7 Empathy and Sensitivity

Empathy

Empathy is defined as: “the action of understanding, being aware of, being sensitive to, and vicariously experiencing the feelings, thoughts, and experience of another of either the past or present without having the feelings, thoughts, and experience fully communicated in an objectively explicit manner” (Merriam-Webster, 2023).

Literature Review: Interpersonal Reactivity (Empathy)

First-year medical students were surveyed to determine personal values and levels of cognitive empathy using the Schwartz Portrait Values Questionnaire and Davis’ Interpersonal Reactivity Index. Personal values of self-transcendence correlate with well-being and the protection of people more so than power and achievement values which have a negative relationship with emotional and cognitive dimensions of empathy (Ardenghi et al., 2021). The findings included that benevolence and power took the first and last rank in relationship to empathy (Ardenghi et al., 2021). Gender differences included male students who scored significantly higher than female students on power, achievement, and hedonism. Female students demonstrated higher levels of benevolence, universalism, conformity, and tradition (Ardenghi et al., 2021). The standardized regression coefficient indicates that female students scored significantly higher on empathetic concern than did male students. Gender remained a significant predictor of empathetic concern even after having entered personal values into the regression models (Ardenghi et al., 2021). Empathetic concern increased by 26.1% (p < .001) for model 1 and 14.7% (p < .001) for model 2. Additionally, self-transcendence and self-enhancement each had a significant unique contribution to the explanation of empathetic concern and perspective taking above and beyond the effect of gender. In particular, significant findings included that self-transcendence was positively associated with both empathetic concern and perspective-taking; higher scores of self-enhancements were negatively related to both empathetic concern and perspective-taking (Ardenghi et al., 2021).

Much like nursing students, young medical students are driven by the personal values that lead to the helping professions grounded in the values of equality and altruism (Ardenghi et al., 2021). The medical students had high levels of self-direction that is linked to critical thinking and the capacity to make ethical and practical decisions in clinical settings (Ardenghi et al., 2021). The researchers’ findings and conclusions included the discussion of healthcare educators who support and foster empathy and humanitarian values in students’ early careers and can support professional behaviors and attitudes that are at the core of patient-centered care (Ardenghi et al., 2021).

Oncologist’s grief and empathy were studied by Hayuni et al., (2021) to discover if burnout and compassion fatigue were related to increased empathy in providers who experience high mortality rates such as in cancer patients. Intense emotional relationships characterized by vulnerability to personal distress and emotional exhaustion experienced by professional caregivers are a negative aspect of empathy (Hayuni et al., 2019). Conversely, empathy also has the positive aspect of empathetic concern and perspective-taking and was measured with the Davis (1980) Interpersonal Reactivity Index in the study (Hayuni et al., 2019). These participants’ average years in the field was 13.4 years, and the participants reported moderate levels of grief, high levels of perspective-taking, and relatively high levels of empathic concern, personal distress was also high (Hayuni et al., 2019).

The researchers reported that for both personal distress and perspective-taking, grief was found to be significant with standardized effect sizes of 0.32 and -0.27, the direct effects of secondary traumatic stress and burnout fully accounted for the relationship between the following two components of empathy including perspective taking was negatively correlated (the cognitive component) and personal distress was positively correlated (affective component) with grief with standard effect sizes of 0.14 and -0.15, were found to be non-significant (Hayuni et al., 2019). Furthermore, the researchers discovered that it may be possible that the cognitive component of empathy allows the caregiver to better organize and process the suffering of others whereas the affective aspect of empathy puts the provider in an immersion of the situation and the provider may lack the distance necessary to achieve empathetic concern (Hayuni et al., 2019). The findings point to empathy as a complex socio-emotional competency and that the positive emotions of warmth for instance reported by the providers was a substantial benefit of empathy and that it should be studied further (Hayuni et al., 2019).

