Learning Objectives

Understand how to develop and organize content in patterns that are appropriate for your document and audience.

Demonstrate your ability to order, outline, and emphasize main points in one or more written assignments.

Demonstrate how to compose logically organized paragraphs, sentences, and transitions in one or more written assignments.

The purpose of business writing is to communicate facts and ideas. In order to accomplish that purpose, each document has key components that need to be present in order for your reading audience to understand the message. These elements may seem simple to the point that you may question how any writer could neglect them. But if you take note of how often miscommunication and misunderstanding happen, particularly in written communications, you will realize that it happens all the time. Omission or neglect may be intentional, but it is often unintentional; the writer assumes (wrongly) that the reader will easily understand a concept, idea, or the meaning of the message. From background to language, culture to education, there are many variables that come into play and make effective communication a challenge. The degree to which you address these basic elements will increase the effectiveness of your documents. Each document must address the following:

- Who

- What

- When

- Where

- How

- (And sometimes) Why

If you have these elements in mind as you prepare your document, it will be easier to decide what to write and in what order. They will also be useful when you are reviewing your document before delivering it. If your draft omits any of these elements or addresses it unclearly, you will know what you need to do to fix it.

Another way to approach organizing your document is with the classical proofs known as ethos, logos, and pathos. Ethos, or your credibility, will come through with your choice of sources and authority on the subject(s). Your logos, or the logic of your thoughts represented across the document, will allow the reader to come to understand the relationships among who, what, where, when, and so forth. If your readers cannot follow your logic, they will lose interest, fail to understand your message, and possibly not even read it at all. Finally, your design and word choices will reflect your pathos, passion, and enthusiasm. If your document fails to convey enthusiasm for the subject, how can you expect the reader to be interested? Every document, indeed every communication, represents aspects of these classical elements.

General Purpose and Thesis Statements

Whatever your business writing project involves, it must convey some central idea. Write a thesis statement to clarify the idea in your mind and make sure it comes through to your audience. A thesis statement, or central idea, should be short, specific, and to the point. Steven Beebe and Susan Beebe (1997) recommend five guiding principles when considering your thesis statement. The thesis statement should

- be a declarative statement;

- be a complete sentence;

- use specific language, not vague generalities;

- be a single idea;

- reflect consideration of the audience.

This statement is key to the success of your document. If your audience has to work to find out what exactly you are talking about or what your stated purpose or goal is, they will be less likely to read, be influenced, or recall what you have written. By stating your point clearly in your introduction and then referring back to it in the body of the document and at the end, you will help your readers understand and remember your message.

Organizing Principles

Once you know the basic elements of your message, you need to decide in what order to present them to your audience. A central organizing principle will help you determine a logical order for your information. One common organizing principle is chronology or time: the writer tells what happened first, then what happened next, then what is happening now, and, finally, what is expected to happen in the future. Another common organizing principle is comparison: the writer describes one product, an argument on one side of an issue, or one possible course of action and then compares it with another product, argument, or course of action.

For example, let’s imagine that you are a business writer within the transportation industry and have been assigned to write a series of informative pieces about an international initiative called the “TransAmerica Transportation System Study.” Just as the First Transcontinental Railroad once unified the United States from east to west, which the Interstate further reinforced with the Highway System, the proposed TransAmerica Transportation System will facilitate integrating the markets of Mexico, the United States, and Canada from north to south. Rail transportation has long been an integral part of the transportation and distribution system for goods across the Americas, and its role will be important in this new system.

In deciding how to organize your report, you have several challenges and many possibilities for using different organizing principles. Part of your introduction will involve a historical perspective and a discussion of the events that led from the First Transcontinental Railroad to the TransAmerica Transportation System proposal. Other aspects will include comparing the old railroad and highway systems to the new ones and the transformative effect this will have on business and industry. You will need to acknowledge the complex relationships and challenges that collaboration has overcome and highlight the common benefits. You will be called on to write informative documents as part of a public relations initiative, persuasive essays to underscore the benefits for those who prefer the status quo, and even write speeches for celebrations and awards.

