GOTHIC

Chapbooks and Bluebooks: A Selection

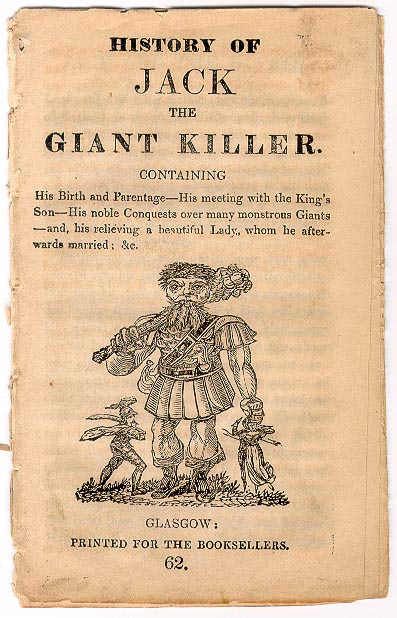

History of Jack the Giant Killer (1800)

Figure 1. A chapbook: History of Jack the Giant Killer (Glasgow, 1800), 24 pages, 15cm x 9cm. Elizabeth Nesbitt Chapbook Collection, University of Pittsburgh, Information Sciences Library, https://web.archive.org/web/20070208021828/http://www.library.pitt.edu/libraries/is/enroom/chapbooks/title.htm. Image in public domain: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Chapbook_Jack_the_Giant_Killer.jpg?uselang=en#Licensing.

“Mary, A Fragment”

A one-page story from the 1800 collection Gothic Stories

MARY.

A Fragment, from the Montlily Cabinet.

THE castle-clock struck one; the night was dark, drear, and tempestuous. Henry set in an antique chamber of it, over a wood fire, which, in the stupor of contemplation, he had suffered to decrease into a few half lifeless embers; on the table by him lay the portrait of Mary; the features of which were not very perfectly disclosed by a taper that just glimmered in the socket. He took up the portrait, however, and gazed intensely upon it, till the taper, suddenly burning brighter, discovered to him a phenomenon, he was no less terrified than surprised at. The eyes of the portrait moved; the feature, from an angelic smile, changed to a look of solemn sadness; a tear stole down each cheek, and the bosom palpitated as with sighing.

Again the clock struck one — it had struck the same hour but ten minutes before. Henry heard the castle gate grate on its hinges — it slammed too — the clock struck one again; and a deadly groan echoed through the castle. Henry was not subject to superstitious fears; neither was he a coward; yet a hero of romance might have been justified in a case like this, should he have betrayed fear. Henry’s heart sunk within him; his knees smote together, and, upon the chamber door being opened, and his name uttered in a hollow voice, he dropped the portrait to the floor; and sat, as if riveted to the chair, without daring to lift up his eyes. At length, however, as silence again prevailed, he ventured, for a moment, to raise his eyes, when — my blood freezes as I relate it — before him stood the figure of Mary in a shroud; her beamless eye fixed upon him with a vacant stare; and her bared bosom exposing a most deadly gash. “Henry! Henry! Henry!” she repeated in a hollow tone — “Henry! I am come for thee! thou hast often said that death with me was preferable to life without me; come, then, and enjoy all the ecstasies of love these ghastly features, added to the contemplation of a charnel-house, can inspire; then, grasping his hand with her icy fingers, he swooned; and instantly found himself stretched on the hearth of his master’s kitchen; a romance in his hand, and the house-dog by his side, whose cold nose touching his hand, had awakened him.[1]

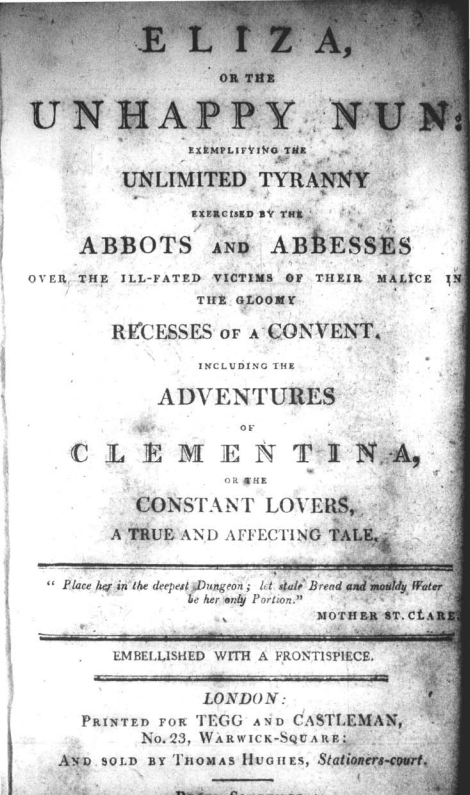

Eliza, or the Unhappy Nun, etc. (1803)

Figure 2. A Gothic bluebook: Eliza, or the Unhappy Nun, etc. (London: Tegg and Castleman, 1803). Image in public domain. Digitized by Marquette University: https://epublications.marquette.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1019&context=english_gothic.

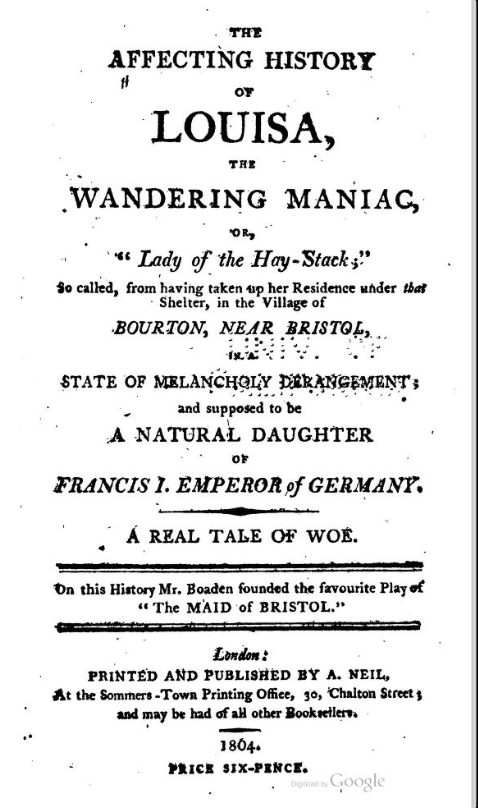

The Affecting History of Louisa, etc. (1804)

Figure 3. A Gothic bluebook: George Henry Glasse, The Affecting History of Louisa, etc. (London: A. Neil, 1804). Archive.org: https://archive.org/details/affectinghistor00boadgoog/page/n10/mode/2up. Image in public domain.

- Text in public domain. “Mary, A Fragment,” Gothic Stories. Sir Bertrand’s Adventures in a Ruinous Castle; The Story of Fitzalan; etc. (London: S. Fisher, 1800), pp. 51–52. Archive.org: https://archive.org/details/gothicstoriessir00unknuoft/mode/2up. ↵