Korkmaz Doğdu et al. (2022) compared nursing students’ levels of empathy to caring behaviors. First-year students were excluded from this study as they had not had the benefit of clinical experience at the time of the study, second, third, and fourth-year students participated. 276 students participated and were asked to complete the Empathic Tendency Scale and the Caring Assessment Questionnaire. The study revealed that students had low levels of empathy 62.71(20-100) and good caring behaviors 5.82 (1-7).

The researchers highlighted the students’ highest subscale scores of caring behaviors were in trusting relationships, monitoring, and comfort sub-dimensions. The female senior students scored higher in overall caring behaviors. In addition, students with positive professional perceptions also had higher caring behavior scores.

Furthermore, as the educational level with more experience rises, empathy and caring behaviors increase. The study also revealed that communication skills were found to have a moderate impact on caring behaviors and that communication skills serve as a foundation for caring relationships with patients (Korkmaz Doğdu et al., 2022). Regarding empathy, specifically this study has shown that empathy increased with grade level. “Students’ empathy skills are believed to improve as a result of favorable experiences they have while in undergraduate education” (Korkmaz Doğdu et al., 2022, p. 2657).

Non-academic factors also influence empathy in undergraduate nursing students. Findings presented by Berduzco-Torres et al., (2021) demonstrated that not only individual characteristics such as gender and age but also social and family environments can influence the development of empathy in nursing students. The researchers performed a cross-sectional study that included two private and one public nursing school in Peru. Demographic information, as well as the following measures, were utilized: Jefferson Scales of Empathy, Attitudes toward Physician-Nurse Collaboration, and Lifelong Learning, Emotional Loneliness Scale for Adults, and the Scale of Life Satisfaction. A multivariate regression model was utilized to further characterize the factors’ impact on the development of empathy in nursing students. In addition, targeted training in empathy was not provided to the students in the nursing education curriculum.

Positive correlations between empathy and working in teams (ρ=+0.59; p<0.001), lifelong learning (ρ=+0.39; p<0.001), and having a positive relationship with mother (ρ=+0.08; p=0.03) and negative relationships including loneliness (ρ=-0.41; p<0.001) and age (ρ=-0.15; p<0.001) were observed (Berduzco-Torres et al., 2021). Berduzco-Torres et al., (2021) point to the social environment of the campus, public vs. private plays an influencing role in nursing students’ acquisition of empathy in the absence of targeted training. Students in public schools (M=107, Mdn = 97, SD = 19.45) compared to private schools (M=99.56, Mdn = 99.50, SD = 16.55) reported higher levels of empathy (Berduzco-Torres et al., 2021). The researchers further described the impact of elitism as a social influence that propagates cultural and racial stereotypes that reduce empathic response (Berduzco-Torres et al., 2021).

Sensitivity

Literature Review: Sensitivity

Pluess et al. (2023) conducted three research studies using the HSPS (12-item) instrument that verified the scale’s validity as a self-report collection tool and revealed that high sensitivity in individuals is linked to personality trait and that it is a “distinct and quantifiable feature of human nature” (Pluess et al., 2023, p. 10). The researchers studied teacher trainees in the first year of instruction as this time in the early career is particularly challenging. The teachers high in sensitivity demonstrated a significant decline in well-being early in the study, however, demonstrated full recovery when tested at the end of the 10-month study. The teacher’s low sensitivity did not demonstrate this adverse effect on the environment. The findings suggest that “individual differences in environmental sensitivity can be measured efficiently with the HSP-12” (Pluess et al., 2023, p. 7). This finding may align with nursing students in the first year of education due to performance pressure, high levels of conscientiousness, and a propensity for stress in relationship to feeling unprepared in unfamiliar clinical situations (Ponce-Valencia et al., 2022; Redfearn et al., 2020).

