27 Critical Thinking in College Writing: From the Personal to the Academic

Gita DasBender

There is something about the term “critical thinking” that makes you draw a blank every time you think about what it means. It seems so fuzzy and abstract that you end up feeling uncomfortable, as though the term is thrust upon you, demanding an intellectual effort that you may not yet have. But you know it requires you to enter a realm of smart, complex ideas that others have written about and that you have to navigate, understand, and interact with just as intelligently. It’s a lot to ask for. It makes you feel like a stranger in a strange land.

As a writing teacher I am accustomed to reading and responding to difficult texts. In fact, I like grappling with texts that have interesting ideas no matter how complicated they are because I understand their value. I have learned through my years of education that what ultimately engages me, keeps me enthralled, is not just grammatically pristine, fluent writing, but writing that forces me to think beyond the page. It is writing where the writer has challenged herself and then offered up that challenge to the reader, like a baton in a relay race. The idea is to run with the baton.

You will often come across critical thinking and analysis as requirements for assignments in writing and upper-level courses in a variety of disciplines. Instructors have varying explanations of what they actually require of you, but, in general, they expect you to respond thoughtfully to texts you have read. The first thing you should remember is not to be afraid of critical thinking. It does not mean that you have to criticize the text, disagree with its premise, or attack the writer simply because you feel you must. Criticism is the process of responding to and evaluating ideas, argument, and style so that readers understand how and why you value these items.

Critical thinking is also a process that is fundamental to all disciplines. While in this essay I refer mainly to critical thinking in composition, the general principles behind critical thinking are strikingly similar in other fields and disciplines. In history, for instance, it could mean examining and analyzing primary sources in order to understand the context in which they were written. In the hard sciences, it usually involves careful reasoning, making judgments and decisions, and problem solving. While critical thinking may be subject-specific, that is to say, it can vary in method and technique depending on the discipline, most of its general principles such as rational thinking, making independent evaluations and judgments, and a healthy skepticism of what is being read, are common to all disciplines. No matter the area of study, the application of critical thinking skills leads to clear and flexible thinking and a better understanding of the subject at hand.

To be a critical thinker you not only have to have an informed opinion about the text but also a thoughtful response to it. There is no doubt that critical thinking is serious thinking, so here are some steps you can take to become a serious thinker and writer.

Attentive Reading: A Foundation for Critical Thinking

A critical thinker is always a good reader because to engage critically with a text you have to read attentively and with an open mind, absorbing new ideas and forming your own as you go along. Let us imagine you are reading an essay by Annie Dillard, a famous essayist, called “Living like Weasels.” Students are drawn to it because the idea of the essay appeals to something personally fundamental to all of us: how to live our lives. It is also a provocative essay that pulls the reader into the argument and forces a reaction, a good criterion for critical thinking.

So let’s say that in reading the essay you encounter a quote that gives you pause. In describing her encounter with a weasel in Hollins Pond, Dillard says, “I would like to learn, or remember, how to live . . . I don’t think I can learn from a wild animal how to live in particular . . . but I might learn something of mindlessness, something of the purity of living in the physical senses and the dignity of living without bias or motive” (220). You may not be familiar with language like this. It seems complicated, and you have to stop ever so often (perhaps after every phrase) to see if you understood what Dillard means. You may ask yourself these questions:

- What does “mindlessness” mean in this context?

- How can one “learn something of mindlessness?”

- What does Dillard mean by “purity of living in the physical senses?”

- How can one live “without bias or motive?”

These questions show that you are an attentive reader. Instead of simply glossing over this important passage, you have actually stopped to think about what the writer means and what she expects you to get from it. Here is how I read the quote and try to answer the questions above: Dillard proposes a simple and uncomplicated way of life as she looks to the animal world for inspiration. It is ironic that she admires the quality of “mindlessness” since it is our consciousness, our very capacity to think and reason, which makes us human, which makes us beings of a higher order. Yet, Dillard seems to imply that we need to live instinctually, to be guided by our senses rather than our intellect. Such a “thoughtless” approach to daily living, according to Dillard, would mean that our actions would not be tainted by our biases or motives, our prejudices. We would go back to a primal way of living, like the weasel she observes. It may take you some time to arrive at this understanding on your own, but it is important to stop, reflect, and ask questions of the text whenever you feel stumped by it. Often such questions will be helpful during class discussions and peer review sessions.