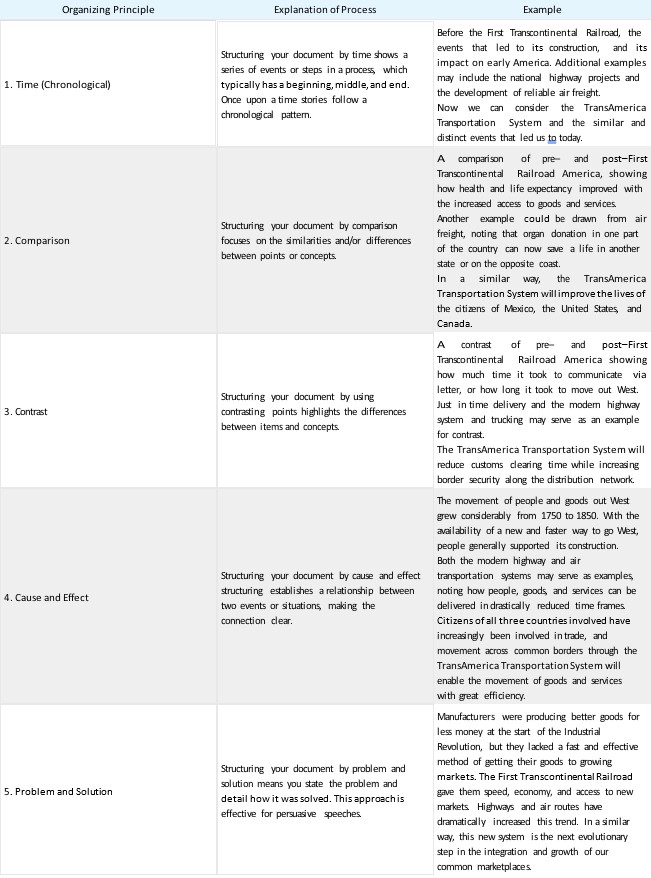

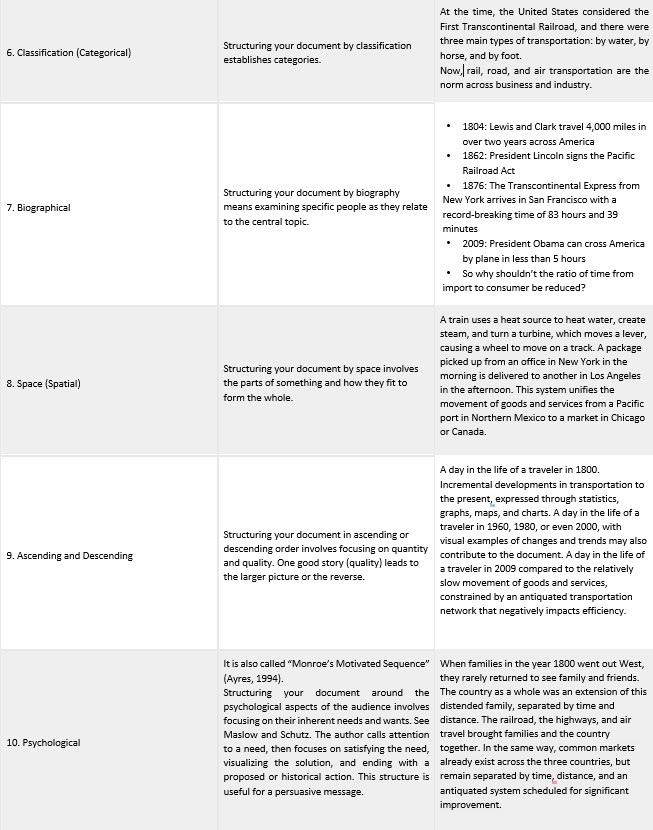

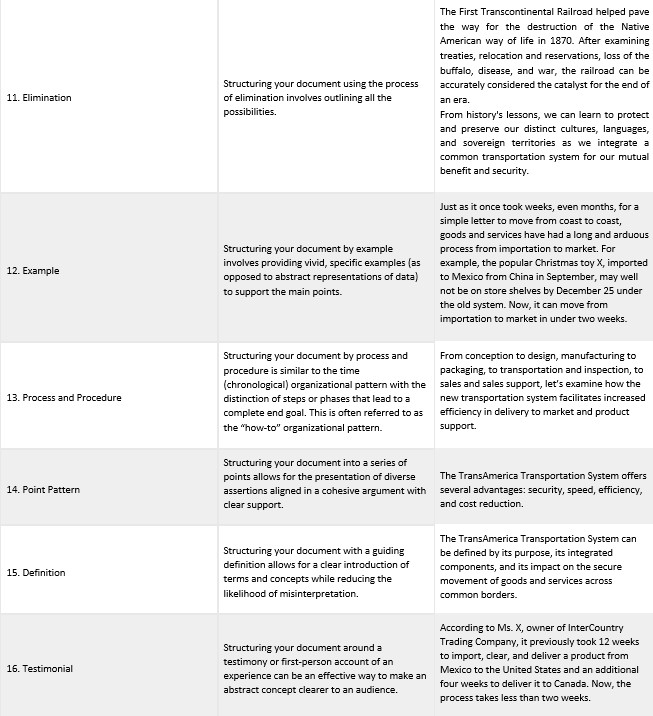

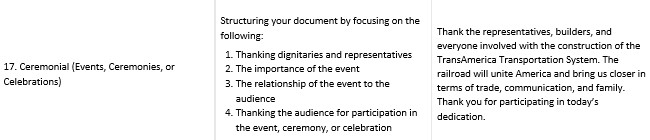

Table 6.1.1 lists seventeen different organizing principles and how they might be applied to various pieces you would write about the TransAmerica Transportation System. The left column provides the name of the organizing principle. The center column explains the process of organizing a document according to each principle, and the third column provides an example.

Outlines

Chances are you have learned the basic principles of outlining in English writing courses: an outline is a framework that organizes main ideas, subordinate ideas, and sub-subpoints in a hierarchical series of Roman numerals, alphabetical letters, and bullet points.

According to Winans (1917), following the principle of unity should help your outline adhere to the principle of coherence, which states that there should be a logical and natural flow of ideas, with main points, subpoints, and sub-subpoints connecting to each other. Shorter phrases and keywords can make up the speaking outline, but you should write complete sentences throughout your formal outline to ensure coherence. Furthermore, the principle of emphasis states that the material included in your outline should be engaging and balanced (Winans, 1917). As you place supporting material into your outline, choose the information that will impact your audience most. Choose proxemic and relevant information, meaning that it can be easily related to the audience’s lives because it matches their interests or ties into current events or the local area. Also, make sure your information is balanced. The outline serves as a useful visual representation of the proportions of your speech. You can tell by how much space a main point, subpoint, or sub-subpoint takes up in relation to other points of the same level and whether or not your speech is balanced.

If one subpoint is half a page, but the main point is only a quarter of a page, then you may want to consider making the subpoint a main point. Each part of your speech doesn’t have to be equal. The first or last point may be more substantial than a middle point if you are following primacy or recency, but overall the speech should be relatively balanced.