The researchers also looked at the effect of positive experiences on highly sensitive individuals and were able to verify with a mood induction experiment that “more sensitive individuals are more responsive and benefited the most to a positive influence compared to less sensitive people” (Pluess et al., 2023, p. 8). Another interesting finding included that even though high sensitivity participants’ scores reflected “high neuroticism, particularly anxiety, and vulnerability” the scores also reflected “high openness, particularly imagination, artistic interests, and emotionality” (Pluess et al., 2023, p. 1).

Sensitivity in this context reflects the person’s innate ability to pick up on cues in the environment including “detailed characteristics and changes in the physical and social environment, and cognitively process such sensory input in order to react in ways that are adaptive given the specific features of the environment” (Pluess et al., 2023, p. 5). Interestingly, Ponce-Valencia et al., (2022) utilized an adapted version of the HSPS in Spanish students and included 284 nursing students of which 82 were in the first year of the program. The findings included that the group demonstrated that 34.5% of the students were considered highly sensitive in comparison to 20% of the general population. The researchers looked at students’ current life stressors such as unsatisfactory family relations and the results showed higher HSPS scores in those with family problems (Ponce-Valencia et al., 2022). Additional conclusions suggested that “HSP, processing ability, empathy, emotional response-ability, and sensitivity to subtle aspects” could be the focus of future studies (Ponce-Valencia et al., 2022). Pluess et al., (2023) also pointed to future research directions that could include “how an individual’s level and type of sensitivity is shaped by the environment and moderates specific environmental effects” and “detected associations with established personality traits” (p. 17).

Redfearn et al. (2020) looked at nurses with HSP as a predictor of high stress and burnout compared to peers with lower levels of HSP. 252 participants were included in the data analysis. The sample included RNs, PNs, and LVNs respectively, 55 were in the first year of licensed practice. Given the number of regression analyses performed in the study, the researchers considered a family-wise error and utilized a Bonferroni correction. A total of eight regression analyses were performed resulting in a more restrictive p value of .006.

Regression results revealed that SPS was a significant predictor of overall nursing stress after controlling for age, gender, years of nursing experience, and personality, R2 = .141, ∆ R2 = .033, F(9, 242) = 4.403, p = .003 indicating that for overall nursing stress, HSPs struggle more than non-HSPs. While still controlling for personality, follow-up regression analyses revealed that HSP significantly predicted inadequate preparation the most, R2 = .181, ∆ R2 = .058, F(9, 242) = 5.952, p = .000. The findings suggest that if an HSP feels inadequately prepared overall at work, he or she experiences more stress compared to non-HSPs. The second-strongest predicted dimension of burnout was workload, R2 = .329, ∆ R2 = .053, F(9, 242) = 3.258, p = .000, while death and dying were not found to be significantly predicted by SPS, R2 = .069, ∆ R2 = .006, F(9, 242) = 1.978, p = .221. The overall findings correlated stress and burnout with HSP (Redfearn et al., 2020).

In relation to burnout, HSP was found to significantly relate to all of the burnout subscales except for personal accomplishment. In examining the Big Five personality traits, a significant correlation existed between extraversion and negative emotionality scores, with r(252)= -.42, p < .001, and r(252) = .57, p < .001, respectively. In addition, HSP was significantly correlated with conscientiousness, r(252) = -.23, p < .001, and open-mindedness, r(252) = .23, p < .001 (Redfearn et al., 2020). Furthermore, the HSP significantly correlated with five out of seven stress subscales, indicating that HSPs get more stressed than non-HSPs for the most frequently reported stressors in nursing. HSP showed significance with workload, with r(252) = .27, p < .001, inadequate preparation, r(252) = .34, p < .001, with lack of staff support, r(252) = .26, p < .001, uncertainty concerning treatment, r(252) = .17, p < .01, and conflict with physicians, r(252) = .26, p < .001 (Redfearn et al., 2020).

