3 What is a “Good Writer”?

Thinking Comes First

The Myth of “Bad Writers”

Many students tell themselves that they are bad at writing, but too often that conclusion is based on surface-level issues like grammar and punctuation. While mechanical errors matter, strong writing goes far beyond avoiding comma mistakes. A good writer is, first and foremost, a good thinker—but good thinking alone isn’t enough. You also need to communicate your ideas clearly, organize them effectively, and engage your reader. Writing is a skill that develops through practice, revision, and persistence. The goal of this course is not just to help you write better essays, but to help you become a stronger communicator overall.

Why Writing is Thinking

Writing is integral to critical thinking. It is a way to facilitate critical thinking, and it is also a way of demonstrating critical thinking. Let’s discuss each of those.

How Writing Facilitates Critical Thinking

As an undergraduate student, I had a class about assessment. For a group project, we performed an experiment. First, we gave a group of people a topic to write about. We gave them one minute to think about the topic and then a couple of minutes to write. We gave a second group the same topic but instead of asking them to simply think about the topic for one minute, we asked them to use that one minute to write notes. Then they had a couple of minutes to write. The second group wrote significantly more, and they had better formulated and more interesting ideas.

What we learned was that those who just thought about the topic found their first good idea and then spent the rest of the minute trying to remember it rather than coming up with additional ideas. The second group wrote down the idea, which allowed them to continue thinking of additional ideas. This exercise was very enlightening for me as an undergraduate student, so much so that I’ve shared it with hundreds of students since then. Writing down our ideas is a way of giving ourselves permission to stop repeating the idea and instead build on the idea or move on to additional ideas.

How Writing Demonstrates Critical Thinking

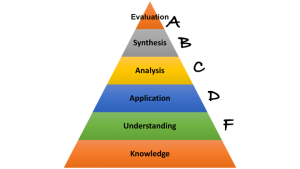

Another experience I had as an undergraduate student was getting my first D on an essay. I’d never scored less than a B on any paper in high school or college, and this particular paper didn’t seem much different than all the others, but my instructor had drawn Bloom’s Taxonomy on the paper (which I did not know what was at the time) and had labeled the levels:

- Evaluation (A)

- Synthesis (B)

- Analysis (C)

- Application (D)

- Understanding (F)

I worked a lot harder in that class the rest of the semester and did okay, but I didn’t fully understand until working on my master’s degree and developing a better understanding of Bloom’s Taxonomy what he was really looking for. He was grading based on the level of critical thinking demonstrated in the essay, not my ability to write a paragraph, use correct grammar, or even have a good thesis statement.

I eventually realized that was the goal in every class. While teachers sometimes grade based on mechanics, what they are really looking for is critical thinking. To be a good writer at the college level, the most important skill is critical thinking.

The Levels of Critical Thinking in Writing

There is a more current version of Bloom’s taxonomy, but in this class, I use the old version with “evaluation” at the top because it fits the purposes of this class better. Below is an outline to help you understand the levels of Bloom’s Taxonomy and how they apply to writing an essay.

Knowledge and Understanding (Lowest Levels of Bloom’s Taxonomy)

As long as you can talk about the topic, you are demonstrating knowledge and understanding. You’ve been developing your ability to demonstrate knowledge and understanding in writing since elementary school with your first book reports. In elementary school, the ability to demonstrate knowledge and understanding is worth an A. In college, if this is the extent of the critical thinking demonstrated in your writing, it’s worth an F.

Application (3rd Level of Bloom’s Taxonomy)

Application is your ability to make basic connections about your information or to use your information to get to the next step. “What does that have to do with…” is a prompt for application. Application in an essay can be demonstrated by connecting paragraphs to the thesis statement or using transitions to connect paragraphs to each other. Application might recognize chronological order, cause and effect, or other simple comparisons. Your ability to do this in middle school would get you an A on a paper because it can result in a perfect five-paragraph essay. At the college level, if you are only demonstrating application, you are likely to get a D.

Analysis (4th Level of Bloom’s Taxonomy – First Level of Higher-Order Thinking)

Analysis is breaking a topic into smaller parts and looking closely at the individual parts to find deeper meaning in the whole. Asking “why” questions about your topic to help you dig deeper is a way of using analysis. You started working on this skill in middle school when learning about metaphors, similes, and symbols. Those exercises help you look at individual pieces of the subject and see added meaning. You probably weren’t expected to use this skill well until early high school. If you could demonstrate analysis in high school, you probably got an A. In college, if you stop at this level, you are likely to get a C.