Paragraphs

Paragraphs are how we package information in business communication, and the more efficient the package, the easier the meaning can be delivered.

You may wish to think of each paragraph as a small essay within a larger information platform, defined by a guiding thesis and an organizing principle. The standard five-paragraph essay format used on college term papers is mirrored in individual paragraphs. Often, college essays have minimum or maximum word counts, but paragraphs hardly ever have established limits. Each paragraph focuses on one central idea. It can be as long or as short as it needs to be to get the message across, but remember your audience and avoid long, drawn-out paragraphs that may lose your reader’s attention.

Just as a document generally has an introduction, body, and conclusion, so does a paragraph. Each paragraph has one idea, thought, or purpose that is stated in an introductory sentence. One or more supporting sentences follow this, conclude with a summary statement, and transition or link to the next idea or paragraph. Let’s address each in turn:

The topic sentence states the main thesis, purpose, or topic of the paragraph; it defines the subject matter to be addressed in that paragraph.

Body sentences support the topic sentence and relate clearly to the subject matter of the paragraph and overall document. They may use an organizing principle similar to that of the document itself (chronology, contrast, spatial) or introduce a related organizing principle (point by point, process, or procedure).

The conclusion sentence brings the paragraph to a close; it may do this in any of several ways. It may reinforce the paragraph’s main point, summarize the relationships among the body sentences, and/or serve as a transition to the next paragraph.

Effective Sentences

We have talked about the organization of documents and paragraphs, but what about the organization of sentences? You have probably learned in English courses that each sentence needs to have a subject and a verb; most sentences also have an object.