The ratio of high SPS compared to peers with lower levels of SPS was not reported in the study findings. If the ratio of high SPS nurses was greater than the number of peers with low-level SPS the findings could be skewed as other research has shown that nursing seemed to include higher numbers of participants with HSPS (Ponce-Valencia et al., 2022). In addition, the findings in nurses with HSPS demonstrated significant correlations of professional values such as conscientiousness and open-mindedness. HSPs are also highly empathetic which has been shown to be a protective factor in healthcare professionals and the provision of quality patient-centered care (Ardenghi et al., 2021).

In a similar study, Elst et al. (2019) looked at HSP in relationship to the Job Demands Resource Model and predicted that HSP could have a modifying effect that is both a vulnerability and a personal resource factor. The final sample included 1019 employees of Belgian public and private organizations. In the final sample, 67.6% were female and 59.7% were male. The average tenure in the current position was 18.46 years (SD = 12.36). Next, the majority of the respondents (71.6%) had obtained a higher degree (Bachelor or Master), and 15.1% had a supervisory position (based on information from 1005 respondents). Furthermore, 70.3% of the respondents worked on a full-time basis (information about full-time versus part-time employment was available for 916 employees) (Elst et al., 2019). Three of the participating organizations were active in industry (n = 195; 19.1%); two in the service sector (n = 154, 15.1%); two in health care (n = 118; 11.6%); one in education (n = 191; 18.7%); and one was active in both healthcare and education (n = 361; 35.4%).

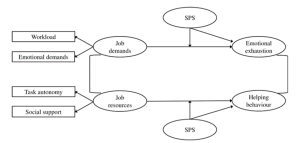

The correlations showed that all three HSP components (ease of excitation, aesthetic sensitivity, low sensory threshold) related positively to emotional exhaustion (p < .001, p < .01), and that aesthetic sensitivity (p < .001) and low sensory threshold (p < .01) were positively associated with helping behavior (Elst et al., 2019). The findings included support for HSP being added to the Job Demands Resources Model as both a personal vulnerability factor and a protective factor to demonstrate HSP’s role in the relationship between work characteristics and employee health/well-being and performance (Elst et al., 2019). Furthermore, HSP employees may react more negatively to job demands and more positively to job resources, although more overwhelmed at times with the job resources at hand can demonstrate more resilience and control to respond to challenges and environmental cues with helping behavior (Elst et al., 2019).

Figure 1. Highly Sensitive People in the Workplace. (Elst et al., 2019, p. 6).

Glossary:

Burnout: A state of emotional, physical, and mental exhaustion caused by prolonged exposure to overwhelming stressors. In the context of nursing, burnout can result from factors such as high workload, inadequate staffing, and exposure to patient suffering.

Caring Behaviors: Actions and attitudes that demonstrate concern and empathy for others. Caring behaviors are essential for building trusting relationships with patients and providing holistic, patient-centered care.

Compassion Fatigue: A state of emotional and physical exhaustion that can develop in individuals who work in helping professions and are repeatedly exposed to the trauma and suffering of others. Compassion fatigue can manifest as a reduced capacity for empathy, emotional detachment, and feelings of hopelessness.

Empathy: The capacity to understand and share the feelings of others. It involves both cognitive empathy (understanding another’s perspective) and affective empathy (experiencing emotions similar to those of another person). Empathy is a cornerstone of nursing practice, enabling nurses to connect with patients on a deeper level and provide compassionate, individualized care.

Empathic Concern: A feeling of warmth, compassion, and concern for the well-being of another person. Empathic concern motivates individuals to help others in need and is a crucial element of effective nursing care.

Highly Sensitive Person (HSP): An individual with a heightened sensitivity to sensory stimuli, emotional experiences, and environmental cues. HSPs process information more deeply and are more easily overwhelmed by intense or stimulating environments. While HSPs may experience higher levels of stress and burnout, they also tend to be more empathetic and compassionate.

Job Demands-Resources Model: This model proposes that job stress results from an imbalance between the demands of a job and the resources available to cope with those demands. According to this model, high job demands (such as heavy workload or emotional labor) can lead to stress and burnout, while adequate job resources (such as social support or autonomy) can buffer the negative effects of job demands.