Synthesis (5th Level of Bloom’s Taxonomy – Second Level of Higher-Order Thinking)

Synthesis is looking beyond the individual topic and using additional sources to draw new conclusions. Where analysis is like studying an individual puzzle piece, synthesis is like putting multiple puzzle pieces together to see a bigger picture. You were likely expected to start using some sources in high school. Simply using sources in your essay may or may not demonstrate synthesis, but that was the goal. If you put your sources together in a way that the combination builds a bigger picture, you have demonstrated synthesis. If you could do this in high school, you probably got an A on your paper and maybe even some additional praise. In college, this level will get you a B.

Evaluation (Top Level of Bloom’s Taxonomy)

If you use synthesis really well, you almost can’t help but demonstrate evaluation too. Evaluation is basically drawing new conclusions. It’s more than just a judgment. Your teachers may have used the word evaluation in your elementary book reports where you just had to decide whether or not you liked the book, but that’s just a judgment.

For the evaluation level of critical thinking, you need to have demonstrated all the levels below it, which should build on each other and work toward a conclusion. By putting the pieces of the puzzle together, you can see a picture that was not discernible with just a few pieces. Stating what that bigger picture is demonstrates evaluation, and then you use all the other levels to explain it. Evaluation is best demonstrated in an essay through the thesis statement and the conclusion paragraph, which is why those two areas of an essay are often the most difficult for students to write. This is the “college level” of writing to earn an A.

Moving Beyond the Basics: Writing for College-Level Success

Good writing isn’t just about avoiding grammar mistakes—it’s about thinking critically and presenting ideas in a way that demonstrates deep understanding. To be a strong writer, you must learn to move beyond surface-level responses and engage with ideas on a more meaningful level. The strongest writers don’t just report information; they analyze, synthesize, and evaluate it to create something new. That’s the key to writing success in college and beyond.

Communicate Your Thoughts!

Organization and Conciseness

To be a good writer, you must first be a good thinker. Sometimes getting those thoughts outside of our head so that others can see them can be difficult. In addition to the brilliant ideas, you must be able to communicate it effectively in the required form. In this class, the form will be an essay.

As you write, if your ideas are disorganized or buried under unnecessary words, even strong critical thinking won’t come across effectively. A well-organized essay guides the reader, helping them follow your argument without confusion.

Conciseness is another essential element of good writing. Many students assume that more words make writing sound smarter, but in reality, extra words can weaken an argument. Strong writing is direct, precise, and intentional.

If you’re unsure whether your writing is clear, try reading your work aloud. If you get lost, your reader likely will too. Pay attention to transitions, sentence structure, and wordiness—these small refinements can make a big difference in how your ideas come across. This book will introduce you to these and other strategies to help strengthen your writing.

Revision and Persistence

Many students assume good writers create strong essays in one try, but the reality is that all great writing is rewritten. First drafts are just that—first attempts. Even the best writers refine, restructure, and rethink their work multiple times.

Think of revision as part of the thinking process rather than just a way to fix mistakes. As you revise, you might realize your thesis needs to be stronger or that an argument needs more support. Each round of revision makes your writing clearer, stronger, and more persuasive.

Rather than seeing revision as a chore, try to view it as an opportunity to sharpen your ideas. If a professor gives feedback, don’t just make surface-level changes—dig into the reasoning behind their suggestions and use them to push your thinking further.

Voice and Engagement

Writing isn’t just about presenting information—it’s also about engaging your reader. A strong writer develops a voice, a sense of personality and style that makes their writing distinct. This doesn’t mean every essay should be informal, but it does mean your writing should feel natural and confident rather than robotic or forced.

One way to develop voice is to write with genuine interest. If you find a way to connect with your topic, your writing will feel more authentic. Readers, including professors, can tell when a writer is just going through the motions versus when they are truly invested in their argument.

A good writer balances academic rigor with readability. Even in a formal essay, engaging writing keeps the reader interested and makes complex ideas easier to digest. Avoid filler, stay focused, and let your thinking shine through.

Estimated Reading Time: 12 minutes