Listing Important Ideas

When reading any essay, keep track of all the important points the writer makes by jotting down a list of ideas or quotations in a notebook. This list not only allows you to remember ideas that are central to the writer’s argument, ideas that struck you in some way or the other, but it also you helps you to get a good sense of the whole reading assignment point by point. In reading Annie Dillard’s essay, we come across several points that contribute toward her proposal for better living and that help us get a better understanding of her main argument. Here is a list of some of her ideas that struck me as important:

- “The weasel lives in necessity and we live in choice, hating necessity and dying at the last ignobly in its talons” (220).

- “And I suspect that for me the way is like the weasel’s: open to time and death painlessly, noticing everything, remembering nothing, choosing the given with a fierce and pointed will” (221).

- “We can live any way we want. People take vows of poverty, chastity, and obedience—even of silence—by choice. The thing is to stalk your calling in a certain skilled and supple way, to locate the most tender and live spot and plug into that pulse” (221).

- “A weasel doesn’t ‘attack’ anything; a weasel lives as he’s meant to, yielding at every moment to the perfect freedom of single necessity” (221).

- “I think it would be well, and proper, and obedient, and pure, to grasp your one necessity and not let it go, to dangle from it limp wherever it takes you” (221).

These quotations give you a cumulative sense of what Dillard is trying to get at in her essay, that is, they lay out the elements with which she builds her argument. She first explains how the weasel lives, what she learns from observing the weasel, and then prescribes a lifestyle she admires—the central concern of her essay.

Noticing Key Terms and Summarizing Important Quotes

Within the list of quotations above are key terms and phrases that are critical to your understanding of the ideal life as Dillard describes it. For instance, “mindlessness,” “instinct,” “perfect freedom of a single necessity,” “stalk your calling,” “choice,” and “fierce and pointed will” are weighty terms and phrases, heavy with meaning, that you need to spend time understanding. You also need to understand the relationship between them and the quotations in which they appear. This is how you might work on each quotation to get a sense of its meaning and then come up with a statement that takes the key terms into account and expresses a general understanding of the text:

Quote 1: Animals (like the weasel) live in “necessity,” which means that their only goal in life is to survive. They don’t think about how they should live or what choices they should make like humans do. According to Dillard, we like to have options and resist the idea of “necessity.” We fight death—an inevitable force that we have no control over—and yet ultimately surrender to it as it is the necessary end of our lives.

Quote 2: Dillard thinks the weasel’s way of life is the best way to live. It implies a pure and simple approach to life where we do not worry about the passage of time or the approach of death. Like the weasel, we should live life in the moment, intensely experiencing everything but not dwelling on the past. We should accept our condition, what we are “given,” with a “fierce and pointed will.” Perhaps this means that we should pursue our one goal, our one passion in life, with the same single-minded determination and tenacity that we see in the weasel.

Quote 3: As humans, we can choose any lifestyle we want. The trick, however, is to go after our one goal, one passion like a stalker would after a prey.

Quote 4: While we may think that the weasel (or any animal) chooses to attack other animals, it is really only surrendering to the one thing it knows: its need to live. Dillard tells us there is “the perfect freedom” in this desire to survive because toher, the lack of options (the animal has no other option than to fight to survive) is the most liberating of all.

Quote 5: Dillard urges us to latch on to our deepest passion in life (the “one necessity”) with the tenacity of a weasel and not let go. Perhaps she’s telling us how important it is to have an unwavering focus or goal in life.

Writing a Personal Response: Looking Inward

Dillard’s ideas will have certainly provoked a response in your mind, so if you have some clear thoughts about how you feel about the essay this is the time to write them down. As you look at the quotes you have selected and your explanation of their meaning, begin to create your personal response to the essay. You may begin by using some of these strategies:

- Tell a story. Has Dillard’s essay reminded you of an experience you have had? Write a story in which you illustrate a point that Dillard makes or hint at an idea that is connected to her essay.

- Focus on an idea from Dillard’s essay that is personally important to you. Write down your thoughts about this idea in a first person narrative and explain your perspective on the issue.

- If you are uncomfortable writing a personal narrative or using “I” (you should not be), reflect on some of her ideas that seem important and meaningful in general. Why were you struck by these ideas?

- Write a short letter to Dillard in which you speak to her about the essay. You may compliment her on some of her ideas by explaining why you like them, ask her a question related to her essay and explain why that question came to you, and genuinely start up a conversation with her.