Perspective-Taking: The ability to understand another person’s thoughts, feelings, and motivations from their point of view. Perspective-taking is an important aspect of empathy, as it allows individuals to see the world through the eyes of another and appreciate their unique experiences.

Personal Distress: A negative emotional response to witnessing the suffering of others. Personal distress can be a symptom of compassion fatigue and can lead to emotional exhaustion and burnout.

Secondary Traumatic Stress: Similar to compassion fatigue, secondary traumatic stress refers to the emotional and psychological distress that can result from indirect exposure to trauma, such as hearing about or witnessing the traumatic experiences of others. Healthcare professionals who work with patients who have experienced trauma are at risk for secondary traumatic stress.

Sensitivity: In the context of these sources, sensitivity refers to the heightened awareness and responsiveness of HSPs to internal and external stimuli. This sensitivity can be both a strength (enhancing empathy and perceptiveness) and a challenge (increasing vulnerability to stress and burnout).

Stress: A physiological and psychological response to challenging or threatening situations. Stress can be acute (short-term) or chronic (long-term) and can manifest in various physical, emotional, and behavioral symptoms. In nursing, stress can arise from factors such as high workload, demanding patients, and ethical dilemmas.

References:

Ardenghi, S., Rampoldi, G., Bani, M., & Strepparava, M. G. (2021). Personal values as early predictors of emotional and cognitive empathy among medical students. Current Psychology: A Journal for Diverse Perspectives on Diverse Psychological Issues. Advance online publication. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-021-01373-8

Berduzco-Torres, N., Medina, P., San-Martín, M., Delgado Bolton, R. C., & Vivanco, L. (2021). Non-academic factors influencing the development of empathy in undergraduate nursing students: a cross-sectional study. BMC Nursing, 20(1). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12912-021-00773-2

Elst, T. Vander, Sercu, M., Van den Broeck, A., Van Hoof, E., Baillien, E., & Godderis, L. (2019). Who is more susceptible to job stressors and resources? Sensory-processing sensitivity as a personal resource and vulnerability factor. PLoS ONE, 14(11). https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0225103

Empathy. 2023. In Merriam-Webster.com. Retrieved May 8, 2023, from https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/empathy

Korkmaz Doğdu, A., Aktaş, K., Dursun Ergezen, F., Bozkurt, S. A., Ergezen, Y., & Kol, E. The empathy level and caring behaviors perceptions of nursing students: A cross-sectional and correlational study. Perspect Psychiatr Care, 2022; 58: 2653–2663. https://doi.org/10.1111/ppc.13106

Hayuni, G., Hasson-Ohayon, I., Goldzweig, G., Bar Sela, G., & Braun, M. (2019). Between empathy and grief: The mediating effect of compassion fatigue among oncologists. Psycho-Oncology, 28(12), 2344–2350. https://doi.org/10.1002/pon.5227

Pluess, M., Lionetti, F., Aron, E., & Aron, A. (2023). People Differ in their Sensitivity to the Environment: An Integrated Theory, Measurement and Empirical Evidence. Journal of Research in Personality. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jrp.2023.104377

Ponce-Valencia, A., Jiménez-Rodríguez, D., Simonelli-Muñoz, A. J., Gallego-Gómez, J. I., Castro-Luna, G., & Pérez, P. E. (2022). Adaptation of the Highly Sensitive Person Scale (HSP) and Psychometric Properties of Reduced Versions of the Highly Sensitive Person Scale (R-HSP Scale) in Spanish Nursing Students. Healthcare 2022, Vol. 10, Page 932, 10(5), 932. https://doi.org/10.3390/HEALTHCARE10050932

Redfearn, R. A., van Ittersum, K. W., & Stenmark, C. K. (2020). The impact of sensory processing sensitivity on stress and burnout in nurses. International Journal of Stress Management, 27(4), 370–379. https://doi.org/10.1037/str0000158