There are four basic types of sentences: declarative, imperative, interrogative, and exclamatory. Here are some examples:

- Declarative – You are invited to join us for lunch.

- Imperative – Please join us for lunch.

- Interrogative – Would you like to join us for lunch?

- Exclamatory – I’m so glad you can join us!

Declarative sentences make a statement, whereas interrogative sentences ask a question. Imperative sentences convey a command, and exclamatory sentences express a strong emotion. Interrogative and exclamatory sentences are easily identified by their final punctuation, a question mark, and an exclamation point, respectively. In business writing, declarative and imperative sentences are more frequently used.

There are also compound and complex sentences, which may use two or more of the four basic types in combination:

- Simple sentence. Sales have increased.

- Compound sentence. Sales have increased, and profits continue to grow.

- Complex sentence. Sales have increased, and we have the sales staff to thank for it.

- Compound complex sentence. Although the economy has been in recession, sales have increased, and we have sales staff to thank for it.

In our simple sentence, “sales” is the subject, and “have increased” is the verb. The sentence can stand alone because it has the two basic parts that constitute a sentence. In our compound sentence, we have two independent clauses that can stand alone; they are joined by the conjunction “and.” In our complex sentence, we have an independent clause, which can stand on its own, combined with a fragment (not a sentence) or dependent clause, which, if it were not joined to the independent clause, would not make any sense. The fragment “and we have the sales staff to thank” on its own would have us asking “for what?” as the subject is absent. Complex compound sentences combine a mix of independent and dependent clauses, and at least one of the clauses must be dependent.

The ability to write complete, correct sentences is like any other skill—it comes with practice. The more writing you do, as you make an effort to use correct grammar, the easier it will become. Reading audiences, particularly in a business context, will not waste their time on poor writing and will move on. Your challenge as an effective business writer is to know what you are going to write and then to make it come across via words, symbols, and images in a clear and concise manner.

Sentences should avoid being vague and focus on specific content. Each sentence should convey a complete thought; a vague sentence fails to meet these criteria. The reader is left wondering what the sentence was supposed to convey.

- Vague –- We can facilitate solutions in pursuit of success by leveraging our core strengths.

- Specific—We can achieve the production targets for the coming quarter by using our knowledge, experience, and capabilities.

Effective sentences also limit the range and scope of each complete thought, avoiding needless complexity. Sometimes, writers mistakenly equate long, complex sentences with excellence and skill. Clear, concise, and often brief sentences communicate ideas and concepts effectively and efficiently that complex, hard-to-follow sentences do not.

- Complex — Air transportation offers speed of delivery in ways few other forms of transportation can match, including tractor-trailer and rail. It is readily available to the individual consumer and the corporate client alike.

- Clear — Air transportation is accessible and faster than railroads or trucking.

Effective sentences are complete, containing a subject and a verb. Incomplete sentences—also known as sentence fragments— demonstrate a failure to pay attention to detail. They often invite misunderstanding, which is the opposite of our goal in business communication.

- Fragments – Although air transportation is fast. Costs more than trucking.

- Complete – Although air transportation is fast, it costs more than trucking.

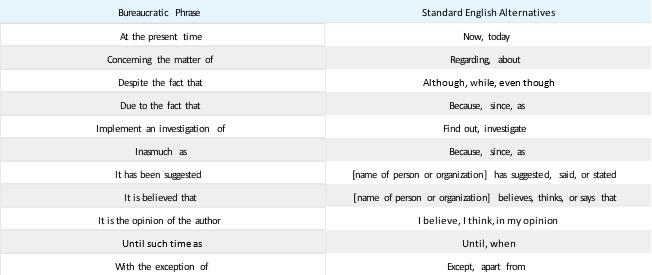

Effective business writing avoids bureaucratic language and phrases that are the hallmark of decoration. Decoration is a reflection of ritual, and ritual has its role. If you are the governor of a state and want to make a resolution declaring today as HIV/AIDS Awareness Day, you are allowed to start the document with “Whereas” because of its ritual importance. Similarly, if you are writing a legal document, tradition calls for certain standard phrases such as “know all men by these presents.” However, in standard business writing, it is best to refrain from using bureaucratic phrases and ritualistic words that decorate and distract the reader from your clear, essential meaning. If the customer, client, or supplier does not understand the message the first time, each follow-up attempt to clarify the meaning through interaction is a cost. Table 6.1.4 presents a few examples of common bureaucratic phrases and standard English alternatives.