This stage in critical thinking is important for establishing your relationship with a text. What do I mean by this “relationship,” you may ask? Simply put, it has to do with how you feel about the text. Are you amazed by how true the ideas seem to be, how wise Dillard sounds? Or are you annoyed by Dillard’s let-me-tell-you-how-to-live approach and disturbed by the impractical ideas she so easily prescribes? Do you find Dillard’s voice and style thrilling and engaging or merely confusing? No matter which of the personal response options you select, your initial reaction to the text will help shape your views about it.

Making an Academic Connection: Looking Outward

First year writing courses are designed to teach a range of writing— from the personal to the academic—so that you can learn to express advanced ideas, arguments, concepts, or theories in any discipline. While the example I have been discussing pertains mainly to college writing, the method of analysis and approach to critical thinking I have demonstrated here will serve you well in a variety of disciplines. Since critical thinking and analysis are key elements of the reading and writing you will do in college, it is important to understand how they form a part of academic writing. No matter how intimidating the term “academic writing” may seem (it is, after all, associated with advanced writing and becoming an expert in a field of study), embrace it not as a temporary college requirement but as a habit of mind.

To some, academic writing often implies impersonal writing, writing that is detached, distant, and lacking in personal meaning or relevance. However, this is often not true of the academic writing you will do in a composition class. Here your presence as a writer—your thoughts, experiences, ideas, and therefore who you are—is of much significance to the writing you produce. In fact, it would not be farfetched to say that in a writing class academic writing often begins with personal writing. Let me explain. If critical thinking begins with a personal view of the text, academic writing helps you broaden that view by going beyond the personal to a more universal point of view. In other words, academic writing often has its roots in one’s private opinion or perspective about another writer’s ideas but ultimately goes beyond this opinion to the expression of larger, more abstract ideas. Your personal vision—your core beliefs and general approach to life— will help you arrive at these “larger ideas” or universal propositions that any reader can understand and be enlightened by, if not agree with. In short, academic writing is largely about taking a critical, analytical stance toward a subject in order to arrive at some compelling conclusions.

Let us now think about how you might apply your critical thinking skills to move from a personal reaction to a more formal academic response to Annie Dillard’s essay. The second stage of critical thinking involves textual analysis and requires you to do the following:

- Summarize the writer’s ideas the best you can in a brief paragraph. This provides the basis for extended analysis since it contains the central ideas of the piece, the building blocks, so to speak.

- Evaluate the most important ideas of the essay by considering their merits or flaws, their worthiness or lack of worthiness. Do not merely agree or disagree with the ideas but explore and explain why you believe they are socially, politically, philosophically, or historically important and relevant, or why you need to question, challenge, or reject them.

- Identify gaps or discrepancies in the writer’s argument. Does she contradict herself? If so, explain how this contradiction forces you to think more deeply about her ideas. Or if you are confused, explain what is confusing and why.

- Examine the strategies the writer uses to express her ideas. Look particularly at her style, voice, use of figurative language, and the way she structures her essay and organizes her ideas. Do these strategies strengthen or weaken her argument? How?

- Include a second text—an essay, a poem, lyrics of a song— whose ideas enhance your reading and analysis of the primary text. This text may help provide evidence by supporting a point you’re making, and further your argument.

- Extend the writer’s ideas, develop your own perspective, and propose new ways of thinking about the subject at hand.

Crafting the Essay

Once you have taken notes and developed a thorough understanding of the text, you are on your way to writing a good essay. If you were asked to write an exploratory essay, a personal response to Dillard’s essay would probably suffice. However, an academic writing assignment requires you to be more critical. As counter-intuitive as it may sound, beginning your essay with a personal anecdote often helps to establish your relationship to the text and draw the reader into your writing. It also helps to ease you into the more complex task of textual analysis. Once you begin to analyze Dillard’s ideas, go back to the list of important ideas and quotations you created as you read the essay. After a brief summary, engage with the quotations that are most important, that get to the heart of Dillard’s ideas, and explore their meaning. Textual engagement, a seemingly slippery concept, simply means that you respond directly to some of Dillard’s ideas, examine the value of Dillard’s assertions, and explain why they are worthwhile or why they should be rejected. This should help you to transition into analysis and evaluation. Also, this part of your essay will most clearly reflect your critical thinking abilities as you are expected not only to represent Dillard’s ideas but also to weigh their significance. Your observations about the various points she makes, analysis of conflicting viewpoints or contradictions, and your understanding of her general thesis should now be synthesized into a rich new idea about how we should live our lives. Conclude by explaining this fresh point of view in clear, compelling language and by rearticulating your main argument.

