Learning Objectives

Label and discuss three components of an argument.

Identify and provide examples of emotional appeals.

According to the famous satirist Jonathan Swift, “Argument is the worst sort of conversation.” You may be inclined to agree. When people argue, they are engaged in conflict, and it’s usually not pretty. It sometimes appears that way because people resort to fallacious arguments or false statements or simply do not treat each other respectfully. They get defensive, try to prove their own points and fail to listen to each other.

But this should not be what happens in a persuasive argument. Instead, when you argue in a persuasive speech, you will want to present your position with logical points, supporting each point with appropriate sources. You will want to give your audience every reason to perceive you as an ethical and trustworthy speaker. Your audience will expect you to treat them with respect and to present your argument in a way that does not make them defensive. Contribute to your credibility by building sound arguments and using strategic arguments with skill and planning.

This section will briefly discuss the classic form of an argument, a more modern interpretation, and finally, seven basic arguments you may choose to use. Imagine that each is a tool in your toolbox and that you want to know how to use each effectively. Know that people who try to persuade you, from telemarketers to politicians, usually have these tools at hand.

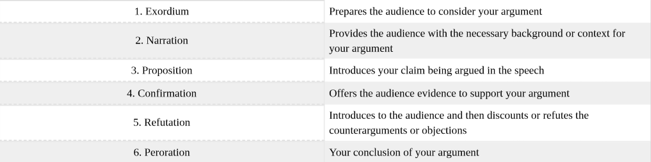

Let’s start with a classical rhetorical strategy, as shown in Table 14.5.1. It asks the rhetorician, speaker, or author to frame arguments in six steps.

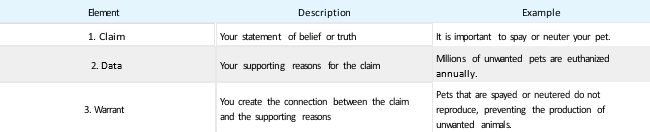

The classical rhetorical strategy is a standard pattern; you will probably see it in speech and English courses. The pattern is useful to guide you in your preparation of your speech and can serve as a valuable checklist to ensure that you are prepared. While this formal pattern has distinct advantages, you may not see it used exactly as indicated here daily. What may be more familiar to you is Stephen Toulmin’s rhetorical strategy, which focuses on three main elements, shown in Table 14.5.2.

Toulmin’s rhetorical strategy is useful because it makes the claim explicit, clearly illustrating the relationship between the claim and the data, and allows the listener to follow the speaker’s reasoning. You may have a good idea or point, but your audience will be curious and want to know how you arrived at that claim or viewpoint. The warrant often addresses the inherent and often unspoken question, “Why is this data so important to your topic?” and helps you illustrate relationships between information for your audience. This model can help you clearly articulate it for your audience.

Argumentation Strategies: GASCAP/T

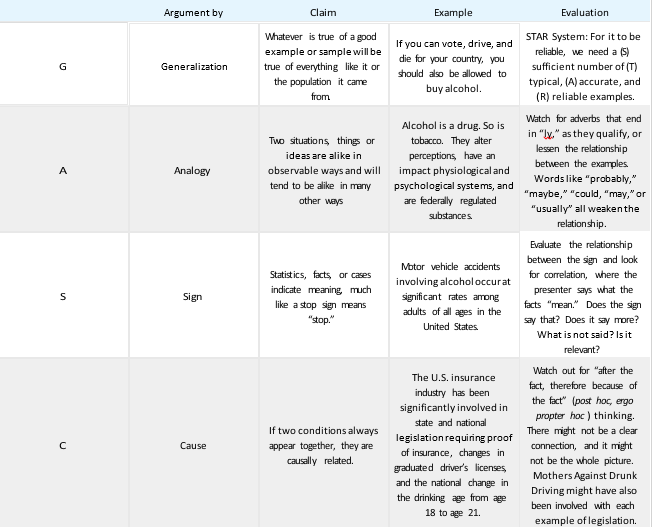

Here is a useful way of organizing and remembering seven key argumentative strategies:

- Argument by Generalization

- Argument by Analogy

- Argument by Sign

- Argument by Consequence

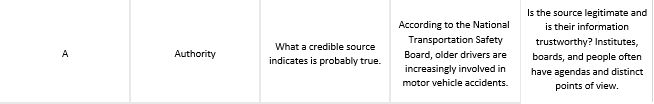

- Argument by Authority

- Argument by Principle

- Argument by Testimony

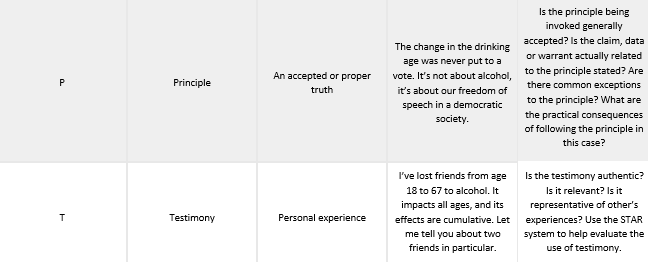

Richard Fulkerson notes that a single strategy is sufficient to make an argument sometimes, but more commonly, it is an effort to combine two or more strategies to increase your powers of persuasion. He organized the argumentative strategies in this way to compare the differences, highlight the similarities, and allow for their discussion. This model, often called by its acronym GASCAP, is a useful strategy to summarize six key arguments and is easy to remember. In Table 14.5.3, we have adapted it, adding one more argument that is often used in today’s speeches and presentations: the argument by testimony. This table presents each argument, provides a definition of the strategy and an example, and examines ways to evaluate each approach.

Evidence

Now that we’ve clearly outlined several argument strategies, how do you support your position with evidence or warrants? If your premise or the background from which you start is valid, and your claim is clear and clearly related, the audience will naturally turn their attention to “prove it.” This is where the relevance of evidence becomes particularly important. Here are three guidelines to consider in order to ensure your evidence passes the “so what?” test of relevance in relation to your claim. Make sure your evidence is:

- Supportive examples are clearly representative, accurate statistics, authoritative testimony, and reliable information.

- Relevant Examples clearly relate to the claim or topic, and you are not comparing “apples to oranges.”

- Effective Examples are clearly the best available to support the claim, quality is preferred to quantity, there are only a few well chosen statistics, facts or data.

Appealing to Emotions

While we’ve highlighted several points to consider when selecting information to support your claim, know that Aristotle strongly preferred an argument based on logic over emotion. Can the same be said for your audience, and to what degree is emotion and your appeal to it in your audience a part of modern life?

Emotions are psychological and physical reactions, such as fear or anger, to stimuli that we experience as feelings. Our feelings or emotions directly impact our own point of view and readiness to communicate, but they also influence how, why, and when we say things. Emotions influence not only how you say what you say but also how you hear and what you hear. At times, emotions can be challenging to control. Emotions will move your audience, and possibly even move you, to change or act in certain ways. Marketing experts are famous for creating a need or associating an emotion with a brand or label in order to sell it. You will speak the language of your audience in your document and may choose to appeal to emotion, but you need to consider the strategic use as a tool with two edges.

Aristotle indicated that the best and most preferable way to persuade an audience was through the use of logic, which is free of emotion. He also recognized that people are often motivated, even manipulated, by the exploitation of their emotions. In our modern context, we still engage in this debate, demanding to know the facts separate from personal opinion or agenda but see the use of emotion to sell products. If we think of the appeal to emotion as a knife, we can see it has two edges. One edge can cut your audience, and the other can cut you. If you advance an appeal to emotion in your document on spaying and neutering pets and discuss the millions of unwanted pets that are killed each year, you may elicit an emotional response. If you use this approach repeatedly, your audience may grow weary of it, and it will lose its effectiveness. If you change your topic to the use of animals in research, the same strategy may apply, but repeated attempts at engaging an emotional response may backfire on you, in essence, “cutting” you and producing a negative response called emotional resistance.

Emotional resistance involves getting tired, often to the point of rejection, of hearing messages that attempt to elicit an emotional response. Emotional appeals can wear out the audience’s capacity to receive the message. As Aristotle outlined, ethos (credibility), logos (logic), and pathos (passion, enthusiasm, and emotional response) constitute the building blocks of any document. It’s up to you to create a balanced document, where you may appeal to emotion but choose to use it judiciously.

On a related point, the use of an emotional appeal may also impair your ability to write persuasively or effectively. If you choose to present an article to persuade on the topic of suicide and start with a photo of your brother or sister that you lost to suicide, your emotional response may cloud your judgment and get in the way of your thinking. Never use a personal story or even a story of someone you do not know if the inclusion of that story causes you to lose control. While it’s important to discuss relevant topics, including suicide, you need to assess your own relationship to the message. Your documents should not be an exercise in therapy, and you will sacrifice ethos and credibility, even your effectiveness, if you “lose it” because you are really not ready to discuss the issue.

As we saw in our discussion of Altman and Taylor, most relationships form from superficial discussions and grow into more personal conversations. When planning your speech to persuade, consider these levels of self-disclosure to avoid violating conversational and relational norms.

Now that we’ve outlined emotions and their role in a speech in general and a speech to persuade specifically, it’s important to recognize the principles about emotions in communication that serve us well when speaking in public. DeVito offers us five key principles to acknowledge emotions’ role in communication and offer guidelines for their expression.

