er_39482>.