Repetition can be an effective strategy for reinforcing a message in oral communication, but in written communication, it adds needless length to a document and impairs clarity.

- Redundant – In this day and age air transportation by air carrier is the clear winner over alternative modes of conveyance for speed and meeting tight deadlines.

- Clear – Today air transportation is faster than other methods.

When a writer states that something is a “true fact,” a group achieved a “consensus of opinion,” or that the “final outcome” was declared, the word choices reflect an unnecessary redundancy. A fact, consensus, or outcome need not be qualified with words that state similar concepts. If it is fact, it is true. A consensus, by definition, is formed in a group of diverse opinions. An outcome is the final result, so adding the word “final” repeats the fact unnecessarily.

In business writing, we seek clear, concise writing that speaks for itself with little or no misinterpretation. The more complex a sentence becomes, the easier it is to lose track of its meaning. When we consider that it may be read by someone for whom English is a second language, the complex sentence becomes even more problematic. If we consider its translation, we add another layer of complexity that can lead to miscommunication. Finally, effective sentences follow the KISS formula for success: Keep It Simple— Simplify!

Transitions

If you were going to build a house, you would need a strong foundation. Could you put the beams to hold your roof in place without anything to keep them in place? Of course not; they would fall down right away. In the same way, the columns or beams are like the main ideas of your document. They need to have connections to each other so that they become interdependent and stay where you want them so that your house, or your writing, doesn’t come crashing down.

Transitions involve words or visual devices that help the audience follow the author’s ideas, connect the main points to each other, and see the relationships you’ve created in the information you are presenting. They are often described as bridges between ideas, thoughts, or concepts, providing some sense of where you’ve been and where you are going with your document. Transitions guide the audience in the progression from one significant idea, concept, or point to the next. They can also show the relationships between the main point and the support you are using to illustrate your point, provide examples for it, or refer to outside sources.

Key Takeaway

Organization is the key to clear writing. Organize your document using key elements, an organizing principle, and an outline. Organize your paragraphs and sentences so that your audience can understand them, and use transitions to move from one point to the next.

Exercises

What functions does an organization serve in a document? Can they be positive or negative? Explain and discuss with a classmate.

Create an outline from a sample article or document. Do you notice an organizational pattern? Explain and discuss with a classmate.

Which of the following sentences are good examples of correct and clear business English? For sentences needing improvement, describe what is wrong and write a sentence that corrects the problem. Discuss your answers with your classmates.

-

- Marlys has been chosen to receive a promotion next month.

- Because her work is exemplary.

- At such time as it becomes feasible, it is the intention of our department to facilitate a lunch meeting to congratulate Marlys

- As a result of budget allocation analysis and examination of our financial condition, it is indicated that salary compensation for Marlys can be increased to a limited degree.

- When will Marlys’s promotion be official?

- I am so envious!

- Among those receiving promotions, Marlys, Bob, Germaine, Terry, and Akiko.

- The president asked all those receiving promotions come to the meeting.

- Please attend a meeting for all employees who will be promoted next month.

- Marlys intends to use her new position to mentor employees joining the firm, which will encourage commitment and good work habits.

Find an example of a poor sentence or a spelling or grammar error that was published online or in print and share your findings with the class.

Ayres, J., & Miller, J. (1994). Effective public speaking (4th ed., p. 274). Madison, WI: Brown & Benchmark.

Beebe, S. [Steven], & Beebe, S. [Susan]. (1997). Public speaking: An audience-centered approach (3rd ed., pp. 121–122). Boston, MA: Allyn & Bacon.

Maslow, A. (1970). Motivation and personality (2nd ed.). New York, NY: Harper & Row.

Schutz, W. (1966). The interpersonal underworld. Palo Alto, CA: Science and Behavior Books.

Winans, J. A., Public Speaking (New York: Century, 1917), 407.

This page titled 6.1: Organization is shared under a CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 license and was authored, remixed, and/or curated by Anonymous (LibreTexts Staff and Kirkwood Community College), from which source content was edited to the style and standards of the Pressbook platform licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License by Brandi Schur.