Emotions Are Universal

Emotions are a part of every conversation or interaction. Whether you consciously experience them while communicating with yourself or others, they influence how you communicate. By recognizing that emotions are a component in all communication interactions, we can emphasize understanding both the message’s content and the emotions that influence how, why, and when the content is communicated.

The context, which includes your psychological state of mind, is one of the eight basic components of communication. The expression of emotions is important, but it requires the three Ts: tact, timing, and trust. If you are upset and at risk of being less than diplomatic, or the timing is not right, or you are unsure about the level of trust, consider whether you can effectively communicate your emotions. By considering these three Ts, you can help yourself express your emotions more effectively.

Emotional Feelings and Emotional Expression Are Not the Same

Experiencing feelings and actually letting someone know you are experiencing them are two different things. We experience feeling in terms of our psychological state, or state of mind, and in terms of our physiological state, or state of our body. If we experience anxiety and apprehension before a test, we may have thoughts that correspond to our nervousness. We may also increase our pulse, perspiration, and respiration (breathing) rate. Our expression of feelings by our body influences our nonverbal communication, but we can complement, repeat, replace, mask, or even contradict our verbal messages. Remember that we can’t accurately tell what other people are feeling simply through observation, and neither can they tell what we are feeling. We need to ask clarifying questions to improve understanding. With this in mind, plan for a time to provide responses and open dialogue after the conclusion of your speech.

Emotions Are Communicated Verbally and Nonverbally

You communicate emotions not only through your choice of words but also through the manner in which you say those words. The words themselves communicate part of your message, but the nonverbal cues, including inflection, timing, space, and paralanguage, can modify or contradict your spoken message. Be aware that emotions are expressed in both ways, and pay attention to how verbal and nonverbal messages reinforce and complement each other.

Emotional Expression Can Be Good and Bad

Expressing emotions can be a healthy activity for a relationship and build trust. It can also break down trust if expression is not combined with judgment. We’re all different, and we all experience emotions, but how we express our emotions to ourselves and others can significantly impact our relationships. Expressing frustrations may help the audience realize your point of view and see things as they have never seen before. However, expressing frustrations and blaming can generate defensiveness and decrease effective listening. When you’re expressing yourself, consider the audience’s point of view, be specific about your concerns, and emphasize that your relationship with your listeners is important to you.

Emotions Are Often Contagious

Have you ever felt that being around certain people made you feel better while hanging out with others brought you down? When we interact with each other, some of our emotions can be considered contagious. If your friends decide to celebrate, you may get caught up in the energy of their enthusiasm. Thomas Joiner noted that when one college roommate was depressed, it took less than three weeks for the depression to spread to the other roommate (Joiner, T., 1994). It is important to recognize that we influence each other with our emotions, positively and negatively. Your emotions as the speaker can be contagious, so use your enthusiasm to raise the level of interest in your topic. Conversely, you may be subject to “catching” emotions from your audience. Your listeners may have just come from a large lunch and feel sleepy, or the speaker who gave a speech right before you may have addressed a serious issue like suicide. Considering the two-way contagious action of emotions means that you’ll need to attend to the emotions that are present as you prepare to address your audience.

Key Takeaway

Everyone experiences emotions, and as a persuasive speaker, you can choose how to express emotion and appeal to the audience’s emotions.

Exercises

Think of a time when you have experienced emotional resistance. Write two or three paragraphs about your experience. Share your notes with the class.

Which is the more powerful, appeal to reason or emotion? Discuss your response with an example.

Select a commercial or public service announcement that uses an emotional appeal. Using the information in this section, how would you characterize the way it persuades listeners with emotion? Is it effective in persuading you as a listener? Why or why not? Discuss your findings with your classmates.

Find an example of an appeal to emotion in the media. Review and describe it in two to three paragraphs and share it with your classmates.

Altman, I., & Taylor, D. (1973). Social penetration: The development of interpersonal relationships. New York, NY: St. Martin’s Press.

Aristotle. (1991). On rhetoric (G. A. Kennedy, Trans.). New York, NY: Oxford University Press.

DeVito, J. (2003). Messages: Building interpersonal skills. Boston, MA: Allyn & Bacon.

Fulkerson, R. (1996). The Toulmin model of argument and the teaching of composition. In B. Emmel, P. Resch, & D. Tenney (Eds.), Argument revisited: Argument redefined: Negotiating meaning the composition classroom (pp. 45–72). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Joiner, T. (1994). Contagious depression: Existence, specificity to depressed symptoms, and the role or reassurance seeking. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 67, 287.

Toulmin, S. (1958). The uses of argument. New York, NY: Cambridge University Press.

This page titled 14.5: Making an Argument is shared under a CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 license and was authored, remixed, and/or curated by Anonymous (LibreTexts Staff), from which source content was edited to the style and standards of the Pressbook platform licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License by Brandi Schur.