Modeling Good Writing

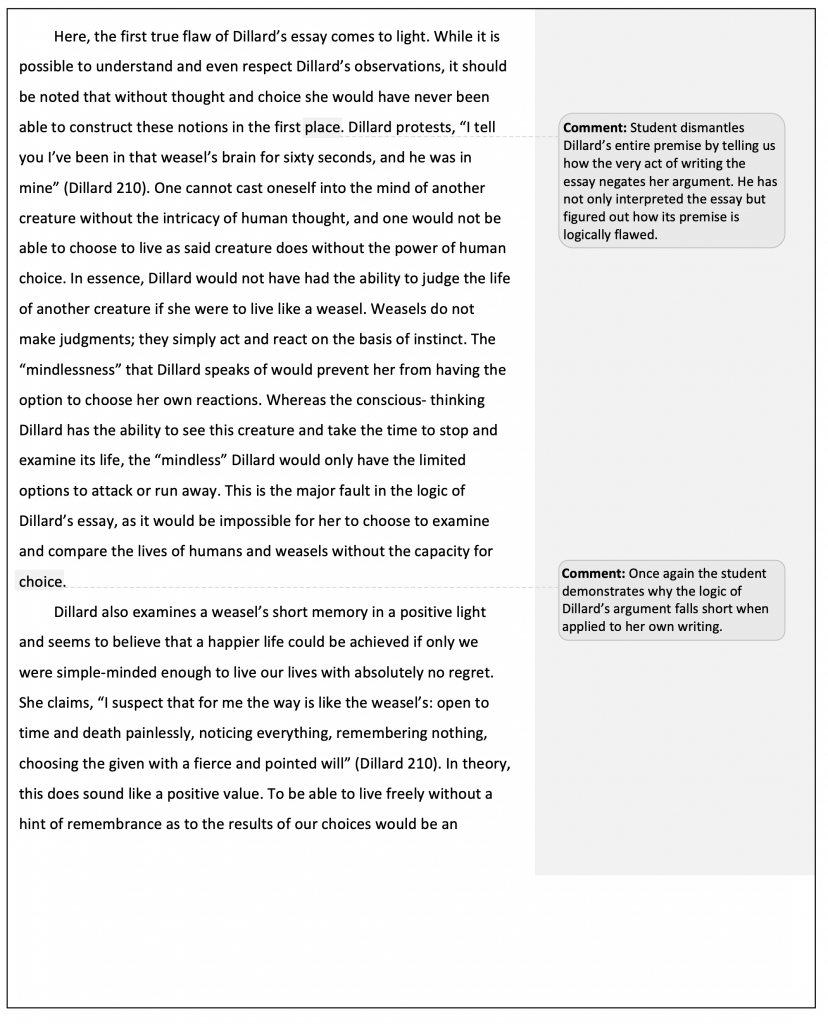

When I teach a writing class, I often show students samples of really good writing that I’ve collected over the years. I do this for two reasons: first, to show students how another freshman writer understood and responded to an assignment that they are currently working on; and second, to encourage them to succeed as well. I explain that although they may be intimidated by strong, sophisticated writing and feel pressured to perform similarly, it is always helpful to see what it takes to get an A. It also helps to follow a writer’s imagination, to learn how the mind works when confronted with a task involving critical thinking. The following sample is a response to the Annie Dillard essay. Figure 1 includes the entire student essay and my comments are inserted into the text to guide your reading.

Though this student has not included a personal narrative in his essay, his own world-view is clear throughout. His personal point of view, while not expressed in first person statements, is evident from the very beginning. So we could say that a personal response to the text need not always be expressed in experiential or narrative form but may be present as reflection, as it is here. The point is that the writer has traveled through the rough terrain of critical thinking by starting out with his own ruminations on the subject, then by critically analyzing and responding to Dillard’s text, and finally by developing a strong point of view of his own about our responsibility as human beings. As readers we are engaged by clear, compelling writing and riveted by critical thinking that produces a movement of ideas that give the essay depth and meaning. The challenge Dillard set forth in her essay has been met and the baton passed along to us.

Exercises

Discussion

- Write about your experiences with critical thinking assignments. What seemed to be the most difficult? What approaches did you try to overcome the difficulty?

- Respond to the list of strategies on how to conduct textual analysis. How well do these strategies work for you? Add your own tips to the list.

- Evaluate the student essay by noting aspects of critical thinking that are evident to you. How would you grade this essay? What other qualities (or problems) do you notice?

Works Cited

Dillard, Annie. “Living like Weasels.” One Hundred Great Essays. Ed. Robert DiYanni. New York: Longman, 2002. 217–221. Print.